An Outsider in Jerusalem

Like a vampire, I fit nowhere in Israel but inside the real and made-up stories of lovers and others. Fifty years after the end of the Six-Day War, a look back at the monsters and myths of youth.

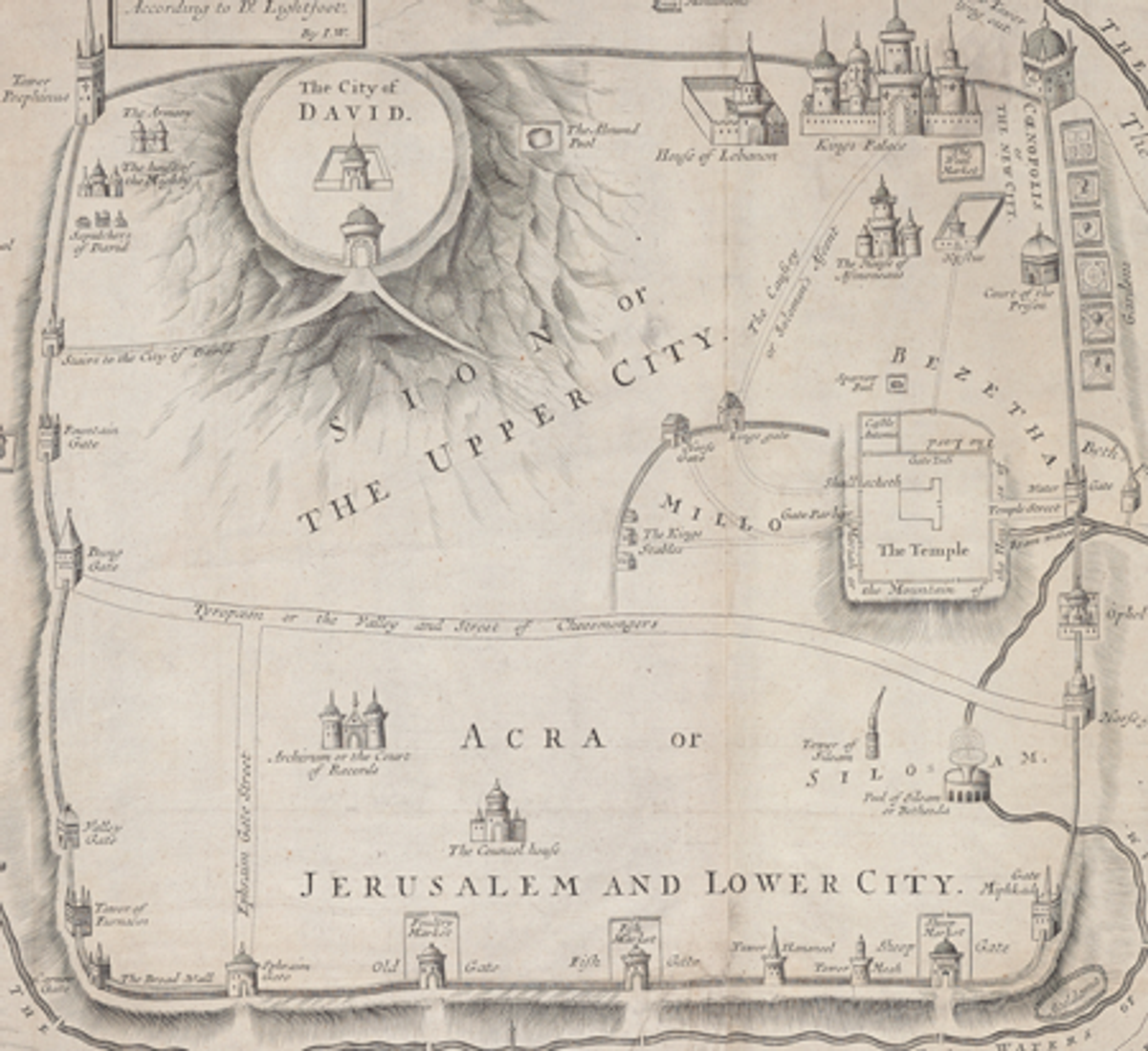

Last week, as I was prepping to teach my 11th-grade English class, I reread the Greek creation myth where Rhea wraps a stone in swaddling clothes, pretending it’s Zeus, whom she’s hidden to protect him from his father, Cronus. In the particular Greek myth I’ll be using with students, the stone Rhea wraps is called an omphalos. In Greek, omphalos means navel or the center of something. When I saw it last week, I realized I hadn’t thought about the word since I was a graduate student in the 1990s at Hebrew University in Jerusalem studying literature. Both Jewish and Christian ancient religious texts consider Jerusalem the geographical and spiritual navel, or omphalos, of the Earth. As early as the second century, Jerusalem was put at the center on cartographic images and called the “navel” of the earth.

A flurry of memories came rushing forward in my mind as I sat my lesson planning aside. Omphalos was also the name of the Hebrew University English department’s literary magazine that existed from 1993-2000. The founding editors called it Omphalos as a nod to this idea of Jerusalem as the “navel” of the world. And we who ran the journal gazed with bravado, a youthful superiority, from high up in the hills of the city, and even higher in the hills of Hebrew University, as we decided what pieces deemed worthy of being published in Omphalos. I was a young Zionist fulfilling my birthright to live and study in Jerusalem, falling in love with the city and its stones and smells. The name of the journal was an hommage, as well, to James Joyce—in one of Stephen Dedalus’s stream-of-consciousness narrations, he says, “Will you be as gods? Gaze in your omphalos.”

