A Producerist Manifesto

Growth is the problem. The solution is producerism, the hidden American philosophy.

Just before calling for the breakup of the United States, my spouse and I watched the new documentary Planet of the Humans. Over and over, the film exposes the bait and switch that is so-called “green” technology. None of the big multinational companies—like Apple or Tesla—who claim to operate completely by “100% renewable energy” actually do. They’re all still tapped into fossil-fuel-powered grids as much as anyone. Worse, “biomass” energy basically involves clear-cutting forests to power a few university students’ smartphones and laptops. Solar panels are made out of coal and a toxic mishmash of other dangerous and unnatural substances. Wind turbines are composed of nearly impossible to recycle fiberglass.

Outlets like Vox have called the Planet of the Humans’ message “a gift to big oil.” But the facts are that green tech destroys the natural environment every bit as much as fossil fuel does—just in different ways. Teslas. Electric cars. “Green tech.” They’re all make-believe solutions—a vainglorious Silicon Valley–spun fantasy that promises we can go on living in the hyperconsumptive, power-devouring, technological way we currently do. So now what?

The coronavirus pandemic has created a temporary reprieve from the mania of economic growth. The result has aptly illustrated that animal and plant life will recover—if only humans get out of their way. What we call “climate change” is not even a case of the sniffles in the life span of a planet that eliminated the dinosaurs 66 million years ago.

“Infinite growth on a finite planet is suicide,” Jeff Gibbs, whose thought is central to Planet of the Humans, is fond of saying. He’s right. Growth-oriented economics is indeed our central problem, but the difficulties of solving that problem are far bigger—and cut closer to the heart of our entire philosophy of life—than Gibbs or producer Michael Moore realize. In order to move away from a growth-oriented economy, as they call for, we’ll need just two small things: an entirely new political philosophy and system of political economy to match it. Heartwarming viral videos about the “great realization of 2020” won’t amount to anything without them.

Like so many in an American left that long ago stopped studying political thought and intellectual history, Moore and Gibbs fail to adequately understand what liberal political economy is—and, what alternatives to it actually endure. Here is a list of the only systems of political economy that have existed thus far.

Anarchism, syndicalism, and anarcho-syndicalism remain total vagaries, if not absolute pipe dreams. So is socialism as conceptualized by Marx. No country or even small locality has ever come anywhere close to actualizing a socialist system of economics based solely upon “labor,” which Marx designated as the first stage of his “scientific” path for history. Seeking to remove class and create a hyperefficient economic state where man will “hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, and criticize after dinner,” as Marx wished—and many on the left still dream of—is a mirage and a dangerous one.

Seeking “efficiency” over human achievement is the central mistake that got us into this mess to begin with. Efficiency is the language of the machine, a dogged pursuit of it degrades the gift that is earthy existence. Social democracy—what Americans wrongly call “socialism” or now stupidly call “democratic socialism” (because of Bernie)—is just a different, more statist form of liberalism which is still entirely dependent on growth and requires a highly efficient, effective, and noncorrupt state bureaucracy most countries do not possess, and probably are not capable of possessing—including the United States of America.

Western European-style social democracy may be the greatest form of mass governance humanity has come up with thus far. But social democracy doesn’t solve liberalism’s growth-oriented economic model, either. Without growth, no existing form of liberal economy can function. And, without liberal economics no one has yet discovered a way to provide the niceties of free expression, free speech, free association, or anything approaching the entrepreneurism of free business enterprise—all of which we might want to hold onto, whether the planet is coming down around us or not.

There is one other system of political economy I left off the earlier list—illiberal, authoritarian capitalism as currently exists in the so-called People’s Republic of China. Over the last 40 years, in total defiance of Thomas Friedman’s confident predictions, China has managed to create a powerhouse system of capitalism without a smidgen of political liberalism. Its ruling party isn’t trending that way either.

China is a totalitarian state, but with all the social inequities and cultural excesses of market capitalism. They’ve successfully mixed Brave New World with Nineteen Eighty-Four. It’s a stunning achievement really. Who knew you could mix dystopias!

