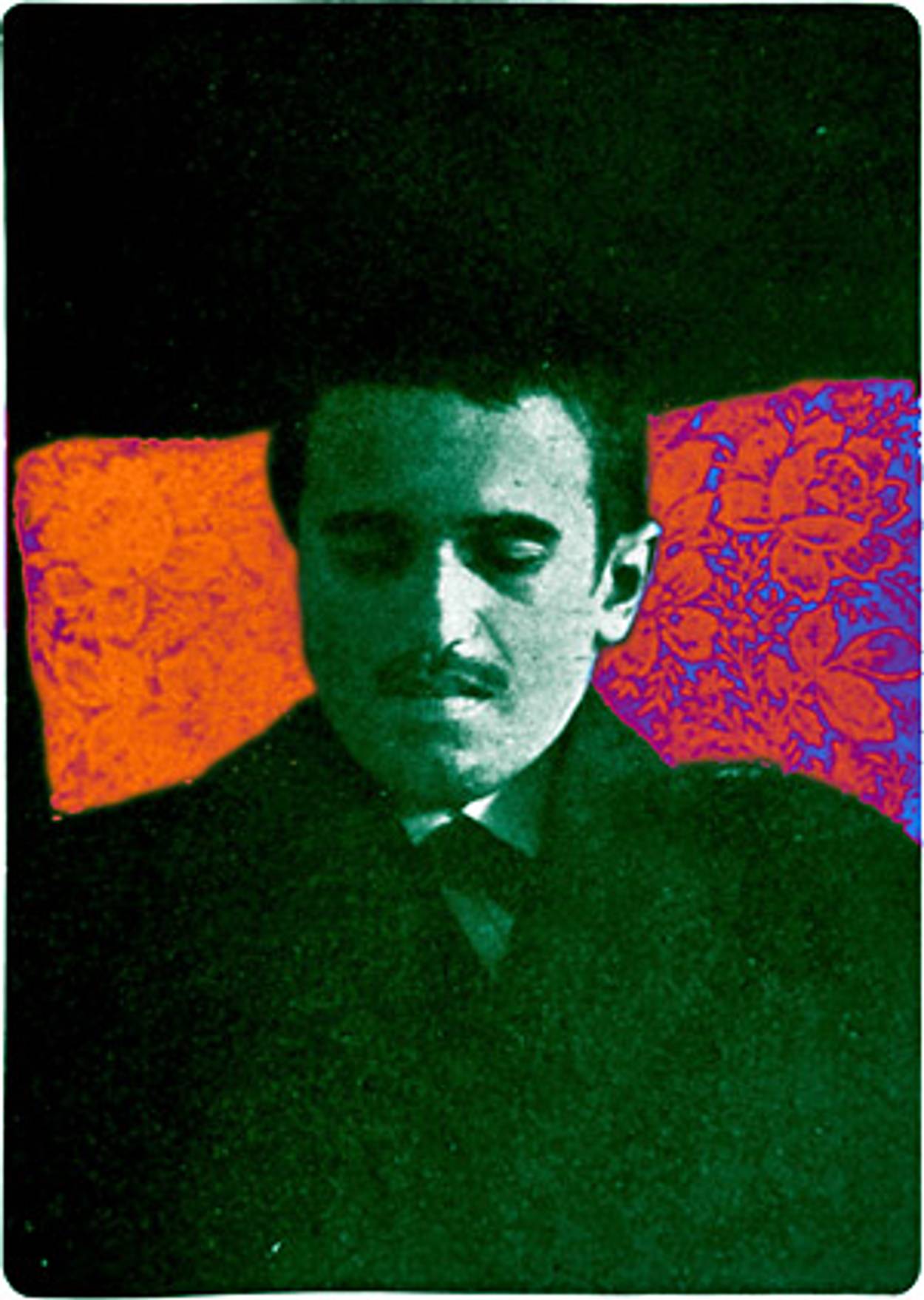

Was This Man a Genius?

