The Takeover

Progressive Jews are on the rise and they are not liberals

Ira L. Black/Corbis via Getty Images

Ira L. Black/Corbis via Getty Images

Ira L. Black/Corbis via Getty Images

For the past century, American Jews have consistently leaned to the left of most other Americans. Exceptions, like Orthodox Jews or recent immigrants, are dwarfed in size and influence by the majority of American Jews who identify as liberal and whose politics have shaped both the modern Democratic Party and the national political culture.

Today the preeminence of this Jewish-liberal alliance is threatened not from the right, but by the rising power and increasing population of Jewish progressives. While their numbers are still small relative to the overall community, left-wing progressive Jews are organized, vocal, engaged, and disproportionately influential on the national political scene. These progressive Jews are appreciably less engaged in Jewish life and with historic Jewish institutions than their more moderate liberal and centrist counterparts. Additionally, they lack the traditional pro-Israel sentiments that have been a hallmark of the Jewish American community for decades. As such, this growing bloc of progressive Jews may fundamentally alter the political priorities and preferences of the Jewish community going forward, with radically new views about social justice and Israel and notably anti-institutional and anti-religious inclinations.

The year 2018 may mark the start of a distinctive wave of progressive organizing and popular identification, both in the larger American society and among American Jews. It was 2018 when Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar, Ayanna Pressley, and Rashida Tlaib all ran for Congress and formed the progressive political bloc known as “the Squad.” That same year saw the revival of Jewish Currents, a magazine founded in 1946 and which, in its latest progressive incarnation, has sought to both preserve and transcend its origins as an organ of the Communist Party.

Since 2018, several new or growing Jewish communal groups also signal the rise of the progressives. Repair the World, Truah, Jewish Voice for Peace, Bend the Arc, and If Not Now have all benefited, despite their many ideological and stylistic differences, from a surge in Jewish ideological engagement on the left.

For religious traditionalists and cultural conservatives, this is a self-evidently disturbing phenomenon. Jewish progressives are seen as placing undue emphasis upon the tikkun olam—social justice—dimension of Jewish life, while downplaying other valued aspects of Jewish tradition. They may also be seen as unduly critical of Israel to the point of undermining the political legitimacy of the Jewish state.

But among Democrats the rise of the progressives is a more complicated phenomenon that is interpreted largely based on whether one sees progressivism as merely a more exaggerated and radicalized version of mainline liberal politics or an altogether different and oppositional ideology. The confusion about the meaning and implications of Jewish progressivism derives in part from conceptual ambiguity among progressives themselves. Like many well-established political terms—including conservative and liberal, Republican and Democrat—progressive has changed its meaning over time. It certainly means something different today than it did to Teddy Roosevelt, and his seeking to improve working conditions, advance health and safety standards and labor laws, promote women’s suffrage, counter government corruption, expand land conservation, and curb the power of corporations. Much the same can be said of followers of Wisconsin’s Robert La Follette, a contemporary of Roosevelt’s and a powerful member of Congress who ran a strong third-party campaign for president in 1924.

For many people today, “progressive” simply constitutes a preferred alternative to “liberal” and not much more. Some liberal Democrats identify themselves as “progressive,” using it as a near-synonym for “liberal.” The fact of the matter is that in the political climate of the present, the idea of being “progressive” means “different things to different people” and is used sloppily without precision or a set of coherent beliefs and policy preferences.

Today, the preeminence of the Jewish-liberal alliance is threatened not from the right but by the rising power and increasing population of Jewish progressives.

But for many, “progressive” does evoke distinctive attitudes and values, with there being two major types of progressives. One is the economic progressives, of whom Sen. Elizabeth Warren is a good example. They focus on closing the economic gaps between rich and poor, expanding social welfare programs, taxing the most affluent, and regulating corporate activity. For this brand of progressives, “social democrats” may be an apt term.

