Why They Went: The Forgotten Story of the St. Augustine 17

55 years ago today, 16 American rabbis and one lay leader were arrested in a civil rights protest organized by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

“Did you know the rabbis?” I asked Rena Ayers, then 106 years young. “Oh sure,” she said, in her distinctly Southern drawl. We were sitting at her small kitchen table in Lincolnville, the historically black neighborhood of St. Augustine, Florida. Alongside us was Cora Tyson, who, at the age of 88, was as agile and alert as ever. Both women had been “house mothers” during the civil rights movement, hosting activists in their modest homes as they came through the city. Tyson had housed King; Ayers, I had been told, had hosted some of the rabbis.

Today, St. Augustine is known as a picturesque Florida vacation spot. Famed as the nation’s oldest city, it’s a quaint locale that was recently lauded by the New York Times for its “magic waters,” “moss-draped live oak trees,” and “butter pecan milkshakes.” But just decades ago, the city was the site of some of the civil rights movement’s most perilous protests.

It was here that a delegation of 16 Reform rabbis and one lay leader arrived, at the invitation of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., to stage a public protest—with the goal of submitting to arrest. Here, the rabbis were imprisoned overnight on June 18, 1964, in what was thought to be the largest mass arrest of rabbis in American history. From their cell, they wrote a joint manifesto, Why We Went, a profound document that expresses the rabbis’ political and religious aspirations.

Yet the story of the St. Augustine protests—and the role of its rabbinic participants—is often overlooked by civil rights histories, which focus on the renowned demonstrations in Montgomery and Birmingham. Similarly, Jewish accounts prioritize the movement’s iconic images—King and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel marching arm-in-arm in Selma—rather than the work of lesser-known activists.

I’d never learned about the St. Augustine protests and its rabbinic participants during my college courses in civil rights. But once I found out about them, my curiosity led me to the St. Johns County Jail—where the rabbis were held—and to the homes of veteran local activists.

I began shuttling across the country—from Los Angeles to Cincinnati to New York City—to track down the surviving rabbis and record their stories. Some of their reflections were sobering. “It was the first time in my life that I had to confront the fact that I might be facing death,” Rabbi Richard Levy told me in his office at Hebrew Union College in Los Angeles.

Like many moments of grassroots activism, the story of the rabbis’ arrest in St. Augustine has been carried and transmitted by the activists themselves, even as it has been largely forgotten by history. But their moment of moral witness deserves to be remembered.

This is their story.

* * *

On Tuesday, June 16, 1964, 55 years ago this week, Rabbi Israel “Sy” Dresner stood before his rabbinic colleagues at the 75th annual gathering of the Central Conference of American Rabbis (CCAR), the governing body of the Reform movement, to read a telegram from King. It asked the rabbis to join him in protest in St. Augustine, Florida, to bear “prophetic witness against the social evils of our time” and requested “that a delegation of the CCAR’s rabbis venture south,” emphasizing that “some 30 or so rabbis would make a tremendous impact on this community and the nation.” King’s telegram was terse; he had dictated it through the bars of his jail cell.

Dresner, one of King’s closest spiritual confidants, was a seasoned civil rights activist. In June 1961, he, along with 10 other clergy, had been arrested in Tallahassee, Florida, for attempting to integrate a “whites only” restaurant. A year later, he was jailed in Albany, Georgia, for assembling to pray for civil rights in front of city hall, along with 75 other clergymen. His colleagues teasingly referred to him as a “mishuga shel davar,” a man crazy for one issue: civil rights.

Within hours, a delegation of 16 rabbis—representing close to 10 states and spanning a decade in age—was mobilized: Rabbis Eugene Borowitz, Balfour Brickner, Sy Dresner, Daniel Fogel, Jerrold Goldstein, Joel Goor, Joseph Herzog, Norman Hirsch, Leon Jick, Richard Levy, Eugene Lipman, Michael Robinson, B.T. Rubenstein, Murray Saltzman, Allen Secher, and Clyde T. Sills. Al Vorspan, the social action commissioner of the CCAR, and a moral voice of the Reform movement, also joined. The delegation received few details about their travels; a memo told the rabbis to “bring as little baggage as possible. A toothbrush will suffice.” Some left before they had the chance to tell their wives.