In 1994, I was on the editorial committee of Omphalos with other English department students. Weekly, for several months, we would get together and look through submissions and decide whose pieces should go in that year’s magazine. As an editorial team, we agreed on many pieces, most of which over-emphasized the soul, love, and God—seemingly fitting for young students studying literature in Jerusalem. Steve Talmai’s poem, for example, played with the idea of roots and souls. Like most of us, he wrote poems of exaggerated cosmic self-importance. “They say I have lived / have roots growing out of my soul,” he wrote in his poem, “Ghetto.” I could relate. I was deeply in love with the city; the roots deep inside my soul had “come home” when I moved to Jerusalem.

At one of our first Omphalos meetings, we all agreed on a short prose piece by Uri Hershberg, “Before the First Word.” It was a creation myth that pointed to modern problems: “Before the Void could sap its resolve, the voice shouted at nothing in the middle of the uniform nowhere: Let there be light / and that’s when the trouble started.” We liked this piece—though maybe we’d cringe reading it now—because it felt edgy to us in the way it mocked the Bible; how risky to publish this in a literary journal in Jerusalem, we mused. We thought James Joyce would have been proud.

One day, when a new batch of submissions came in, I was particularly struck by a poem titled, “Was Dracula Jewish?” submitted anonymously by someone named “X”:

All I drink is wine

never see the sun shine

Sleep all day.

My roommate is out studying Judaism

and all that far out mysticism

Trying to find a way.

Till dawn I read the greats

smoking too many cigarettes

Just finished Hemingway.

I get my second wind at two-ish

wondering if Dracula was Jewish

I’ll wake up someday.

I was the only one on the editorial committee who liked it. The others thought X’s poem was self-obsessive nonsense. I was outnumbered; X’s poem was quickly tossed into the reject pile. For weeks I thought about the poem and its author. Who was X? Could I have known him? I had assumed—perhaps wrongly—that X was male. The only people I knew who read Hemingway in college were guys.

Could I have walked by X on campus? Maybe he was an American Jew, like me, studying abroad. Or perhaps he had made aliyah, and had been living in Israel for a while now. I wondered what kind of mysticism X’s roommate was studying and, if he had, in fact, as the poem suggested, succeeded in trying to find a way. I tried to think of reasons why X was drinking wine and sleeping in the daytime.