In contrast to the social democrats, a second group of progressives place their primary emphasis on cultural issues. One influential piece of recent research draws four points of genuine contrast between such “cultural progressives,” as the study terms this second category of progressives, and liberals. First, cultural progressives (though much the same can generally be said of economic progressives) place a premium on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs when allocating economic and social goods and rewards. Second, cultural progressives are highly critical of “cultural appropriation,” which, according to one definition, refers to “the adoption, usually without acknowledgment, of cultural identity markers from subcultures or minority communities into mainstream culture by people with a relatively privileged status.” Thirdly, “progressives supported publicly censuring those perceived to hold discriminatory views,” implying a greater inclination to participate in and favor “cancel culture.” And last, progressives tend to abjure incremental approaches to making change, reflecting in part their diminished valuation of established institutions.

Both cultural progressives and social democrats agree broadly on economic justice and on identity-race-gender justice, but each prioritizes one type of justice over the other.

Given increasing polarization in the U.S. and the rising influence of progressives writ large, it is unsurprising that an increasing number of American Jews now identify as politically progressive. The only estimate of American Jewish progressives comes from a recent national survey of American Jews sponsored by Keren Keshet in 2022-23. The survey finds that about 8% of American Jews identify as progressive, while 14% identify as very liberal, and another 25% as liberal. In all, 47% of American Jews are in the left camp (liberals and progressives), 34% are moderate, and 19% are conservative. The distribution from the 2020 Pew survey of Jewish Americans is quite similar—51% liberals, 32% moderates, and 16% conservatives.

The Keren Keshet data helpfully illustrate numerous differences between liberals and progressives. When asked about how much they worry about various specific political issues, compared to liberals, Jewish progressives express more concern about climate change and racism, but far less concern about crime. Asked about various political groups and leaders, notable differences are also found. Progressives are less favorably disposed toward Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer, while more enthusiastic about Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

These findings continue a long-standing trend of progressives being far more ideologically extreme, woke, and intolerant of difference compared to liberals. Across the nation, progressives are far more likely to want to silent dissent and censor open exchange, are notably more politically active than their liberal and conservative counterparts, and are far more likely to live in echo chambers where their views and voices are increasingly radicalized and divergent from the political center.

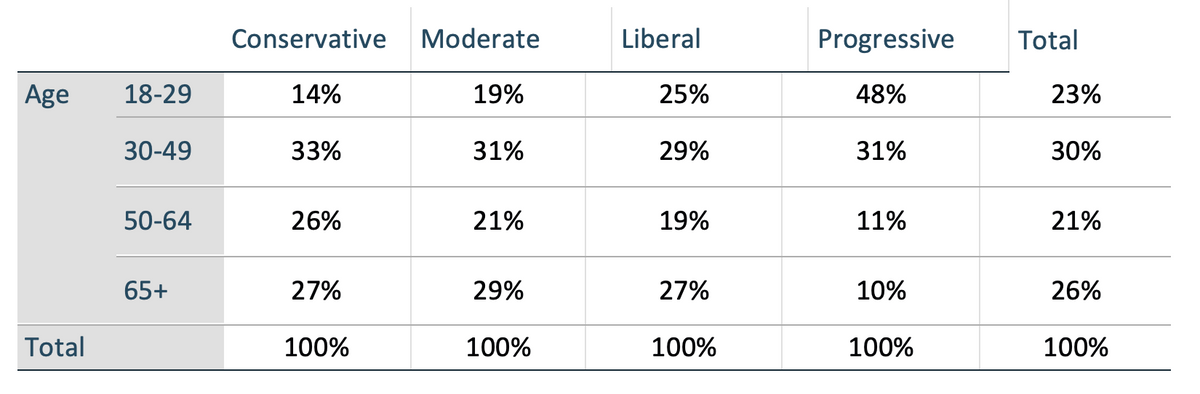

The Keren Keshet data reveal some further findings on Jews resembling the larger, national trends. As shown in Table 1, Jewish progressives are much younger than Jewish liberals. There are about twice as many progressives who are between the ages of 18 and 29 as there are liberals (48% vs. 25%) who, in turn, are almost twice as likely as conservatives (14%) to fall into that young age range. Simply put, the further left, the younger; the younger, the further left. And as a proportion of the population, of those aged between 18 and 29, 18% are progressive. That figure means that the progressives are twice as numerous among the youngest adults as among those 30-49, and four times as many among those 50-plus, implying that the progressive proportion of the Jewish American population has doubled every 20 years or so.

