Unsubscribe From Everything

You may think you’re not worth spying on. But to our government, we’re all terrorists now.

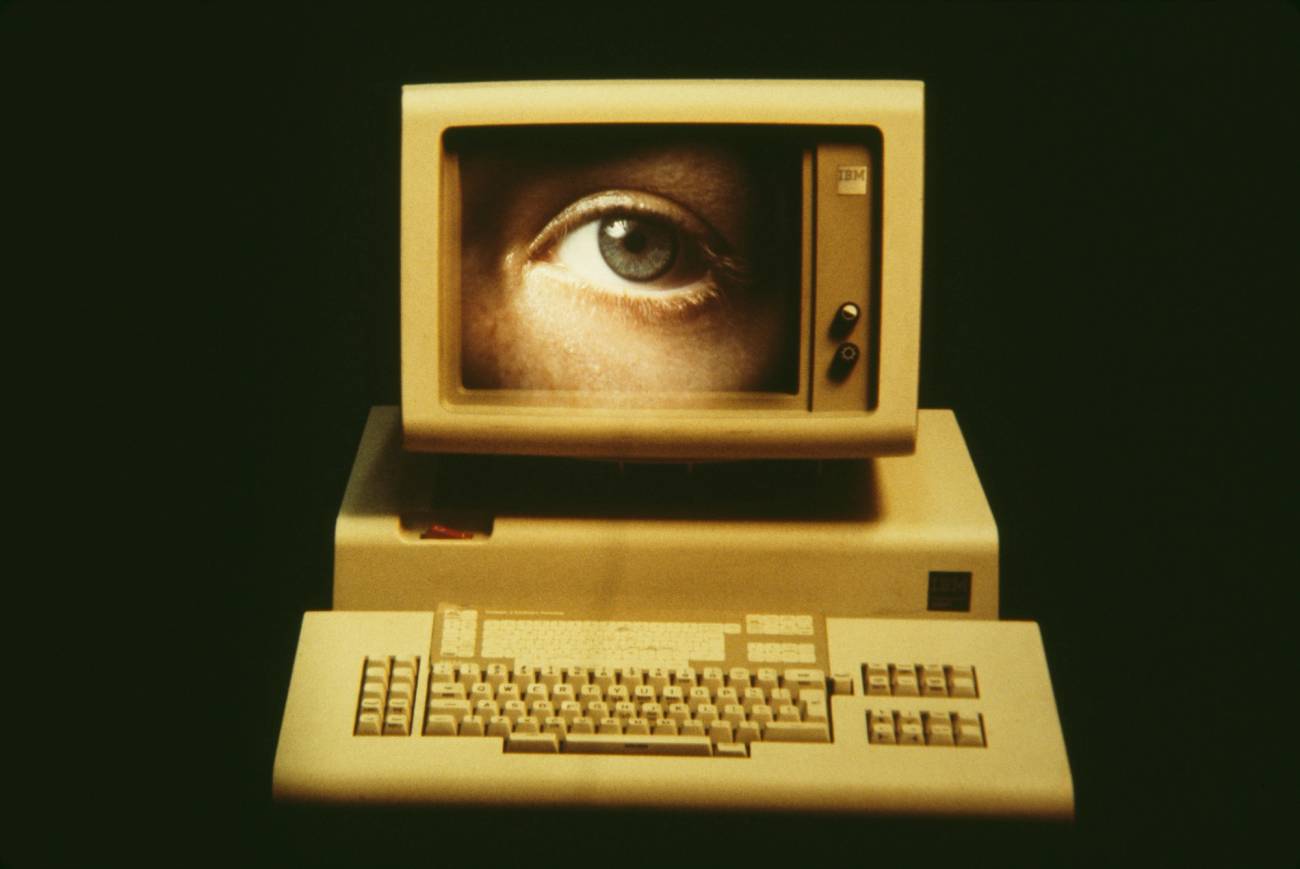

Alfred Gescheidt/Getty Images

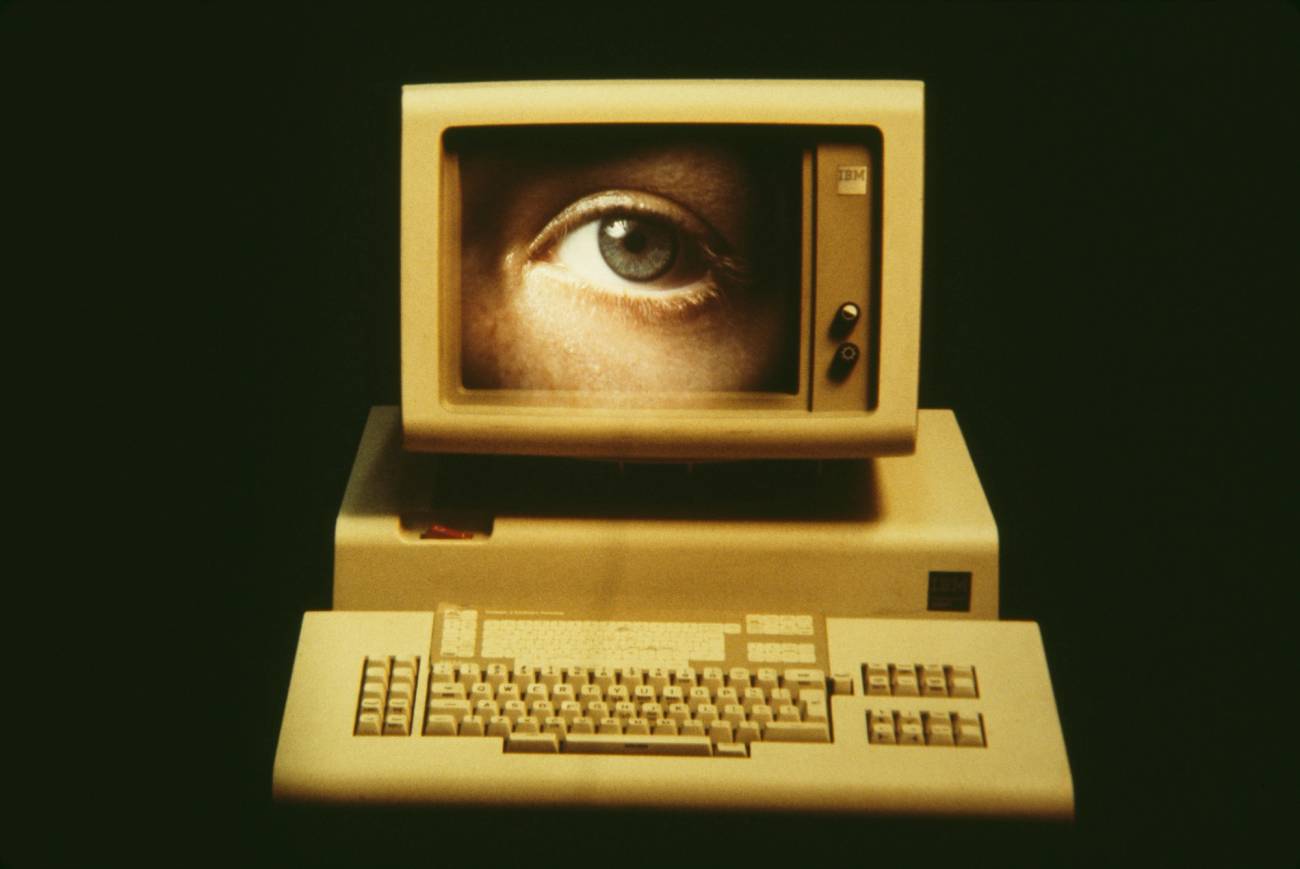

Alfred Gescheidt/Getty Images

