Agudath Israel and the Diocese of Brooklyn were the victors in a dramatic, 11th-hour, Nov. 25 Supreme Court decision that prohibited New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s Executive Order 202.68 from restricting attendance at the state’s houses of worship, as part of an effort to combat the spread of COVID-19. This victory seems likely to resonate across the country in the ongoing national debate over whether or not religion is essential during times of emergency. After the SCOTUS decision, Agudath Israel and the Brooklyn Diocese had to argue the merits of their cases before a panel of judges at the 2nd Circuit, which had denied the two groups’ appeals for preliminary injunctions after the Eastern District of New York denied their initial filings for injunctive relief.

Cuomo’s executive order limited houses of worship in “red zones”—those areas the state determines have the highest infection rates—to attendance of just 10 people, and in precautionary “orange zones” to 25 people. The order also put percentage caps on religious attendance, restricting houses of worship to 25% capacity in red zones and 33% in orange ones—if those limitations bring the total attendance to less than 10 or 25 people, respectively. Meanwhile, the state allows retail businesses to operate at 50% capacity.

On Dec. 28, the merits panel agreed with the Supreme Court, determining that the individual caps on religious attendance threatened free exercise of religion under the First Amendment. In providing the background of their decision, the panel noted that the order’s strict guidelines occurred within the context of comments by Gov. Cuomo blaming COVID-19 clusters on Orthodox Jewish communities, and placed these guidelines alongside the order’s laxer restrictions for essential businesses, a category so broad as to include “news media,” apparently in its entirety, as well as shuffleboard and farmers markets.

Just as New York policymakers justified discrimination against Orthodox Jewish communities in the name of public health, some public health experts and advisers are considering privileging identity in determining the rollout of COVID-19 vaccinations. In a December 2020 piece in Tablet, Liel Liebovitz questions why the Orthodox Jewish neighborhoods that Cuomo and New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio have identified in public remarks as hotbeds of disease have not been similarly singled out by New York City’s Taskforce on Racial Inclusion and Equity to be prioritized for vaccination. Such an oversight would seem to contradict the rationale for restrictions on Orthodox Jewish communities put forward by Cuomo and de Blasio: namely, that Orthodox Jews are uniquely responsible for dangerous coronavirus clusters that threaten the health of their fellow New Yorkers.