The twisted mind of Otto Weininger

In Otto Weininger’s Sex and Character—published four months before his suicide, at twenty-three, in 1903—a brilliant mind comes unmoored. Based on a grotesque premise, the book reasoned shoddily to monstrous conclusions. It distinguished itself as notably anti-Semitic in fin-de-siècle Vienna, a setting in which the distinction wasn’t easy to earn; and it is perhaps the most misogynistic book written in any language in the history of the world. It embraced the Wagnerian opposition of the heroic Aryan to the materialistic Jew; enthusiastically cited Houston Stewart Chamberlain, the theorist of racial degeneration read so avidly by Hitler; and ended by endorsing the voluntary self-extinction of the human race.

A book like this survives, to the extent that it does (a new English translation—the first since 1906—by Ladislaus Lob was issued by Indiana University Press in 2005, with a preface declaring it “The Book That Won’t Go Away”), principally as a reminder of the perverted thinking that was midwife to an age of atrocity. Fin-de-siècle Vienna, the place where, as the historian Norman Stone puts it, “most of the twentieth-century intellectual world was invented,” gave us psychoanalysis, analytic philosophy, atonal music, and architectural modernism, among other attainments, but it also bequeathed a darker legacy. While it was nurturing Ludwig Wittgenstein, scion of a family of wealthy and accomplished secular Jews, in one part of the city, a vastly less fortunate and gifted young man, squirreled away in a men’s rooming house—Adolf Hitler—was failing in his bid to earn admission to the academy of art, and schooling himself in the doctrines of race war and Aryan superiority flourishing in the intellectual undergrowth of that city (and, alas, not only there, and not only in that city).

But Weininger’s strange book, the only one he published in his short life, survives not just as a primary source in the history of political and psychosexual pathology, but also in the history of thought and art. It straddled the young Hitler’s Vienna and the Vienna of Wittgenstein, Freud, Oskar Kokoschka, Adolf Loos, Gustav Mahler, and Clemens Krauss in an utterly eccentric way that casts an oblique light on both of the city’s legacies.

For one thing, Wittgenstein himself credited Weininger as one of the ten thinkers who decisively influenced him—exactly how remains a matter of scholarly speculation and dispute. (In a letter to G.E. Moore, Wittgenstein remarked that “he was fantastic, but he was great and fantastic,” going on to assert that “roughly speaking, if you just add a ‘~’ to the whole book it says an important truth.”) Wittgenstein was far from alone in his admiration. Many of the canonical figures of the heroic period of early Modernism—Karl Kraus, August Strindberg, Hermann Broch, James Joyce, and Franz Kafka—read and discussed him and, in ways both apparent and obscure (few of them uncritically embraced his assertions about women or Jews), were influenced by him. There was something remarkable about the book that some of the best minds of his generation were content to call genius. His writing, Elias Canetti recorded in his diary of Vienna in the 1920s, “cropped up in every discussion.” Ford Madox Ford described the “immense international vogue” the book experienced after Weininger’s death thusly: “One began to hear singular mutterings amongst men. Even in the United States where men never talk about women, certain whispers might be heard. The idea was that a new gospel had appeared.”

The new gospel purported to resolve for the first time—and for all time—the “Woman Question,” by means of an investigation into the deep structure of femininity and masculinity—it was an inquiry into not women but Woman. It is a sprawling, unstable admixture of scientific and pseudoscientific theorizing, cultural polemic, and philosophical argument that imposes a paranoid coherence on its breathtakingly disparate elements. Even while heaping rhetorical abuse upon women and Jews, Weininger argues explicitly against any infringement of their rights. To understand the weird fascination the book exerted on its readers, one must appreciate it for all that it was: an impassioned defense of the autonomous self against the forces that would turn it into a thing to be manipulated, an impossibly idealistic assertion of neo-Kantian ethics, a glimpse into one tortured young man’s psychosexual panic, and a sounding board for an inflamed epoch’s sexual and racial obsessions. Though Weininger’s view of women is practically incomprehensible to those of us raised in the postfeminist present, it merely advanced with fanatical rigidity a view that permeated his age, expressed in the violent misogyny appearing in the paintings of Alfred Kubin, Egon Schiele, and Oscar Kokoschka, among others, which is vividly summoned up by the title of Kokoschka’s avant-garde play Murder, Hope of Woman.

