The Nazis Are Coming

How the day neo-Nazis marched in America—and Anne Frank—made my Israel

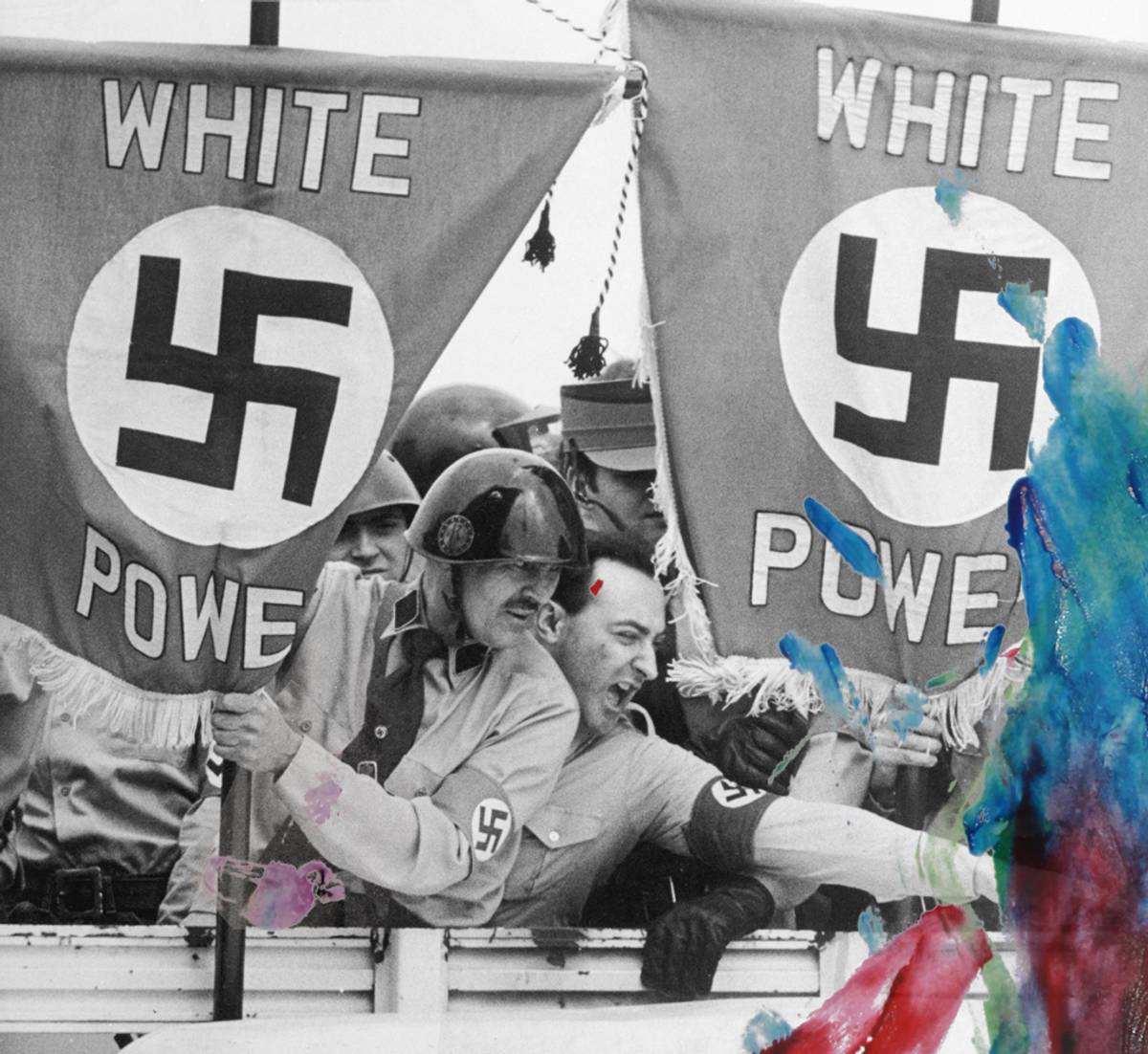

When the 11 Nazis unfolded their banner that screamed, “Holocaust—Six Million Lies,” they were hit with eggs and rocks by the 2,500 counterdemonstrators who came to protest. A police helicopter hummed and lingered over the crowd. After seven minutes, the Nazis retreated, hiding under their swastika-painted shields. It was Sunday, Oct. 19, 1980, and the Nazis had obtained a permit to march—exercising their right to free speech—at Lovelace Park in Evanston, Illinois, the suburb just north of Chicago and home to Northwestern University. The counterdemonstration was sponsored by the B’nai B’rith Hillel Foundation of Northwestern and other Jewish and local interfaith groups in Evanston. The Nazis had originally applied for the permit to hold their rally a month earlier on Yom Kippur, which fell on Saturday, Sept. 20, that year. The mayor at the time, James Lytle, turned them down for that particular day, but granted them the permit for 39 years ago this weekend.

I was 10 years old in 1980, and I remember the day of the march. It was four miles from my home. I had just returned from Sunday school at our synagogue in Skokie, the suburb just west of Evanston. Oddly, no one mentioned the march, or perhaps, I just don’t remember anyone talking about it. That day, my Sunday school teacher, an old Israeli woman with long droopy eyelids smothered with thick bright green eye shadow, had us paint the State of Israel with our fingers on heavy construction paper. After sketching the outline of the tiny country, we dipped our fingers into plastic bowls of green, yellow, blue, and red paint and made a mess on our paper as we tried, and failed, to color within the lines of the country’s borders.

With our moist, dirty fingers, we created grass and mountains and water and flowers in an abstract place that felt far away from us. When we finished, we lined up the papers by the window sill and compared. A cold official map of Israel 20 times larger than our individual letter-size sheets loomed over us from across the room. Pitted against the authentic state, every student’s Israel looked misshapen, distorted, colored out of the lines, dripping like it was melting.

