The Obscenity of Blaming Zionism for the Holocaust: A Response

Wolfgang G. Schwanitz answers Tablet’s review of his and Barry Rubin’s book

In his Feb. 3 review in Tablet, David Mikics misrepresents our book Nazis, Islamists, and the Making of the Modern Middle East. It is not a biography of the grand mufti of Jerusalem Amin al-Husaini, though one is in the making, and Mikics fails to show how it compares to related works. He bit off more than he can chew. Thus, he exaggerates: the book, he alleges, purports to demonstrate that “Zionism caused the Holocaust.” He then calls this invention “their logic, a “flawed conclusion,” as if he were refuting what he has in fact attributed to us. In the light of Barry Rubin’s passing—see the obituary by Lee Smith in Tablet—I will answer here.

Zionists rescued Jews on many occasions: in the attempted genocide in Palestine 1915 to 1917, in the Holocaust of World War II, and thereafter in global pogroms and Middle Eastern conflicts. As we have shown, the seeds of the State of Israel stem from the advent of Zionism and the League of Nations. At its 1922 San Remo conference this world body assigned the mandate of Palestine to Great Britain as 52 states recognized historical ties of the Jewish people with Palestine and favored the “reconstituting of their home” there.

As we reveal, the Kaiser brought pressure on his allies, the Young Turks, to issue an “Ottoman Balfour Declaration.” After half a year of talks with Jews, interior minister Talaat Pasha delivered it on August 12, 1918: Istanbul’s council of ministers welcomes a Jewish home in Palestine by immigration and colonization. Thus London in 1917, Berlin in 1918 and the U.S. Congress in 1922 all recognized a Jewish home between the Mediterranean and the Jordan. Ideally, Israel was conceived after Russian pogroms of 1881, the birth of Zionism in 1897, and a U.S. statement to the Christian world (and the Ottoman sultan-caliph) on Zionism in 1907. Mikics’s question, “Did Zionism cause the Holocaust?” leads to ahistorical notions that end in “Jews and Zionists brought genocide upon themselves.” This expressed Amin al-Husaini, and one of his successors, Mahmoud Abbas in his 1982 Muscovite Ph.D. on some secret ties between the Nazis and Zionists.

Mikics toys with a Great Man Theory of History. But mass murderers, such as Mao, Lenin, or Hitler were no great men. The reviewer contradicts himself by insisting that those tyrants “really changed the world.” Well, so did al-Husaini’s Islamists. But not as Mikics, oblivious of the regional history, claims: “So, without the grand mufti, no Israel.”

Has the reviewer an ideological agenda? He rejects new facts and evidence or stuffs them into dusty approaches. Since Mikics did not introduce the reader into the larger argument we made, I shall do this briefly. He claims the German ties to Islamist movements of the Middle East do not explain Islamic radicalism; it can be seen only part of the background. From which Turkish files, Iranian records or Arabic memoirs he comes to this? We have unearthed a most chilling German mosaic in Middle Eastern history that was long French and British dominated. At the same time, however, I take care to warn against Mikics’s oversimplification: it does not explain it all. Complex connections can only be traced by multidimensional and multi-archival approaches from all sides involved in the conflicts.

Look, for example, at the father of German jihad, Abu Jihad, Max von Oppenheim, the subject of a brilliant book by Lionel Gossman that was reviewed by Walter Laqueur in Tablet last year. Gossman’s book is based on broad research in American, European and Mideastern papers. Laqueur writes that if von Oppenheim is recalled, it is as an unlikely and unsuccessful proponent of jihad. The grandson of the founder of a German Jewish bank was fascinated by the Middle East. As the Kaiser’s man, he settled in Cairo in 1896.

In October of 1914, after the war’s outbreak, von Oppenheim submitted his master jihad plan. He argued for enlisting pan-Islamism in the fight against Britain, France and Russia. Islamism had been preached for decades before the Great War. In 1940, von Oppenheim offered his “Union-Jack-plan” to Berlin, again suggesting the use of Islamist revolts as a weapon against Britain’s crucial oil interests in the Middle East and lifeline to India. He focused also on Palestine. This Abu Jihad suggested that Jews living there before 1914 should be permitted to stay. All others, however, should be removed—a proposition taken over by Yasir Arafat’s National Charta. Mikics does not know what to do with von Oppenheim in the Laquer/Gossman debate. This German was the incarnation of Berlin’s policy to mobilize Islamists and Islamism in its foe’s colonial back twice, 1914 and 1940.