Sex and Character begins with an argument about method, assailing the experimental psychology of the day—which had famously declared, in the words of its leading exponent, Ernst Mach, that the “self was beyond salvage.” The autonomous and unified subject of liberal political philosophy had come under assault; following the philosophical skepticism of David Hume, the experimental psychologists saw the mind as a mere bundle of sensations. They eschewed introspection as a valid form of investigation, and restricted research to what could be measured in a laboratory. Psychology, then, as Weininger puts it, “completely fails to reach those problems normally described as eminently psychological, the analysis of murder, of friendship, of loneliness, etc.” In place of this impoverished account of the self, Weininger argued, we needed a new “characterology,” which would inquire into the stable and unique source of individuality, into that “something that reveals itself in every thought and every feeling.”

Weininger rooted his concept of the self in Kant’s transcendental, suprasensible “intelligible” subject, whose existence could never be demonstrated empirically, but only deduced. This self makes our perception of empirical reality possible. For how could we conceive of time if we were merely caught up in the flux of sensation from isolated moment to isolated moment? Some part of us must partake of eternity in order for us to know eternity, and it was, Weininger said, this suprasensory self that was responsible for all of the highest expressions of the human spirit. “The desire for value expresses itself in the general striving to emancipate things from time,” he wrote. The genius is the person who remembers everything because he is capable of endowing every moment of his life with meaning.

It is this intelligible self in each of us that gives humanity its special moral significance. Kant’s “categorical imperative” enjoins us to treat all others as ends in themselves rather than means to other ends. The categorical imperative defined for Weininger the curious vision of utopia articulated in his book: a world in which people engage in mutually respectful relationships that inspire individual genius and spiritual perfection. It also defined the negative utopia that Weininger saw emerging all around him:

Although in a later chapter Weininger concedes that women are not “animals or plants,” but in fact “human beings,” they qualify for this distinction only in the most rudimentary, basely biological way.

a modern world in which people were becoming mere cogs in a gigantic machine, using each other for their own basely material ends, and negating the very existence of a higher world. Our materialistic, mechanistic science was but one of the many faces this creeping degeneration wore. Our glorification of sex was another.

Throughout Weininger’s account of the intelligible self and of genius, he continues to denigrate women in a way that feels compulsive and almost beside the point, noting that if men are capable of conscious thought, women are capable only of calculating immediate material advantage, and that if men are capable of spiritual aspiration, women are capable of mimicking—expertly—whatever men present to them as the proper values to emulate. Thus far, we remain within the context of the misogyny of the age—the misogyny of Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, and a thousand after-dinner boors.

It is when Weininger turns fully to the subject of Woman that the book begins its long slide into extremism. He proclaims Woman to be nullity itself: incapable of reason, creativity, or spiritual aspiration; sexually insatiable (“under the spell of the phallus”); psychologically incoherent, desiring nothing more than her own subordination to man—“a hollow vessel covered for a while in makeup and whitewash.” Although in a later chapter Weininger concedes that women are not “animals or plants,” but in fact “human beings,” they qualify for this distinction only in the most rudimentary, basely biological way. In a passage devoted to acknowledging the “meanness and inanity” that may appear in individual men, he nonetheless concludes that “the most superior woman is still infinitely inferior to the most inferior men.”

Weininger’s misogyny is eccentric. His extremism leads him, at times, to sound rather like a radical feminist. He will have nothing to do with the sentimental veneration that imprisons women while pretending they are more virtuous than men. He wants to debunk what he sees as the great lie written into the traditional narratives structuring relationships between men and women. Love itself is a form of imprisonment. And “all eroticism, even the most sublime, remains a threefold immorality: selfish intolerance for the real empirical women, who is merely used as a means to an end . . . and who is therefore denied an independent life of her own.”