Table 1: Age by Political Identity

The surge in progressive identity is indeed a relatively recent phenomenon—a trend that has taken place during the last decade. Likewise, assuming these political identities hold over time, progressives are poised to become even more influential as their large numbers age and mature.

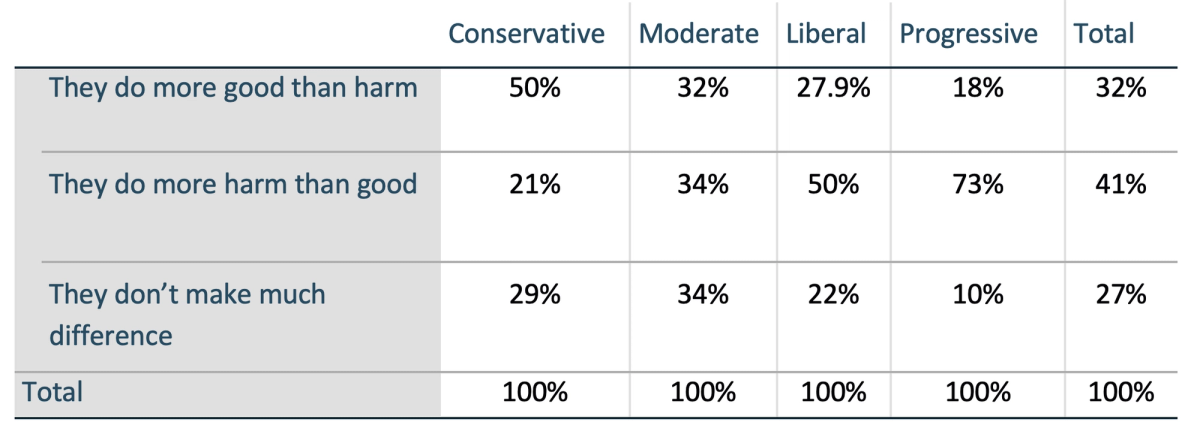

Though progressive Jews often try to connect their political stances to beliefs in the Jewish religious or cultural tradition, progressives were the most anti-religious group in the Keren Keshet survey results.The survey asked, “Considering everything, what impact do you feel religious organizations have on American society?” By more than 2:1, conservatives felt religious institutions do more good than harm, as opposed to doing more harm than good (50% vs. 21%). And by almost 2:1, liberals felt the opposite (28% vs. 50%). A mere 18% of progressives believe that religious institutions have a positive impact on society.

Table 2: ‘Considering everything, what impact do you feel religious organizations have on American society?’ by Political Identity

In line with their dim view of religious organizations in general, of all the political identity groups, progressives are the least likely to identify with any Jewish denomination. Most Jewish progressives (58%) have no denominational identity, compared with 43% among liberals, and just 36% for conservatives. The aversion to denominational identity even extends to Reform identity. For both liberals and progressives, of the denominational choices—aside from “no denomination”—Reform is the most favored denominational choice. But, that said, it is substantially more popular among liberals than among progressives (33% vs. 20%).

