In America today, there is a small group of privileged citizens who wield disproportionate power over the rest of the country and seek to bend national policies to suit their collective will. Bound together by clannish, somewhat secretive ritual practices, and disproportionately represented among the nation’s wealthy and its political class, this population uses its largess and extensive influence to mold America to its perfidious ends. Their ultimate aim is to take over the United States.

I am talking, of course, about Mormons.

This isn’t my argument. It’s one that has been appearing in reputable media outlets ranging from the New York Times to Salon over the past several months as the GOP primary season has heated up. Writing in the Times about the potential presidency of Mormon Republican candidate Mitt Romney, the renowned Yale literary critic Harold Bloom darkly mused that “we are condemned to remain a plutocracy and oligarchy. I can be forgiven for dreading a further strengthening of theocracy in that powerful brew.” At Salon, a lengthy essay by journalist Sally Denton argued that “the office of the American presidency is the ultimate ecclesiastical position to which a Mormon leader might aspire,” and that in running for president, Romney sought to fulfill an LDS prophecy and usher in a Mormon “theodemocracy.” The piece quickly went viral, racking up over 1,000 Facebook shares.

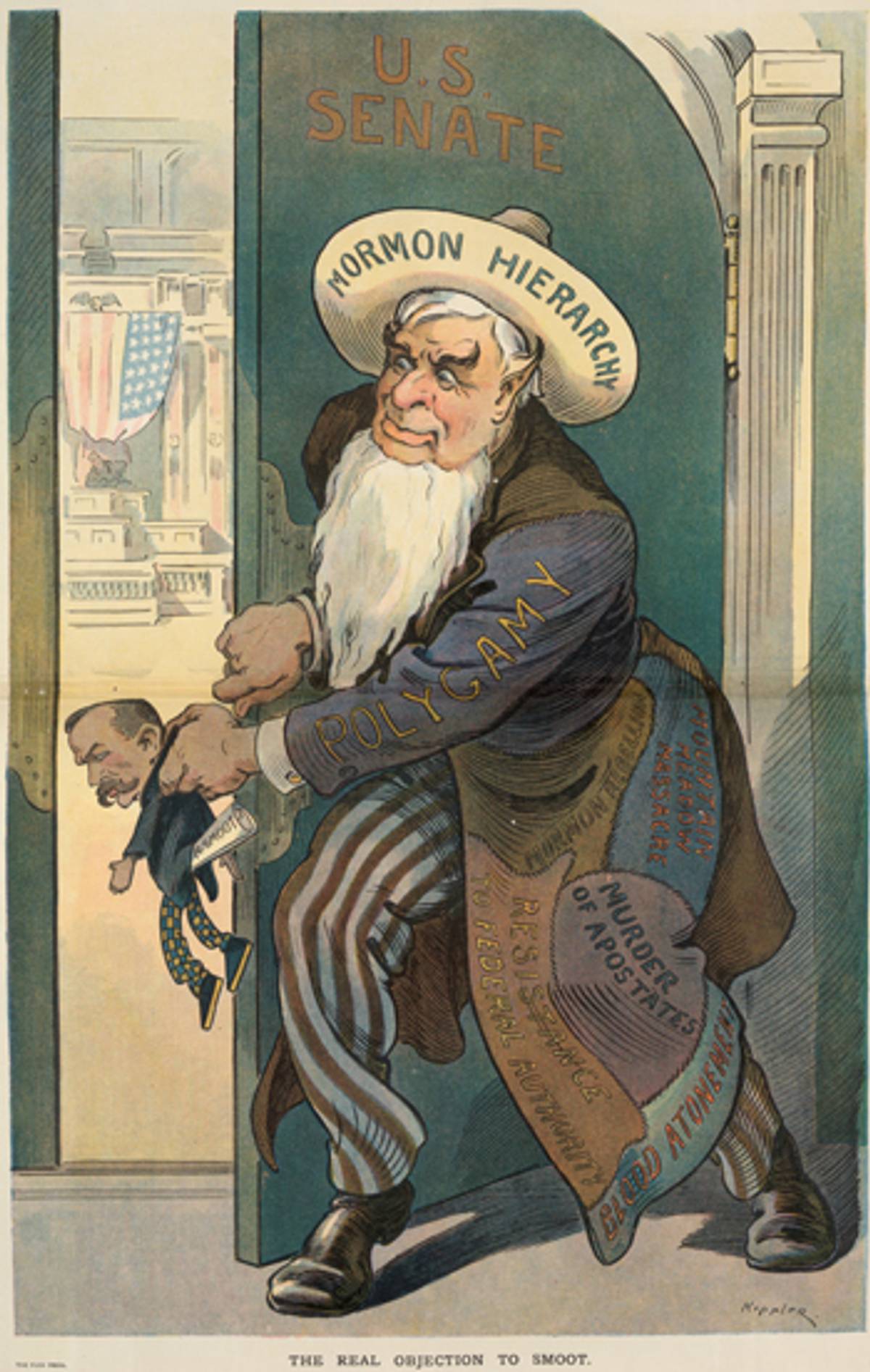

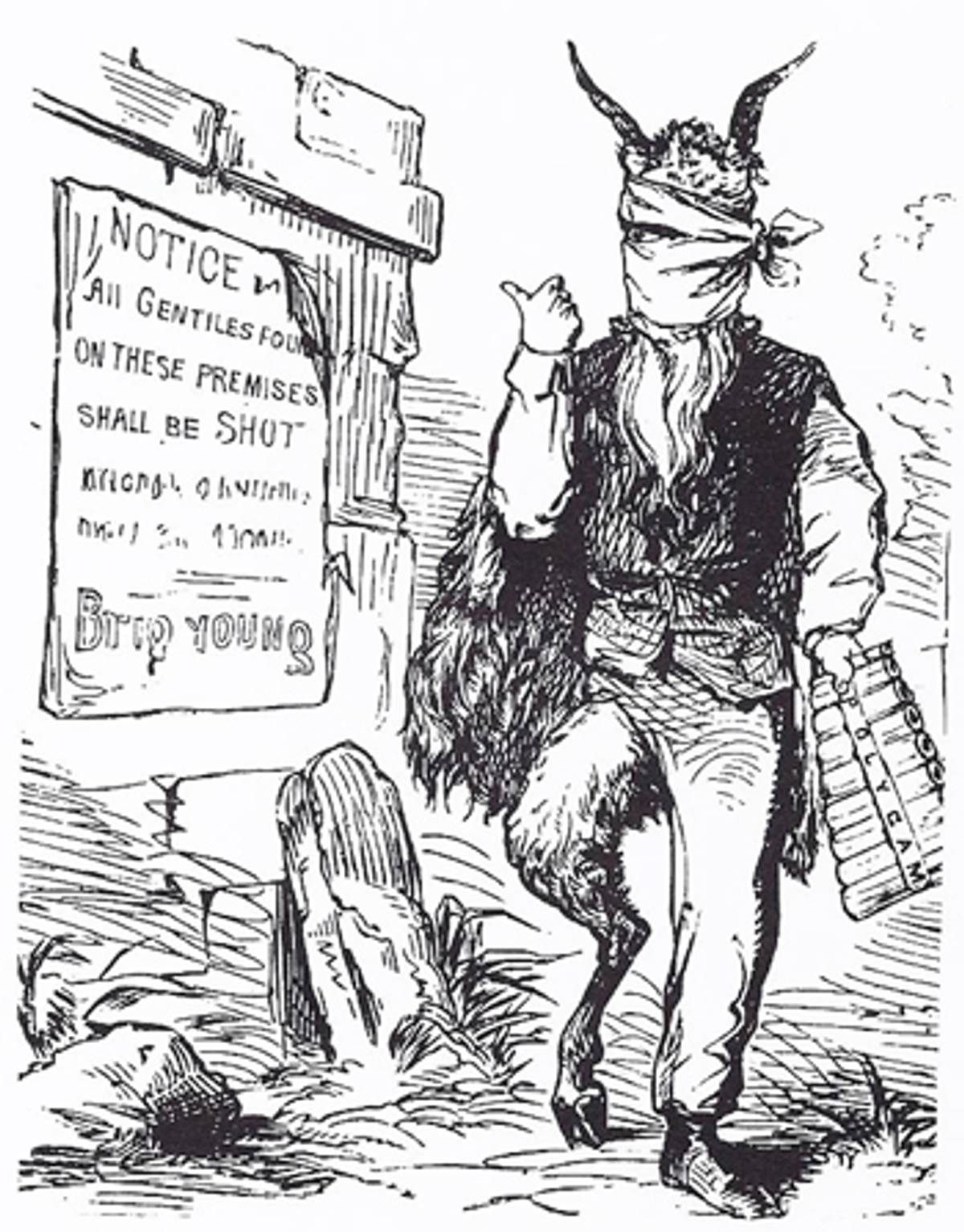

For Jews, the structure and form of these and other anti-Mormon broadsides are—or ought to be—all too familiar. Claims that a covert cabal of powerful Jewish interests seeks to suborn others to their sinister agenda have been commonplace for centuries, with today’s insinuations about the Israel Lobby being only the most recent manifestation. Like such conspiracy theories about Jews, allegations that Mormons have insidious designs on the American government are intended to discredit and demonize their targets in order to exclude them from political life. Having long been attacked by opportunistic demagogues, as well as had our loyalties questioned, we Jews know just how painful such slanders are—and what can happen if they go unchallenged.