Weininger closes his long inquiry into the “Nature of Woman and Her Purpose in the Universe” by laying the responsibility for the moral condition of women on men: “Man must redeem himself from sexuality in order to redeem Woman.” Weininger acknowledges that this will mean the extinction of the human race. It is a small price to pay for the emancipation of woman, and the perfection of humanity.

Tacked onto this exhaustive inquiry, the weird fascination of which is impossible to convey in any quotation or series of quotations, Weininger wrote a single chapter that would help to define the category in which he is, along with “crazed misogynist,” best remembered—that of the self-hating Jew. For Weininger was the son of a solidly middle-class Jewish goldsmith much admired for his knowledge of his craft. Secular in orientation, anti-Semitic in his opinions, Leopold Weininger nonetheless, according to his daughter, Rosa, “thought as a Jew and was angry when Otto wrote against Judaism.” Like other sons of the newly emergent Jewish middle class, Weininger went to a private high school, where he learned multiple languages and attended to self-cultivation with an intensity that is scarcely conceivable today. There, he came upon a dawning conviction that has afflicted hormonal adolescent men throughout history: that he was a genius. This subject would absorb much of his attention in Sex and Character, in which he defines “genius” as a capacity for universal empathy with other men and with the universe as a whole. The genius becomes the “microcosm” able to absorb and reflect everything he encounters.

Weininger was a tortured soul who “lived in complete isolation” with his books, according to his father, and held himself aloof from the pursuit of sex and drinking that characterized the social lives of his classmates at the University of Vienna. His letters refer to his inability to experience pleasure or love, and an overpowering sense of his own moral corruption. There is no evidence that he ever had sex with a woman, and no conclusive proof that he was either sexually abused as a child, as David Abrahamsen speculated in his 1946 book The Mind and Death of a Genius, or homosexual, as others have speculated. Chandak Sengoopta’s excellent 2000 monograph Otto Weininger: Sex, Science, and Self in Imperial Vienna includes a letter from Weininger to his closest friend in which he reports success in administering male hormones for the purpose of converting a homosexual “patient” who was, in fact, “already preparing for his first coitus!” Sengoopta asserted that it was “strongly likely” that the “patient” was Weininger himself.

In 1902, Weininger wrote a dissertation on sexual characteristics that his professors admired, but not without misgivings. Weininger’s assertions on women “could not be described as anything other than fantastical,” one of his advisors wrote. (The same professor would later call the latter half of Sex and Character “shocking and repulsive.”)

Weininger openly acknowledged that he was himself “of Jewish ancestry,” and then went on to argue that Jews, like women, are “soulless people” who lack intelligible selves.

The dissertation would eventually become Sex and Character, but not before failing to earn the endorsement of Sigmund Freud, who nonetheless described Weininger as a striking personality “with a touch of genius.”

Soon after completing his dissertation, Weininger converted to Protestantism—doing himself no worldly favors in that Roman Catholic capital, but instead announcing his commitment to the austere creed of Northern Germany, and the religion of his hero, Immanuel Kant. But in a footnote to his infamous chapter on Judaism, Weininger openly acknowledged that he was himself “of Jewish ancestry,” and then went on to argue that Jews, like women, are “soulless people” who lack intelligible selves. But he does this in a characteristically eccentric way that has nothing to do with the eliminationist anti-Semitism of the Nazis, and everything to do with his own anguished wrestling with his own identity.