In earnest, America needs to find a way to do the reverse of China—build a system of liberalism, but without capitalism. The good news is such a political movement exists in nascent form, hidden in the annals of American history.

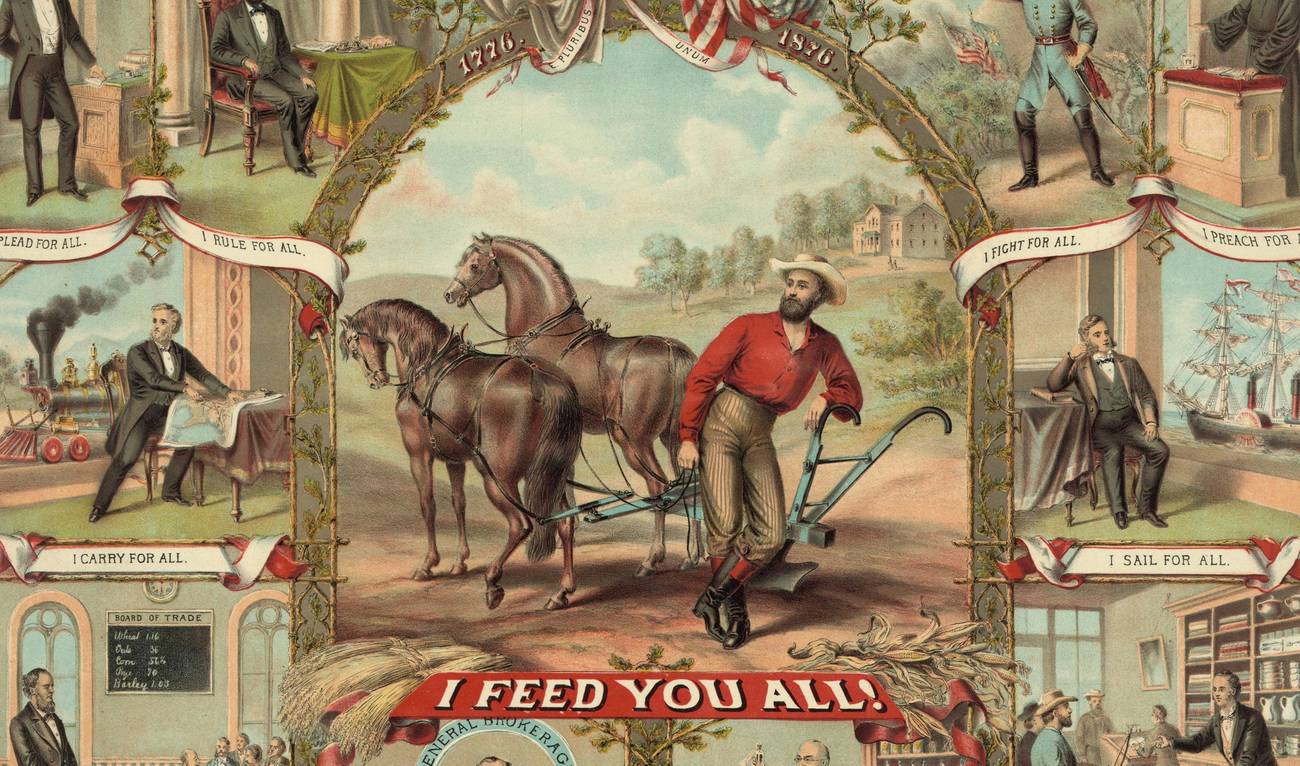

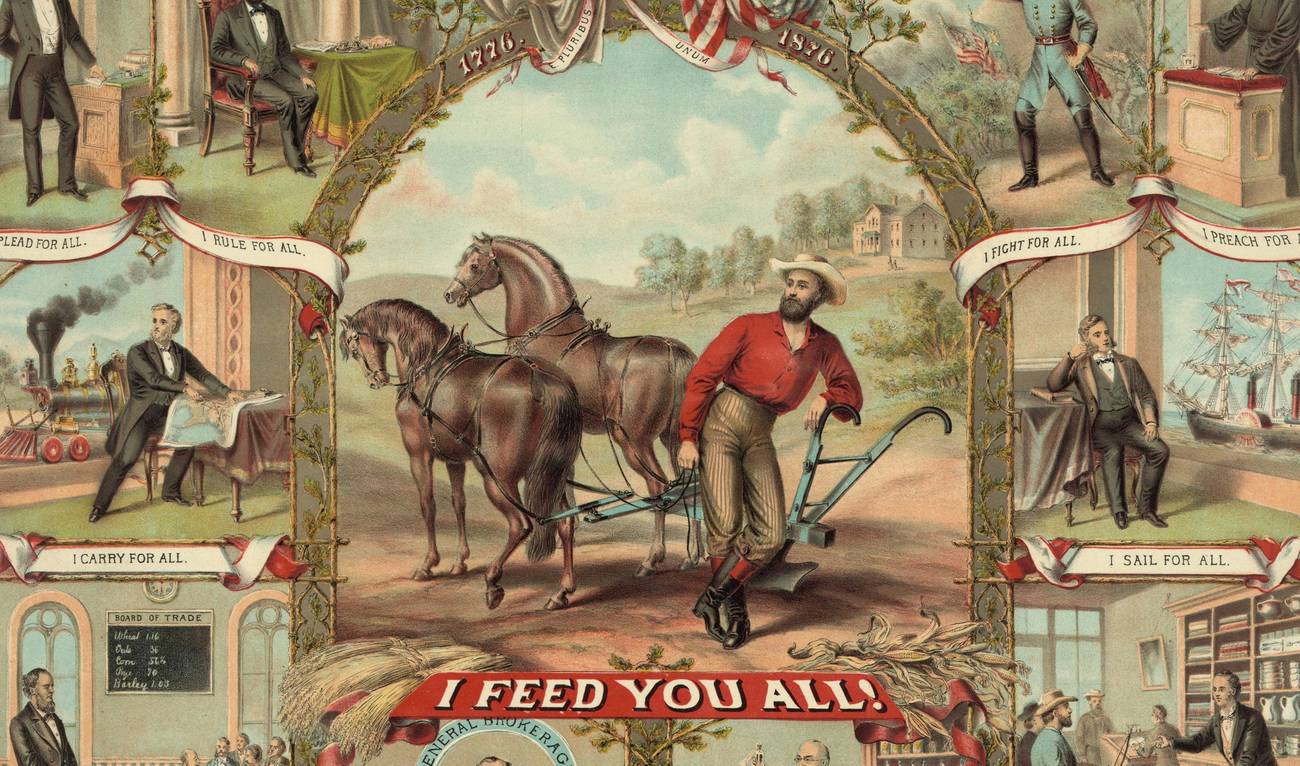

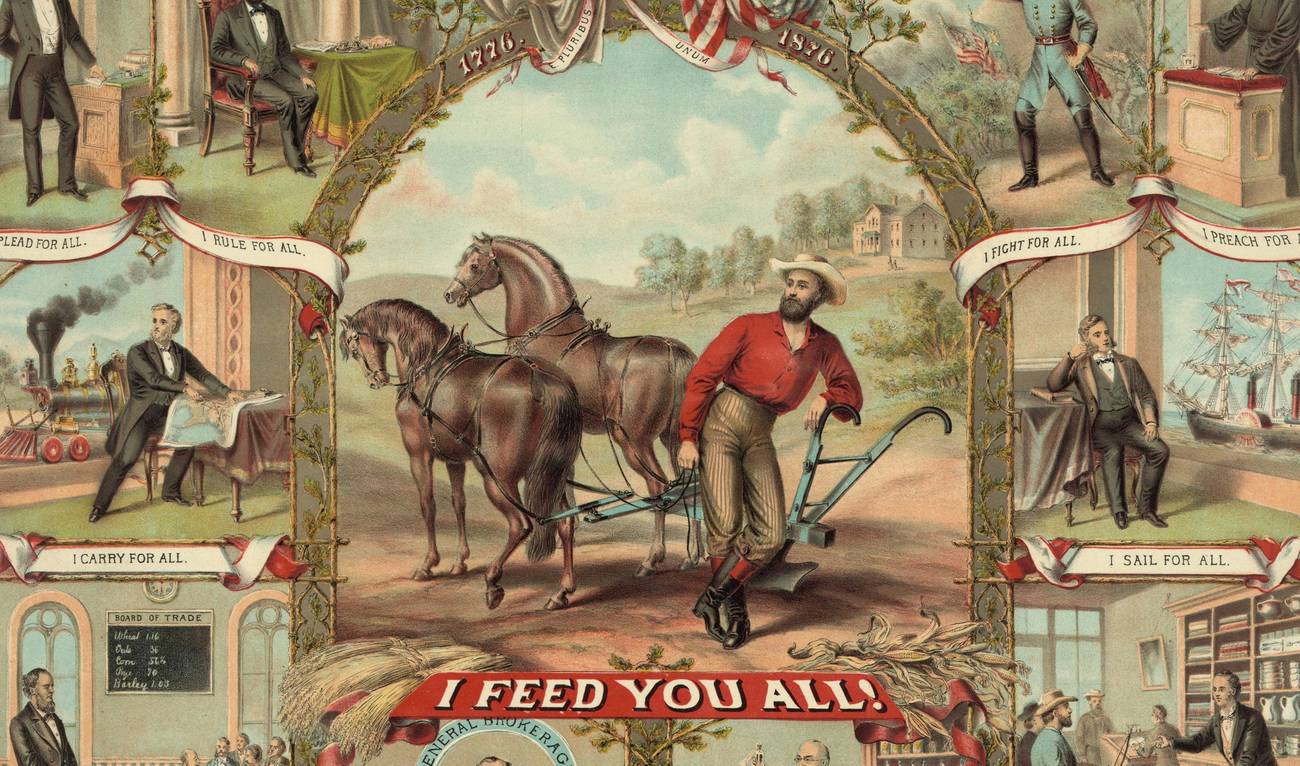

Producerism. It was a 19th-century political persuasion distinct from liberalism, socialism, communism, anarchism, fascism, feudalism, and anything else we’ve seen thus far. More than likely, you’ve never heard anything about it and there are good reasons for that.

Like the mid-to-late-19th-century American populist tradition it grew out of, producerism exhibited a total contempt for elites—both economic and cultural. This disdain for elites of all stripes endears it greatly to my punk-rock self but few others in academe or the middlebrow legacy media—two cottage industries powered by self-satisfied and hopelessly dated contempt for Middle America and the “booboisie.”

