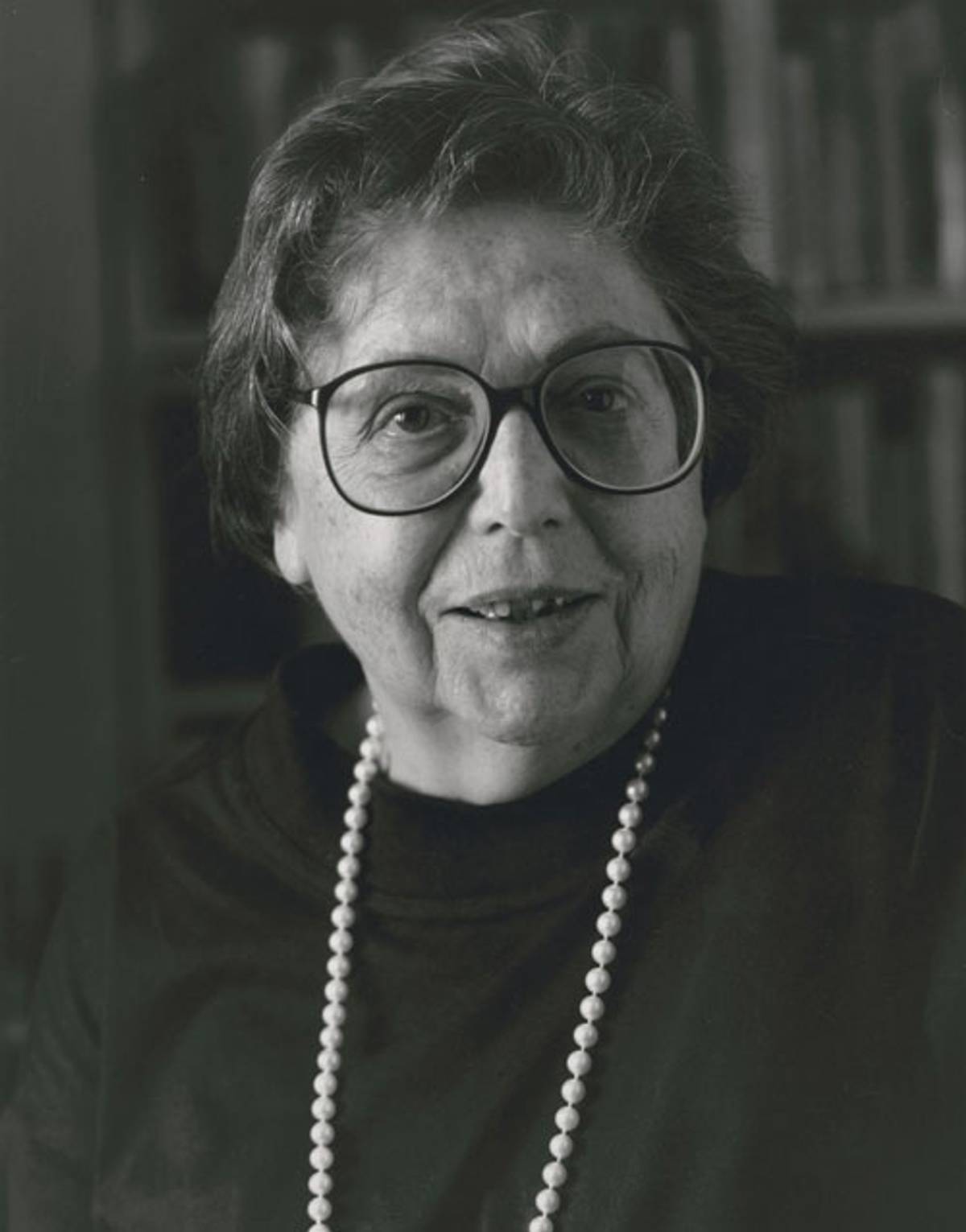

Lucy Dawidowicz, the Yiddish Eagle of the Bronx

The strong-willed scholar of Jewish life and history died 29 years ago today

I met the Holocaust historian Lucy Dawidowicz in 1982. I was dean of the College of Liberal Arts at the University of Texas at the time, and I had invited her to give the prestigious annual Gale Lecture in Jewish Studies that was in my remit. I had met her briefly earlier in New York at the old YIVO (Institute for Jewish Research) at 1048 Fifth Ave., now the Neue Galerie, where she had given a moving appreciation of the great Yiddish linguist Max Weinreich on the publication of his life’s work Geshikhte fun der yidisher shprakh (History of the Yiddish Language).

I liked her brisk no-nonsense affect immediately but circumstances didn’t permit more than a few words between us. I resolved then and there to have her to Texas.