***

Scores of Mormons have served faithfully in the United States Congress and other top governmental positions; currently, six senators and nine members of the House are Mormon. Mormons have also occupied numerous ambassadorships and Cabinet positions, from solicitor general to secretary of education. Under President Eisenhower, Ezra Taft Benson served as secretary of agriculture and as one of the 12 apostles of the LDS Church. (Afterward, he became the church’s 13th president and prophet.) And although few Americans are aware of it, the highest ranking and most influential Mormon in American politics today is not Mitt Romney—it’s Democratic Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid.

Given the preponderance of prominent Mormon politicians, it’s hard to escape the conclusion that if there really is a clandestine Mormon blueprint for U.S. domination, Latter-day Saint lawmakers have done a remarkably poor job of executing it. Those pundits fretting about the advent of Mormon theocracy never get around to explaining why all of these officials have always seemed much more interested in advancing the interests of party and country rather than imposing church doctrine on the unsuspecting American masses. (I, for one, would love to hear how LDS Sen. Orrin Hatch’s penchant for composing Hanukkah songs fits into this nefarious scheme.)

“In many hundreds of hours of political discussion in my family, nobody has thought that we had a duty as Mormons beyond our civic duty to step up and try to make our country a better place,” Joseph Cannon, former chairman of Utah’s Republican party, told me in an interview. As a fifth-generation member of one of the most powerful Mormon political families, he would know. (Cannon ran for Senate in 1992, his brother is former Congressman Chris Cannon, and his great-grandfather, George Q. Cannon, served as Utah’s pre-state territorial delegate to Congress and was famously expelled from the body in 1882 when Utah refused to give up polygamy.) “I can say that the root of my own family’s interest, and I think that this is reflective of the church, is that we have a duty to help make things better wherever we are,” Cannon explained. “There are Mormons in Parliament in England, one Liberal and one Tory, and I’m guessing their motivation, like ours, is just public service and duty.”

So, what about those church prophecies that supposedly call for Mormons to take control of the U.S. government? Salon’s Sally Denton makes much of the so-called “White Horse Prophecy.” Allegedly uttered by Joseph Smith, the founder of the church and its first prophet, the prophecy predicts that at some moment of future national crisis, the Constitution will “hang by a thread” and a group of Mormons known collectively as “the White Horse” will save it and, possibly, run the government. As the 1902 diary entry of a practicing Mormon who recorded the prophecy states, “Power will be given to the White Horse to rebuke the nations afar off, and you obey it, for the laws go forth from Zion.” Present-day critics draw a straight line from Smith to an inevitable Mormon theocracy.

There’s only one problem with this theory: The White Horse prophecy is not accepted by the LDS Church, and most Mormons have never even heard of it. Joseph F. Smith, the sixth president of the church, called it “ridiculous” and “simply false.” A century later, the church has not changed its stance, releasing an official statement in January 2010 that “the so-called ‘White Horse Prophecy’ is based on accounts that have not been substantiated by historical research and is not embraced as Church doctrine.” Cannon, for his part, can’t remember even hearing the words “white horse prophecy” since he was a teenager.

Casting the prophecy as a cornerstone of Mormon identity or Romney’s worldview, then, is akin to the age-old anti-Semitic practice of lifting decontextualized statements about gentiles from the Talmud, framing them in the worst possible light, and then claiming that such sentiments represent what all modern Jews think, when the reality is that most are completely ignorant of the text at hand or lend it no credence. As Cannon put it, when outsiders criticize modern Mormons, they “tend to seize upon things that just don’t have a lot of resonance with current-day Latter-day Saints.”

Indeed, contemporary Mormons echo their leadership’s dismissal. “The White Horse prophecy is pretty much bogus,” Orson Scott Card told me. While best-known for his novel Ender’s Game, Card is also a lifelong Latter-day Saint. He authors a regular column on faith for the church-owned Deseret News and is a great-great-grandson of Brigham Young. (He served his LDS mission in Brazil, where he picked up the Portuguese language and Catholic culture that feature in the Ender’s Game sequel, Speaker for the Dead.) On the White Horse prophecy, Card is unequivocal. “It’s not regarded as doctrinal by the church, it’s not treated as Scripture, it’s not regarded as an authentic statement of Joseph Smith, and church policy is not guided by it in any way, shape, or form. Most Mormons are unaware of its existence.”

To test this proposition, I spoke to Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, professor of early American history at Harvard and a Pulitzer Prize winner. A committed Mormon, she serves as the faculty adviser to the Latter-day Saint Student Association on campus. She’s also edited a collection of essays about the lives of Mormon women and is currently writing a book on 19th-century Mormon diaries. “Every society has these little urban legends,” she said of the White Horse prophecy. “There may be people who take it seriously. I don’t know any.”