Commentators have lumped producerism in with Ludditism, Trumpism, and other ideas they label absurd on their face. But producerism suffered a far crueler fate by historians. Starting in 1900, its ideas were ignored, if not buried alive, at the peak of what could have been their moment of ascent—the gnosticism of political thought.

Before dying of lung cancer in 1994, the prescient intellectual historian Christopher Lasch spent more time than anyone before (or since) subtly singing producerism’s praises. In his last two major works, Lasch frequently pointed to the intrigue of the not-quite-liberal, not-quite-socialist, but uniquely radical (and also somehow conservative) thinking of 19th-century producerists.

On a deep level, producerism challenged the fundamentals of the Enlightenment itself. It recognized human potential, but focused its attention not on how to create unbounded freedom (as liberals and socialists do in their various ways). Instead, producerists put their attention on the inherent value—and psychological fulfillment—brought by work, craftsmanship, reasonable limits on commerce, and local governance.

Producerism never had a great frontman (or woman), philosopher, or treatise. If anything, it was more a loose dispensation than a system of thought. But, producerism deserves your attention. By summoning its values and ideas, what was old can become new, and a solution to the growth-oriented system of liberal economics can be born.

Sadly, Christopher Lasch never developed producerism into an economic system, much less a proposal or manifesto. But it is possible to fill in where Lasch left off, utilizing ideas from similar thinkers like Jacque Ellul, William Morris, Lewis Mumford, and Thorstein Veblen.

