The Rothschilds Return to New York

A review of Rothschild & Sons, an off-Broadway revision of Harnick, Bock and Yellen’s musical The Rothschilds

A musical—a period piece about a Jewish man and his relationship with his wife and five children as he struggles with anti-Semitism and changing times in Europe—is back in New York City. This story may sound familiar, of course, but it’s not the soon-to-open Broadway revival of Fiddler on the Roof. Rather, it’s the return of The Rothschilds, a musical you are less likely to have seen in your synagogue’s basement.

In addition to a common narrative, the two theater productions have another aspect in common: Their songwriting team, Sheldon Harnick and Jerry Bock, wrote The Rothschilds in 1970 while the original production of Fiddler was still on Broadway. The Rothschilds—a musical about the real-life Jewish banking family’s rise to prominence as they struggled with anti-Semitism in Europe from the 1770s through the 1810s—debuted in 1970. While not a smash hit like its sister show, The Rothschilds ran for a year and still managed to garner two Tony Awards (while receiving 7 additional nominations). It also had a revival off-Broadway 20 years later in 1990.

Composer Bock died in 2010. But lyricist Harnick and the show’s book writer, Sherman Yellen, decided to revisit the material over 40 years after its Broadway debut. They drastically rewrote the book, and also cut or changed many of the songs, even adding numbers that didn’t make the cut of the original run. This new version of The Rothschilds began performances on October 6 and runs through November 8 at the York Theatre off-Broadway. But it’s so different from the Broadway incarnation, it bears an altered name: Rothschild & Sons.

Rothschild & Sons focuses on the family patriarch, Mayer Rothschild, and his origins as an ambitious young merchant living in the 18th century Frankfurt ghetto. Anxious to make something of himself in a world that openly despises Jews, he marries, has five sons, and ultimately, by use of his quick wit and perseverance, transforms his family into an international banking empire—all while still looking for a way to tear down the ghetto walls.

This new production is surprisingly endearing, and, despite the longer title, is leaner in almost every way with a modest set, shrunken cast, and shortened running time. Most edits to the show are smart, which includes the cutting of some less memorable or important songs, such as the droning “Hymn: Give England Strength” (the fewer songs of gentiles singing about how exclusive and aristocratic they are, the better). Perhaps the only nod to extravagance in this trim production are the costumes (Carrie Robbins). The period clothing draws distinction between Jewish and gentile worlds and tracks the Rothschilds’ rise to the top. In one scene, the Rothschilds look more or less like they stepped out of Hasidic Borough Park, while Prince William of Hesse is so foppish he could have stepped out of a Monty Python routine.

The production saves most of its energy for the family itself. For example, Mama Rothschild, Gutele, played by Glory Crampton, has had a personality makeover, exhibiting as much chutzpah as her husband and sons. She even now, ultimately, takes an active role in making decisions for the family business, such as urging her sons to take the most daring risks of their lives. (Notably, making no appearance in any version of this musical are the Rothschild daughters, of whom in real life there were five.)

