China Queen Dianne Feinstein Used Her Senate Power to Push Most-Favored-Nation Status for the CCP’s Corrupt Dictatorship. Why?

How an American elite subscribed to the unproven theory that business with the Chinese Communist Party is good for America

In November of last year, a glittering array of world statesmen gathered in Beijing for Bloomberg’s New Economy Forum. At the top of the list was former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. He was worried. With China skeptic President Donald Trump imposing huge tariffs on Chinese goods, the most famous living diplomat was concerned about the future of the United States’ relationship with China’s Communist government. Trump’s actions, said Kissinger, had landed the two sides in “the foothills of a Cold War.”

That seemed unlikely, according to former U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson. “China will be a big part of the global financial picture in decades to come,” said the former George W. Bush cabinet member. And then, Paulson made an off-handed remark that may turn out to be the most unintentionally prescient observation of the 21st century: “Unless something goes terribly wrong in China,” said Paulson, “no other nation will wish to decouple from its financial markets.”

Five months later, the wisdom of exporting millions of American manufacturing jobs and large parts of critical supply chains for everything from medication to ventilators to a hostile overseas power is looking ever more questionable, as a novel pathogen of Chinese origin has wreaked havoc on the American economy and locked the entire country indoors. In retrospect, Richard M. Nixon’s 1972 meeting with Mao Zedong marked not only the opening of China, but also a nearly 50-year delusion about the nature of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and its compatibility with America’s own economy and society.

For Kissinger, as for others, there was money at stake as well. “Kissinger was completely ‘played’ by the party,” says one experienced D.C. China hand. “His consulting enterprise, Kissinger Associates, built their ‘business’ around enabling the Chinese Communist Party and convincing Western business leaders that they needed to leave their ‘business judgment’ at the border and simply accept the party’s conditions as the price of entry into the China market.”

The links between leading American politicians and companies and the Chinese leadership are now likely to come under increased scrutiny.

First on that list of those deserving of close attention is the senior U.S. senator from California, Dianne Feinstein—a longtime member of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence—who briefly made headlines a few years ago when reports surfaced that she had been forced to fire a longtime aide after learning from the FBI that he had been recruited on behalf of the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

No one represents the marriage of American policy toward China and doing business with the PRC better than Feinstein. Her promotion of trade with China to advance the interests of her constituents turned into apologetics on behalf of the Communist Party, as it aided her political ascent and augmented her husband’s portfolio. In October, USA Today listed Feinstein as the sixth-richest member of Congress, with a net worth of $58.5 million—a sum that vastly understates her actual wealth. Richard Blum, her husband, is himself worth at least another $1 billion.

When Feinstein was first elected to the Senate in 1992, Blum’s interests in China amounted to less than $500,000. She was named to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 1995 and by 1997, according to the Los Angeles Times, “Blum’s interest had grown to between $500,001 and $1 million.”

In 1994, Blum’s company, Blum Capital, had entered a joint venture to found Newbridge Capital, specializing in emerging markets, including Asia. Blum said in 1997 that less than 2% of the approximately $1.5 billion that his firm managed was committed to China. He held a $300 million stake in Northwest Airlines when it operated the only nonstop service from the United States to cities in China. In 2002, Newbridge was negotiating to acquire 20% of Shenzhen Development Bank. After some rough seas, it paid $145 million for an 18% share two years later, marking the first time a Chinese bank came under control of a foreign entity.

Feinstein says that Blum’s business in China had no effect on her foreign policy or trade positions regarding the country. “We have built a firewall,” she said of her relationship with her husband. “That firewall has stood us in good stead.”

Yet the record shows that the marriage between Blum’s business and Feinstein’s political career is a very close one. Journalists from Feinstein’s home state’s two largest media markets, Los Angeles and San Francisco, covered that relationship thoroughly and often quite skeptically throughout the 1990s and early 2000s. The fact that relationships that should have come under serious scrutiny have rarely been portrayed in anything other than a favorable light—the New Yorker breathlessly reported in a 2015 profile that China’s former President Jiang Zemin had spent Thanksgiving as a guest at the Blum-Feinstein home in San Francisco—reveals the extent to which the American elite has subscribed wholesale to the unproven theory that business with the Chinese Communist Party was good for America.

