Reflections on Herman Wouk

The first novel I ever read was by Herman Wouk. Now, 60 years later, he’s publishing yet another one.

When I became a senior citizen a few years ago, someone asked what public personalities had spanned my entire life. After giving it some thought, the only two names I could come up with were Queen Elizabeth and Yankee announcer Bob Sheppard (who has since gone to that great broadcasting booth in the sky).

I had forgotten the third: Herman Wouk.

What brought this anecdote to mind was the arrival of a new Wouk book, Sailor and Fiddler: Reflections of a 100-Year-Old Author, being published this month by Simon and Schuster. Wouk’s City Boy was the first novel I ever read, and here he is still turning out books almost 60 years later.

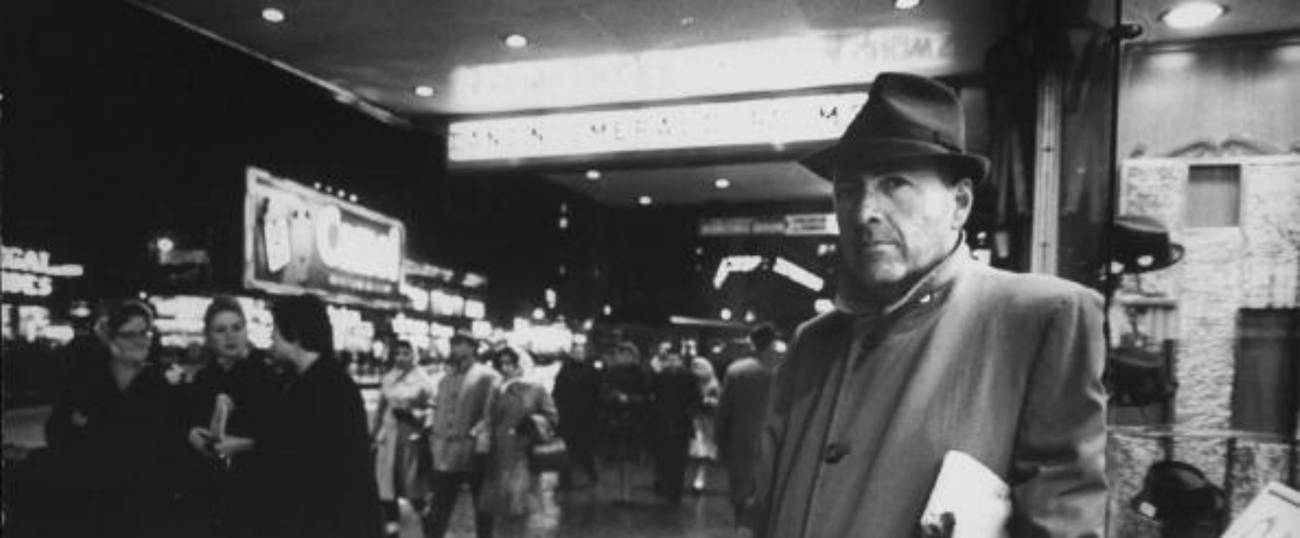

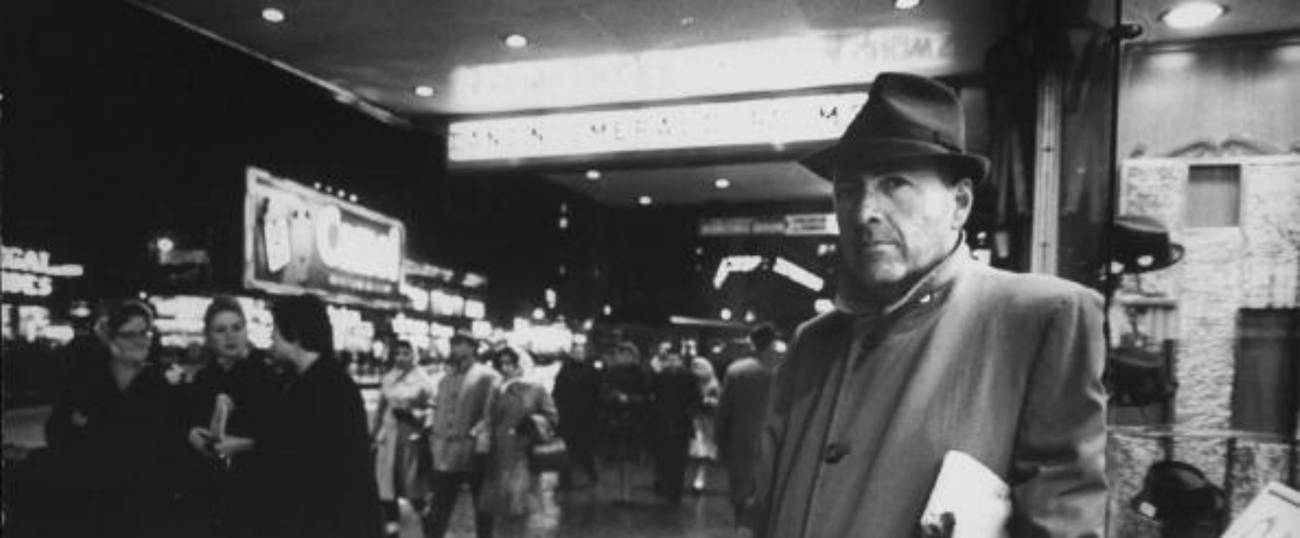

Three years ago I offered some reflections on Wouk’s newly published novel, The Lawgiver, which, despite its often-archaic language and usage, contained sweet surprises. Sailor and Fiddler has similar pleasures. In its modest 135 pages, Wouk, who turned 100 last May, reflects upon his over 80 years in the public eye, and chronicles the twists and turns that took him from writing gags for a virtually forgotten radio celebrity in 1937, to becoming one of 20th Century America’s most successful and celebrated (if not by critics) authors. (Wouk may be the last remaining celebrity for whom having appeared on the cover of Time magazine remains meaningful). Fans of Wouk’s prose will appreciate both the thought process that went into building the structure of his