Why did X wonder whether Dracula was Jewish? X wasn’t the first to question Dracula’s potential Jewishness, of course. Many scholars have written about the Jewish—and anti-Semitic—characteristics in Bram Stoker’s Dracula. In her book on the historical changes in the idea of the Gothic monster, Skin Shows: Gothic Horror and the Technology of Monsters, Judith Halberstam argues that “Gothic anti-Semitism portrays the Jew as monster.” Stoker’s Dracula, according to Halberstam, was a product of 19th-century European anti-Semitism. His Dracula was an ambiguous stereotypical Jew, who ultimately reflects “the Jew of anti-Semitism.” Dracula, published in 1897, also coincided with the vast growth of Jewish emigration from Eastern Europe, and many scholars argue that the portrayal of Stoker’s Dracula contributed to the “othering” of Jewish immigrants. “The monster Jew produced by 19th-century anti-Semitism represents fears about race, class, sexuality, and empire,” Halberstam maintains, and “this figure is indeed Gothicized or transformed into an all-purpose monster” in Dracula. Perhaps X felt like an outsider and identified with the vampire, who, as Halberstam argues in her book, “is otherness itself.”

Stoker was not the first to link vampirism with Judaism. It is a stereotype that predates the wave of Jewish immigration that emerged from his novel. Sara Libby Robinson, in her book Blood Will Tell: Vampires as Political Metaphors Before World War I also discusses Bram Stoker’s curious choice to give his Dracula stereotypical Jewish features like his hooked nose, pointed ears, and sharp teeth. Robinson argues that these Jewish stereotypes—which also included vampire metaphors, blood libel, and financial greed—existed decades before Stoker’s book. Maybe X had read about these anti-Semitic Jewish stereotypes that Stoker’s Dracula embodies when he wrote his poem. Perhaps X had experienced anti-Semitism in his life; maybe this contributed to his wanting to study in Israel. Or perhaps, like me, X had simply fallen in love with Jerusalem—and liked writing about monsters—as I had; both of us Zionists fulfilling our right to live in Israel.

I guessed that X was an undergraduate because it seemed from his poem that he was discovering “the greats” for the first time. Had X been a graduate student, I think the poem might have indicated some already established awareness of the literary canon. He probably lived in the Resnick dorms on Churchill Boulevard, right across the street from the university. I lived in Idelson, on Lehi Street, the graduate dorm about a 15-minute walk from Resnick. I’m sure we both arrived in Jerusalem in the summer to take ulpan, the intensive Hebrew immersion course required for all foreign students. Our morning hours would have been the same, then, since ulpan ran from 8 a.m.-12 p.m. every day. He might have gone, like I did each morning, to the Forum—the meeting place in the center of the campus—before ulpan started, to meet up with others and drink coffee.

Despite my disappointment in X’s poem not being chosen, we had a pretty good final product. The June 1994 issue of Omphalos had 35 poems and one short story. The editorial staff’s favorite was Joy Bernstein’s “Miracles.” Her poem indicated that she was “waiting for God.” Perhaps the rest of the editorial staff was waiting for God, too, in Jerusalem. X wasn’t. He was wondering if Dracula was Jewish. I was still upset that we never even discussed X’s poem, which wasn’t, as the others had suggested, self-indulgent nonsense, at least not to me.

Soon after the issue came out, I began to pull away from the editorial committee. I started hanging out in cafés by myself in downtown West Jerusalem, journaling who I imagined X to be. I began reading Hemingway—For Whom the Bell Tolls—as X indicated he did. Like X, I was smoking too many cigarettes; I even took cigarette breaks at Omphalos meetings and went outside to smoke, hoping that perhaps X would walk by, and I would somehow recognize him. As the weeks went by, my obsession with X deepened. He had no idea, of course, that I was piecing together a narrative of his life based on the poem he wrote. Friends—the few I had—didn’t know about my obsession either. It was much easier to fixate on X than to develop real relationships.