A word of full disclosure, or something along that line, might be in order here. Though I am a Christian, not a Jew, I have taught Yiddish at various levels, and published a number of essays on the history of the Yiddish language. I grew up in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, which may not seem like a hotbed of Yiddish culture, but like many Southern towns of the time in fact had a sizable Jewish community; most of my high school friends were Jewish, often with Yiddish-speaking grandparents from points east and north. The first time I ever tasted a matzo was on a fishing trip in southern Mississippi with my buddies. I taught myself Yiddish in the 1960s out of Uriel Weinreich’s College Yiddish, and my wife and I are surely the only gentile couple in the world who spoke in Yiddish when we didn’t want the kids to understand what we were saying.

Lucy (she shoved aside my “Professor Dawidowicz” the first time I used it) gave us a marvelous lecture on the controversial role—actually, in her view, the lack of a role—that the American left had played during the Holocaust; the gray establishment (and conservative) Jews had done a lot more to save Jewish lives, as she saw it.

That was what got Lucy Dawidowicz in the trouble she enjoyed so much: tossing Molotov history-cocktails expertly into previously quiet, still corners of liberal Jewish guilt and ambiguity. She had taken the first step in that direction in the 1950s defending the verdict and death sentences of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, a position so radical in her circles that I had to wonder if she had any friends left after publishing “The Rosenberg Case: ‘Hate-America’ Weapon,” in socialist The New Leader (1951) and “‘Anti-Semitism’ and the Rosenberg Case: The Latest Communist Propaganda Trap,” in Commentary, vol. 14, July 1952. For what little it’s worth, I still think Ethel Rosenberg should not have gotten the electric chair; her guilt was less than her husband’s, and the couple had young children. But I found something compelling about Lucy’s willingness to take such an uncompromising and unpopular position.

Lucy and I hit it off instantly. We hadn’t been talking 10 minutes when she told me the joke she claimed she had just heard in the checkout line at Zabar’s, and which she told me in Yiddish. The joke goes like this: An African American man was sitting in a subway in New York, wearing a black hat, thick glasses, clothed in black, head to toe, with peyes (earlocks), reading the Yiddish-language Forverts. A Jewish Hasid gets on the subway, and he can’t believe what he’s seeing. After squirming about a bit, finally his curiosity gets the better of him and he leans into the aisle and asks his neighbor: Ir zayt a yid? (“Are you a Jew?”) The other man looks up from his Forward and says, dolefully: Dos felt mir nokh (“That I need like a hole in the head”). I cracked up when Lucy told it. And with that, we became friends.

My work took me to New York a lot in the 1980s, and when time allowed I alternated getting together with her and her neighbor across West 86th St. at Broadway, Isaac Bashevis Singer. She said she had seen the Nobel Laureate frequently on the street but had never summoned the nerve to speak to him. Although I was friends with them both, nine horses could not have got me to try to arrange a get-together. As the saying goes, I may be dumb but I’m not stupid.

My routine with Lucy went like this. I’d take a taxi to her place bearing a dozen roses and a bottle of the most expensive Scotch whisky I could afford. A few drinks at her (rent-controlled) apartment, then up Broadway to a Chinese restaurant she favored. Though she kept her apartment glatt kosher, with two sets of dishes and cooking pans, the oven blowtorched by a rabbi, the whole thing, the kashrut rules didn’t apply when she was off the rez. She always ordered the sweet and sour shrimp, though she never ordered the sweet and sour pork.

And we’d talk. I was very much involved in Yiddish linguistics and internecine warfare within that narrow, pinched domain and she had known personally almost all of the heavy hitters: Max Weinreich, Uriel Weinreich (Max’s son, the brilliant and charismatic Columbia University linguist who wrote College Yiddish), Zelig Kalmanovich, and Zalman Reisen among others.

I told her once about the article I was thinking of writing on a narrow linguistic issue in Yiddish spelling—the use of “silent alef” (shtumer alef) for words beginning with the vowels i, u. Standard YIVO orthographic rules contemn shtumer alef, but it is still used in some publications and a lot in private correspondence. Two of the great Yiddish linguists (call them X and Y) had fought over this issue most heatedly in article after polemical article throughout the 1950s into the ’60s, inventing new demolition arguments with every renewal of battle.

Lucy was never much interested in nitpicky linguistic matters like that, as I could tell over my Hunan beef and her sweet and sour shrimp. She was giving me what I privately had taken to calling her “Lucy-the-raptor look”: suspicious, disapproving, talons barely sheathed, ready to swoop and pounce.

Finally, she had heard enough. She held up her hand and said, “Stop. I hear all this linguistic stuff you’re talking about. I get what you’re saying, but let me tell you, Bob, it’s garbage what you’re talking. You’ve got hold of the wrong end of the stick. Their argument had nothing to do with linguistics. It was because X was short, rumpled, and not all that good looking, while Y was tall, always dressed comme il faut, and handsome. All the girls would like to have slept with him. Their argument wasn’t linguistic; it was nothing but jealousy.”

