Anti-Semitism and Orthodoxy in the Age of Trump

How religious Judaism helps shield the American president’s disparagement of globalism, cosmopolitanism, and other features of progressive secular Jewry from claims of anti-Semitism

In response to the Pittsburgh massacre, in which Robert Gregory Bowers gunned down 11 Jews praying in the Tree of Life synagogue on Saturday, Oct. 27, 2018, all major Orthodox organizations condemned the attack in the clearest possible terms, but none was prepared to denounce the stated cause for the violence: white nationalism and the demonization of Jews as avatars for progressive and left-wing politics.

Why would the very group that was most noticeably targeted by white nationalism in the 20th century be the most reluctant to condemn it today? Some point to President Donald Trump and his allies’ support for Israel’s right-wing government, which itself has made common cause with some European anti-Semitic nationalist movements. Others such as the historian David Henkin claim that many of Trump’s Orthodox supporters “are the descendants (literally, in many cases) of Jews to whom the white nationalism of the post-1965 Republican Party was already resonating 30 or 40 years ago in debates about affirmative action, segregation, colonialism, and law enforcement.” Both theories, however, overlook Orthodoxy’s own position on anti-Semitism and the crucible in which it was formed.

Orthodoxy’s position on anti-Semitism was first theorized in the interwar period when Central and Eastern European rabbis and laypeople founded the first Orthodox political party, Agudath Israel. Like all political parties operating on the continent at the time, the Orthodox quickly found themselves choosing between the rock of Stalin on the left, and the hard place of Hitler on the right. Whereas Stalin posed a threat to Jews’ religious institutions and observances, Hitler’s target was Jews themselves and their involvement in German political and economic life.

The Orthodox, however, operated under the illusion that Hitler’s wrath was directed only at certain kinds of Jews and that their own prohibitions against intermarriage and commitments to cultural difference could persuade the German chancellor that they were to be trusted allies. Stalin would destroy Orthodoxy, but Hitler, they figured, would only be bothered by those Jews who were Communists or Marxists. Many in the Orthodox community surmised that Jews who held fast to their spiritual heritage would pose no threat to Nazi Germany and it was therefore Stalin who was to be feared.