The reviewer sometimes contradicts himself: “Despite the overblown claims for the mufti’s central role, Rubin and Schwanitz do an illuminating job showing the extent of the partnership between Germans and Islamists; this is by far the best part of their book. Germany had a long history of encouraging Jihadism even before Hitler’s rise to power. But Max von Oppenheim is not any more responsible for 21st-century suicide bombers than the mufti or Hitler is.” No power of ideas in the Middle East, nobody responsible?

As an expert of English literature, the reviewer pays no attention to our following of the eight Muslim brotherhoods in von Oppenheim’s 1914 jihad plan like the al-Mahdiyya in Sudan, the as-Sanusiyya in North Africa, the al-Ikhwaniyya in Saudi Arabia or the al-Qadiriyya in Iraq as platforms in the German-Ottoman jihadization of Islam in World War I. Most are still active. Does this explain nothing or “just in the background?” In 1928 child number nine, Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood, was added, for the axis between Germans and Islamists went on after the war also. There was no stop just for a lost war. This Brotherhood followed suit with rising Nazism. It served as a blueprint for al-Qaida.

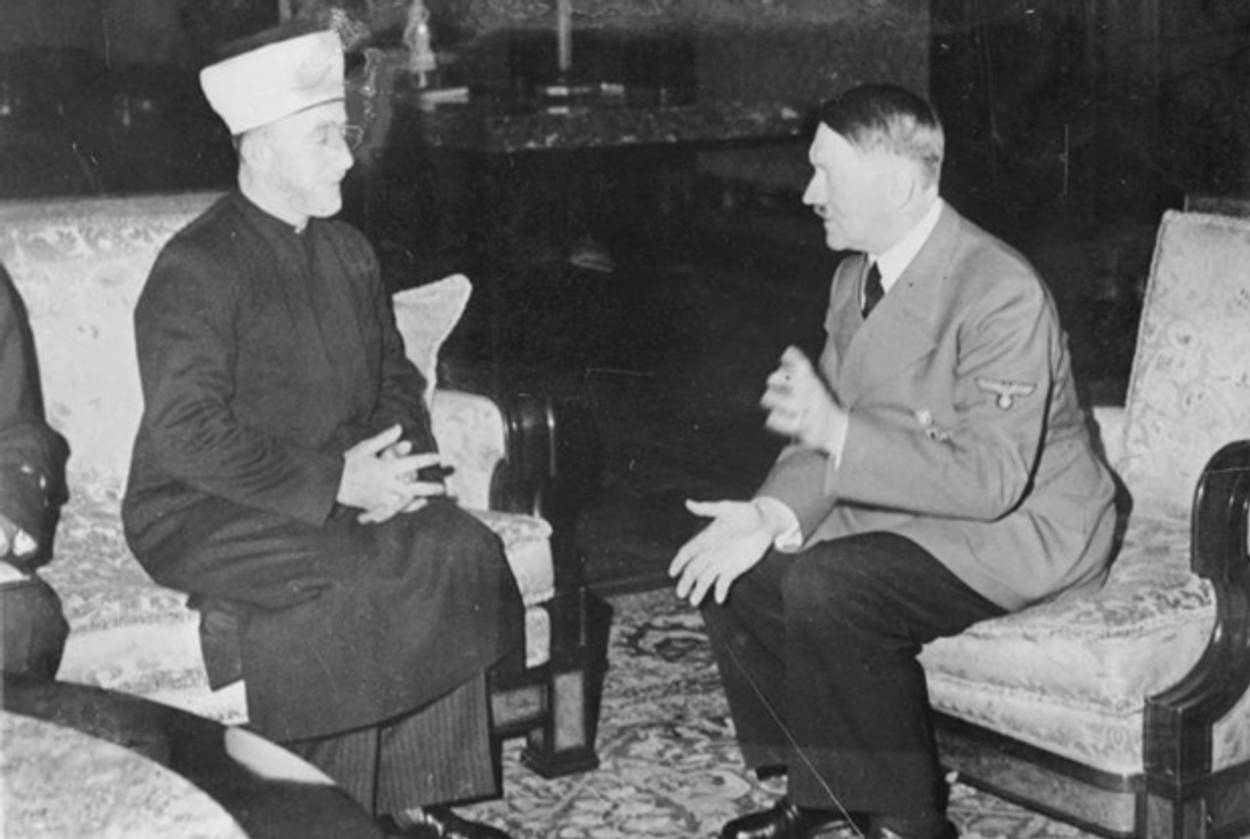

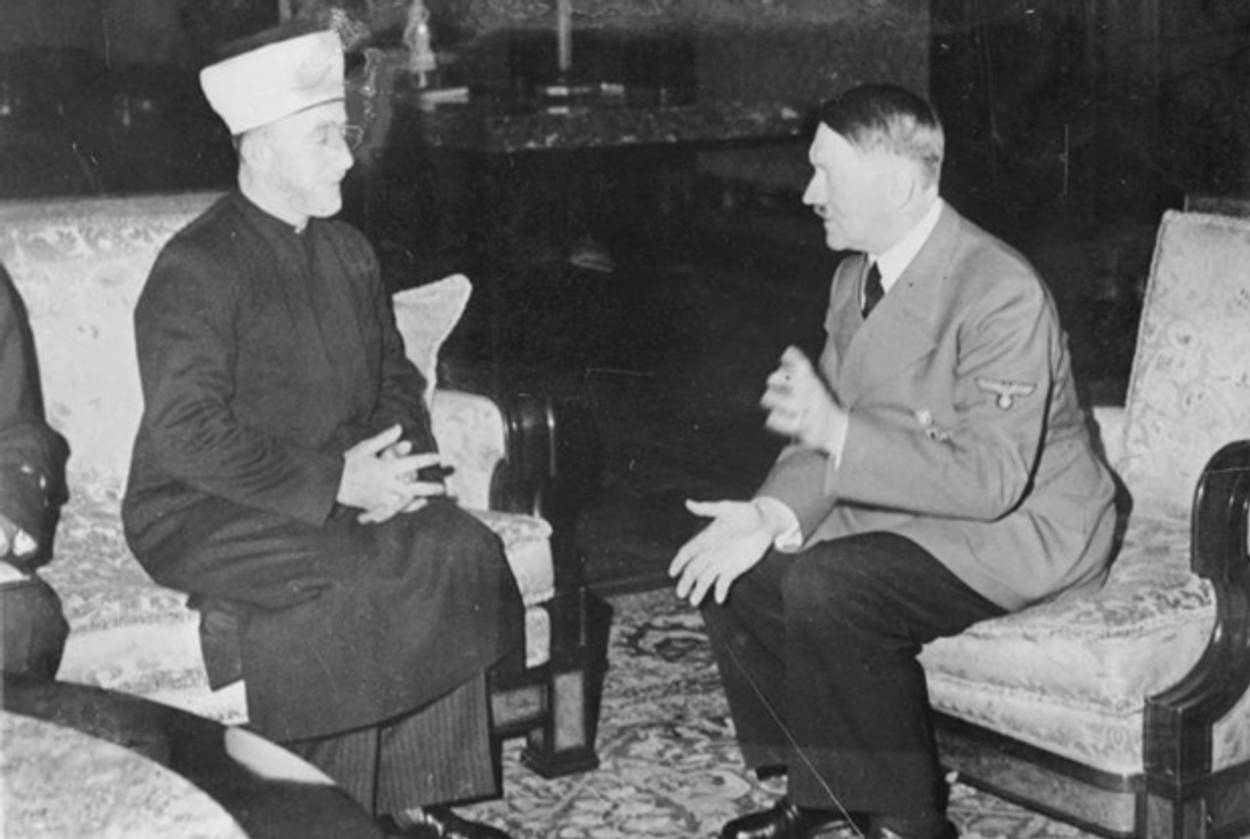

Nor did the reviewer carefully weigh our points about November 28, 1941. On that dark afternoon, Hitler received al-Husaini: “the principal actor” in the region, “a realist, rather than a dreamer.” In 95 minutes, Hitler told him of his plan: to kill the Jews of Europe, the Middle East, and globally. On that day, the “fuehrer” believed he had defeated Moscow.

Therefore, he ordered the Middle East as the next battle ground. The Nazi told the Islamist that as soon as Axis troops reach the region in a pincer grip via the Suez Canal to Palestine and via the Caucasus to Iraq, Iran and India, al-Husaini will be the man to build a Jew-free Greater Arab Empire. That night, Hitler made five points. Four were given in writing. But his Fifth Decision was presented only orally: on the state secretary level, to meet within the next ten days for “managing” the Final Solution, at first within Europe.

