The full Tablet series featuring Paul Berman’s original three-part essay on the state of the contemporary Left, along with responses to Berman from writers across the political spectrum, is collected here.

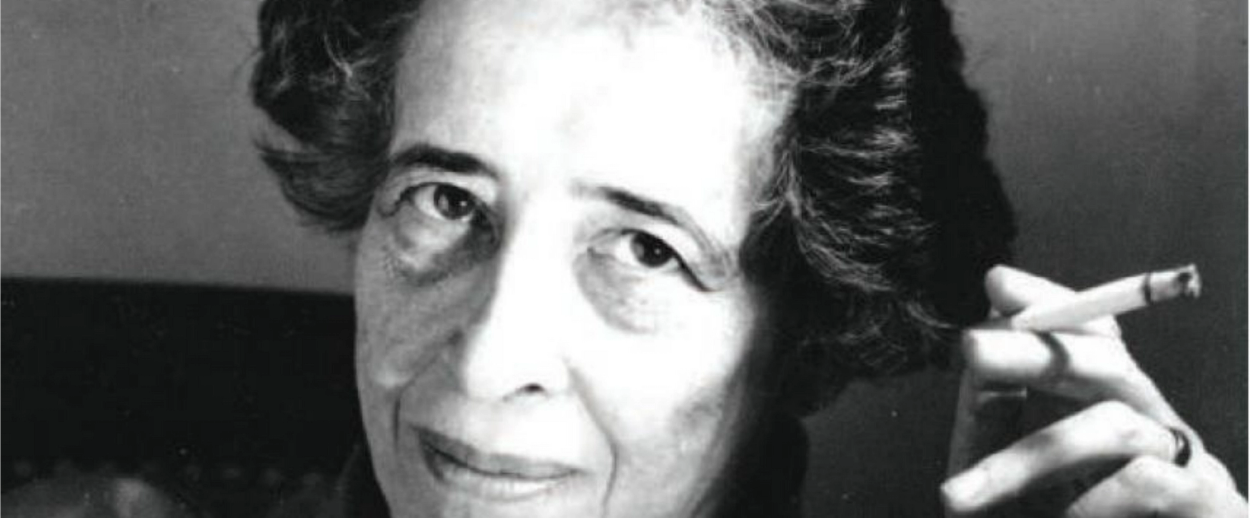

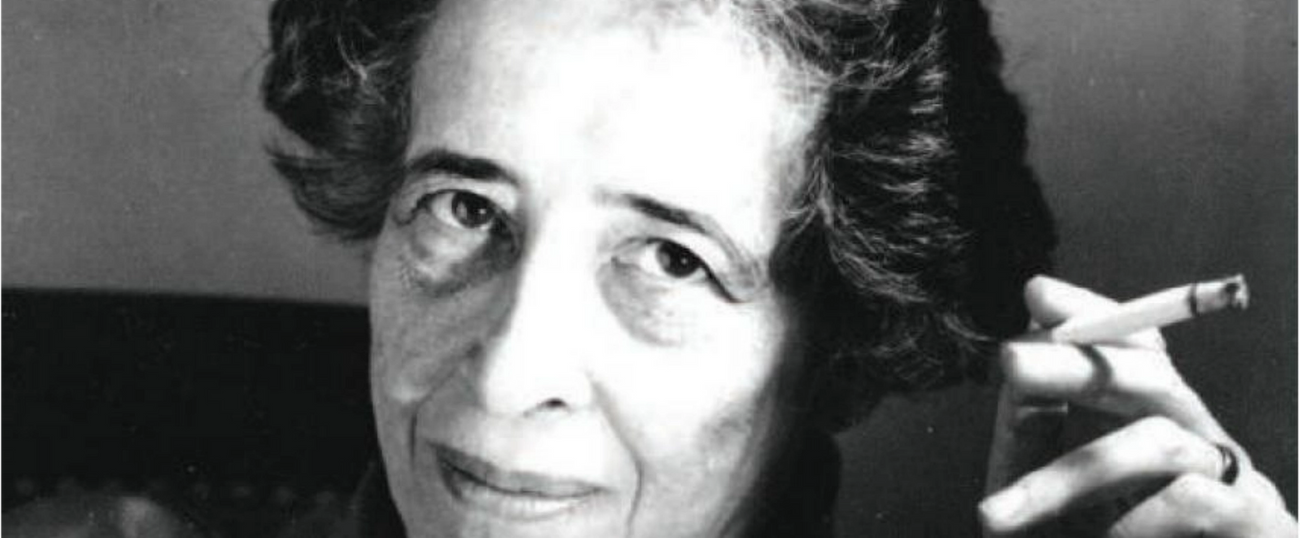

If you want to understand American politics today, the single best source might be page 334 of Hannah Arendt’s masterpiece, The Origins of Totalitarianism. No, that’s not because Donald Trump is plotting a fascist coup. He’s not nearly smart enough to pull it off. Even if he were, Arendt’s description of life under totalitarian rule is easily the least insightful part of the book. Her real genius was for explaining why liberal societies fall part. It’s a question that should be on all of our minds.

Now, on to page 334. After running through a brief history of modern Europe, Arendt’s narrative brings her to one of the most puzzling questions of the interwar period: Why were vulgar demagogues peddling ridiculous doctrines able to turn millions of people against the liberal order? She had, by then, already discussed the psychology of what she sniffily referred to as “the mob,” and now turned her attention to totalitarianism’s attractions for the elite. What especially interested Arendt, who turned 27 the year Hitler became chancellor of Germany, was its appeal for younger intellectuals.