Here’s what a producerist political economy could look like:

1) In recognizing all wealth derives from its producers—not from bureaucrats, bean-counting bankers, nor CEOs or middle management—producerism bans all wage labor that does not include a substantial stake in the private enterprise’s profits, governance, and leadership. In Germany, by law, labor unions have a presence on all corporate leadership boards. This is a start, but not enough. Wealth should be controlled not by those who “manage” it, but who produce it. A nation of “hirelings,” as one of the original 19th-century producerists argued, can never truly be free.

2) Embrace the principle that all politics are local and all governance should be as well. Good governance cannot be conducted at 10,000 feet. It must be done by local leaders speaking the local language embodying local values and accepting the results—whatever they may be. If a breakup of the United States—or other large nationalities—is needed to achieve this end, so be it.

3) In embracing a localist economy and the empowerment that automatically flows from localist control, governance, and leadership, absentee ownership of businesses must be banned outright. Private enterprise, please. But no multinational corporations. No CEOs or middle management in distant states or nations. No “stockholders” who don’t work in the company. Along with this, end the legal lie of corporate personhood. Ban all business incorporations larger than 200 people. Yes, this will hamper the efficiency of mass production. But, as William Morris—the great English artisan, writer, and philosopher—argued, a truly humane society prioritizes craftsmanship and humane production not “efficiency” or economies of scale. Efficiency is the language of the machine, not the human—humanity must prioritize art and craft.

4) Replace consumption and wealth accumulation with craftsmanship and artistry as the center of the new producerist culture. Humanity must realize that healthy community and purposeful, craft-oriented and artisanal work—not consumption and fame-seeking—are the factors most likely to lead to contentment and human fulfillment.

In this vein, initiate award programs for craftsmanship and artistic recognition in every sector of the economy. Social recognition motivates most people more than wealth accumulation, which often serves as an empty surrogate for the recognition most truly seek. Provide tangible aims of human greatness and mastery that every industry, craft, and artistic endeavor can strive for. These awards should also provide substantial—but not excessive—financial considerations to those who achieve mastery of their craft or art.

5) Ban profits from “day trading” and financial speculation. One should not be able to extract value from the economy by buying stocks one day and trading them the next for a profit because their utility value changed in the interim. Restore all wealth to the productive members of the economy.

6) End liberal utility-based pricing of goods and services. In its place, launch a currency and pricing structure based upon hours worked—whatever fraction thereof involved in producing said good—with accurate mathematical calculations included for the education and training involved in various trades, including on the individual level. For example, completely untrained (entirely no skill whatsoever) work would equal one hour. Whereas, a medical doctor, Ph.D., or master craftsman’s hour of work equals whatever training, apprenticeships, and education were involved in achieving the mastery of their specific craft. Along with this principle, pay people based upon their “hours” worked (tailored according to the rough formula described here).

7) Thoroughly tax all trade transport based on mileage traveled from origin to final destination. No more making sneakers and garments in Taiwan or Saipan and shipping them back to the United States, Europe, or anywhere else to save money on labor. This restriction is intended to promote, encourage, and also protect local businesses from the “race to the bottom” of sweatshop and low-standard, overworked, overseas labor—the slave trade of our era. This restriction also protects our natural habitat from unnecessary carbon emissions and their inherently climate-altering effects. The tax from this fund will be used to provide health care, unemployment protection, and social security–like benefits to the disabled, elderly, and indigent.

8) Ban all private (or state) profits from compounded interest. Loans, credit cards, and other forms of consumer usury should be maintained, but with simple interest only. Along with this, all donations from banking operations to political candidates or elected officials should also be banned.

9) To limit the power the rentier class has over the poor and middle classes, greatly limit the number—and value—of residential real estate holdings any one person or corporate entity can legally own for purposes of residency. Anything more than say five homes should be banned to spread wealth around and limit the power and influence of unproductive work.