The rabbis’ willingness to volunteer on a moment’s notice reflected their deep sense of solidarity with King. King cherished and nurtured his ties with the Jewish community and drew inspiration from what he saw as a shared Judeo-Christian tradition. Earlier that month, King had accepted an honorary degree from the Jewish Theological Seminary, sponsored by Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel. As Vorspan told me, “with Dr. King, there was implicit trust, a profound bond of mutual respect.”

The following morning, at the opening session of the convention, Rabbi Samuel Soskin, chairman of CCAR’s Committee on Justice and Peace, interrupted the proceedings to announce the St. Augustine delegation. His announcement was met by a standing ovation among the 500 rabbis present. But he tempered the CCAR’s message of support with words of warning. “I will remind you men and women here that these men are going down with full knowledge that, perhaps, there may be violence, and … ken ger harget varen.” In Yiddish: They could be killed.

* * *

In June 1963, President John F. Kennedy introduced federal legislation that would ultimately become the Civil Rights Act of 1964, landmark legislation that ended segregation in public places and outlawed discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. Kennedy introduced the legislation in response to vicious protests in Birmingham, Alabama, where law enforcement set police dogs on young children and used fire hoses against unarmed protesters. Yet, congressional debate had drawn to a stalemate, as Southern congressmen attempted to filibuster the bill out of existence.

To jump-start the political process, King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the civil rights organization he presided over, sought to organize civil rights protests that would catalyze the passage of the pending bill. They decided to stage them in St. Augustine, a city whose race politics mirrored that of neighboring Georgia and Alabama and which held the continent’s earliest slave records. The city’s troubled racial past had come to the fore in 1963 in anticipation of the city’s quadricentennial. The Florida Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights described St. Augustine as a “segregated superbomb aimed at the heart of Florida’s economy and political integrity—the fuse is short.”

But the protests soon became bloody. During SCLC’s nightly marches, white segregationists threw bricks, firecrackers, and acid at protesters. King’s beach house was burned twice. Television networks and newspapers began hiring bodyguards to protect their reporters from the violence. The police department—which had unofficial ties to the Ku Klux Klan—did little to maintain law and order. As Andrew Young, SCLC’s executive director and a close confidant of King, commented at the time, “St. Augustine is really worse than Birmingham. It’s the worst I’ve ever seen.”

On June 11, 1964, King spent a night in jail, after he and other activists attempted to integrate a restaurant in the Monson Motor Lodge, a new hotel in mock-Spanish style that housed most of the city’s visiting cameramen and, as a result, was a focal point of civil rights protests. It was from his jail cell that King decided to call upon public figures to join him in St. Augustine to attract national attention to the local civil rights negotiations. Hearing that the CCAR was soon to hold their annual conference, King decided to call on its rabbinic members for their support.

* * *

The rabbis landed in St. Augustine at a particularly tense moment. Earlier that week, Gov. Ferris Bryant had ordered a complete militarization of the city. A 150-man “special police force” was amassed. Checkpoints were set up at city entrances and the downtown area was heavily policed. The rabbis’ driver warned them that they might be followed. Later that night, frightened and fatigued, they arrived at their final destination: the St. Augustine First Baptist Church.

As the rabbis entered the sanctuary, they were welcomed by a standing ovation accompanied by cheers of “Hallelujah!” Women sat fervently fanning themselves with paper mortuary fans, having waited for three hours in the baking Florida heat. Wearing a sports shirt and sweltering alongside his congregants, King greeted the rabbis as “Moses People” and gave a brief sermon in which he lauded them as descendants of the ancient Israelites who themselves had experienced redemption from servitude. King traced the world’s love of freedom and the American civil rights struggle back to Moses’ initial call to “Let my people go.” Now, he said, “these rabbis have come to stand by our side, to bear witness to our common convictions.”