novels, especially the World War II epics The Winds of War and War and Remembrance, as well as the depiction of the arduous work he undertook to fulfill his desire to “bring the tragedy of the Holocaust to life” at a time when it was at the margins of the world’s consciousness.

As he put it: “…Here was the Task itself. The Russians had borne the brunt of Hitler’s assault on civilization. Research could do only so much; extensive travel had to be part of the job starting with the Soviet Union…I traveled in that bleak miserable dictatorship for two months: no fun at all, but fully as compulsory as going to Germany had been [for the Winds of War]. We went twice to Auschwitz. We visited Terezin (Theresienstadt), the Czech locale of the “Paradise Ghetto.” In Iran we managed to go to Tehran, where Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill met and forged the grand alliance that won the war…We traveled the track of Natalie Jastrow, fleeing a German SS pursuer with her baby and her uncle down from Siena to the ferry to Corsica, and from there by ship to Marseilles; all this while I wrote a novel more than a thousand pages long.”

In 1971, not long after I received my two-volume set of the Winds of War from the Literary Guild (remember mail order “book clubs?”), I traveled to Israel on vacation. Since each volume ran to almost 500 pages, I decided to pack only the first one for my short trip, which I consumed within days of my arrival, only to spend the next week haunting every bookstore I passed, seeking, in vain, to obtain another copy and learn more about the fate of the “Pug” Henry clan.