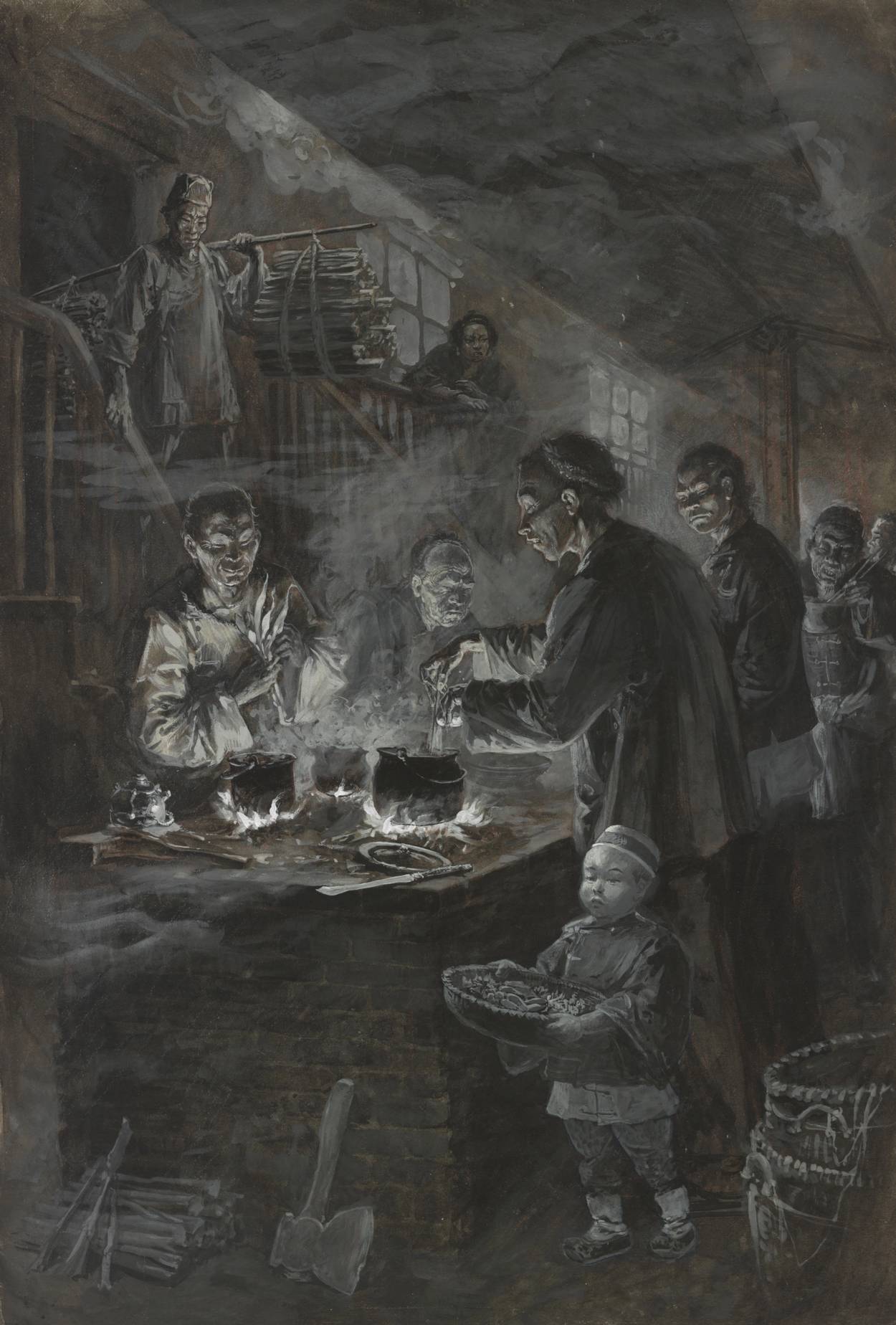

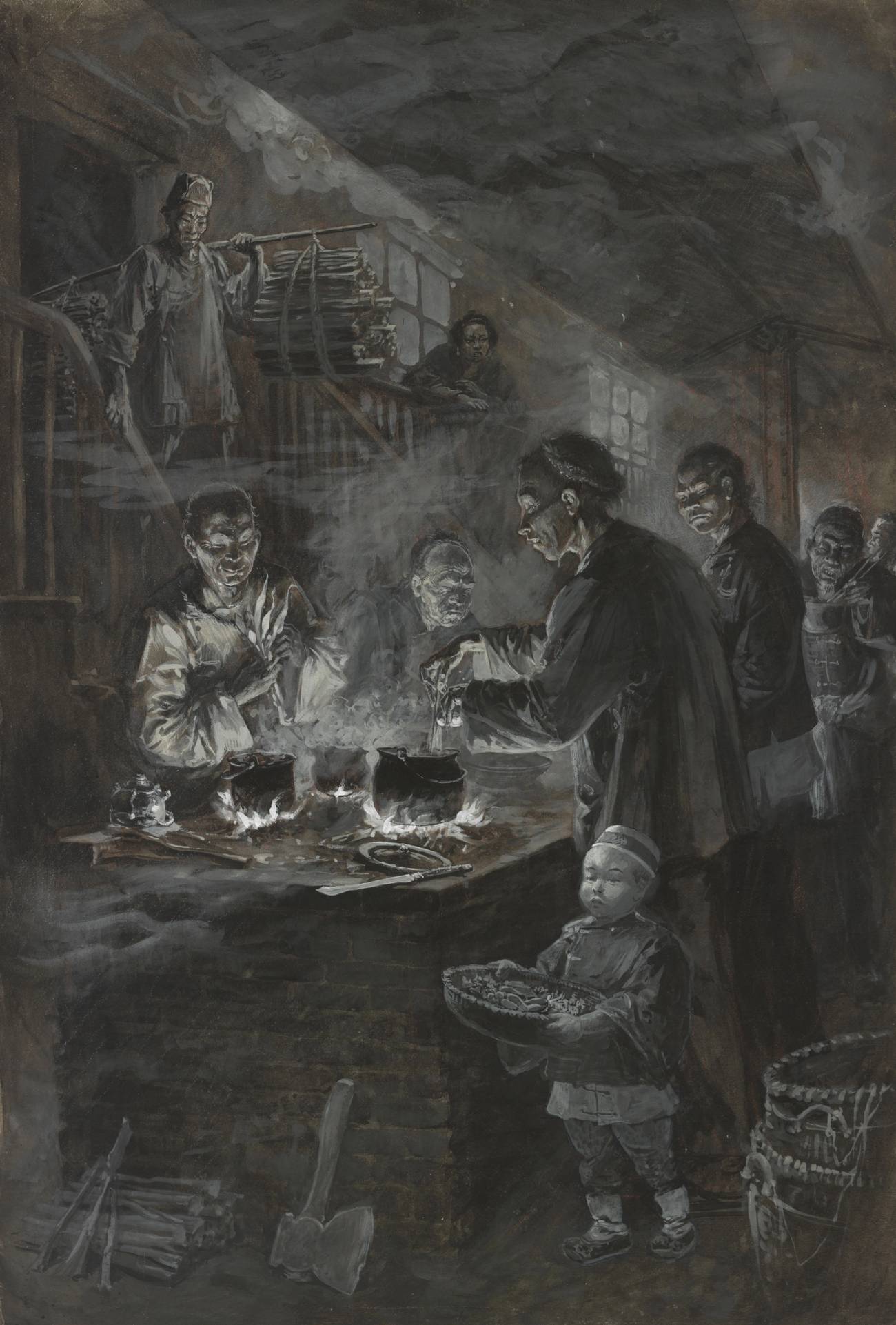

De Blasio’s and Cuomo’s remarks have historical parallels in the events surrounding Wong Wai vs. Williamson, a forgotten instance of early-20th-century public health case law which also finds its origins in political and civic leaders’ concerns over contagion. When a small bubonic plague outbreak hit San Francisco early in the year 1900, UC Berkeley law professor Charles McClain observed in a 1988 American Bar Foundation article, “The Chinese quarter of San Francisco had for years been depicted by local health authorities, often in the most garish terms, as the city’s preeminent breeding spot for disease and contagion.”

To combat a federal and local response to the outbreak—which included sudden, state-enforced quarantine of the city’s Chinatown area, restricted movement in the state and around the country for both Chinese and Japanese persons, and coerced vaccinations using a harmful and largely ineffective experimental vaccine—a Chinese merchant in San Francisco named Wong Wai filed a bill of complaint in the U.S. Circuit Court for the Northern District of California.

Ultimately, the district court judge, Judge William Morrow, enjoined the public health authorities at both the local and national levels from their vaccination scheme. Public health officials could not of their own accord act above the law in order to protect the public in time of a health emergency. Morrow asserted this violation of the 14th Amendment was “boldly directed against the Asiatic or Mongolian race as a class, without regard to the previous condition, habits, exposure to disease, or residence of the individual.”

One has only to update Morrow’s language for it to apply to the effects of Cuomo’s Executive Order 202.68 on Orthodox Jews “as a class, without regard to the previous condition, habits, exposure to disease, or residence.” Just prior to the issuance of his executive order, the governor asserted that New York’s initial COVID-19 hotspot was caused by an Orthodox Jewish man at temple, saying: “Orthodox Jewish gatherings often are very, very large and we’ve seen what one person can do in a group.” After this preface, he informed the press he was meeting with representatives from “the ultra-Orthodox community” and would “close the institutions down” if they would not observe COVID-19 mitigation rules. Four days after this statement, Cuomo appeared on CNN, saying his order was in response to “a predominantly ultra-Orthodox cluster.”

In the realm of religious observance, the safety-first worldview is turning politicians into amateur theologians.