I didn’t return to the magazine the next year. And though I continued to attend classes, I felt more detached from other Israeli students once I quit Omphalos. They were in their native country, whereas I was an American on a student visa. They served in the army and spoke perfect Hebrew. Most went home each weekend to their families in other cities across Israel. I remember one woman, Safa, though, with short black hair and thick arched eyebrows and swirly black eyeliner who sat next to me in our Shakespeare seminar. We had both been in the Toni Morrison and William Faulkner class the semester before, and she was nicer to me than the other Israeli women. When she’d arrive to class before me, she’d nonchalantly put her notebook in the seat next to her, saving the chair for me. When I noticed Arabic writing on the notebook as I sat down, I realized that Safa was Palestinian. I was embarrassed that I hadn’t known. “What difference would it have made?” she’d ask me later once we became friends. But before I thought about the significance of Safa’s identity, I mostly daydreamed about X.

X and I would have hung out all the time, I convinced myself. We would have sat in bars late at night in downtown West Jerusalem, like Champs, or Mike’s Place, or the Underground Bar, and talked about Hemingway for sure, and Bukowski, and Carver. I was sure he would have come home with me one night to my apartment on Palmach Street in the Katamon neighborhood. I’d have played him the cassette my friend Mark sent me from Chicago of Bukowski doing a reading while getting progressively drunker with each poem. At one point toward the end of the reading, the poet falls off his stool in the middle of reading “The Wine of Forever.” We would have smoked too many cigarettes, pontificating about the greats. Maybe we could have felt alone, together—a phenomenon I find more realistic in my adult relationships now—as we gazed in and out of our respective omphalos.

One afternoon, months after I had quit Omphalos, Safa asked me in class if I was OK. I had been skipping our Samuel Beckett seminar and she was worried. Though I didn’t tell her about my obsession with X, I did start spending more time with her. The first time was after class when she asked me if I wanted to have a coffee with her. “And a cigarette,” she laughed, as she methodically rolled her own as the steam from the coffee reached her tongue that licked the rolling paper. I learned about her family in Nazareth, a Palestinian city a couple hours north of Jerusalem. “I’m a Palestinian citizen of Israel,” she said. “My identity is different from Palestinians in the West Bank,” she explained, “since I have an Israeli passport and they don’t.” Safa lived in the same dorm as I did, but with other Palestinian citizens of Israel, whereas I lived with Israeli Jews.

One day when she invited me to her dorm room for tea, I noticed she was melting wax in a pot on the stove, next to the boiling tea. The wax was yellow and thick. She stirred it with a stick. She told me it was to “remove the dark hair from my arms,” and that all the women in her family did this. The wax smelled like vanilla or mint, or maybe it was the tea. I’m not sure now. She was embarrassed about how dark her hair was, she said, explaining she was much darker than Israeli women. I remember sitting that late afternoon in her room sipping tea, smoking her rolled cigarettes, the western sun coming in the small, square-shaped window where we blew out our cigarette smoke, watching her rip the hair off her arms with strips of wax. We’d become close, Safa and me. We had gravitated to each other naturally like awkward teenagers who don’t fit in at a school dance.

As a result of starting to feel more on the margins socially—and beginning to understand some of the ways Safa, a Palestinian woman, felt marginalized in Israeli society—I became more interested in Dracula’s “otherness,” too. In his book, Religion and its Monsters, Timothy Beal explores Dracula’s “monstrous otherness,” and argues that Dracula is both an outsider and an insider. His home is “the East within the West, the Orient within the Occident.” Dracula both fits in and doesn’t fit in. I saw how this was also true for Safa—my only real friend in Jerusalem—and I guessed that X would have, too. Above it all, edgy, countercultural—he’d be up all night thinking about the greats while the rest of the city was sleeping, and like a hipster Dracula he would sleep all day when others were working. He was beholden to no one—except, perhaps, his parents, who were probably paying the bills for his stay in Jerusalem.