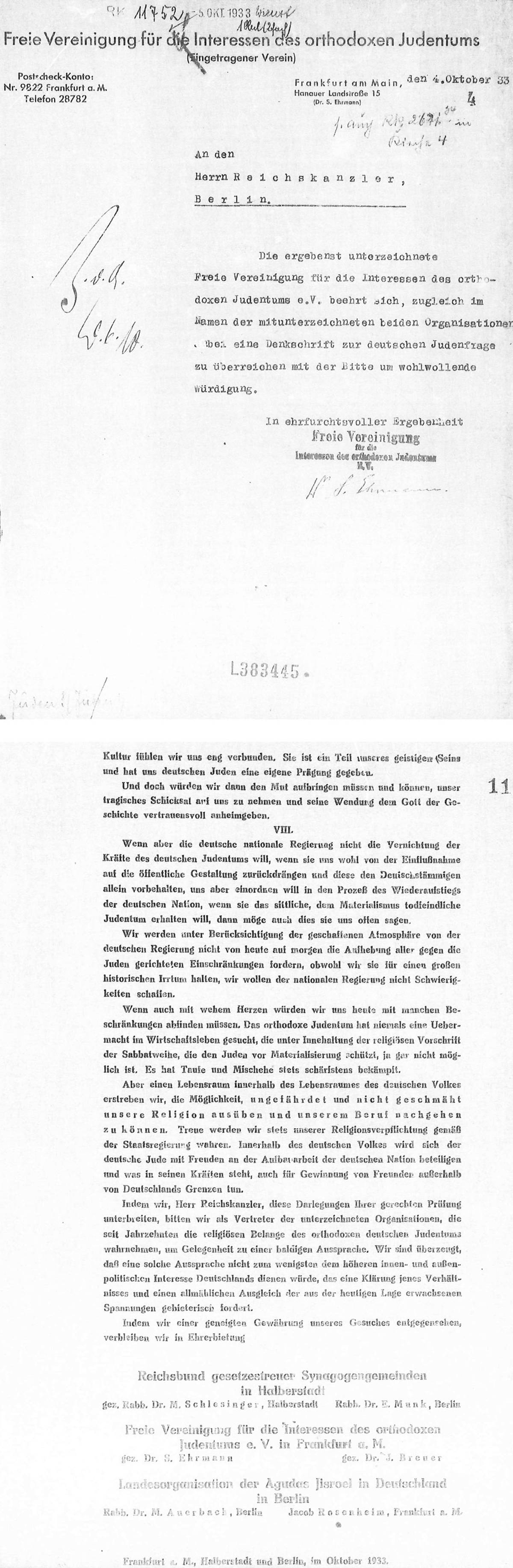

As Marc Shapiro has shown, German Orthodox leaders directly appealed to the German chancellor (Hitler), arguing in 1933 that “Marxist materialism and Communist atheism share not the least in common with the spirit of the positive Jewish religious tradition, as handed down through Orthodox teachings obligatory on the Jewish People. … We have,” they recalled, “been at war against this religious attitude.” Orthodox leaders sought to find common ground with Hitler by demonstrating their own virulent hatred for left-wing and progressive Jews. They proclaimed: “We have always combated the corrosive spirit of materialism with religious idealism.”

In their attempt to curry favor with Hitler, Orthodox leaders not only stressed their own loyalty to the German people, but went out of their way to stress the structural similarities between Hitler’s position. “We seek a Lebensraum within the Lebensraum of the German people,” they maintained.

The German rabbis’ position was reaffirmed by the leaders of the Polish branch of the Agudath Israel party who aligned themselves with Pilsudski’s nationalist union. As historian Gershon Bacon notes in his study on early 20th-century Orthodox politics, “the Agudah-Sanacja alliance stemmed from perceived common values and ideologies.”

Both parties held authoritarian, conservative, and pro-business platforms and favored strong charismatic and authoritarian leaders who appealed to religious symbols and traditional practices. From the outset, Agudath Israel challenged a central axiom of modern Jewish politics, Bacon explains, “namely that progressive forces on the Polish left were natural allies of the Jews.”

Agudath Israel’s leaders assumed that Stalin’s hatred of religion eclipsed Hitler’s hatred of foreign groups. For whereas the latter put their “bodies at risk, the former threatened their soul, a far greater threat than that of physical death,” explained Rabbi Elchonon Wasserman the dean of the Baranovitch Yeshiva in Lithuania. Wasserman, who was murdered in the Holocaust, was known as one of the leading authorities of Orthodoxy in his generation. Until today, he and his teacher Israel Meir Kagan (the Chofetz Chaim) are revered as Gedolim, “the great ones,” by Orthodox Jews across the world.

***

On the surface, Agudath Israel’s political calculus followed that of Catholic political parties. Already in 1891 Pope Leo VIII issued Rerum Novarum, an encyclical that denounced the spread of “Marxist-atheism” across Europe. The church’s position was sharpened with the rise of Stalin, the Soviet appropriation of church property, and the dissolution of the episcopal hierarchy on Russian lands. The church saw communism as an evil that stood outside its ranks, one that threatened Christ’s dominion over the world.

Pope Pius XI’s encyclical Divini Redemptorius, published in March 1937, provided an in-depth theological argument against a materialist theory of the universe and argued that “the evil we must combat is at its origin primarily an evil of the spiritual order. From this polluted source the monstrous emanations of the communistic system flow with satanic logic.”

Where Orthodoxy’s position was unique, however, is the way in which it identified left-wing politics as a cancer from within the Jewish collective, something internal to Judaism itself. The fight against Marxism and a materialist theory of the world was not only to be waged against gentiles, but first and foremost against other Jews who played integral roles in founding these new movements.

Wasserman identified Judaism’s primary present-day enemies as Jews who held leadership positions in the left; those he considered to be descendants of both the biblical “mixed multitude” as well as the tribe of Amalek. The “mixed multitude” referred to those Egyptians that followed Israelites when they left Egypt only to cajole them into worshiping the Golden Calf in the desert. Amalek was the first group to attack the Israelites in the desert; its descendants were deserving of death by biblical mandate. Wasserman employed the category of Amalek to describe leaders of the Yevsektsiya, the Jewish section of the Communist Party, as well as Zionists residing in Palestine (most of whom were then aligned with the left) and around the world. He advised his flock “to physically fight against them with arms. To prepare oneself to kill.”

