Platform News Dumbs Mediocrity Down

A new deal between Facebook and Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp in Australia will help determine the future of what’s inside your head

It’s been a strange thing to work in the media over the past several years. Writing for a living is at peak precariousness, an experience which is similar, I imagine, to what it would be like to live in a necrotic house where every few weeks another big thing breaks, and there’s nothing anyone can do to fix it. We walk around the rooms, pointing out the terrific accumulation of minor degradation—paint cracks, loose nails—and then not infrequently we notice more serious problems, like that ominous stain which, left unattended, becomes a bathtub falling through the ceiling. None of us owns this house, we couldn’t afford it, which does not diminish our resentment about showering in the dining room. And though there is in fact an owner, which is to say someone who could fix it, it is in their best interest, oddly enough, to let it slowly fall to pieces.

It’s undisputed that Facebook/Instagram, Google/YouTube, and Twitter have made tens of thousands of times more money selling advertisements than the suckers cranking out content on their decrepit couches and wondering if that sound in the walls behind them might be rats. Facebook earns 98% of its $86 billion annual revenue from advertising that would have once gone to fund actual newspapers and magazines. For Google, $146 billion of its $182 billion in revenue poured in from ad sales. That’s a lot of money—especially considering that the amount of money that the platforms invest in producing the content they advertise against is zero.

With approximately 1 in 3 Americans now getting their news directly from Facebook, 1 in 4 from YouTube, and 1 in 6 from Twitter, the platforms are the main arbiters of the product that Americans consume under the label of news. Platform News and other media is designed for maximum likability, a product that is manufactured in bulk with cheap labor. As simple, high-fructose factory fare, divisive and emotionally partisan, it goes down quickly like a cheap sugar rush, and with that addictive mouth feel of junk food, all the better to trap consumers on the platforms. The more time you spend gobbling it up, commenting, sharing, and screaming, the more time the platforms have to convert you into advertising and data revenue.