What began as faith in the inherent goodness of relations between the United States and China eventually transformed into something dark, crude, and cynical. As Benjamin Weingarten recently reported, Feinstein has repeatedly criticized Trump’s tariffs on China, turning her advocacy for the Communist Chinese government into an instrument of domestic political warfare—and cementing a pro-China policy as a foreign policy touchstone to rival support for the JCPOA, President Obama’s Iran deal, within the Democratic Party.

Dianne Feinstein first visited Shanghai in 1978, shortly after the United States and China opened diplomatic ties. San Francisco’s newly elected first woman mayor struck up a friendship with her counterpart, Jiang Zemin, who was mayor of Shanghai at the time. Under their guidance, Shanghai, China’s leading industrial city, and San Francisco, home to one of America’s largest Chinese immigrant communities, struck up a sister-city relationship. The two siblings did well by each other.

“China made friends first,” Feinstein told the New Yorker in 2015, “and then they did business with their friends.” Feinstein considers Jiang a “good friend.” Feinstein also spoke about how she and Jiang danced together. Then they started to make money. In the mid-’80s, a firm in which Blum invested struck a $17 million deal with a state-owned business for a retail and residential complex outside Shanghai.

In 1989, Jiang became general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party. Three years later Feinstein was first elected to the Senate. Serving two of the largest Chinese diasporas in the United States—the San Francisco/Oakland/San Jose area (629,243) and the greater Los Angeles area (566,968)—Feinstein respected the wishes of many, but hardly all, of the Golden State’s Chinese Americans who wanted warm ties with their ancestral homeland. More importantly, her longstanding ties to senior Chinese Communist Party officials advanced the financial interests of her constituents. It is because of California’s trade relationship with China that the state is the world’s fifth-largest economy.