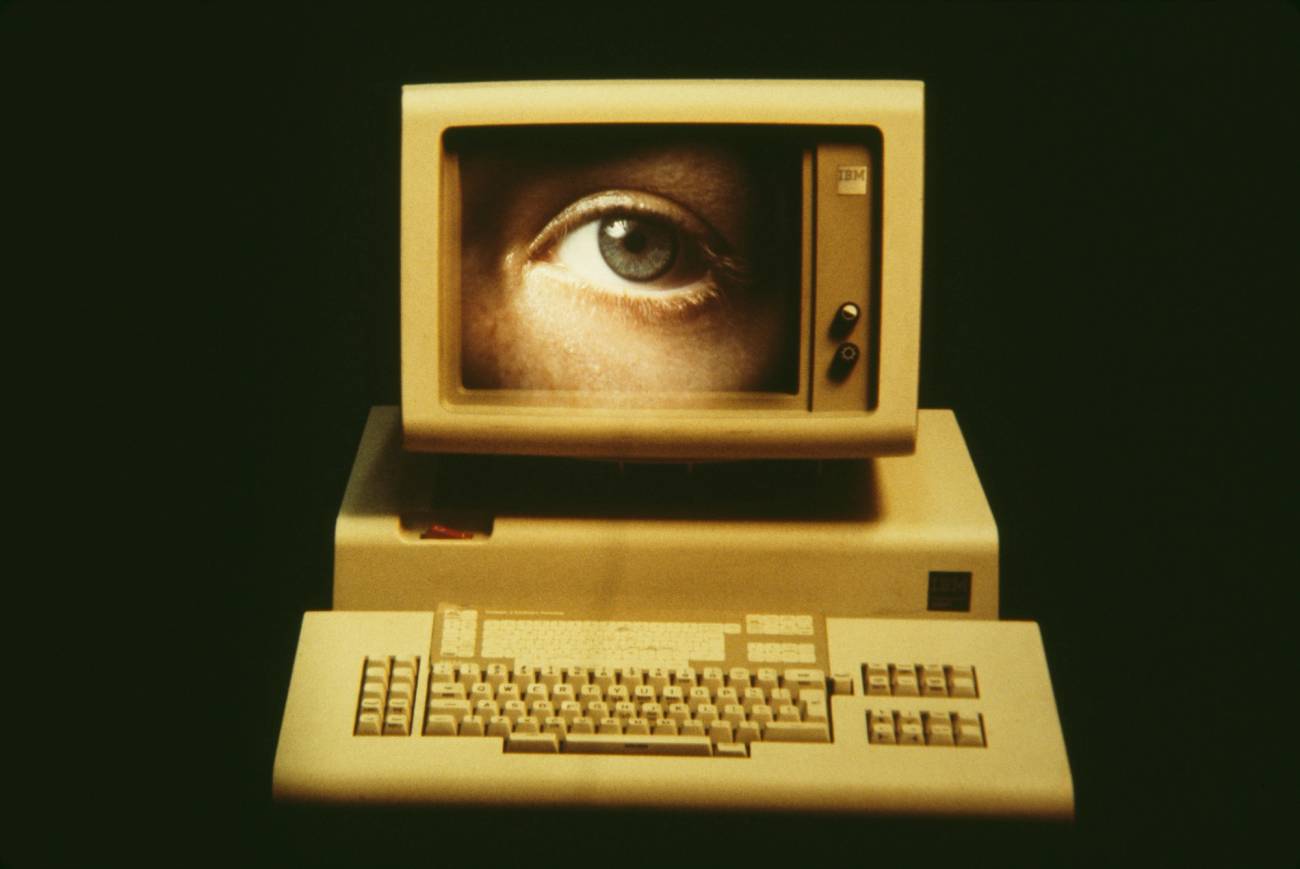

Alfred Gescheidt/Getty Images

My email was being “held in government quarantine” pending review, a letter from Yahoo! informed me. I was sitting in the computer lab in the German department at New York University. It was September of 2003. I remember because I’d just received an email about a merit scholarship for that semester. The government wants to know about my scholarship? was my first thought. My next one was: Let ‘em. What did I care if the government knew my GPA?

