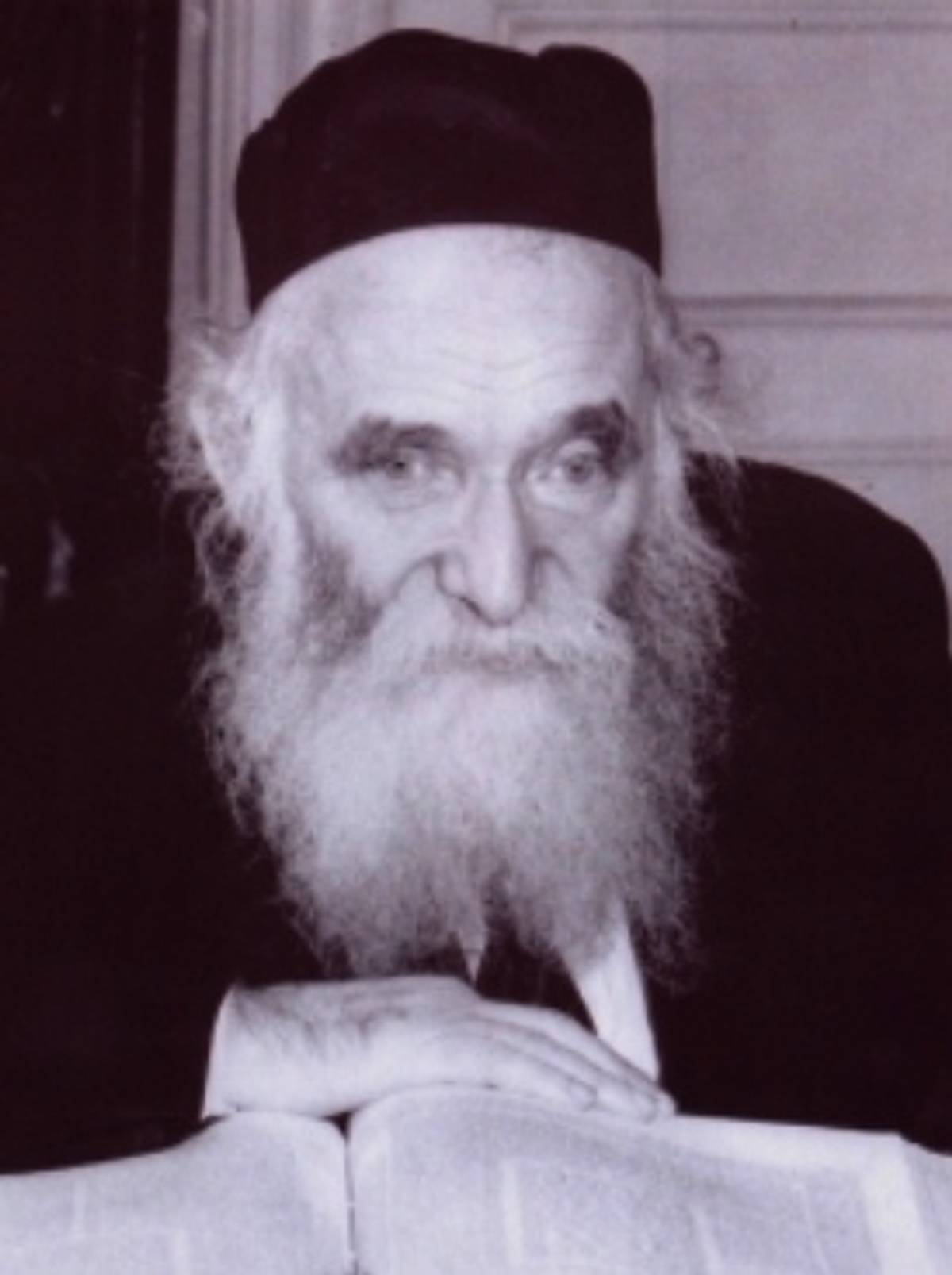

Remembering Rabbi Aaron Kotler and the Yeshiva of Kletzk

Kotler, who established an important yeshiva in Lakewood, New Jersey in 1943, strived to educate and look after students. ‘Let Torah flourish in America, he challenged.’