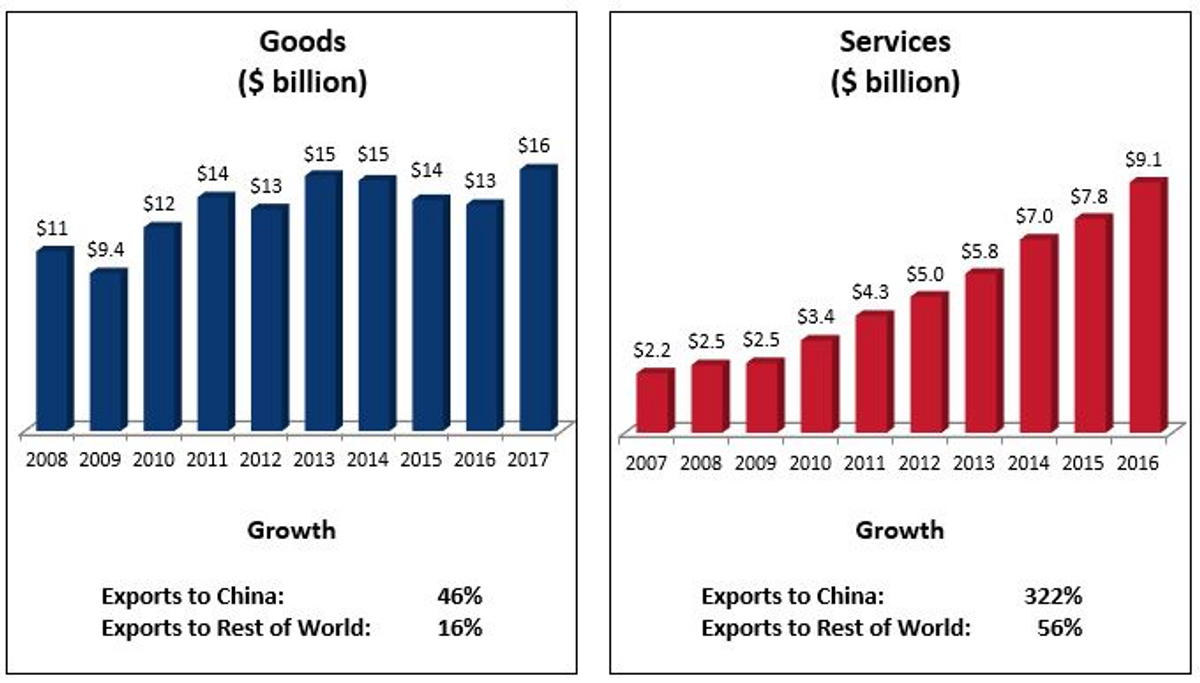

In 2015, China accounted for 35.1% of all imports to California. In 2017 California exported $15.6 billion in goods and another $9.1 billion in services to China. The top exported goods were motor vehicles, scrap products, industrial machinery, navigational and measuring instruments, and semiconductors and components. The top exported services included travel, education, royalties from industrial processes, film and TV distribution, and computer software. In 2018, total California trade with China topped $175 billion, with California exporting $16.3 billion worth of goods and services, and importing $161.2 billion, leaving it with a $144.9 billion trade deficit with China. From January to April of 2019 alone, China exported $39 billion, or more than twice what California exported the entire year, at $15.85 billion.

And the relationship benefited Feinstein personally. In 1993, Jiang became president of China and invited Feinstein and Blum to Beijing to meet with party leadership. According to a 1994 Los Angeles Times story, Blum was planning to bundle $2 million to $3 million of his own with another $150 million from other investors to invest in state-owned enterprises, including telecommunications equipment.

Feinstein said at the time that Blum’s economic interest in China was “news to me.” The couple denied that his business in China profited from her then 15-year friendship with the president of China. “He is in San Francisco running his business, I am in Washington being a United States senator, and they are two separate things,” Feinstein told reporters. “I don’t know how I can prove it to people like you. Maybe I get divorced. Maybe that is what you want.”

There’s a logic to Feinstein’s self-pity—she was being singled out for doing what everyone else was also doing, or dreamed of doing. Taking a piece of the action was good for America, the winners told themselves. Business with China kept the peace. It was a central tenet of the post-Cold War order—with mutual financial interests at stake, no one makes war against their trade partners.

Nor were Feinstein and Blum alone in their wholesale profiteering from the U.S.-China relationship. The idea that there was something inherently virtuous about helping Chinese companies make money at the expense of their American rivals became so prevalent in Washington that it barely raised eyebrows when one-time Democratic vice-presidential candidate Joe Lieberman, whose political brand was his supposedly unimpeachable rectitude, joined former Senate colleague Norm Coleman, a Republican, to lobby for ZTE, a Chinese telecom firm with reported ties to the Chinese intelligence services and military.

What makes this story even uglier is that American policymakers knew how the People’s Republic of China was targeting American companies: The same month that Lieberman signed on with a CCP telecom, the Justice Department asked Canadian authorities to detain the chief financial officer of another, Huawei. The daughter of the company’s founder, Meng Wanzhou, was named as a defendant in a case charging Huawei with racketeering and conspiracy to steal trade secrets. A month later, grand juries in New York and Washington state indicted Huawei for stealing intellectual property from T-Mobile.

And yet, American officials have continued to sell their talents and contacts to Beijing. In April 2019, the same month that U.S. intelligence reported that Huawei was funded by Chinese state security, the firm hired the Obama administration’s former director for cybersecurity, Samir Jain. “This is not good, or acceptable,” Trump tweeted in response to the news. The Justice Department did not answer emails asking if Jain still holds a security clearance.

Kissinger’s 1972 opening of China is typically seen as a geostrategic masterstroke whose purpose was to further divide China from its rival communist power, the even more threatening Soviet Union. The reality is that Kissinger’s vision of China as America’s bride-in-waiting derived from much older ideas about the country.

More than a hundred years before, China’s defeat at the hands of France and Great Britain opened the country to foreign trade as well as foreign visitors, most notably Protestant missionaries. Thousands of American families joined their British counterparts in the Far East; fertile ground, they believed, for spreading the Gospel. These missionary pioneers would come to shape American foreign policy and attitudes toward China for generations to come, as their offspring filled positions of influence in the government, academia, and media. Henry Luce, for instance, the founder and editor-in-chief of Time magazine, the 20th century’s most influential publication, was raised in China to missionary parents.