When I came home from Sunday school, I prepared for the Nazi march. I ate Cheetos at the kitchen table and then walked downstairs and hid in the basement of our house in a corner under the pingpong table. Though I had heard that the Nazis were marching, I’m not sure where I knew this fact from, since my memories of it seem to consist of me feeling alone. I was scared. I bit my nails until they bled, thinking of Nazis in brown uniforms with shiny black belts and my melting state of Israel, too, from earlier in the day, as I heard my family walking in the kitchen. After a few minutes I got bored and my fingers were sore, but I wasn’t moving. The Nazis were coming. A bit of green paint had remained on my hand. It mixed with some orange Cheetos crumbs. On my palm, I drew an imagined distance from Jerusalem to Tel Aviv with my finger. After hiding for about an hour, my father came downstairs and saw me in a fetal position under the pingpong table.

“What are you doing?” he asked.

“I’m hiding from the Nazis,” I answered.

“Get upstairs,” he quipped, “and finish your chores.”

I had learned about the Holocaust for the first time a few years earlier at Hebrew school at the same synagogue from the same old Israeli woman with the glinting green eye shadow. I remember one day in particular, when she wanted us to feel what it was like to be Anne Frank hiding in the attic. That day, she made our class sit quietly for 20 minutes. She used a kitchen timer and told us we needed “to know what it felt like to have to be still all day like the Franks up in the attic.” It didn’t work. After a few minutes, one student said he had to pee and another farted and then everyone giggled. We were mostly upper-middle-class 7-year-old Jews learning what it was like to be oppressed but we had treated the Anne Frank activity like a game and we just didn’t get it.

Now, though, I wonder if learning about Anne Frank experientially that day made more of an impression on me than I thought. Like others, I’ve been obsessed with her story for as long as I can remember. I’ve read all the different versions of her diary several times (I return to Melissa Mueller’s biography every few years). I’ve written bad poetry about Anne, for Anne, seen every play and film that I could. I’ve scoffed at the ways Anne’s diary has been sanitized, too, captured by Cynthia Ozick in her 1997 essay, “Who Owns Anne Frank?” “The diary has been bowdlerized, distorted, transmuted, traduced, reduced,” Ozick writes, “it has been infantilized, Americanized, homogenized, sentimentalized; falsified, kitschified.”