Table 3: Jewish Denominational Identity by Political Identity

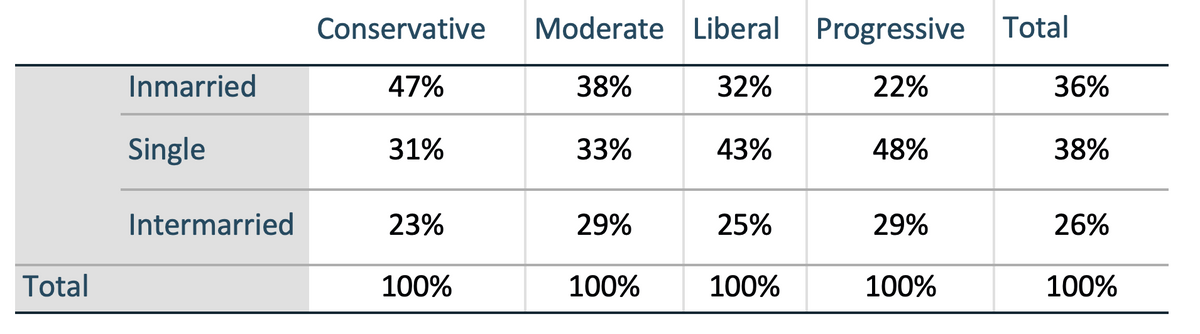

The progressives’ detachment from religion in general and conventional Judaism in particular is reflected in their marital patterns. People become more religiously engaged with marriage (and even more so with parenthood). It is no surprise that almost half of progressives (48%) are single, somewhat more than liberals (43%), and much more than moderates (33%) and conservatives (31%). If marriage brings people closer to their faith, this statistic only reinforces the movement away from religious life. In fact, as Table 4 demonstrates, progressives are characterized by low rates of in-marriage within the Jewish community—lower even than among liberals. Thus, the marriage patterns of progressives are one good reason to anticipate relatively low levels of conventional Jewish engagement, compared with the other political groups.

Table 4: Couple Status by Political Identity

As we have seen, progressives are indeed growing in number among American Jews in line with their disproportionate numbers among younger Americans. They are distinctive in numerous ways, among them: their attitudes toward religion’s role in society, their denominational distribution, and their marriage patterns. All of these help generate a very distinctive pattern of Jewish engagement among Jewish progressives, differentiating them not only from Jews at large, but from liberal Jews as well. It also is in line with larger ideological sorting where younger Americans and younger Jews are far less religious and supportive of traditional institutions—institutions which traditionally help anchor social and community relationships and promote mental health along with providing support in our nation’s loneliness crisis.