This is a common line of reasoning in the bulk surveillance era. The “nothing to hide” argument, which, as Edward Snowden points out, was likely the brainchild of Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels. Americans really took to it back in 2013, when Snowden revealed the government’s mass spying programs. Unless their private photos were being looked at, nobody cared.

Fast forward 10 years, and Americans seem to have adopted the same basic attitude toward the revelation that the government is spying on millions of social media accounts. So what if the government is spying on us—how else could it protect us from Russia and domestic extremists? Defenders of the new censorship regime focused on the politics of those censored, arguing over the finer points of what counts as a legitimate extremist threat. But they’ve missed the point: The government is reading our tweets, and monitoring our activity online, regardless of our individual political persuasions.

As a former military intelligence contractor told me: The real name of the game is data fusion. The government wants to collect tens of millions of tweets and cross-reference them with geolocations and credit scores, not so that it can protect Americans from Islamic terrorism or domestic extremism, but in order to exercise power. This is nothing new: In 1971, Sam Ervin, a Democratic senator from North Carolina, held a hearing on “Federal Data Banks, Computers, and the Bill of Rights,” the last of which, Ervin warned, was being trampled by the country’s security establishment. Ervin testified that “demonstrators and rioters” in the unrest of the 1960s had been treated not “as American citizens with possibly legitimate grievances, but as ‘dissident forces’ deployed against the established order.” And given that view, Ervin concluded, “it is not surprising that Army intelligence would collect information on the political and private lives of the dissenters.” Fast forward 60 years, and the FBI is still at it: BLM and J6 protesters, members of Congress and their campaign donors have all been investigated for links to terrorism. Of course, in the meantime, the Patriot Act provided an updated legal framework for this kind of overreach, giving intelligence agencies greater latitude than ever.

I’ve been asking around for years, and no one’s been able to tell me exactly what my letter from Yahoo! was about. A former intelligence officer I know offered the best conjecture yet. The surveillance programs that got going immediately after 9/11 were disorganized. New systems needed to be developed with clearer protocols, particularly when it came to surveilling Americans. Most likely, whatever agency was surveilling me was also surveilling my husband, a Lebanese immigrant. By law, the NSA doesn’t need to notify foreign nationals when it spies on them. My husband did not, incidentally, receive a letter like mine. But the NSA (in theory) can’t spy on me because I’m an American citizen, which means I fall under the FBI’s jurisdiction. In 1998, Congress passed the Security and Freedom Through Encryption (Safe) Act, which stipulated that citizens have a "right to be notified when their decryption information is provided to law enforcement, or when law enforcement is granted access to the plaintext of their data.” In other words, the FBI has to tell me when it looks at my emails.

The FBI and the NSA had a deal worked out: The FBI, which is technically a law enforcement and not an intelligence agency, became a front for laundering the vast quantities of data captured through the NSA’s bulk collection programs. The FBI’s Data Intercept Technology Unit (DITU) relayed NSA surveillance queries to companies like Google, Facebook, and Yahoo!, and then conveyed the results back to the NSA. So it’s safe to assume the FBI and the NSA were reading my email.

The government wants to collect tens of millions of tweets and cross-reference them with geolocations and credit scores, not so that it can protect Americans from Islamic terrorism or domestic extremism, but in order to exercise power.

In theory, the NSA was only after metadata, which is everything but the content of your communications. But you have to be credulous to believe that. According to NSA whistleblower Bill Binney, the government began trying to capture as much of the data of American citizens as it could mere weeks after 9/11. Binney blew the whistle because he’d seen the NSA abandon ThinThread, a program he’d developed that would have protected the privacy of American citizens. Instead, it went with Stellar Wind, which mined major communication databases for everything from phone conversations to emails to SMS’s. Theoretically, its scope was limited to metadata. By 2007, however, content was definitely on the menu. Prism, the program Snowden’s leak made famous, took content off the servers of major webmail providers like Google and Yahoo!—with their help, an arrangement that would be revived post-2016, when the government turned its sights on social media.