My obsession with Anne Frank came from her darker moments, not the ones that have been universalized by readers into hopefulness, like the sentence Ozick calls Anne’s most celebrated—and misused—slathered on Anne Frank posters and postcards worldwide. It reads: “I still believe, in spite of everything, that people are truly good at heart.” Why is she remembered for this line, Ozick wonders, rather than the sentence she wrote three weeks before she was sent to Westerbork: “I see the world being slowly transformed into a wilderness, I hear the approaching thunder that, one day, will destroy us too, I feel the suffering of millions.” Ultimately, Anne’s story doesn’t end in the attic, where her diary stops. Her life ends like millions of others whose lives ended in the camps, Ozick writes:

Anne and Margot were dispatched to Bergen-Belsen. Margot was the first to succumb. A survivor recalled that she fell dead to the ground from the wooden slab on which she lay, eaten by lice, and that Anne, heartbroken and skeletal, naked under a bit of rag, died a day or two later.

Of course, I wasn’t thinking about Anne’s final days either when I hid under the pingpong table in 1980. I got a sense of Anne’s increasing despair later, when I read her diary again and then Mueller’s biography and learned what happened once she got to Bergen-Belsen. Though I had nothing really to be scared of in 1980, I’m sure I must have been trying naively to relate to what happened to Anne, or at least to try to understand it. My obsession took hold then and never left.

Nathan Englander writes about a different kind of obsession with Anne Frank in his 2011 short story, “What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank.” The characters describe what they call the “Righteous Gentile Game,” or the “Who Will Hide Me Game.” It’s just what they do, the character Deb says, when they talk about Anne Frank. “[I]n the event of an American Holocaust,” she says, “we sometimes talk about which of our Christian friends would hide us.” Ever since Englander’s story came out, I’ve called this the Anne Frank Game, and I play it often though I’m not proud of it, most recently at an English department meeting at the high school where I teach. I played the game by myself, while my department chair droned on about Common Core standards and upcoming evaluations. Out of 37 English teachers—there are 40, but Jews are exempt, according to my rules—I came up with three colleagues I thought might hide me. I have no other rules, really, it seems, because I never get past the question of who would hide me. The “who” is the game. I suppose there should be more guidelines, such as: Do they get more points for hiding me longer than others? What kind of food would they bring me? Would I have a toilet I could use? And, of course: What happens after the war? In my English department, I was on the fence about one of the three; he’d say he would hide me, but his “yes” would be more about his need to appear politically correct. When it came down to it, I didn’t actually think he’d take the risk of keeping me safe in his attic.

My looks also contributed to my obsession with Anne Frank, I’m sure, for I was told often how much I resembled her. This happened a lot as a child, but when I was 22, a stranger, a woman from Belgium, said I looked just like her in the gift shop at the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam. It was 1992, and my father brought me to visit the house. Like millions of others before us, I got the chills as we walked up the steep stairs behind the bookcase. But when I walked into Anne’s room and saw the pictures of the movie stars on the walls—Ginger Rogers, Norma Shearer, the dancer Joyce Vanderveen were just a few—I began to cry. Anne wrote about this in her diary:

Thanks to Father, who had brought my whole collection of picture postcards and movie stars here beforehand, I have been able to treat the walls with a pot of glue and a brush and so turn the entire room into one big picture.

I looked at my father, then, sure he would have done the same for me. When we exited the house onto Prinsengracht Street, my father gave me the map and told me to lead us. I had to learn to find my way, he said. He knew I was shook up, but for him, the best way to deal with my sadness was to teach me to move forward. I discovered that day how to find myself on a map and to get us where we needed to go.