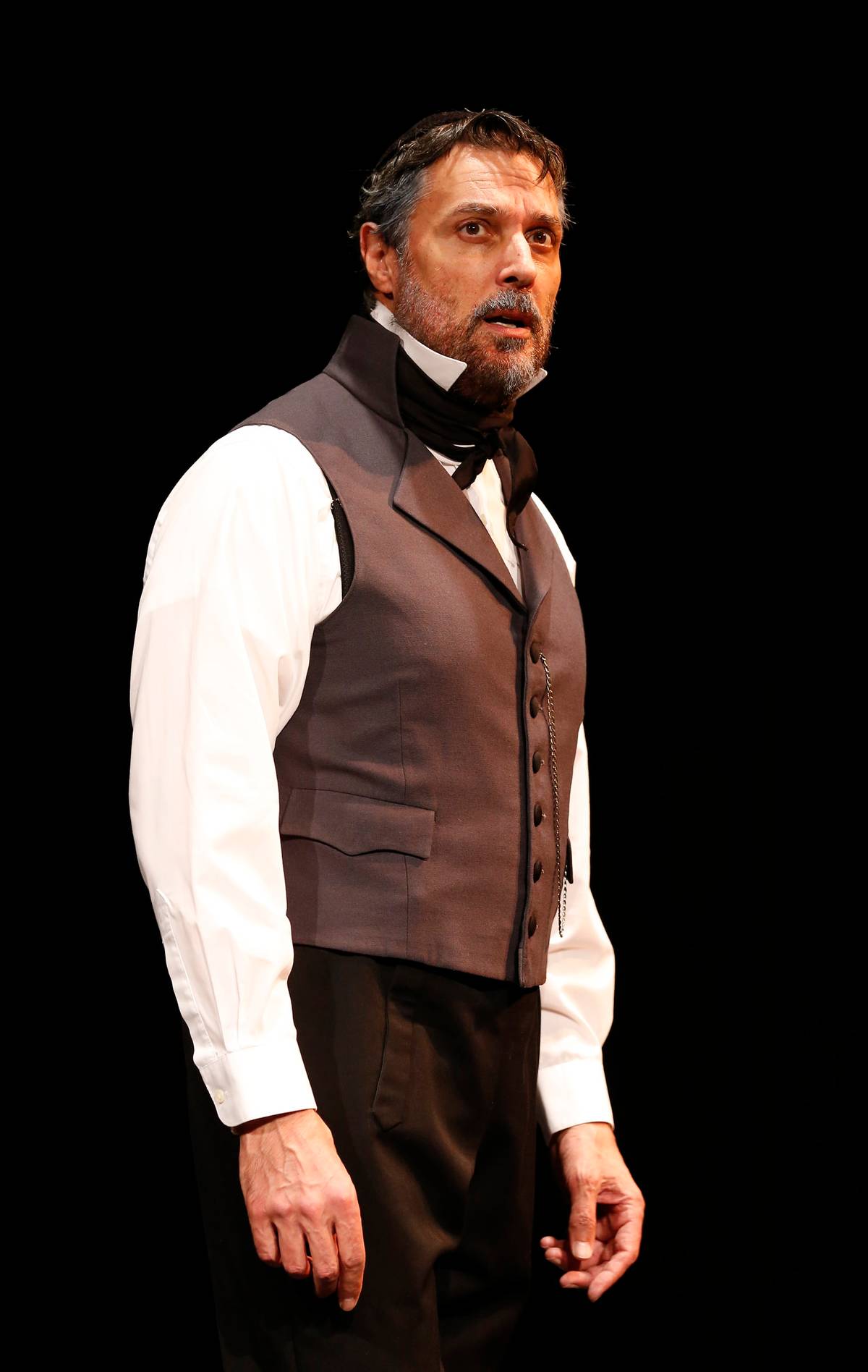

As the male lead, Robert Cuccioli plays patriarch Mayer Rothschild, a role that earned Hal Linden a Tony Award in 1971. Cuccioli, who actually played one of the sons in the 1990 production, removes much of the humor from the role that Linden so eloquently brought to it. In fact, this is one of the reasons the show putters at first, but by its emotional climax, the emotional payoff is all the sweeter when Cuccioli’s Mayer finally becomes vulnerable. The actor inevitably makes a fine transition of one man throughout his life. While this Gutele may speak her mind freely now, it’s still Mayer that’s in charge, directing his family to take great risks, even financially undermining Napoleon during the Emperor’s wars.

Comparisons between Rothschild & Sons to Fiddler are inevitable, and these come to a head in the respective patriarchs. After all, both musicals use the lead’s familial relationships as an exploration of Jewishness. But while Tevye sees his shtetl as a place of stability, Mayer Rothschild champs at the bit to leave the ghetto and join the larger world.

His hunger for financial gain is both a blessing and a curse to the show’s concept. These characters are ambitious businessmen who can’t remain sympathetic onstage if they seem greedy (plus, anti-Semitic conspiracy theories about the family persist), but pure altruists don’t make for compelling drama. The Rothschilds responded in part by making the outside world seem cruel and cartoonish, and while this re-imagining does that as well, it wisely focuses more on the family drama to carry the story: Mayer wants his sons to flourish, but fears losing control of his clan. When his son Nathan proposes lending money to Napoleon’s enemies in exchange for emancipating the Jews, Mayer has to confront whether teaching his children to take risks has backfired, or if he has grown fearful of change in his old age.

What also aids this family’s case is the score. While it’s not the stuff of crossover hits, there really are some good songs, and it’s a reminder that Bock and Harnick were no one-hit wonders. This songwriting team is having a renaissance, with revivals of Fiddler and their musical She Loves Me both coming to Broadway in the next few months.

One crucial bone to pick: In one moment in the show, a son cites scripture and points out that it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than a rich man to enter heaven. Yellen may be a Jewish writer, but it seems that he and everyone involved in this production forgot that that saying is actually from the New Testament.

That aside, in answer to the most important question, yes, Rothschild & Sons is a show worth performing in your synagogue’s basement.

Rating: 2.5 out of 4 stars

Gabriela Geselowitz is a writer and the former editor of Jewcy.com.