There was ample reason for Wasserman to consider Stalin and his Jewish minions in the Yevsektsiya as the primary threat. The Soviet leader had systematically worked to destroy Jewish institutions, synagogues, and schools. The Yevsektsiya equated Judaism with bourgeois values and brought a religious zeal to shutting down Jewish cultural and religious institutions. They were Stalin’s undertakers preparing Eastern European Jewry for its final burial.

Wasserman’s hatred of Stalin, however, also stemmed from his opposition to the new forms of Jewish identity put into circulation by both anti-Semites as well as what might be called Jewish materialists. For late 19th and early 21st century Eastern European Jews, being Jewish was increasingly becoming less a private religious matter based on beliefs, rituals, or abstract metaphysical ideals and more defined in material terms; Jewishness was based on the social, economic, and linguistic features of a body of people called Jews. The very same scientific and economic theories that popularized the term anti-Semitism were also were used to construct a new type of identity that positively valued Jews’ relationship to the material world.

Whereas the anti-Semite described the Jew as an egoist who hoarded goods and resources, the Jewish materialist claimed that Judaism promoted the fair and equal distribution of resources in society. Whereas the anti-Semite claimed that the Jew was a lesser race, the Jewish materialists argued that Jews were a distinct ethnic group. Whereas the anti-Semite claimed that Jews’ demand for national liberation or conversely commitment to cosmopolitan values reflected a form of dual loyalty or sedition; the Jewish materialist claimed that it reflected a hope to be treated like all historical nations or a world without want or need.

The Jew as a social and economic actor defined by biology, race, or history, separate and distinct from adherence to the Torah or observance of Jewish law was, for the Orthodox, a contradiction in terms.

In its most radical form, the material Jewish identity was associated with universalists, those Isaac Deutscher famously identified as “non-Jewish Jews,” men and women such as Trotsky, Marx, and Luxemburg who lived “on the margins or in the nooks and crannies of their respective nations. They were each in society and yet not of it.” However, it was largely embodied in those that identified with the Jewish labor movement, the Bund, as well as Zionists who saw themselves as disciples of Marx and were aligned with Russian revolutionary political movements.

In opposition to “non-Jewish Jews,” Zionists, and Bundists, the Orthodox repeatedly asserted the primacy of spiritual concerns over Jews’ material well-being; always focusing on the spiritual battle over the physical one. “Though the programs of the Jewish parties are directed at material matters,” Wasserman claimed, “the implications of their programs are spiritual and lead to heresy and freedom. Accordingly, our program,” he continued, “is the inverse … it is directed at spiritual matters to spread the knowledge of Torah and fear of God. Those looking to rejoice in victory are those who are careful to avoid taking initiative regarding material matters. … As for material matters, they are in God’s hands alone, and spiritual matters are in the hands of man.”

Put in Marxian terms; Wasserman was not interested in the fate of “the marketplace Jew” but rather in the “Sabbath observing Jew.” In fact, Wasserman maintained that the whole liberal program of creating a Jew who could freely circulate in the marketplace as a productive citizen was a heretical proposition.

From the perspective of Western history, the Orthodox were focused on combating anti-Judaism, fighting against those who attacked their God, their beliefs, and religious institutions. Fighting anti-Semitism—the material discrimination of all Jewish bodies irrespective of belief and practice—indicated a lack of faith in the divine plan of history and a categorical misunderstanding of who in fact was a Jew.

For in many instances the targets of anti-Semitism, at least according to Wasserman, were anything but Jews. The very charge of anti-Semitism—the discrimination of Jews simply because they were marked as such by material, biological, or historical categories—reflected a type of Jewish identity that the Orthodox never fully endorsed. The Jew as a social and economic actor defined by biology, race, or history, separate and distinct from adherence to the Torah or observance of Jewish law was, for the Orthodox, a contradiction in terms. As Wasserman’s teacher Israel Meir Kagan explained, “there is no such a thing as a secular Jew, if someone is secular then they are not Jewish.”