Stellar Wind and Prism represent one method of data collection: partnering with communication companies to capture metadata and/or content. Programs like Tempora took a different approach. Bypassing the need for corporate partnership, the NSA and GCHQ, the U.K.’s security agency, actually inserted intercepts into the fiber optic cables that make up the internet’s backbone.

“Unsubscribe from everything.” That was my lawyer’s advice to me. Anything with an even mildly political leaning needed to be banished from my inbox. Going forward, it would reflect the quiet, disengaged life I was to lead. Same went for my offline activity: no political protests. No antiwar anything. No The Nation, no Mother Jones. Cancel any subscription that might even hint at my political thoughts. And this was the kicker: Don’t vote.

If, back in 2003, government surveillance had reached a point that many of us felt the need to self-censor, today it’s private citizens who are imposing the censorship regime. Online mobs savage people for making an insensitive remark, communities shun people for asking questions. The desire to speak freely and without fear is driving not only the creation of platforms like Substack, but actual migration patterns. This is what happens when surveillance and social control are pervasive enough: True enemies, like al-Qaida, are replaced by boogeymen like @TrumpDyke, and dubious figments like "disinformation" supplant real threats like terror. The zealous among us begin policing speech so the actual police don’t have to, and the press, the inevitable organ of every authoritarian regime, either turns a blind eye or actively colludes with the government and its partners to smother unsanctioned views.

To the extent that there has been a debate about the abuses of power the Twitter Files revealed, it has revolved around whether dissenting voices—including those of distinguished scientists—should be censored for the greater good, but this is shortsighted. Censorship is a secondary effect of surveillance, and 9/11 elicited a sea change in the way intelligence agencies approach it. In Binney’s words: “we changed our policy of how we looked at communications and analyzed things from groups of people to individuals. That meant they switched from going after the bad guys to going after everybody.” Maybe today you’re on the right side of the surveillance machine, but that could change in an instant. Just ask Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, who went from being an obscure epidemiologist to a Twitter pariah overnight. Anyone can be put in the crosshairs.

The transition from the “war on terror” to the “war on disinformation” was seamless. The target may have changed—alleged Russian saboteurs became the new jihadists—but the essential tactics and players remained the same. As one of his last acts before leaving the White House, President Obama created the Global Engagement Center. It was originally called the Center for Strategic Counterterrorism Communications and was created to counter ISIS messaging online. However, beginning in 2017, the GEC’s new mission was to go after “counterfactual narratives abroad that threaten ... national security interests,” the idea being that Russian operatives had swung the election in Trump’s favor, a theory that has since been debunked. The GEC, it should be noted, was designed to facilitate coordination across multiple agencies—FBI, CIA, DHS, the Office of the President, and others—so its mission-shift resonated across the government at many levels, making Americans surveillance targets not just of any one agency, but of their government as a whole.

But the new mission was as much a private operation as a public one. The government- funded Aspen Institute‘s Commission on Information Disorder wrote the blueprint for how labor should be divided, and information, shared, in the great quest to snuff out “counterfactual narratives.” The commissioners suggested that social media platforms create an archive of high reach content, to be updated daily. At least under Prism, tech companies were merely asked to facilitate spying on Americans. Now they themselves do the dirty work, engineering the systems that allow bureaucrats to decide what Americans can and can’t say.

Back when he was still working for the NSA, Binney watched the Soviet KGB use surveillance to subvert the Russian public. The KGB’s tactic was to gain a window onto the Russian psyche and use that window to attack it, with the goal of enforcing obedience to the party.