Last Friday marked the 54th yahrzeit of Rabbi Aaron Kotler, a leading Rosh Yeshiva in pre-WWII Europe who formed Lakewood’s Beth Medrash Govoha in 1943. At his passing in 1962, he was the recognized leading authority in the Yeshiva world, with his influence impacting the Jewish scene both in the United States and in Israel. He was a visionary, one of the key figures who led the renaissance of Torah Jewry during the post-War era. A prodigious Talmudic scholar who used every spare moment he had for Torah study, he recognized his unique talents and place in history to help build Jewry anew.

No matter was too large or too small for Rabbi Kotler. He worked in Va’ad Ha-Hatzolah offices urging rescue efforts, and marshaled U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau’s support for assistance in sending refugees money. His West Side apartment in New York City became the address for individual letters all corners of the globe with individual requests. The letters reflected their belief in his concern for them, and his ability to tend to their plight. He corresponded with his students trapped in Samarkand after being shipped to Siberia by the Soviets in 1941, sending them care packages, with letters signed, “Your friend who will not forget you.”

The pocket pads that he carried with him to Israel whenever he traveled there in the 1950s and early ’60s contained pages of handwritten notes of personal regards from people in America to send to relatives living there, and a few dollars to deliver to them. He had more weighty issues on his mind, too, such as conferring with other Torah leaders, and mapping out the future of Chinuch Atzmai, the independent Torah education system that he helped organize, and tending to his duties as Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshiva Etz Chaim.

But the individual was paramount in Rabbi Kotler’s mind.

Rabbi Kotler looked forward optimistically at what could be built, and directed his energies accordingly. A physically short man with an inherent shy personality and a rapid staccato delivery does not necessarily make for a world renowned leader, but his charisma moved masses. His inborn drive for building and growth galvanized him and inspired those who came into his orbit.

As Rabbi Kotler arrived in San Francisco on Passover Eve in 1941, after escaping both the German and Soviet regimes, he made his way by train to the East Coast. A delegation of rabbis, students, lay rescue leaders, and journalists greeted him at the Pennsylvania Station platform, welcoming him to safety on these shores. If they figured that Rabbi Kotler would appreciate resting for a few days after traveling across three quarters of the way across the world to reach that platform, they were in for a surprise. At a welcoming reception held that day in his honor, he exhorted the attendees to save the Jews trapped in Europe, including his own students and, looking ahead, he declared that the we could rebuild on these shores what Hitler was destroying in Europe. Let Torah flourish in America, he challenged.

“If one had to date the beginning of the current struggle over Jewish identity,” notes Samuel G. Freedman, author of Jew vs. Jew, “then it might well be Passover eve in 1941. On that day, an Orthodox rabbi named Aaron Kotler reached New York as a refugee from the cataclysms in Europe.”

Rabbi Kotler galvanized the Va’ad Hatzolah members with new ideas and rescue plans, including drafting the resolutions for the Rabbis March on Washington in 1943. Though he initially occupied himself completely with relief efforts, he opened a yeshiva in Lakewood two years later after arriving stateside. Thirteen students, some of whom were married, was a far cry from the over 300 he had just a few years earlier in Kletzk. But, nonetheless, a beginning.

The yeshiva purchased a hotel on 6th Street which was suitable for all its needs, but Rabbi Kotler, ever the visionary, was thinking long-term. In 1947, an architect rendered plans for a yeshiva study hall to house 250 students. The yeshiva only had 50 students at the time, and would only reach that number 15 years later, when Rabbi Kotler passed away.

But the yeshiva wasn’t his first priority. He viewed children’s education at the key for Jewish continuity. Through Torah Umesorah in the United States, and Chinuch Atzmai in Israel, he poured his efforts into creating a network and support system for schools to provide traditional Torah education for children.

When members of the yeshiva’s administration lamented that his fund-raising efforts for Chinuch Atzmai adversely affected the yeshiva’s precarious financial plight—they were five months behind—Rabbi Kotler replied, “What should I do, but the education of 40,000 children in Eretz Yisroel is more important than my own yeshiva,” he said regarding Torah Umesorah. “Let the yeshiva suffer. “So long as thereby Jewish children will at least know the aleph bais.”