After King’s introductions, he invited Dresner to speak. The rabbi, familiar with the rhetorical style of the Black Church, surprised his audience and peers with call-and-response preaching. “It is a struggle for all people,” Dresner told the congregation. “We Jews know what it is to suffer. We have learned that freedom is indivisible.” In his characteristically long-winded manner, Dresner continued to sermonize until, overwhelmed by the heat, some of his fellow rabbis muttered gnug (enough)!

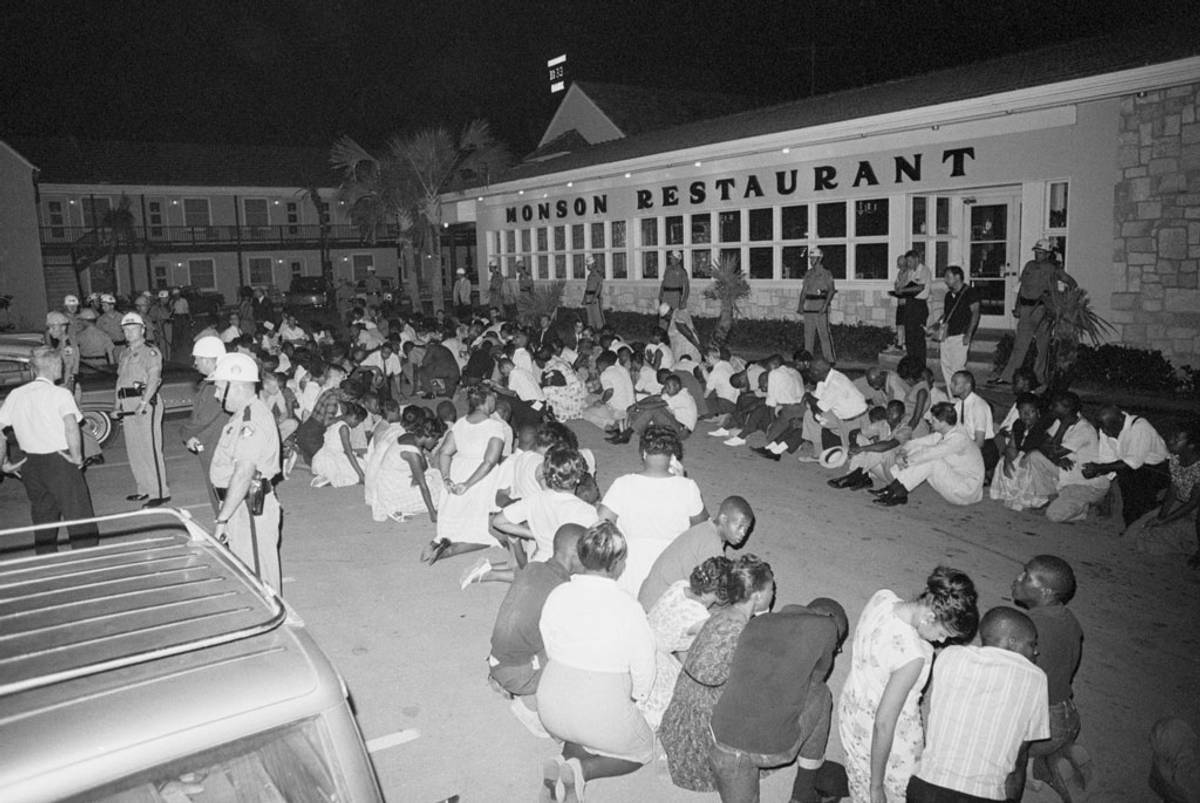

That night, the rabbinic delegation joined local protesters in their night march—almost 300 strong—through the white neighborhood of the city, along dimly lit, Mimosa-lined streets. The rabbis were paired with local protesters as they departed from the local Slave Market, a towering reminder of the city’s prejudiced past. They walked hand-in-hand into the night. As they marched, white citizens of St. Augustine lined the sidewalk screaming at the rabbis, “we don’t need you n*****-lovers!” and “you’re a bunch of communists!” Many held baseball bats, broken bottles, and bricks. The rabbis would later learn that a local policeman was found with a lead pipe up his sleeve. Close to midnight, the group arrived at the Monson and stopped to pray in its parking lot. Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, a founding member of SCLC, led them onto the driveway where he asked them to kneel for a short prayer service.