As a Massachusetts resident and a Mormon, Ulrich often gets questions from reporters about her impression of Romney, specifically how his faith and politics relate. She doesn’t offer citations from LDS scripture. “I point out that you’ve got to evaluate this person in terms of his own positions—and there’s a wide range of positions among Latter-day Saints,” she said. “He’s somewhat to the right of the mainstream church position on some issues and maybe not on others. So, you really have to look at what he says.”

Both Card and Ulrich find the charge of theocracy laughable. “The general stance of the church, and this would of course go way back into the 19th century, is ‘please leave us alone, protect our rights to practice our religion,’ ” Ulrich explained. “Yes, there was a unity of church and state for a time with Brigham Young as governor and head of the church. But they also helped fund the establishment of a Jewish synagogue in Salt Lake and welcomed Jews,” she added. She points to the LDS Articles of Faith—which originated with Joseph Smith in the 1840s—where Article 11 avers, “We claim the privilege of worshiping Almighty God according to the dictates of our own conscience, and allow all men the same privilege, let them worship how, where, or what they may.” As members of a long-persecuted minority religion, said Ulrich, “Mormons—of all people—are pretty protective of religious liberty.”

Card added that Mormonism, as an international missionary religion, would rather not be equated with the United States. “Can you imagine what the effect would be in Mexico, in Nicaragua, in Honduras, in China, if the Mormon Church was viewed as an instrument of the American government? It would be difficult for us to get our missionaries into countries that now accept them. This is actually quite perilous. Our primary mission as a church is to spread the gospel of Jesus Christ,” not to elect an American president. “So, those that think that Mormons are all universally united behind the idea of a Mitt Romney candidacy and that we’re just chomping at the bit to get control of the government of the United States—that’s the opposite of the truth. The truth is, Mitt Romney’s candidacy, leading to his election as president, would be perilous to the Mormon Church and would make our work worldwide more difficult.”

***

So, if the LDS Church and its adherents have no interest in taking over the American government and imposing their beliefs on others, why are an increasing number of commentators claiming that they do? Underlying these attacks on the loyalties and religious beliefs of American Mormons is not so much an attitude of prejudice as one of partisanship. After all, no prominent columnist imputed theocratic motives to Harry Reid when he ascended to the post of Democratic Majority Leader. And no one dared to mock the “magic underwear” of Orthodox Jews—tzitzit—when Joe Lieberman ran for vice president on the Democratic ticket, as pundits like Bill Maher and Maureen Dowd have done when it comes to Romney’s Mormon undergarments. (And if one doubts that tzitzit can be just as disconcerting to the uninitiated, go read Philip Roth.) It is only when a conservative Republican Mormon emerged as a presidential frontrunner that these issues suddenly became pressing matters of national concern. The very real and unprecedented possibility of a Mormon presidency opened the door to very real and unprecedented political rancor.

Tellingly, the sort of specious argument that Salon’s Denton makes about the perils of Mormon theocracy is exactly the sort of conspiracy theory that the same publication rightly denounces when it comes from Robert Spencer about Muslims and the threat of creeping Sharia. The latter narrative is clearly seen as false, but the equally problematic nature of the anti-Mormon argument is obscured by partisan blinders.

But one need not agree with Romney’s policies to recognize that it is wrong to play Da Vinci Code with his faith’s traditions, picking and choosing questionable texts from LDS history and using them to demonize an entire diverse religious community. One need not agree with those policies to understand that Romney’s positions are his own, and not dictated secretly by his church, which sometimes openly advocates for diametrically opposed policies.

Ultimately, there’s only one way to understand Mormons. “Meet a Mormon. Talk to a Mormon. Not about the church—just find out who we are,” said Card. “You’ll find out we’re perfectly normal. We have the normal percentage of wackos, like any other group—you can find wacko Baptists, wacko agnostics, and wacko college professors—but most of us are ordinary people. We keep up our yard, we pay our bills, we buy our houses, pay our mortgage, do our job, work hard.

“We have no more ambition to rule the United States than any other religious group. Nobody’s trying to create a Baptist president, nobody’s trying to create an atheist president,” he said. “If we have a Mormon as president, that doesn’t mean it’s going to be a Mormon presidency—it’s going to be an American presidency. Just like all the others.”

Yair Rosenberg is a senior writer at Tablet. Subscribe to his newsletter, and follow him on Twitter and Facebook.

Yair Rosenberg is a senior writer at Tablet. Subscribe to his newsletter, listen to his music, and follow him on Twitter and Facebook.