The use of government surveillance to subvert Americans sounds pretty far out, but that’s only because we’ve grown so used to it. Doctors and scientists, who actually knew what they were talking about, were censored during the biggest public health crisis of our time. Meanwhile, Anthony Fauci, 21st-century America’s Trofim Lysenko, continued the lockdowns. What’s even more disturbing, untold numbers of doctors chose to censor themselves. They tended to be younger, early enough in their careers that they weren’t protected by established reputations and tenure. Dr. Bhattacharya, who is a professor of medicine at Stanford University, told me about colleagues who thanked him for speaking out when he began pushing back against the CDC’s policies on Twitter; they had wanted to speak out too but felt they had too much to lose. Bhattacharya is co-author of the Great Barrington Declaration, a document signed by close to a million scientists who felt lockdowns were reckless and unlikely to meaningfully impact death rates. For these views, Bhattacharya and other like-minded scientists were officially blacklisted, which meant that debate about the most far-reaching public health policies of our time was suppressed. We never talked about how effective, let alone disastrous, lockdowns might be because we weren’t allowed to, and the consequences of that were huge. The data is now in, and it turns out not only did lockdowns destroy the social fabric of American life, they didn’t actually work.

Mass surveillance and censorship are pretty much the norm now. We accept them, and downplay their impact. But COVID was a unique situation in that the cost of censorship could actually be measured: the irrecuperable learning loss kids suffered, the impact on early childhood development, the spike in deaths of despair, the damage done to mental health across the board but especially for teenagers, the historic economic downturn that decimated small businesses while leading to record profits for the tech industry.

We lost a lot for choosing not to have a dialogue about government overreach back in 2013, when Snowden revealed the government’s mass surveillance programs. “Study after study has shown that human behavior changes when we know we’re being watched,” he once said. “Under observation, we act less free, which means we are less free.” Maybe you hesitated to do a search on Google, or say something in an email because you thought someone might intercept it. After Snowden, writers admitted to turning down work out of the mere possibility of surveillance. The “war on terror” had a chilling effect on speech, which was bad enough. Fast forward to 2020, and scientists were voluntarily taking themselves out of the lockdown debate. If in 2013, we lost a core American value when we chose not to take up the cause of privacy, in 2020, we lost jobs and lives.

I began making FOIA requests not long after the Snowden leak. It seemed like a reasonable thing to do. There was more concern about government transparency by then, and I had a lot of questions. Like why had my husband and I been surveilled? He was a pot-smoking, jazz-playing Christian, and I was a Jewish grad student. I figured I was entitled to know why our privacy had been violated in the name of national security. So when a letter with a CIA return address arrived in the mail, I tore it open, eager. Inside was the first of many Glomar responses I’ve received.

We can neither confirm nor deny the existence or nonexistence of records responsive to your request. The fact of the existence or nonexistence of such records is currently and properly classified and relates to intelligence sources and methods of information that are protected from disclosure …

Some legal mind at the CIA came up with the copy back in 1975. The agency had wasted a fortune on Howard Hughes’ Glomar Explorer, which was meant to retrieve a sunken Soviet sub from the bottom of the ocean. It failed in its mission, at great taxpayer expense. A journalist at the Los Angeles Times wanted to report on it, and the Glomar letter, the government’s last line of defense against transparency inquiries, was born.

Secrecy protects surveillance systems. It’s how, as the tools of authoritarian regimes, surveillance systems work: The eye only faces one way, and you don’t get to look back. But withholding information is also a way of undermining the person who seeks it. Because we need context, we need stories, we need truth, especially after a traumatic event.

What story will America tell about the past two decades? What will our grandkids learn about the Patriot Act? About Snowden and the Twitter Files? What will their textbooks say about COVID?

Will they mention the suicides, the exodus of kids who have seemingly given up on school, or the fact that the teachers union backed shutdowns—that it was the schools that first gave up on America’s kids? Will we tell the story of how avoidable it all was? Or remember that there was a surveillance state long before the apparatchiks began telling doctors what they could and couldn’t say?

But if the truth does come out, it will show that we knew. We knew the government was spying on us. We were warned again and again, and we did nothing.

Justine el-Khazen is a writer living in Brooklyn, New York.