The rabbis eventually returned to their host families in Lincolnville. Many were shocked by the poverty they witnessed. Rabbi Herzog’s host family had nothing but a single milk carton of water and a can of vegetables in their refrigerator. They offered him and two other rabbis to sleep in the master bedroom, while they, a couple with four children, slept on the ground in the living room. Through their home-hospitality, the rabbis became painfully aware that although they had chosen to take this momentary risk, the families with whom they stayed would bear the true repercussions of their activism.

* * *

The following morning, Thursday, June 18, 1964, the rabbis gathered again at First Baptist for morning prayers, using the Bibles in the pews to recite the weekly Torah portion. When Rabbi Herzog gave a short sermon, King entered to listen. Afterwards, King briefed them on the day’s events. Before they departed, King read from Psalm 27, “The Lord is my light and my help; whom should I fear?” followed by a selection from the New Testament, “Blessed are those who suffer for righteousness sake.”

At noon, 15 of the rabbis joined 120 local protesters at the Monson. The rabbis again passed the menacing glances of crowds of white onlookers who lined the sidewalk. And once again, the group stopped in the parking lot to pray. Shuttlesworth and the rabbis formed a large prayer circle outside the Monson’s restaurant.

Immediately, James Brock, the motel’s manager and the president of the Florida Hotel and Motel Association, ran out of his restaurant to shoo the crowd away. Brock was ordinarily a self-assured businessman who bragged about the number of protesters arrested on his premises. But he was also a deacon in the local Baptist church, and he was angered by the rabbis’ religious demonstration. He shouted for them to leave and demanded Shuttlesworth’s arrest.

When a state trooper shoved Shuttlesworth, Rabbi Robinson stepped forward to block him. “Shall we continue our service?” he posed, inciting Brock to physically assault him and thrust him in the direction of four waiting police cars. As he did so, another rabbi took his place, until each had been detained. While they succumbed to arrest, the rabbis recited Psalm 23, “Yea though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death.” Later, Vorspan and Borowitz would be arrested, along with three black activists, for attempting to integrate Chimes, a restaurant down the block.

The arrests provided a perfect distraction. While the rabbis were being shoved into police cars, another car transporting five black demonstrators and two registered white guests arrived at the hotel. The group exited the car and jumped into the establishment’s segregated swimming pool. Brock grabbed a two-gallon jug of muriatic acid, a cleaning solution, and began pouring it into the water. An off-duty police officer dove into the pool in his civilian clothing to stop the demonstrators. Within minutes police officers were on the scene, using their clubs to lunge at the demonstrators and drag them out of the pool, where they were beaten and finally arrested. By that time, a crowd of 100 whites had gathered across the street and were chanting “Arrest them! Get out the dogs!”

King, who was also watching the incident from across the street, observed, “We are going to put the Monson out of business.”

* * *

Upon their arrival in St. Johns County Jail, the rabbis spent hours in an outdoor chicken coop under the burning sun. Slowly, they were each charged, and they welcomed each other inside the prison with the singing of Havenu Shalom Alecheim (We bring peace unto you), a song of greeting.

The locals, however, remained menacing. As Vorspan and Borowitz waited to be booked, they spoke with a man who appeared to be a civilian police officer standing inside the door of the jail; they would later find out that he was Hoss Manucy, head of Manucy’s Raiders, a group with connections to the Klan that patrolled the streets of the city to threaten integrationists. “Can’t figure out why you white n***** rabbis mixed yourself up in this thing,” he snickered. As Rabbi Levy waited to be booked, a local approached him and warned, “You know, sometimes the Klan comes into this space to practice.”