The 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals decision cites an Oct. 14 statement by Cuomo that specifically calls out the religious practices of Orthodox Jews, blaming them for the spread of COVID-19. It is hard to see how these remarks would be admissible in American society if they referred to other minority groups. For his part, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio has made a host of problematic statements that would seem to frame his administration’s decision to prioritize other groups ahead of Orthodox Jewish neighborhoods as a discriminatory and/or punitive act.

As states across the country grapple with whether and how to prioritize COVID-19 vaccine distribution by racial groups, overt discrimination against communities in which ethnicity and religion are deeply entwined may become normalized as the other side of the identity politics coin, any group that earnestly practices a religious faith may come to be viewed as dangerous or alien. Simply by virtue of being conspicuous in dress and appearance, customs and mores, ethnoreligious groups in particular may continue to see themselves and their practices viewed with increasing suspicion and hostility and find themselves targeted by public officials in ways that violate settled law.

Increasing public religious disaffiliation is likely to become a key factor in religious liberty suits of the future. As the Agudath and Brooklyn Diocesan suits arguing for the essentiality of religion attest, some decision-makers seem to perceive the prioritization of moral goods to be part of their public duty. Politicians and public health experts, for example, will give their imprimatur to a bit of risk if the cause is viewed as sufficiently just, as in the case of the George Floyd protests over the summer, or even to marijuana dispensaries—while “cracking down” on communities whose beliefs are seen as retrograde, unfashionable or unpopular by their constituents, despite being constitutionally protected.

As the pandemic continues on, leaders at various levels have been elevating antiseptic doctrines of public safety to the level of social goods—despite those doctrines being absent from the law. In the realm of religious observance, the safety-first worldview is turning politicians into amateur theologians. Jews seeking to form a minyan or a Catholic who requires the Sacraments may differ with Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam, who opined in a pre-Christmas press conference, “You don’t have to sit in the church pew for God to hear your prayers ... Worship with a mask is still worship, worship outside or online is still worship.” For some, sure. For others, maybe not.

Although both Agudath Israel and the Diocese of Brooklyn made clear in their briefs that their respective synagogues and churches were at great pains to be responsible and to protect their congregations from the spread of COVID-19, a prevailing attitude persists in some quarters that in-person prayer and worship—even with the recommended health and safety protocols in place—is gravely irresponsible, because it is presumably a dispensable, discretionary act of relatively little social value. Because New York state did not consider religion essential when crafting Executive Order 202.68, it seems to have considered religious activity’s low exposure rates immaterial—until the courts got involved. This, despite Cuomo’s own recent acknowledgement that religious activities were responsible for only 0.69% of COVID-19 exposure in the state between the months of September and November—a rate less than or similar to other sectors the state categorizes as “essential.”

Policy impacts need not be intentionally anti-religious to be discriminatory, but religiously illiterate policymakers seeking to redress wrongs done to historically marginalized groups may inadvertently harm other communities by sheer virtue of the fact that they are allocating finite resources within limited time frames.

Moreover, in a country lacking a shared moral vocabulary, the courts will continue to be viewed as the only effective way to resolve contentious disagreements. Filings against the practices of ethnoreligious minorities and religious groups may become a preferred stealth tactic of entities attempting to curb religious practices they perceive as a threat to the common, i.e., secular, good. As long as this status quo remains, the 2nd Circuit panel’s recent decision and Wong Wai vs. Williamson—with their considerations of otherness, the public good, and the state’s responsibility to remain neutral with regard to both—stand as bulwarks against discrimination.

Agudath Israel attorney Avi Schick, who argued the group’s case against Executive Order 202.68, believes the 2nd Circuit’s decision will have a long-lasting impact, one that “goes far beyond COVID.” According to Schick, “It is an unequivocal statement from the Second Circuit that government can’t restrict religious conduct when it ascribes no value to religious practice. What the United States Constitution has to say about the essentiality of religious activities trumps what the Governor says about it. This decision will serve as a brake on governments contemplating restricting religion, and as a basis for courts to set aside those restrictions when government does not heed its message.”