Hitler got advanced news of a Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. So he chose the date two days after this expected raid, December 9, when all would be distracted, to get secrecy for the conference that organized the Holocaust. The day after his talk to al-Husaini, thirteen Nazis were invited for that “meeting of death” at Berlin’s Lake Wannsee. But a Soviet offensive obliged Hitler to postpone the Wannsee Conference to January 20. The next day, his key diplomat Fritz Grobba confided to al-Husaini the results of that conference.

The change of date and Hitler’s dragging out news on his meeting with the grand mufti for ten days has obscured the Nazi-Islamist genocidal pact. Hitler relied on accomplices. Al-Husaini was his most radical non-state non-European collaborator. After his Farhud pogrom in Iraq, he asked Hitler, on June 2, 1941, to visit him. A clock was ticking. He insisted to stop all legal Jewish emigration. Hitler made all genocidal decisions from June to December 1941, including blocking legal Jewish travel shortly before he received him. The cleric solved two problems: no Jewish influx and a Nazi option for the Middle East.

We do not say, as the reviewer claims, that Amin al-Husaini “is nothing less than the architect of the Final Solution.” But he pushed the Nazis ahead. Hitler had published his goal in his book of 1925: gassing Jews, destroying the “Judeo-Communist Empire.” The chief Nazis—Adolf Hitler, Heinrich Himmler, and Adolf Eichmann—remain the key perpetrators. Hitler is most responsible for the Holocaust, though al-Husaini swayed him along the way and made no secret of his four years of interventions with the Nazi leaders as soon as exchange projects of Jews for German civilians or prisoners of war came up. He boasted in his 1999 Damascus memoirs that he was successful: Himmler promised him to not let Jews go to the Middle East. Mikics missed this. Al-Husaini slammed shut the last exit doors of a burning house to keep the Jews inside.

In addition, the grand mufti got them killed by his Muslim SS troops in the Balkans and in Soviet Asia. He trained imams and mullahs for Nazi troops, spied for them, sent terror units to Palestine, and incited hatred against North African Jews and resistance against the Allies, especially America. In late 1941, he put America also on his target list. Only five decades later Osama bin Laden did the same. We have shown how their ideology of Islamism remained alive throughout those decades and served in today’s trouble as well.

In his memoirs, al-Husaini admitted that Himmler told him of having killed three million Jews by mid-1943. Yearly, he met with SS mass murderers and visited death camps. As a revered leader, he aroused many Islamists through broadcasts, prepared for and started the Middle Eastern genocide. At the same time, he blocked all British proposals for liberal compromises. As historians, we showed the missed opportunities and alternatives. This does not mean at all that “Rubin and Schwanitz make the astonishing claim that al-Husaini is nothing less than the architect of the Final Solution.” This would be wrong.

Still, al-Husaini’s regional and global Islamism guided his heir Yasir Arafat, anointed by him in late 1968. He became rejectionist as well. Mikics is right on this score: the sympathy with Nazis runs deep in the Middle East. But why? In addition to an old tribal anti-Jewish tradition, this region became the only major part of the world that hired many thousands of escaped Nazis to continue Jew-hatred, anti-liberal agitation, while avoiding any critical inquiry into this recent past, into the German-Ottoman jihadization of Islam, into the Nazi-Islamist genocidal axis and after 1945 into the West European hideouts of Muslim Brothers and other Islamists. In fact, Europe and the Middle East had exchanged their radicals: Nazis versus Islamists. Add to this the use of yet another totalitarian strain, from the Soviets. Whether the 2011 Mideastern revolts will start to remove those strains and lead to a new historical self-awareness by liberal Muslims and to fewer Islamists champions of jihad and sharia beyond the old ideology, as we have traced it in our book, indeed, only time will tell.

Wolfgang G. Schwanitz is a Middle East historian living in the United States. He authored 10 books and edited 10 books, among them Germany and the Middle East 1871-1945; Islam in Europe, Revolts in the Middle East; Nazis, Islamists, and the Making of the Modern Middle East (with Barry Rubin) and yearly The Middle East Mosaic 2015-2019. He is the Bernard Lewis fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute in Philadelphia.