Long after the 1949 communist revolution, Luce continued to wage a rearguard action, joined by other reactionaries like Sen. Joseph McCarthy, who complained that President Harry Truman’s State Department and the liberal establishment had “lost” China to the “Reds.” It’s true that some senior American officials preferred the communists to the ostensibly pro-Western nationalists, who were cruel and corrupt, but the reality is that no one “lost” China. Luce’s line of argument is derived from the same fiction that motivated his parents and their devout associates—China was theirs for the taking. Mao’s revolution should have made clear that Chinese politics and society, like those of every country, are moved primarily by its own internal forces.

Yet the conviction that China was ripe to be remade in America’s image continued to form the thinking of the American policy establishment. Their optimism was not wholly misplaced. America’s use of economic development to drive political liberalization had shown repeated successes in the post-WWII period. “It’s the strategy we used most consistently since the end of WWII,” says Matthew Turpin, who served as China director for Trump’s National Security Council staff in 2018-19, and held a similar position at the Pentagon under the Obama administration between 2013 and 2017.

“We used it with postwar Italy and Germany and Japan in the 1940s. In the ‘70s we used it with Spain, and in the ‘80s we used it with South Korea and Taiwan. And we used that approach after the fall of the Berlin Wall with the countries of Eastern Europe. The strategy has a logic to it. So, we thought the same with China. Building China’s economy and accustoming its leadership to the peace that is a natural consequence of prosperity would lead to political liberalization.”

The problem is that Chinese leadership saw through America’s strategy. You didn’t need to be steeped in Marxist doctrine to see that the capitalists understood China as an untapped resource just waiting to be exploited. China was a self-baiting trap and all Mao and his successors had to do was wait for the Americans to wander in.

If anyone should have understood the darker currents running through humanity, it was America’s 41st president, George H. W. Bush. A WWII Navy pilot who lost men in the Pacific, Bush had served as U.S. ambassador to China and also as director of the CIA before becoming vice president. In those roles, he came to know China well, while overseeing Cold War proxy fights and operations that cost many thousands of lives and decided the fate of hundreds of millions more.

But for whatever reasons—his WASP heritage, the primacy of Cold War rivalry with the Soviet Union, or the sense that the world was owed a respite after so much bloodshed and that it was his historical role to usher in a post-Cold War era of peace—Bush was determined to see China as a partner rather than a rival. “I see a world of open borders, open trade and, most importantly, open minds,” he told the U.N. According to Bush, the new order is “a world that celebrates the common heritage that belongs to all the world’s people, taking pride not just in hometown or homeland but in humanity itself.”

For their part, the Chinese knew Bush and liked him—and liked Republicans. They had evidence that the GOP meddled less than the Democrats in the affairs of foreigners. After all, Kissinger had “opened” Beijing during the murderous mass purges known as the Cultural Revolution without batting an eye.

On the other hand, the Chinese were worried about Bush’s 1992 challenger, Bill Clinton. On the campaign trail, Clinton had linked trade with China to its human rights record.

But Feinstein wasn’t about to let this become an obstacle.

As the U.S. Senate deliberated whether to withdraw most-favored-nation trade status from China in 1994 because of human rights abuses, Feinstein—then a freshman senator—established herself as a strong advocate of closer ties. Expressing disapproval of Beijing, she argued, would be “counterproductive.” Punitive measures would only “inflame Beijing’s insecurities” and halt reform.

President Clinton came to see it the same way. In May 1994, he “de-linked” trade policy and human rights. “To those who argue that in view of China’s human rights abuses we should revoke MFN status,” said Clinton, “let me ask you the same question that I have asked myself over and over these last few weeks as I have studied this issue and consulted people of both parties who have had experience with China over many decades. Will we do more to advance the cause of human rights if China is isolated or if our nations are engaged in a growing web of political and economic cooperation and contacts?”