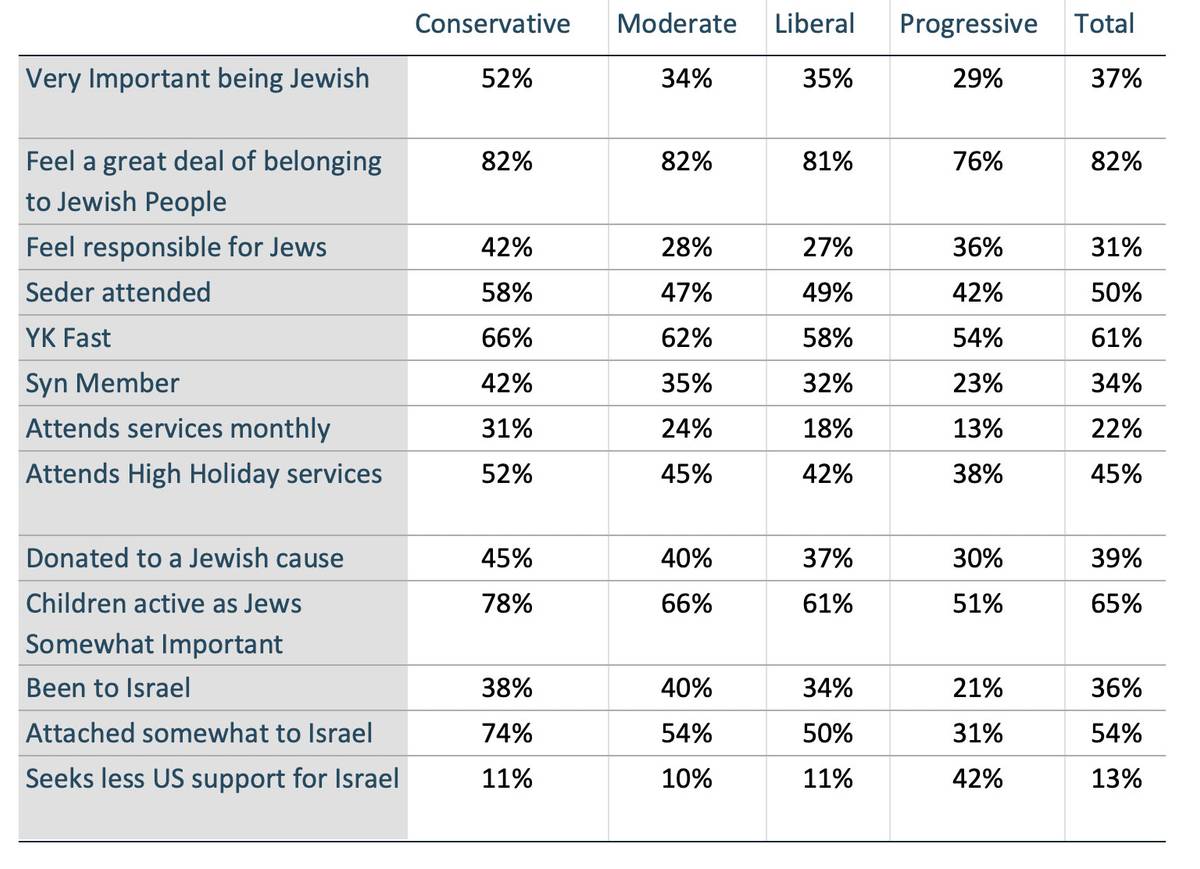

How do Jewish progressives compare with other political blocs on Jewish engagement? In short, with respect to their Jewish identity, progressives trail behind all their ideological counterparts. To take one example, only 30% of progressive Jews donate to Jewish causes, compared to 45% of conservatives, 40% of moderates, and 37% of liberals. They even trail liberals noticeably with respect to: feeling that being Jewish is very important; attending a Passover Seder; belonging to a synagogue; attending services monthly; and feeling that their children should be active as Jews. These are certainly not areas of Jewish engagement where progressives excel.

Looking over all these measures, progressives are generally in last place. They trail liberals by noticeable gaps, almost always by greater amounts than liberals trail moderates (if and when they do). Jewish engagement levels decline from political right to political left.

Table 5: Jewish Identity Indicators by Political Identity

There is one area, however, where progressives are especially low scoring: their connection with Israel. As compared with liberals, progressives are less likely to have visited Israel (21% vs. 34%). They are also less likely to feel at least somewhat emotionally attached to Israel, and by quite a large gap—31% vs 50%. The largest difference on Jewish engagement items between progressives and all the others is with respect to saying that “The U.S. is too supportive of Israel”—an answer given by 42% of progressives vs. 10%-11% of the other political groups.

While progressives trail all the other political identity groups in most forms of conventional Jewish engagement, they do exhibit many signs of Jewish identification strength. Illustratively, three-quarters feel a sense of belonging to the Jewish people, most do fast Yom Kippur, and 23% belong to synagogues as compared with 35% of all others. In terms of Jewish engagement levels, then, progressives may be “down,” but they’re not “out.”