“From now on,” Weininger wrote, “when I speak of the Jew I mean neither a specific individual nor a collective, but every human being as such, insofar as he participates in the Platonic idea of Judaism.” The Jew is “relatively amoral, never very good and never very bad,” and the “opposite pole of the aristocrat,” for whom “the strictest observation of the boundaries between human beings” is the guiding principle of conduct. Yet the Jew is also “the born communist and always wants community.” At the same time, the Jew is the spirit of irony and debunking, wishing to denude the world of mystery, and strip away the spirit from the material world. Never truly revolutionary, but always subversive, “he is an absolute ironist, like—and here I can only name a Jew—like Heinrich Heine.” Capable of adapting himself to all situations, he never really possesses an inner being.

Weininger goes on:

It is like a condition before being, an eternal wandering back and forth before the gate of reality. There is nothing with which the Jew can truly identify, no cause for which he can risk his life unreservedly. What the Jew lacks is not the zealot but the zeal, because anything undivided, anything whole, is alien to him. It is the simplicity of belief that he lacks and it is because he lacks this simplicity and stands for nothing positive that he seems to be more intelligent than the Aryan and is supple enough to wriggle out of any oppression. Inner ambiguity, I repeat, is absolutely Jewish, simplicity is absolutely un-Jewish.

Jewishness is thus, for Weininger, as it was for many others, a spiritual condition more or less identical with modernity itself. (And certainly not, as it was for the most virulent anti-Semites, either a malevolent or a uniquely powerful force ruling the world from the shadows.) It is also roughly analogous to the diagnosis of the Jewish condition advanced by the pioneering Zionists, who dreamed of a Jew restored to psychic health and vigorous manhood by a renewed relationship to the land. Weininger rejects Zionism as the solution to the Jewish question, but curiously he retains it as an unreachable ideal. “The Jews would have to overcome Judaism before they could be ripe for Zionism.” This cannot be done collectively, Weininger argues: “Every single Jew must seek to answer it for his own person.” But by posing the greatest obstacle, Judaism also occasions the highest possibilities. Thus, “Christ was the greatest human being because he overcame the greatest adversity,” as “the only Jew who has ever succeeded in defeating Judaism.”

This struggle against the Jew in each of us was, for Weininger, clearly a battle the culture at large was losing:

Our age is not only the most Jewish, but also the most effeminate of all ages . . . an age of the most credulous anarchism, an age without any appreciation of the state and law . . . an age of the shallowest of all imaginable interpretations of history (historical materialism), an age of capitalism and Marxism, an age for which history, life, science, everything, has become nothing but economics and technology; an age that has declared genius to be a form of madness, but which no longer has one great artist or one great philosopher; an age that is most devoid of originality, but which chase most frantically after originality; an age that has replaced the idea of virginity with the cult of the demivierge. This age also has the distinction of being the first to have not only affirmed and worshipped sexual intercourse, but to have practically made it a duty, not as a way of achieving oblivion, as the Romans and Greeks did in their bacchanals, but in order to find itself and to give its own dreariness a meaning.

One recognizes in this peevish rant the intransigence of youth. In differing forms Weininger’s concerns were the concerns of anti-modernists of every persuasion, including some of our most admired writers. But they come together in Weininger with a rigidity and literalism, an absence of humor or detachment that marks his work as that of a callow, sheltered, and disturbed personality. Weininger might conceivably have worked through his issues over time, had he taken Freud’s advice and spent another ten years gathering data for his wild assertions, perhaps abandoning them in the process. Weininger’s propositions tell us nothing useful or true; instead they enact for us a drama that is of continuing significance to a world in which bright young men—traumatized by sex, infatuated with piety, and obsessed with Jews—continue to try to live in opposition to the age by dreaming of apocalypse.

The fin-de-siècle anti-modernists feared a world from which all nobility and heroism would be banished, and in which the individual would be swallowed up by a technological mass society. Their fears were not without basis. The more reckless among them, who substituted crude symbols, like the Woman or the Jew, for concrete analysis of large social processes, made more than an intellectual error. They helped to make the earth, for a time, into hell. Weininger became the microcosm of his age, but not in the way he intended.

Wesley Yang is the author of The Souls of Yellow Folk.

Wesley Yang is the author of The Souls of Yellow Folk.