Well, that was that. Her straight talk put paid to my plans to write on this recondite little Akademikerstreit (“professor piffle”) in Yiddish linguistics. After I finished laughing, I told her thanks, but I wouldn’t be touching that topic with a 10-foot pole, no way. I was grateful for the dose of hard truth.

Lucy was like that: no-nonsense, direct, ordinarily funny about it. I suspect she got along better with men than women. Several women who worked for her or with her have told me that they were mostly just afraid of her. I was never afraid, though she didn’t hesitate to put me in my place whenever she thought I was wrong about something.

We talked mostly about Jewish and Yiddish matters. I was helping her raise money for her project to translate Yiddish and Hebrew masterpieces into English. For that other enthusiasm of my life, India, she had no use whatsoever and never passed up a chance to needle me about it. Gandhi had counseled European Jews in World War II to passive acceptance of their martyrdom under the Nazis. Thus the Mahatma: “I do not consider Hitler to be as bad as he is depicted. He is showing an ability that is amazing and seems to be gaining his victories without much bloodshed”; and “The Jews should have offered themselves to the butcher’s knife. They should have thrown themselves into the sea from cliffs.” So it didn’t entirely surprise me that Lucy never had anything good to say about Gandhi, India, or Indians.

***

Lucy Dawidowicz nee Schildkret was born to blue-collar immigrant Jews from Poland. She spoke in the accents of the Bronx to the day of her death. (“Dawidowicz,” incidentally, is pronounced dah-vee-DOH-vich.) Rather on the pink-diaper side, she was a member of the YCL (Young Communist League) in her teens. She had originally wanted to study literature but had changed course in the 1930s as the implications for Jews of Hitler’s rise to power in Germany became clearer to the outside world.

In 1938-1939 she spent a year in Vilna (Vilnius), Lithuania, then the original home of YIVO, on an aspirantur—a graduate fellowship. There she got to know Max Weinreich, the director of YIVO, and even lived with his family for a while. She got out safely to America only a few weeks before the war broke out and the Einsatzkommandos started moving into Lithuania and killing every Jew they could get their hands on. She described that year, the last year before the destruction of the Yerushalayim d’Lite, the Jerusalem of Lithuania, in what is her warmest, most personal, and most intimate book, From that Time and Place (1989), which is so marvelously evocative of the tone of life and the precarious position of Jews and the Yiddish language in that most Yiddish of cities.

After the war, she married a survivor, Szymon Dawidowicz, a Bundist leader, and they enjoyed by all accounts a happy marriage from 1948 until his death in 1979, which is described to some degree in the admirable biography by Nancy Sinkoff, From Left to Right: Lucy S. Dawidowicz, the New York Intellectuals, and the Politics of Jewish History. She also resolved never to set foot in Germany or Austria again, and she didn’t.

Her first book was The Golden Tradition: Jewish Life and Thought in Eastern Europe (1967). The book however that brought her to widest recognition and controversy was The War Against the Jews, 1933-1945 (1975). In it she argued that Hitler’s driving force was the destruction of world Jewry. He wanted more Lebensraum, sure. He hated communism, right. But, front, center, back, left, and right, Lucy argued, it was his hatred of Jews that infused him right up to his death by suicide as the Russians were closing in on Berlin. His last will and testament, written in the bunker a day before his death, speaks of “international Jewry and its helpers.” This, said Lucy Dawidowicz, was Hitler’s obsessional Lebensmotiv: Death to the Jews!

Other historians, who are professionally allergic to categorical answers, took issue with her thesis, and accused her of ignoring and misinterpreting historical data and otherwise being wrong. But Lucy stood her ground and never conceded an inch. She knew what she knew. Her other books attracted less controversy but she always had her critics, mostly from the left. Everything she wrote holds up remarkably well, however: A Holocaust Reader (1976); The Holocaust and the Historians (1981)—a harsh criticism of other historians’ evasions and hypocrisy in dealing with the Holocaust; the collection of essays, mostly from Commentary, titled On Equal Terms: Jews in America, 1881-1981 (1982).

One of her essays in Commentary I liked very much for its honesty, and its revelation of the warmth of her attachment to traditional Judaism, was titled “On Being a Woman in Shul.” It appeared in the July 1968 issue of Commentary, at the very beginnings of the modern feminist movement, but Lucy would never be much of a feminist. The synagogue she attended was a middle-class Orthodox shul in Queens, and she felt comfortable there. “To my astonishment—for I thought myself modern—I find I like the partition” between the sexes. And then this: “One reason why women gossip in shul is, of course, that they have an innate feminine proclivity for it.” And she quotes in support Elijah ben Solomon, the Gaon (prince) of Vilna: “Of ten measures of talk that came down to the world, women took nine.”