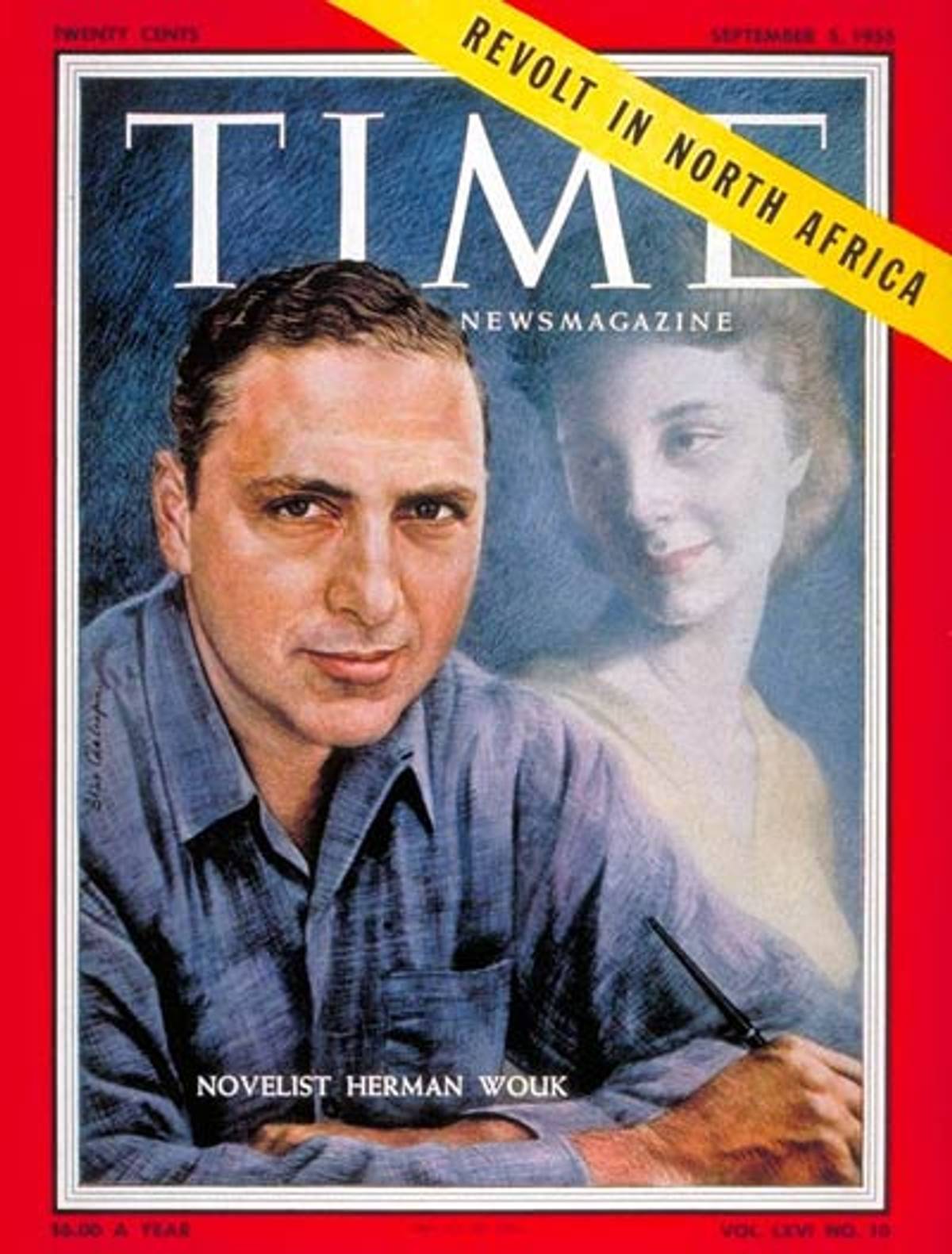

The Fiddler aspect of the title of Wouk’s new book refers to what the author calls the “spiritual journey” that has coexisted with his literary side: the Orthodox Jewish and ardent Zionist perspective that infused every aspect of his life. At one point he describes seeing photographs of Israeli fighter jets, landing and taking off, on the U.S. nuclear aircraft carrier Theodore Roosevelt and notes: “…I was struck, all of a heap, by the amazing changes in the fortunes of my Jewish people during the hundred years of my life.” Sailor and Fiddler is dedicated to both Colonel Mickey Marcus, the American who David Ben Gurion dubbed “the first Jewish general in two thousand years,” whose accidental death in Israel’s War of Independence was recounted in the film Cast A Giant Shadow, and Colonel Ilan Ramon, the Israeli astronaut who was killed in the crash of the space shuttle Columbia.

Wouk concludes the memoir by stating that “The view from 100 is…illuminating and surprising. With this book I am free: from contracts, from long-deferred to-do books, in short, from producing any more words. I have said my say, done my work.” How many of us can, in all honesty, claim that?

Morton Landowne is the executive director of Nextbook Inc.