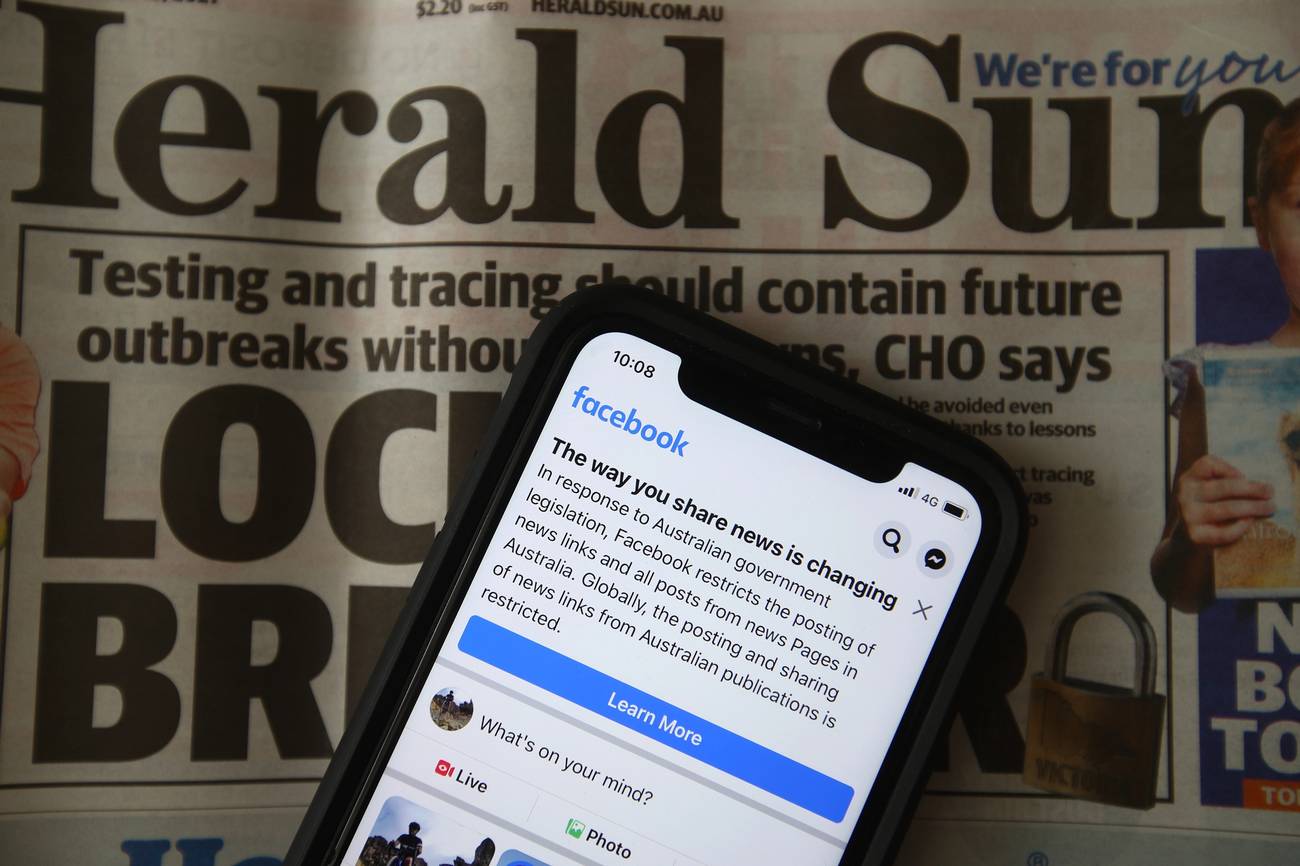

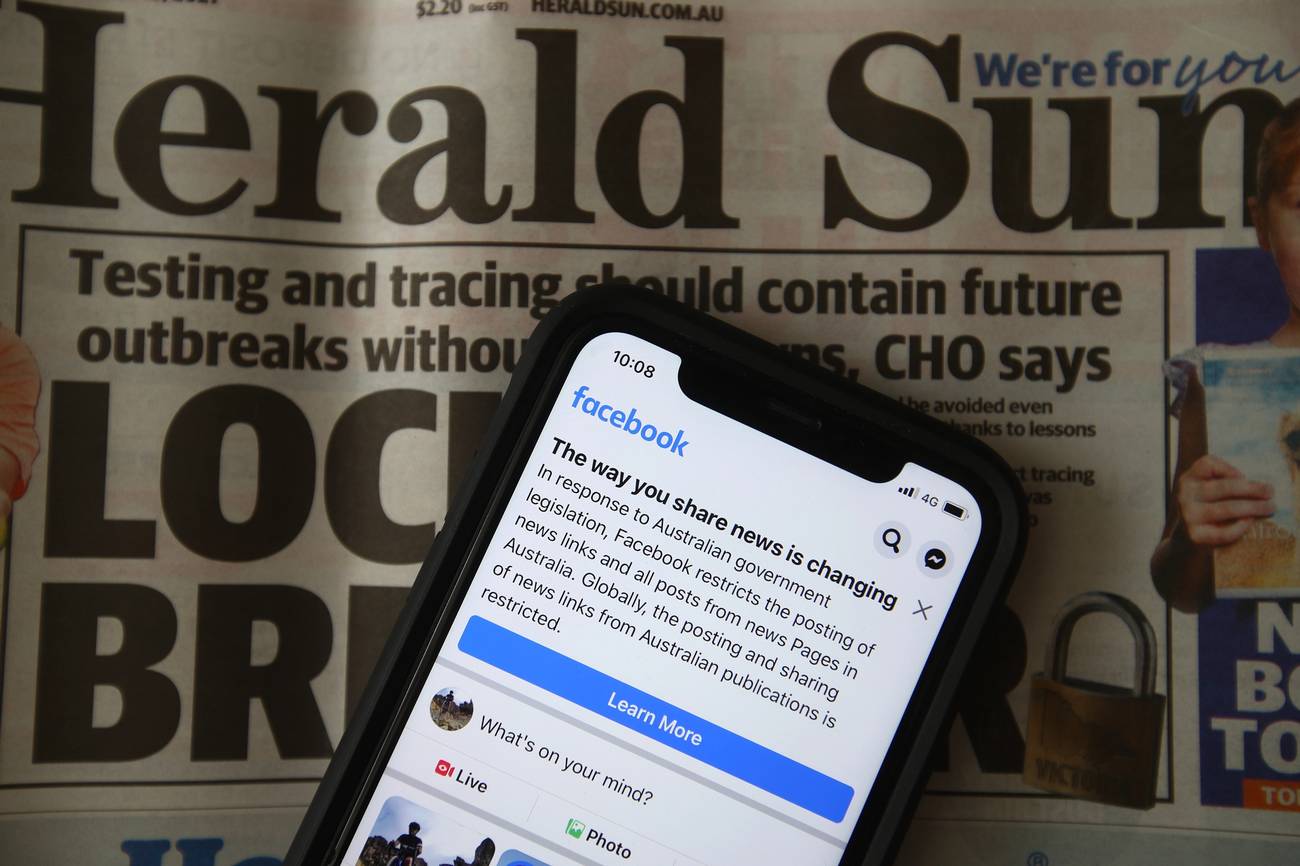

The evidence of the inevitable future of Platform News is all around us—and has been for a while now. Just look to what’s happened in the conflict of the tech platforms with the Australian government. On Dec. 9, 2020, Australian legislators introduced an unprecedented bill called the News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code which would have forced the platforms to pay licensing fees to the publishers and media creators whose content they distribute (and monetize) on their platforms. A simple bit of fairness, that might allow struggling “content providers”—who lacked any semblance of collective bargaining power against the tech monoliths—to provide content, without starving to death.

Under the terms of the bill, platforms were directed to negotiate revenue sharing terms with publishers. If a deal could not be reached, platforms and publishers would go into arbitration, where a third party would choose between one of the final offers both sides were required to present. Legislators were trying “to succeed where others have failed,” Australia’s Treasurer Josh Frydenberg said of the effort.

Google and Facebook will continue to groom exactly the kind of publishers they want and need—the creators of Platform News.

The platforms’ response was reflective of the danger that Australia’s Mandatory Bargaining bill posed to their core business model: Facebook and Google both threatened legislators that they would shut down their services in Australia if the bill became law. Contentious negotiations followed, and while Google blinked Facebook did not. As was widely reported, Facebook turned off news sharing in Australia for five days, which inadvertently or not knocked out myriad charities and essential services organizations who depend on Facebook to communicate with citizens. As intended, traffic to Australian news publishers cratered by more than 20%.