“Woke” Lucy Dawidowicz was not. But there is a richness in the historical detail of her work that rises above the liberal/conservative, woke/retro binarity. I do not claim to understand the Holocaust very well—why one supposedly civilized, gifted people tried to exterminate another civilized, even more gifted people—but without Lucy Dawidowicz’s books I would understand it not at all. Texture is what she brings to the table; one feels that one was there, grasping at rotten potato peels in the ghetto or in Ponar forest awaiting a bullet in the back of the neck. An invaluable guide to her work, and to her as a person, was published posthumously by her friend Neal Kozodoy, What Is the Use of Jewish History? Essays by Lucy S. Dawidowicz.

In 1987, when the Iron Curtain had begun to tear and was eventually to disintegrate, I was invited to the University of Kraków, Poland, to participate in a celebration of the Solidarity movement that presaged the demise of communism in the Iron Curtain countries. The Jagiellonian University is the oldest university in Poland, the second oldest university in Central Europe, and one of the oldest surviving universities in the world. I decided to make a family thing out of it and took my family on a driving trip from West Germany into Czechoslovakia, Poland, East Germany, then back out to West Germany. We rented a car in Belgium, me, my wife Karen, our two boys, Kevin and Michael (aged then 11 and 8), and my mother-in-law Helen Russell.

This was an exposure to communism at its most wretched. Everything in all three countries was gray, gray, gray—and scary. A restaurant menu would list about a hundred choices, but all you could really get was potatoes and a pork chop or beefsteak tartare and, on a good day, stale bread slightly moldy. (The ice cream was OK, but they always served it with fruit cocktail from a can which my boys loathed. Oy vey iz tsu vaynen.) With a foreign rental car you got traffic tickets, payable in cash to the smirking cop on the spot, for trifling offenses. Gasoline was rationed and you had to line up at a post office to get ration cards before you could purchase even a few gallons. The border guards were straight out of John le Carré’s The Spy Who Came in from the Cold: heavily armed, bovine, and thuggish (bolvanes or bulvanim in Yiddish), unsmiling as wolves, wordless. Crossing the border into one of those communist countries, in a rented car, was harrowing enough to inoculate my sons against communism for life.

One of the high points of the trip was visiting the Jewish cemetery in Warsaw, miraculously preserved as by God’s hand from total destruction during the Nazi occupation. There one could pay respect in the shraybers ek, the little corner of the cemetery where many Yiddish writers are buried. We had gotten there at about noon on a Friday, which was late enough in a communist country for the cemetery watchman, a man in his 50s, to start thinking about quitting work for the day. He didn’t want to admit us. I spoke to him in Yiddish, and that changed everything. He gave us an unforgettable tour of the cemetery, pointing out a drain where, as a boy, he had been one of the shmuglers who were small enough to go through the sewers from inside the Jewish ghetto to the outside and smuggle food back into the ghetto.

It was a very moving experience for all of us, the high point of the trip, and I looked forward to telling Lucy about our experience. As I did so, on our return, I began to sense the ever-feared “Lucy-the-raptor” face of which I wrote earlier. Something about what I was telling her wasn’t going down well. “This guy, he was a Jew, you said?” she asked. “Yes, right, he was Jewish. We spoke Yiddish.” Chary now, I went on and told her the whole story.

When it was over, she asked “Well, if he was Jewish, why hadn’t he left Poland?” As it happens I had asked him the same question.

“Family,” he said, “And communism: I believe in communism.” I told that to Lucy. She didn’t say anything for what seemed like a very long minute, and then finally this: “Well, Bob, lemme tell you something. I’ve thought about this a lot my whole life, I’ve read about it and thought about it and written about it again and again, and here is what I’ve concluded: F—K ALL COMMUNISTS!” Delivered in the purest accents of the Bronx. Lucy at her best, tough, all 5-foot-nothing of her (as she described herself).

The last time we spoke was some months before her death. She had called me up to ask about a Holocaust denier who was claiming to have a connection to the University of Texas. Mercifully he didn’t, and Lucy and I talked about getting together on my next trip to Manhattan. She mentioned a well-known Jewish intellectual she might like to include in our drinks and a meal but, thinking it over for about a second, went on, “Nah, he talks too much.”

A final visit didn’t work out. I miss her very much, still, after almost 30 years. I loved her, and every minute I got to spend with her. I go on a Lucy binge about every five years and reread all of her books. Each year I privately honor her yortsayt—she died Dec. 5, 1990—by offering up a silent prayer to her spirit and to God for the privilege to have had her as a friend, always talking to me in the unfiltered accents of the Bronx, and ready to swoop.

Robert King taught linguistics, Jewish Studies, and South Asian Studies at the University of Texas from 1965 until his retirement in 2016.