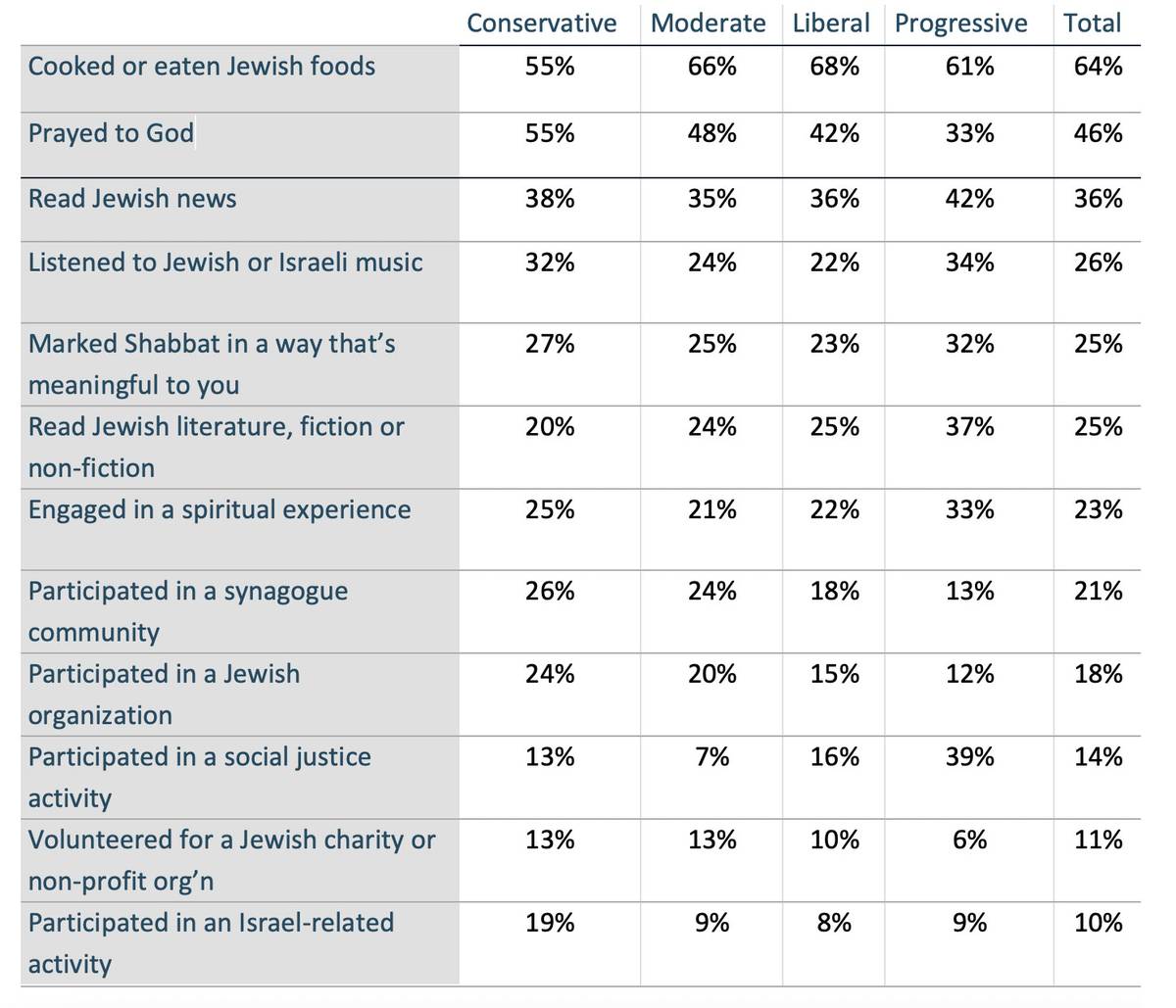

And not only do progressives keep pace in some areas, but, with respect to less conventional Jewish activities, progressives actually outscore most others. They read Jewish news and literature more than others. They engage in spiritual experiences, listen to Jewish music, and mark Shabbat, albeit, in all likelihood outside the synagogue. As one might expect, they are “off the charts” with respect to having participated in a social justice activity in the last three months (39% vs. 16% for liberals).