All along, Facebook has argued they don’t take business away from media companies. Rather, they give them traffic. In this way they’re simply a pointer—an often-cited reference by tech platform advocates to a 2007 9th Circuit decision in a lawsuit between Google and a pornography publisher in which the court ruled in Google’s favor, rejected the idea that Google’s use of images scraped from a porn website amounted to using the pictures without paying for them. The court found Google wasn’t stealing porn, but rather pointing at it so that others could find it.

The 9th Circuit decision accelerated the abuse of media companies by all platforms, with Google moving from a purely text-based search listing to one that pulled out extensive copy and images at the top of search pages. The more sophisticated the Google search results page became, with more copy, images, maps, and stats, the less likely the viewer was going to click through to the publisher’s website from which that information originated. Over the next six years, Google tripled their revenue.

Since then, U.S. legislators have stood idly by as the tech platforms have grown into unregulated monopolies where intense engagement increasingly takes place alongside advertisements sold by the platforms—next to headlines that only a small minority of readers bother to connect to actual articles, which in most cases no longer recognizably reflect traditional news values of objectivity, fairness, and independent reporting. The hands-off approach of American legislators and courts has been impelled in part by a lack of understanding of underlying technologies and of the speed of the cultural shifts they have engendered—a confusion which in turn is no doubt aided by the $500 million big tech spent lobbying Congress over the past 10 years.

But such a deal with the devil has its consequences. Since the advent of the printing press, written expression had been distributed under the auspices of government oversight and, to a lesser extent because of our First Amendment protections, public opinion. Free speech, media, and publications circulated through the body politic insofar as they stayed within the confines of American libel laws and copyright. Tech platforms obliterated this paradigm.