***

The Nazis that came to Evanston in 1980 were not the same Nazi group that applied for a permit to march in Skokie just three years earlier, on May 1, 1977. The leader of the National Socialist Party of America, Frank Collin, chose Skokie for that march because of the large number of Holocaust survivors—thought to be the biggest outside of Israel. According to the Illinois Holocaust Museum, in 1977 about 40,500 of the 70,000 residents of Skokie were Jewish, and around 7,000 of these were Holocaust survivors. A long legal battle followed, resulting in a landmark free-speech decision in which the Nazi group, defended by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), was granted the permit. Ultimately, however, Collin and his group decided not to march in Skokie and chose downtown Chicago instead. When we moved to Evanston in 1979 from Gainesville, Florida, people were still talking about it.

And for some reason I’ve never been able to understand, a couple years before I hid in the basement, my Hebrew teacher with the shimmering green eye shadow had also told my class rumors that Adolf Hitler was alive and living in Africa.

“Why the hell would she tell you that?” my father asked later, when I told him and my mother at dinner one night.

“Honey,” my mother leaned into my father, “just let her talk.”

I don’t know why my teacher disclosed this. But I remember being almost as scared that day as I was in 1980. I did read later claims that Hitler might have lived out his days in Colombia or Argentina, so perhaps my Hebrew teacher was referring to these rumors and got it wrong. I suppose the country where he might have lived doesn’t matter, really, but if she—the adult in charge—was going to tell a bunch of 8-year-olds Hitler was alive, she could have gotten her facts straight.

Despite these fears I had when I was young, or perhaps because of them, I grew up with a strong Jewish identity. I was part of a large thriving Jewish community along Chicago’s North Shore. I belonged to a progressive, socialist summer camp whose ideals were rooted in Zionism. The Holocaust was over. In high school, my Jewish friends and I wore stickers every year on Holocaust Remembrance Day that said, “Never Again,” as we hugged each other tight. I’m sure at the time we believed the slogan to be true. We were strong and confident—we were not victims. We would never be like lambs to the slaughter.

As my Jewish identity deepened, so did my love for Israel. Of course, it began as a child, finger painting the tiny country—claiming and occupying the land in childlike terms—in Sunday school, but as a teenager, it blossomed. In 1986, when I was 16, I got my first job at the local kosher butcher, Kosher City, in Skokie, to save money for my first trip to Israel. My parents said I needed to help pay for the eight-week program. The owner paid me $3.25 an hour, cash, under the table, and every Sunday for four hours I cut heads off fish and sliced cheese by the pound. My parents led me to believe that they couldn’t have paid for the trip to Israel without the $300 I earned by myself.

Arriving in Israel, I fell in love, and a few years later, in my 20s, I moved to Jerusalem to attend graduate school. Though I never made aliyah, I pretended I was Israeli when it was convenient for me to do so. I used the land as a playground. But my mystified love for the country was always different than daily life. My attempts to permeate the society were limited. I hadn’t served in the army. My Hebrew was sufficient but not sophisticated. I didn’t really like Israelis all that much; I just didn’t seem to have that much in common with them.

The year I lived in the Idelson dorm, on the Mt. Scopus campus, most Israelis went home on the weekends—a reality vastly different from my college experience in Madison, Wisconsin, a few years earlier, where everyone was drunk on the weekends. So I hung out with others who, like me, had come to Israel from somewhere else. I was no sabra; I was a faux expat on a student visa: a diaspora Jew to the core. I played darts at Champs, the bar full of other faux expats on Yoel Solomon Street near Zion Square. I had more in common with Khalil, the Palestinian American I met there, than Israelis in my graduate classes. Khalil and I dated for a year, and together, we used the country as the backdrop for our experimental 20s, drinking and smoking our way through the West Bank. It seems that I had become more comfortable with the finger-painted blurry Israel I had created when I was 10 on the day of the Nazi march than the large real map across the classroom. I needed Israel misshapen and distorted, colored outside of the lines, I suppose; which is to say, I would long for it and define it in my own terms, but never fully penetrate it, and then return, and leave again.

But even the most official maps are blurry and distorted. After dating Khalil, I remembered that the large map in my Sunday school classroom, for example, highlighted the Jewish-Israeli cities, not Palestinian ones. The words Judea and Samaria spread across what I’d later learn was also called the West Bank. When I was with Khalil, he drove me through Ramallah and Bethlehem—two major Palestinian cities I didn’t know anything about. Later, on subsequent trips when I’d return to Israel, I visited other Palestinian cities, too: Nablus, Nazareth, Jenin, and Tulkarm.