Once the rabbis had been admitted, they refused segregated cells. A guard entered and said, “You, Shuttlesworth, thatta way and you white n***** rabbis thatta way.” The rabbis formed a protective circle around Shuttlesworth and insisted that remaining together was their constitutional right. When county Sheriff L.O. Davis arrived on the scene, he furiously told the guards to bring in cattle prods. “In a moment,” Vorspan later wrote in Midstream magazine, “we became not only non-violent, but even non-resistant.” Feeling guilty for succumbing so quickly, the rabbis decided to stage a hunger strike—a decision made easier by the fact that they were offered only Gerber baby food to eat.

The rabbis were squeezed into a 15-by-20-foot jail cell, meant to hold six. The cell held a couple decrepit mattresses, a table, an open toilet, a sink, and a single shower head to keep them cool in the sweltering heat. Many of the rabbis stripped down to their underwear.

The rabbis were soon joined by the two white men who had jumped into the Monson’s pool, who arrived still in their swimsuits. The first, a Texan, was inspired to join the protests after meeting a concentration camp survivor. The second was a grandson of Justice George Shiras who had joined the Supreme Court’s majority opinion in Plessy v. Ferguson upholding “separate but equal” public facilities; he had committed his life to fighting for racial equality.

As they gathered to pray the evening service, the rabbis were met by another hostile visitor. Sunny Weinstein, the president of First Congregation Sons of Israel, St. Augustine’s oldest synagogue, arrived to berate the rabbis for their demonstration. Southern Jews had largely chosen to remain silent on civil rights, and the Jewish community in St. Augustine, consisting of less than 50 families, was no different. Many Southern Jews were merchants whose livelihoods were dependent on the business and good will of their white neighbors. And they were concerned for their own safety; anti-Semitic acts in the South had quadrupled during the civil rights era, with bombings of prominent synagogues in Atlanta, Nashville, Jacksonville, and Miami. Weinstein harshly interrupted the rabbis’ prayers: “I’m here to tell you so-called rabbis to shut up.” After their release, Rabbi Lipman responded with equal fervor. “Your hatred of everything Judaism teaches which is vital to life was so transparent,” he wrote. “I regret your actions, Mr. Weinstein. They are the only regret I have about my visit to St. Augustine.”

* * *

That night, awake in their sweltering cell, the rabbis penned a joint manifesto, later titled Why We Went, expressing the reasons that had motivated their activism. Many of the rabbis were self-conscious about being perceived as drive-by saviors, when, in reality, their activism paled in comparison to the suffering of the local black community. Others felt a deep need to communicate what they perceived to be so meaningful about their experience.

In the end, they decided to have Borowitz, then already a respected Reform theologian, take notes of their discussion. Borowitz wrote on the back of the only paper available—a mimeographed report of an assault by Ku Klux Klan members on blacks in St. Augustine. During their discourse, Borowitz gave each of the rabbis a slip of paper asking them to answer one question: Why they went. Borowitz then, by the light of a naked bulb, weaved the rabbis’ diverse responses into a unified letter. When Borowitz succumbed to sleep in the early hours of the morning, Vorspan finished editing the document, annotating Borowitz’s bright red cursive with his own blue chicken scratches. As Borowitz wrote Vorspan years later, “You were certainly, in many ways, [the document’s] spiritual father.”

The ensuing document lists the many reasons for the rabbis’ activism. “We came because we realized that injustice in St. Augustine, as anywhere else, diminishes the humanity of each of us.” “We came because we could not stand silently by our brother’s blood.” The rabbis were also motivated by the heavy burden of history. With the Holocaust only 20 years in the past, the rabbis saw their prison setting as “Jewishly familiar.” “We came because we know that second only to silence, the greatest danger to man is loss of faith in man’s capacity to act.”

The rabbis also viewed their activism through the prism of faith. “[W]e must confess in all humility that we did this as much in fulfillment of our faith and in response to inner need as in service to our Negro brothers. We came to stand with our brothers and in the process have learned more about ourselves and our God,” they wrote. “Each of us has in this experience become a little more the person, a bit more the rabbi he always hoped to be.”