Table 6: Alternative Jewish Activities by Political Identity

The distinctive Jewish engagement patterns for progressives—low scores on conventional measures of Jewish engagement, several of which signify collective activity, alongside high levels in several other areas that are less conventional and more personal—speak to a long-standing question in the study of American Jewry and its patterns of change. For decades, social scientists and community leaders have divided into two camps over some fundamental questions regarding Jewish social change and its implications for the future. In one camp are the “assimilationists.” They interpret the major trends in American Jewry as pointing to diminished engagement in Jewish life and fewer points of distinction between Jews and others. The other camp, dubbed “transformationists,” construes matters differently. They certainly see change and the diminution of forms of Jewish engagement. But they also see the rise of alternative and innovative ways of expressing Jewish ties and commitment.

The rise of Jewish progressives and their patterns of Jewish engagement lends credence to both perspectives. Certainly, as a group, progressives exhibit many signs of assimilation, with far lower rates on a wide variety of Jewish identity indicators. At the same time, they do score higher on several personal measures.

Almost a quarter century ago, a monograph on changing patterns of Jewish identity in America, The Jew Within, observed a turn away from more collective and communal ways of being Jewish and toward expressions that are more private and personal, if not highly idiosyncratic. Thus, one could anticipate declines in such measures as synagogue affiliation, organizational membership, Israel attachment, charitable giving, and other ways in which Jews traditionally act together and express group solidarity. In contrast, other expressions—the kind done on one’s own or in the home such as lighting Shabbat candles and performing particular mitzvot that do not require a community—should hold steady or maybe even increase. Indeed, the decline of the collective and the rise of the personal has arguably fairly well-characterized trends in Jewish identification over recent decades. And they speak to many of the differences between progressive Jews and liberals, moderates, and certainly conservatives.

The key takeaway from the current research is that progressives constitute a political camp distinct from liberals. While progressives are less engaged in almost all aspects of conventional Jewish life, they are more attuned than those with other political identities to Jewish cultural engagement. They are more distant than others from collective- and institution-based Jewish action and they are more engaged in personal Jewish activities undertaken at home or in “third spaces” (outside the home and workplace). Among their most distinctive features is that Jewish progressives are very distant from Israel—even to the point of expressing what some would see as anti-Israel views.

The patterns of Jewish engagement implied by the progressives are noteworthy. For practitioners and policymakers, they suggest an increased emphasis on encouraging the music-news-literature-Shabbat Jewish culture—on its own terms, not as a way of promoting the synagogue-UJA-AIPAC version that progressives and others appear to find alienating.

With increasing numbers of American Jews assuming the progressive label, and with developments in Israel proceeding as they have been recently, the difficulties of navigating the politics of Jews and Jewish life will only intensify. For progressives, Israel is on the wrong side of the narrative and even of history, becoming a key test of ideological purity and commitment. Being highly critical if not overtly hostile toward Israel is not simply one stance among others for Jewish progressives: It is a defining feature of their political identity.

Looking forward, the progressive tendencies that have emerged in schools, workplaces, and the public sphere over the past decade may be slowing. While progressives may be well-organized, and be generating a lot of noise, they are only a small minority in the overall population and surveys are regularly showing that Americans are embracing conservative economic and social positions at levels that have not been seen in more than a decade. Support for progressive hot button issues like Black Lives Matter has widely dropped and more Americans disapprove than approve of colleges considering factors like race and ethnicity in admissions decisions.

Yet, despite the overall course correction, it’s clear that Jewish progressives continue to exert an outsize influence over the mainstream liberal establishment. Moreover, there is little question that the relative influence and numbers of Jews in powerful roles from cultural institutions to higher education and public affairs are in steep decline, and Jewish progressives today are leading the entire Jewish community down that path. This is not an inevitability and the relative numbers here are small, so the rest of the Jewish community—liberals, moderates, and conservatives—must engage now if they do not wish to see their collective power eroded further. This is a textbook example of tyranny of the minority, and like mainstream American politics being dominated by the extremes rather than the large and moderate center. If that center can reassert itself remains an open question.

Samuel J. Abrams is a professor of politics at Sarah Lawrence College and a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.