Her answer centered on the failings of the status quo. “What the defenders of liberalism and humanism overlook,” she observed, was that it had become “easier to accept patently absurd propositions than the old truths which had become pious banalities.” Why was that? Well, people had eyes. They could see that elites who proclaimed themselves champions of civilization were “parading publicly virtues which [they] not only did not possess in private and business life, but actually held in contempt.” Everybody knew the whole thing was a joke, except for the great men who bought into their own propaganda. Confronted with this hypocrisy, “it seemed revolutionary to admit cruelty, disregard of human values, and general amorality because this at least destroyed the duplicity upon which the existing society seemed to rest.” Sure, the alternative was farcical, but at least everyone would be able to stop mouthing the same old lies, and that offered a kind of liberation.

I couldn’t help thinking of Arendt’s diagnosis while I was reading Paul Berman’s call for a patriotic leftism. Berman isn’t alone in wanting the American left to stake a claim on its country. The historian Jefferson Cowie recently issued a similar plea in TheNew York Times, while leading Resistance intellectual Yascha Mounk has urged liberals to embrace the cause. John Judis, one of the most insightful political journalists around, just published an entire book on the subject.

Yet Berman’s variation on this theme is especially forceful. He writes with evident admiration of Walt Whitman’s belief in the United States “as a kind of religion, except without a theology—a secular and poetic religion of democracy.” Like Whitman before him, Berman is out to make converts. He wants a movement that sees American principles and left-wing principles as one and the same—a politics that recognizes “the grandeur of American civilization” and sees “something large and thrilling and deep in the patriotic idea.”

To which I can only respond: Do we have to? According to the left-patriots, the answer is obvious. As Cowie put it in the Times, “One of the core lessons of Trumpian politics is that Americans are starved for a meaningful politics of what it means to be American.” But Trump’s nationalism is a strange thing. When he was asked about American exceptionalism in 2015, Trump replied:

I don’t like the term. I’ll be honest with you. . . . Because essentially we’re saying we’re more outstanding than you. “By the way, you’ve been eating our lunch for the last 20 years, but we’re more exceptional than you.” I don’t like the term. I never liked it. When I see these politicians get up [and say], “the American exceptionalism”—we’re dying. We owe 18 trillion in debt. I’d like to make us exceptional.

Trying to divine constant themes in Trump’s thought is almost always a doomed endeavor, and he’s spat out plenty of bromides about national greatness over the years, but America’s unexceptional, even fallen, nature, remains a consistent refrain even now that he’s in the White House. “You think our country’s so innocent?,” he asked Bill O’Reilly in 2017, during an exchange over Vladimir Putin. Trump’s a nationalist, of course; that’s what all the America First talk is about. But he doesn’t often refer to the standard items in the patriot’s checklist—the genius of the Founders, the glories of the Constitution, the wisdom of Washington/Jefferson/Lincoln/etc. This is a distinctly unpatriotic nationalism, and his supporters love it.

Contrast that with Hillary Clinton’s approach in 2016. While Trump was saying that the American dream was dead, she was draping herself in the flag. The Democratic National Convention was a festival of Americanism, right up to an acceptance speech quoting from three of her favorite sources: her mother, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and the musical Hamilton. “In the end it comes down to what Donald Trump doesn’t get,” she said: “America is great—because America is good.” Nobody would mistake Clinton’s rhetoric for the serious, reflective patriotism Berman yearns for. But her campaign was premised on the notion that Trump was a singular departure from the country’s history—or, she might have called it, the grandeur of American civilization.

Does anyone still think that America is great because America is good? Did Clinton ever really buy it? It’s hard to believe. A nation filled with deplorables should have a hard time ranking high on either the greatness or goodness scales. And she’s one of the winners in American life—not in the Electoral College, of course, but a multimillion-dollar bank account is a fine silver medal.

It could be that my problem is personal. I’m a historian, and we’re trained to be killjoys. Grandeur doesn’t strike me as a fitting description for the nation that I’ve devoted my career to studying, and that I’ve lived in almost my entire life. The country I know is a mix of the glorious, the mundane, and the terrible—just like everywhere else in the world. The balance might be better here than in most places, but we’re not grading on a curve.

Put aside the needless suffering caused by the familiar litany of ills—poverty, racism, sexism, a psychotic gun culture, an opioid epidemic, a gluttonous one percent, endless war—and focus on the everyday cruelties that anyone who grew up, like me, in mass-produced suburbia will recognize: the petty authoritarianism of the suburban dad demanding to speak to the manager at Applebee’s; the wine-mom drowning her frustrations in Chardonnay; the teenagers making everyone else miserable while they’re waiting to escape. We’re supposed to create a religion out of that?

None of this is building up to a denunciation of Amerikkka. Both extremes of the debate over patriotism belong to an earlier era—to the 1960s and 1970s when baby boomers reacting against the hypernationalism of the Greatest Generation veered headlong into the opposite direction. A country where median incomes are stagnant, life expectancy is falling, and Donald Trump is president has better things to worry about. If America is a religion, this is what a crisis of faith looks like.

But can’t it just be a country? Instead of writing hymns to American greatness, we could devote our energy to passing an agenda that would deal with the issues we’re actually facing: universal health care, a jobs guarantee, tuition-free college education, and whatever else it takes to give our lives a decent measure of economic security and break the 1 percent’s death grip on democracy. Plus we have to stop the planet from melting.

There’s a long way to go before we get there. I keep coming back to Arendt because she tells us how to get started. We’re stuck in the same cycle that she saw in interwar Europe. Trump sells the patently absurd, and Democrats respond with clichés that not even they believe in. Coming up with nobler lies isn’t going to help. Telling the truth might.