Once I finished my master’s degree in 1996, I got an apartment in Chicago and bought a shower-curtain map of the world. There, in the Middle East, painted in pink, purple, and green was Lebanon, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Syria. Israel was in the middle but there was no Palestine. I took my black sharpie and, after putting a slash mark next to Israel, wrote the word Palestine. It was a feeble step toward activism, one that only I and a handful of others who used my pitiable bathroom would ever see.

In the winter of 2010, when I was 40, I went back to Israel/Palestine again. This time, it was with 20 other Jews on a dual-narrative tour that exposed us to both the Israeli and Palestinian perspectives. We traveled together for 10 days. One night we stayed in Deheishe, the refugee camp established in 1949 just south of Bethlehem, with Palestinian families who had agreed to host us. During dinner, we sat on large square pillows on the floor as our hosts served us warm pita and small plates of hummus, baba ganoush, tahini with parsley, za’atar with olive oil, chicken with rice. We smoked hookah afterward and drank mint tea. The matriarch, Safa, said she doesn’t “ever try to leave Bethlehem anymore because I’m never let through the checkpoints.” Her children told us stories of Israeli soldiers kicking them, invading the refugee camp in the middle of the night. “Incursions,” their mother said.

To me, Israeli soldiers had been nothing but objects of American Jewish girls’ flirty behavior. To Palestinians, they are the enforcers of the ongoing military occupation. At age 16 on my first trip, my friends dared me to make out with an Israeli soldier and ask him for his shirt. I approached one in the Russian Compound in Jerusalem outside a bar. The soldier had black curly hair and green eyes. As we made out, he pushed me against the brick wall and I felt his M16 press against my thigh. He gave me his shirt. In Deheishe, Safa’s son told a story of watching an Israeli soldier point his M16 at his father’s face. Then the soldier kicked his father in the shin until it bled. Her husband, Safa told us, was humiliated in front of his children.

After hearing I was an English teacher, one of the daughters brought her English books out and showed me a passage she was reading. It was on the use of computer technology in the classroom. One of the pages had a map. The daughter pointed to Deheishe. “We live here,” she said. Like my father, I wanted to take her outside and empower her to find her way. But it was getting late, and, besides, she already knew her way around the refugee camp.

In the evening, as the dusk rolled into the camp, we went onto the roof and watched the rose and orange colors dance across the sky. We saw lights flicker above us from the neighboring hills—all Israeli settlements. Later that night, four of us women from the trip slept on the floor in a small, square room the father had built on top of their bedroom. We had thin individual mattresses and lots of blankets, but it was still cold. One woman read on her iPad. The other two slept.

I finally fell asleep, too, but I awoke in the middle of the night and was disoriented. I was thinking about the Israeli soldiers’ incursions into the refugee camp the family had told us about that evening, and making out with the Israeli soldier when I was 16. I began to feel sick. My mind spun back decades to when I hid from the Nazis in my basement when I was 10 after fingering my private distorted version of Israel. But I was 40 now, and I felt ashamed for the jumps my brain was taking. I was in a Palestinian refugee camp staying with people who were forced here in 1949, and if things continue the way they are, they’ll never get to leave.

I was up most of the night at Deheishe, and I bit my nails until they bled. At one point I played the Anne Frank game. I determined that only one of the three women who lay on the floor would hide me if there was another Holocaust—the one with the iPad. Outside, it was quiet. The children in the house had been asleep for hours. Earlier, I had heard the sound of pots and pans in the kitchen, but the noise had long dissipated. When I was still, I began to feel some warmth, but I felt alone. I looked at my palm and, under the blanket where no one could see, I drew an imaginary line from Jerusalem to Tel Aviv, thinking of all the places and things in between that I’ve missed.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Liz Rose Shulman is a writer and teacher living in Chicago.