The rabbis were also frank about the limitations of their service. In “the battle against racism, we have participated here in only a skirmish.” Nevertheless, they were optimistic about the contribution of non-violent protests like theirs to the civil rights cause. “[T]he total effect of all such demonstrations has created a Revolution; and the conscience of the nation has been aroused as never before. The Civil Rights Bill will become law and much more progress will be attained because this national conscience has been touched in this and other places in the struggle.”

They concluded with a traditional Jewish prayer: “Blessed art Thou, O Lord, who freest the captives.”

***

On Friday morning, the rabbis were bailed out by the NAACP for $900 each, $300 for each of three counts of trespass, conspiracy, and disturbance of the peace. In an unexpected gesture of good will, two local Jewish women sent kosher deli lunches to the SCLC headquarters for the rabbis to eat after their release. They hurried to catch their flights, to return to their congregations in time for the Sabbath.

News of the rabbis’ protest returned St. Augustine to the front page of every national newspaper. The front page headline of the New York Times read, “16 Rabbis Arrested as Pool Dive-In Sets Off St. Augustine Rights Clash.” The Department of Justice opened an investigation into the rabbis’ protest and arrest. In a letter of thanks to the CCAR, King wrote that the rabbis had done a “great deal to refocus national attention on the St. Augustine situation and … to project the moral issues involved.”

The news of the protests was also the feature story in the Washington Post, and highlighted the need for another featured story—the impending vote over the Civil Rights Bill in the Senate. Later that same day, exactly one year after Kennedy first introduced the bill, the Senate passed the Civil Rights Act by a vote of 73-27.

The response of the Reform leadership to the rabbis’ protest was predominantly positive. The CCAR, initially reticent in its support, now announced its “best wishes and our sense of gratitude.” The rabbis received overwhelming support from their respective congregations; even Rabbi Goldstein’s traditional synagogue in St. Paul, Minnesota, paid the entirety of his bail.

Yet, the Jewish response was not all encouraging. In the B’nei B’rith Messenger, Joseph Cummins, the editor and publisher, wrote a scathing editorial titled When the King Calls. In the article, he admonished the rabbis for “trading shule for pool” and bemoaned that “King gets better mileage out of some of our Rabbis than do our congregations.” In a letter responding to Cummins, Vorspan pointedly asked, “Is it inconceivable to you that a rabbi can be concerned about Jewish issues and civil rights issues?”

Many of the participating rabbis would continue to take part in civil rights demonstrations, as well as Vorspan who, with renewed resolve, assisted in Freedom Summer with another delegation of rabbis shortly thereafter. Brickner, Robinson, and Dresner would all devote their energies to the anti-war movement. Lipman and Levy would go on to serve as presidents of the CCAR, carrying their commitment to civil rights into the very organization that had once questioned their activism.

Other Jewish civil rights activists would not be as lucky—just two days after their return, two Jewish university students from New York, and a black union worker from Mississippi, would be murdered trying to register black voters in Freedom Summer.

As for St. Augustine, the city’s race relations continued to deteriorate. And, soon thereafter, the Monson itself fell victim to segregationists. The following month, after Brock served black customers testing the Civil Rights Act, a gallon jug of flammable liquid was tossed through a window of the hotel’s dining room. Two Molotov cocktails made with soft-drink bottles then ignited it. In reflecting on the protests in St. Augustine, King would admit, “some communities, like this one, had to bear the cross.” King believed that St. Augustine served a higher purpose: “Our nation responded in humble compliance to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 largely because of the movement … in our nation’s oldest city.”

* * *

Much has changed since that fateful summer, and yet, much remains the same.

Cora Tyson is now 96 years old. She still serves visitors the same iced tea she once gave King. But many of the rabbis, as well as Vorspan, have since passed. The largely unheralded story of their arrest, and the searing words of their prison letter, deserve to be remembered alongside the more celebrated acts and actors of the civil rights era. They are a reminder that change is made not only by those whose names are memorialized on monuments, but by everyday people of conscience. As Tyson told me, reflecting on her lifetime of activism, “We never thought we’d make history. We were just ordinary people.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Mitzi Steiner majored in American Studies and Human Rights at Barnard College. A graduate of Yale Law School, she currently works in New York City.