10) In order to encourage both the race-fetishizing “identitarian” left and the racist and xenophobic right to return to notions of broad human commonality, end all 19th-century “racial pentagon”-style—i.e., “white,” “black,” “Asian,” “indigenous,” and “Hispanic”—tracking for means of employment, higher education admissions, and even census demographics. For the census, replace race categories with national-origin tracking only. Spread opportunity around to those truly under-advantaged, no matter their skin color or national origin.

11) Encourage, sponsor, and rigorously develop the use of analog technologies to replace digital technologies whenever and wherever possible. There are inherent, natural reasons why a vinyl record sounds “warm,” “alive,” and “present.” Whereas, even a “lossless” digital audio file sounds distant, stale, and forced. There is something inherently displeasing and unhealthy—and also addictive—to the human brain about digital technologies. Our brains need to be permitted to pause and contemplate. Filling them with meaningless chatter and manipulation undermines a healthy democratic culture. Make quiet and calm a right, the way access to sunshine was a right in Rome.

The current “race riots” are only the beginning. The aftereffects of the pandemic will inevitably unleash an outburst of anti-globalist, populist wrath like nothing anyone has ever seen. Due to our physically unhealthy populous and commitment to laissez faire anti-interventionist liberalism, America will be hit harder than practically anywhere else. An Age of Contraction is surely coming. A new form of localist economy and governance must emerge from the wreckage.

After this pandemic, many will push to make face-to-face interaction a thing of the past entirely. There is no genuine community in “social media” and the constantly updated high school yearbook culture it represents. All the design methods and practices used to spur addiction to “smartphone” apps must be banned. For children, smartphones should be reclassified as a controlled substance.

Right now, digital technology controls us rather than the other way around. As D. Boon, the jolly frontman of the seminal 1980s punk band presciently sang: “When reality turns digital, I’ll vote for life in the big choice bowl. ... I’ll be glad I did.”

The pandemic-induced hiatus of the growth-oriented model has aptly illustrated that humanity can indeed function without growth, but can liberalism? Humanity and its various societies are not amateur models that can be rearranged like a child’s toy set. Class distinctions will never “disappear,” nor will class power completely disperse—no matter the future social or political arrangement. Class can only be limited, not removed.

Similarly, liberals must acknowledge another reality. Corporations are not people. Their lobbying is not “speech.” Political power will never lose its “political character.” Any assumptions to the contrary are a different brand of utopian folly—just as is assuming vested business and governmental interests will not work to pervert democratic processes in their favor.

Producerists seek to return humanity to a smaller, better—craft-oriented, localized state. But, they should not glorify, much less glamorize, “the people.” One cannot depend on the poor and working classes to “rise” and heroically demand—much less enact by unproductive violence—changes upon the cultural overclass and uber-wealthy international, “cosmopolitan” elites.

If producerism were to become a transformative movement, it would need to resist the self-infatuation of identity politics and the proletarian hallucinations of Marxism. The real struggle is always to achieve a level of commonality that resists the contorted bifocals of universality and tribal superiority. To come anywhere close to realizing the localism of the producerist vision, future advocates must persuade a substantive number in the billionaire overclass—and the professional-managerial class that serves them—that localism is the better way for everyone, including them.

In embracing the primacy of craftsmanship and artisanal work, producerists call for a new vigorous way of life that melds the best of the present with the best of the past. Producerists must build a coalition of elites and commoners that seek to build a future beyond left and right, a society local but not provincial, a culture creative but not overwrought—a new form of liberty without license built on a disposition radical in persuasion but conservative in temperament—forever limited in scope, and intent.

In order for the political economy of liberalism to survive alongside humanity, harmonious living must replace the tireless pursuit of technological and social “progress”—and the chimera of salvation they represent. Producerists must unite in demanding that distraction-free, life-fulfilling work—and quality of life—replace utility maximization in pursuit of a society that provides liberalism without capitalism.

B. Duncan Moench is Tablet’s social critic at large, a Research Fellow at Heterodox Academy’s Segal Center for Academic Pluralism, and a contributing writer at County Highway.