That American officials expressed concern for human rights in China and the 1.4 billion people living under a communist regime was, and still is, important. Yet the debate over what was actually best for China came at the expense of obscuring the issue that should have been foremost on the minds of American lawmakers—what was best for working Americans, and for the security of their own country. In 1993, China had exported $31 billion worth of goods to the United States compared to $8 billion going the other way. In other words, even with the United States running a trade deficit of $23 billion, there was almost no one making the case for the American work force.

Feinstein in particular was making the exact opposite argument. In a 1996 editorial, she wrote: “Tying most-favored-nation to improvement in human rights is ineffective at best and counterproductive at worst. Revoking the trade status would be seen by China as the United States promulgating a complete break in Sino-American relations, putting in grave danger U.S. strategic interests in Asia.”

Feinstein explained that Americans needed to be patient:

Just 30 years ago, China was engaged in the massive upheaval of the Cultural Revolution and Great Leap Forward, during which 20 million Chinese were either killed or imprisoned. Human rights were at their lowest point. Since then, the positive changes in China have been dramatic. Chinese society continues to open up with looser ideological controls, freer access to outside sources of information and increased media reporting. More people in China vote for their leadership on the local level than do Americans.

That last line is especially illustrative. Nearly the entire American establishment had convinced itself that treating the PRC like a normal country was a sign of virtue. We are all one people under the same sun, engaged in commerce with our fellow man: Who’s to say that the Chinese are not in fact more virtuous than we are? It takes a rare kind of contempt to push propaganda on American voters and tell them they’re less civic-minded than the subjects of the Chinese Communist Party.

Feinstein made a habit in fact of comparing the PRC to the United States to the advantage of the former and the detriment of her own country. She called for a commission of comparative human rights looking at China and America and studying, for instance, “the success and failures [of] both Tiananmen Square and Kent State.” Ohio National Guardsmen killed four students at Kent State in a 1970 anti-Vietnam war protest, an act that was widely condemned at all levels of American society. In 1989, the CCP’s People’s Liberation Army deliberately killed hundreds, if not thousands, of students in the middle of Beijing in order to maintain its own grip on power.

Feinstein talked to her friend Jiang about Tiananmen soon after the massacre. “China had no local police,” Feinstein said that Jiang told her. She was messaging on behalf of the CCP. “It was just the PLA. And no local police that had crowd control. So, hence the tanks ... But that’s the past. One learns from the past. You don’t repeat it. I think China has learned a lesson.” That sounds like a lot to swallow even for a committed advocate of the ruling party—let alone a U.S. senator.

According to reports that surfaced in 2018, Feinstein had employed a staffer who had been recruited by Chinese intelligence. Despite her sensitive position and the staffer’s many years of service, she brushed off the accusation. “He never had access to classified or sensitive information or legislative matters,” said Feinstein. She was named to the Senate Intelligence Committee in 2001, and became chair in 2009, giving her access to America’s most closely guarded secrets.

Charges were never filed against the staffer. Feinstein fired him around 2013, after he’d worked for her for 20 years—or starting around the time her friend Jiang became president.

Nor was this the only time the Chinese government targeted Feinstein. In 1997, she was warned by the FBI that the Chinese might try to push money into her campaign. She said she had “no reason to believe” that the CCP had actually contributed to her campaign. “None whatsoever.”

She had a point. Why would the CCP waste money on her campaign when it was already in business with her husband?

Two years after Blum had co-founded Newbridge Capital, an “emerging markets private equity fund” in 1994, Newbridge acquired a 24% stake in a state-owned enterprise producing iron used in making cars for $23 million. The deal was initiated by an investment company run by a former official from the state-owned investment company CITIC who was also an ex-vice minister of petroleum. Newbridge also invested $14 million for a 24% stake in a food and beverage company run by another former CITIC executive.

Feinstein said that her husband never sought to exploit her access to increase his opportunities in China. On a January 1996 trip to China, Blum and Feinstein went to dinner with Jiang. They dined in the room where Mao died.

“We were told that we were the first foreigners to see his bedroom and the swimming pool,” said Feinstein. She said her “husband has never discussed business with Jiang Zemin, never would, never has.” Of course, the fact that he was having dinner with the Chinese leader and visiting his bedroom and swimming pool would have been more than enough for lower-ranking Chinese officials to know exactly where Blum stood with their bosses.