Rabbi Kotler fully understood the enormity of the Holocaust on a personal level. He lost family members. His son, recently engaged, had to escape to Israel, while his fiancé escaped to Shanghai, only married nine years later. Most of his 300 students trapped behind in Europe perished in the Holocaust, despite his best efforts to save them.

Yet he understood that the main focus now was to channel his feelings to rebuild, and move onward, as perhaps aptly described in his own words. A student of Kletzk yeshiva that survived the war, Rabbi Eliyahu Moshe Bloch authored “Ruach Eliyahu,” a collation of insights by Rabbi Eliyahu of Vilna, best known as the “Vilna Gaon.” Rabbi Bloch appended the volume with a list of 220 names of his fellow Kletzk students who were tragically murdered during World War II, memorializing their names for future generations. In Rabbi Kotler’s moving six-page approbation, written in a beautifully flowing rabbinic Hebrew, he expresses his feelings about his students who perished:

I sincerely believe it my obligation to write something in the pure memory of the exceptional Torah students who excelled in Torah, fear of heaven, and good character, who could count in their number numerous Torah giants, astute experts of incredible talent who were significant innovators. They even merited sanctifying God’s name by literally giving their lives to Torah study and observance under conditions that could make their life forfeit at any time, as rabbis who witnessed them have related.

One should also mention the pious rabbi and ga’on, our teacher and master Rabbi Yosef Aryeh Nandik of blessed memory (may God avenge his blood), mashgiach of our yeshiva and one of the greatest ethicists of his generation.

On account of my many burdens, the heavy yoke placed upon me in teaching Torah to the public, and the other countless responsibilities relating to Torah, I have not had enough time – by any measure – to give matters their due weight. Since one may not abridge when expansion is called for, I am forced to leave it for another time (if God wills it) and am sorry that I cannot do so now. I hope that the holy Torah scholars who are beloved to me in life (may we all live long) will forgive me this in the world of truth.

With these paragraphs, Rabbi Kotler expresses his deep feelings of kinship to his students, understanding the enormity of the tragedy, while simultaneously asking forgiveness for not doing for their memory, due to his many responsibilities.

His passing on Thursday morning, November 29, 1962, seemed to be a watershed moment for the communities that consulted him for guidance. His fellow rabbis, roshei yeshiva and the lay leaders were inconsolable. The outpouring of grief, as evidenced by the 25,000 people who gathered in Manhattan’s Lower East Side for the funeral the following Sunday, and another 50,000 in Israel on Tuesday, where he was laid to rest, reflected the sense reverence and esteemed respect in which he was held. They felt bereft of the leader who willed himself to build and take charge. Now what, they asked?

Looking back, though, Rabbi Kotler planted the seed for the flourishing Torah community in the U.S.. His students opened schools, yeshivas, and kollels across the globe, and became active in their respective communities: 14,000 alumni of Beth Medrash Govoha have established 1050 institutions across the globe, educating the future generations from learning aleph-bais to expounding on Rabbi Kotler’s deep Torah novella on intricate Talmudic concepts.

His yeshiva in Lakewood, first led by his son and now his grandchildren, has expanded to include over 7,000 students with three campuses around Lakewood. The former resort hotel town has become a sprawling metropolis and a center for Jewish life.

When we pause to remember a Torah leader as Rabbi Aaron Kotler, we reflect how each generation can meets its unique opportunities and challenges, with forward-thinking strategies based upon past and eternal traditions. With the advantage of time, one better appreciates the determination and perseverance that “the Greatest Generation” overcame to build the communities and culture we often take for granted today. The members of that generation lived through multiple wars, severe financial depressions, and took the initiatives to create infrastructure, tools, and technologies to make the world a better place for them and their children.

An alumnus of Beth Medrash Govoha, Rabbi Moshe Rockove is presently an archivist at the yeshiva. He resides with his family in Lakewood, New Jersey.