As I got to know Safa better, she told me other stories of her family, who has lived in Nazareth since the 1840s. In 1948, Nazareth fell under Israeli Zionist rule, and has been occupied by Israel ever since. Aware of the significance of Nazareth’s Christian history, Israel “spared”—she made quotation marks with her fingers as she said the word—the city’s inhabitants the ethnic cleansing and expulsion that other Palestinian communities experienced. The city still suffers today, largely due to the Jewish Israeli settlement, Nazareth Illit, which has taken resources away from Nazareth and prevented the city from expanding. Safa told me that though her family was educated, they didn’t have the same access to education or jobs that Israelis do. Their neighborhood’s roads and resources are much lower quality than Israeli neighborhoods. She was the first one in her family, she told me, to attend Hebrew University. And she was really excited—I’d realize the irony later—to read Hemingway for the first time next semester.

As my friendship deepened with Safa, I began to think differently about Zionism. I was taught from an early age that the Jews came to settle the land and make the desert bloom. “A land for a people for a people without a land,” I learned at Zionist summer camp where, along with other mostly upper middle-class suburban Jews, we exhibited a kind of liberalism that never involved talking about Palestine. When I think about it now, I realize a significant flaw in the mythology I was taught. If the land was empty, as I was told, who were the Palestinians in the photos I’ve seen who “left” the land—ethnically cleansed and expelled, I would learn later—in 1948 with everything they could carry on their backs; where did they come from if the land was empty? And who were the Arabs who fought in 1948? I think I remember asking adults these questions as a child—I was starting to notice the holes in their logic—and being told by teachers at Hebrew school that the land was empty and, at the same time, that the land had been inhabited by Palestinians who, in 1948, willingly left on their own. Those who fought, my teachers told me, came from neighboring Arab countries, none of which wanted Israel to become a state.

This logistical impossibility doesn’t make sense, but myths don’t have to. Myths don’t rely on reason or logic. Cronus eats his children, one by one, except for Zeus, whom Rhea hides. When Cronus disgorges his children and the omphalos, the children come out all grown up. Myths don’t have to make sense. They perpetuate a narrative. The myth that Israel is a just society founded on righteousness and goodness pulls at the heartstrings of Zionists everywhere, while the reality of Israel as an occupying nation denying indigenous Palestinians the dignity to a self-determined existence remains hidden inside the myth for those who want to believe it. Safa’s story was different from the stories I was told. The land wasn’t vacant, awaiting the Jews to settle it. Every single Palestinian I have met since Safa has told me similar stories, and they have all been antithetical to the narrative with which I was raised.

Looking back now, I realize my questioning Zionism had further distanced me from the Omphalos editorial committee—though I wasn’t aware at the time—all of whom were ardent Zionists and spent their time with other Jews. I didn’t yet understand that before 1948, Palestinians had lived in all areas of Jerusalem, not just the East, and in Jaffa, and Tel-Aviv, and in all the cities and villages that dot the landscape. As I look back now, Safa was my first entry into a narrative different from the Zionist narrative I was taught. My anti-Zionism would come later, in stages, and would further separate me from loved ones as I, too, became marginalized for thinking differently.

Once I began spending time in East Jerusalem—on and around Salah Al-Din and St. George Streets—I learned more about the Palestinians who lived there. They were not the monsters I was told about. As my interest in the Palestinian narrative grew, I felt even more marginalized among Jews. None of the Jewish friends I used to have would ever have gone to East Jerusalem with me. A couple years later, after I’d given up on X, I’d try my luck with an actual human. I fell in love with an Armenian Christian, Tavit, who worked in his father’s shop in East Jerusalem. He showed me Ramallah, and Bethlehem, and Hebron, and bought me drinks in the same bars I’d imagined I might have gone with X in West Jerusalem. Like me, and like Safa, Tavit fit in and didn’t fit in. A member of the Armenian minority, he zigzagged seamlessly between East and West Jerusalem, using his Arabic or Hebrew or Armenian or English, depending on his location.