Blum said that he’s also a “close personal friend” of the Dalai Lama, and claims to have served as a “liaison” between the holy man seeking Tibetan independence from Communist China and the Beijing government. Meanwhile, Chinese repression inside Tibet has steadily increased for the past two decades.

After the 1997 FBI briefing, Feinstein expressed her frustration to the press about accusations that she was being manipulated by the Chinese. “If there is credible evidence,” she said, “‘tell me what it is. Enable me to protect myself. That’s the job of the FBI.” According to her, none of the FBI agents “told me where or when or how or what to look for.”

In 2000, Feinstein achieved her longtime policy goal when Congress conferred permanent most-favored-nation status on China. The Senate voted in favor with 83 yeas, including Joe Biden. The Republican governor of Texas and presumptive GOP candidate for president praised the bill: “Passage of this legislation will mean a stronger American economy, as well as more opportunity for liberty and freedom in China,” said future President George W. Bush. And so, the deal was done.

In retrospect, some American politicians on the right now admit that their assumptions about the PRC were horribly mistaken. “We thought getting them into a rules-based system would gradually permeate their culture and that’d be a big step in the right direction,” said Newt Gingrich, author of the 2019 book Trump vs. China: America’s Greatest Challenge. “That was all wrong,” said the former speaker of the House.

With the coronavirus having put America on hold, it is worthwhile trying to figure out how and why we got it so wrong. The United States’ political and business elites told themselves that the new breed of Chinese communists were interested in money, just like capitalists. That fiction required American officials to ignore what they should have observed during the Cold War struggle against Soviet communism: Moscow apparatchiks and their Iron Curtain courtiers very much enjoyed the luxuries that money afforded them, like Western-made shoes and tailored suits, access to fresh vegetables and Swiss bank accounts, etc. The politburo confiscated private wealth not on behalf of the proletariat, but to enrich themselves.

The money pouring in from deals with Beijing lubricated America’s ruling classes, who wanted to be seduced—and so they ignored what was obvious about their new partners. What distinguished communists was not in fact their disdain for money or their trenchant critiques of consumer capitalism. Rather, it was their single-minded and paranoid pursuit of power.

By the time Xi Jinping began to consolidate his hold in 2012, it had become clear that Beijing wasn’t interested in joining the liberal international system. What China wanted was for its self-defined sphere of influence to be acknowledged by the United States and expanded throughout Asia. “When Xi came to power,” says Matthew Turpin, “the Chinese offered the U.S. a new form of international relations, which was actually a return to an older form: spheres of influence. The two powers would set norms in their own spheres of influence and show each other mutual respect. The Chinese said, ‘We get Asia, you get the West.’ The Obama administration rightly saw this as a complete rejection of the international system that had kept the peace for decades.”

Australian official John Garnaut, a respected former journalist who spent years reporting from China, explained the CCP’s paranoid worldview in an important speech he delivered in 2019: “The Western conspiracy to infiltrate, subvert and overthrow the People’s Party is not contingent on what any particular Western country thinks or does. It is an equation, a mathematical identity: The CCP exists and therefore it is under attack.”

In April 2013, the party’s Central Committee circulated a “Communique on the Current State of the Ideological Sphere.” Document No. 9, as it came to be called, explained the confrontation with the Washington-led liberal international system in stark terms—China’s enemy, it argued, is the West. Party cadres were required to wage an “intense struggle” against “false trends,” including Western constitutional democracy, human rights, and freedom of speech—especially journalism—which the Communists defined as instruments used to weaken the party.

Xi and his top deputies were right of course. Starting with Mao, Communist Party officials knew what American officials were plotting with their strategy of “peaceful evolution.” What’s important about Document No. 9 is the insight it offers onto the party itself, a self-image drawn in the sharp hues of confrontation. Western liberalism is the party’s nemesis.

Lee Smith is the author of The Permanent Coup: How Enemies Foreign and Domestic Targeted the American President (2020).