Aided by the strength of their lobbying and the immunity to traditional libel and copyright laws, as conferred by Section 230 of the notorious Communications Decency Act, the platforms could simply take what they want and publish whatever they like, with no liability. In fact, their special status as “internet service providers” would arguably have been endangered if the platforms had independently subsidized news, thus becoming “publishers” under the law—a distinction that the aggressive content moderation efforts of recent years have clearly avoided. Under the circumstances, one can argue persuasively that a significant portion of America’s decrepit institutional media now works directly for the tech platforms—given that their salaries and benefits, should they be lucky enough to have them, are subsidized by organizations which hope to offset staffing costs from whatever traffic and audience the platforms are willing to cede.

The Australian law, which comes on the heels of similar if less potent legislation in Europe, is the first significant attempt to challenge the big tech hegemony over who controls the gates and levers that circulate media, along with ideas, in the realm of the digitized global public. Some poorly informed commentators have criticized the legislation on the grounds that it hurts some fundamental principle of an imaginary open web utopia. In fact, the legislation addresses the monetization of linking, not the link itself. “Nobody claims laws banning links to a phishing page make the web unworkable, because we all recognize it’s the fraud that’s being regulated, not the linking,” James Slezak wrote in Wired.

More to the point, those suffering despite or even because of this new brand of legislation remain those working in the media itself, the rank-and-file writers, editors, photographers, and video makers who are unlikely to see any material benefit from these laws, and little improvement to the destabilization of the entire industry.

Not that there aren’t any winners here. For those in big tech who compete in some fashion against the tech platform parent companies, the potential legislation against their core advertising business model is a rare and welcome opportunity. Last month, Microsoft aligned itself with a group of European press and media organizations that will seek to integrate a version of the Australian arbitration model into the evolving EU legislative policy on tech platforms and content copyright.

The fight over the EU legislation spilled over into France, which was the first to implement the new union regulations. Google quickly threatened to pull its service out of the country, before cutting deals directly with select publishers in January, paying them for the news they used on search pages along with newly created Google news offerings tailored around publisher content. To what extent that shared revenue would go directly to major corporate media conglomerates rather than small publishers, or independent media creators, remains a question for those the new regulation is intended to protect.

In February in Pakistan, regulators crafting legislation on internet controls met the newly formed Asia Internet Coalition, a hastily assembled shakedown cohort which included the major tech platforms, saying they were going to shut off their services if regulators didn’t shape up. “The rules as currently written would make it extremely difficult for AIC Members to make their services available to Pakistani users and businesses,” they wrote with unsubtle menace.

In Australia, Google has managed, for now, to wiggle out of the legislature’s grip by cutting a three-year deal with Murdoch’s News Corp, agreeing to an undisclosed sum of some tens of millions of dollars, which is to say a fraction of a fraction of a percent of Google’s annual revenues, in exchange for a license on the publisher’s content for their platforms as well as a new product called Google News Showcase, which will surely attract no sizable audience while serving as a slick decorative exhibit of evidence that Google supports Australian media. Certainly, News Corp will profit from the deal, but none of that money is going into the hands of Australia’s independent publications.

“For small publishers who fail to make side deals with the tech giants, they could be locked out, further entrenching the narrow ownership base of the Australian media market,” said Marcus Strom, the head of a media union in Australia. “It shouldn’t be up to Facebook and Google to cherry pick and groom publishers it deems acceptable for side deals.”

And yet, of course Google and Facebook will continue to groom exactly the kind of publishers they want and need—the creators of Platform News. Are you an investigative news organization which might scrutinize Facebook’s business practices? Do you wonder if your hostility toward Facebook might factor into how Facebook, which is allowed to negotiate the terms as they see fit, decides to treat you at the negotiating table?

“We have come to an agreement that will allow us to support the publishers we choose to,” a Facebook representative said. “Going forward, the government has clarified we will retain the ability to decide if news appears on Facebook so that we won’t automatically be subject to a forced negotiation.”

Welcome to the age of Platform News.

Sean Patrick Cooper is a journalist who has contributed narrative features and essays to The New Republic, n+1, Bloomberg Businessweek, and elsewhere. His first book, The Shooter at Midnight: Murder, Corruption, and a Farming Town Divided will be published in April 2024 by Penguin.