While Safa was a systemic representation of otherness, X remained my quiet obsessive made-up marginalized character. I wondered if the Dracula X portrayed in his poem could have lacked national pride, a “lack of an allegiance to a fatherland,” as Halberstam writes in her book. Perhaps X questioned his national loyalty to Israel like me, a Jew stuck in the melodramatic dark night of the diaspora. Mordecai, the Jewish character in George Eliot’s 1876 novel, Daniel Deronda, whom Robinson also discusses in her book, is an ardent Zionist devoted to creating a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Mordecai equates vampirism with a lack of patriotism. “The inhabitant of any country must pledge his loyalty, his energy, his blood, with the interests of his fellow citizens,” Mordecai insists. “Anything that detracts from these vows of kinship cannot help but turn an individual into a parasite of their country’s resources and goodwill—in other words, a vampire.” I wrote my undergraduate thesis on Daniel Deronda in 1992, a year before I’d move to Jerusalem, exploring the ways in which Eliot’s novel was a Zionist call for Jews like Mordecai—and me—to return to Palestine.

Once I was back in Chicago many years later, I read Edward Said’s “Zionism From the Standpoint of Its Victims,” and I learned that Eliot associates Zionism with civilized, Western thought and that Jews like Mordecai believed he would bring this Western civility to Palestine, in the East, which he considered savage and barbaric. Eliot believes, according to Said, that the bridge between the East and the West “will be Zionism.” After reading Said, I realized my thesis—all born of my love for Israel and literature and Zionism—was useless. I wondered if X would ever come to see Zionism from the standpoint of its victims like I was beginning to.

Before I left Jerusalem, though, I submitted a short story the following year to Omphalos. Despite having distanced myself so much from the magazine, the editors accepted my piece. The exaggerated cosmic self-importance—I wince reading it now—saturated this issue as well. My story, untitled, began, “In an attempt to preserve her immortal thoughts, she vigorously inscribed her words as the innocence slowly leaked from her soul.” Like the other pieces, mine was full of relationship drama peppered with biblical references. I hoped that X might have read my piece. Maybe he would have wondered who I was—though unlike him, my name was listed, so he could have found me quite easily.

By the time the Omphalos issue came out, Safa had moved back to Nazareth with her family for the summer. I fell in love with Tavit and eventually finished my master’s degree. Safa went on to get her Ph.D. in literature, and now chairs the English department at a small college near Nazareth.

I remained the only one who ever liked X’s poem, though I never learned anything about him. I never told anyone about him either, except my husband, who recently saw X’s poem sitting on my desk while I’ve been writing this essay, and asked me about the crumpled paper from 1993. In childlike terms, my creation of X showed me that I could be on the margins and still be OK. But it was a youthful folly, high up on a hill. And I am sure, after all that I conjured, X’s poem was likely more of a drunken scribble one night in a dorm than the myth I had created of him. At the time, it was much easier to obsess on men who wrote anonymous poems than to deal with the paradigm shifts occurring within me. I had discovered that the real monsters were the ones I had trusted who had told me about other monsters who weren’t monsters. But I was still in love with Jerusalem, and I didn’t know what to do with these feelings.

X had served a purpose for me in Jerusalem. I had projected onto him what others would come to see as monstrous and marginalized in me as I became anti-Zionist. I miss him, and Safa, even now, planning my curriculum lessons on Greek myths for high school students in Chicago. There was no Rhea to swaddle me in Jerusalem. Left to my own obsessions with monsters and Zionism, I fit inside of nowhere but the real and made-up stories of lovers and others. Who are any of us, after all, in our youth, to say we are not monstrous? Who do we think we are, really, to believe a myth and gaze into our omphalos day after day and to assert to anyone that someday we’ll wake up?

Liz Rose Shulman is a writer and teacher living in Chicago.