When Wasserman licensed the killing of left-wing Jews in Russia, Palestine, and around the world in the 1920s and ’30s, he begrudgingly admitted that he was in no position to carry out such an order. “We do not have army generals,” he conceded. In reality, Wasserman spent most of his adult life pleading for monies on behalf of his impoverished students. He instructed his followers to remain put in Europe, study the Talmud, and endure their suffering.

Wasserman, like many of his Orthodox brethren, would refuse the entreaties made by groups to immigrate to the United States, seeing them as contaminated by their ties to the left. True to his word, he would die with his students at the hands of the Nazis when they invaded Lithuania in 1941, having returned there from America.

***

Orthodoxy’s vigilance in combating anti-Judaism mirrors the Janus-faced relationship of the American Christian right’s stance toward Jews. It is precisely their staunch support for certain kinds of Jews and certain forms of Judaism that makes possible their attacks against, or at the very least disregard for, defending the rights of other types of Jews. Their assaults against globalists, progressives, and boundary-crossers are not, they claim, directed at Jews, because real Jews also oppose globalists, progressives, and subversives. If progressive Jews are not really Jews and if left-wing Jewish values are not really authentically Jewish, then it follows that opposing these types and values does not indicate any particular anti-Jewish animus.

Whereas European leaders ignored Orthodoxy’s distinction between authentic Jews and left-wing heretics, it has found receptive audiences on this side of the Atlantic. While Trump uses the term anti-Semitism when referring to protecting Jews against acts of violence, his focus is less on a distinct biological or historical group that identifies as such and more on specific Jews and a specific kind of Judaism. He can thus simultaneously denounce opponents such as George Soros as cosmopolitans secretly waging war against Western values and at the same time support Jewish private schools in the United States and the relocation of the American Embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.

To be sure it’s doubtful that Trump has given much thought to this distinction but his strong support for Israel, the spiritual and religious center of Judaism, suggests as much.

The seeming contradiction between an American president who never misses an opportunity to boast about a largely symbolic embassy move and conversely misses every opportunity to denounce white nationalism, is actually no contradiction at all. It comes as little surprise that the two American pastors that Trump delegated to bless the opening of the Jerusalem embassy respectively claimed that Hitler was a messenger sent by God and that Jews who do not embrace Christ are damned. When pressed on the issue, one of them, Pastor Robert Jeffress responded, “I have never said anything derogatory about the Jewish people. I talked about today the oneness we share in worshiping the same God in the Scriptures.” In other interviews he further explained, “Jerusalem has been the object of the affection of both Jews and Christians down through history and the touchstone of prophecy.”

Jeffress’ focus on Judaism and disinterest in the global socio-economic well-being of Jews is borne out from recent polling data gauging American evangelical attitudes toward Jews and Israel. A 2017 LifeWay Research Poll reveals that upwards of 80 percent of American evangelical Christians believe that events surrounding the establishment of the State of Israel were the fulfillment of Bible prophecies that show we are getting closer to the return of Jesus Christ. On the other hand, only 20 percent of those polled understood these events in strictly geopolitical terms.

Yet evangelical support for Israel should not be reduced to simply cynical expressions of Protestant philo-Semitism that ends in Jews moving to Israel and eventually all converting to Christianity. It is bound up in the history of religious freedom in the United States and follows 50 years of concerted efforts on the part of American Protestantism to address its own history of anti-Semitism. For many in its ranks, contemporary Protestant outreach to Jews reflects an act of contrition for the movement’s association in the 1930s with pro-Fascist splinter groups led by the likes of anti-Semites Reverend Gerald L.K. Smith and the evangelical preacher Gerald Winrod. For their part, American evangelicals have allocated large-scale resources to those Jewish concerns that are of central importance to Christians.

Still, the Christian right, Orthodox Jews, and the Trump administration have all found common cause in promoting a definition of anti-Semitism that undermines its historically most commonly assumed meaning. For them, the Jew is something religious and spiritual and is divorced from his or her material existence. The decoupling of Jewish identity from the common material images associated with anti-Semitism allows the president to employ what others still identify as anti-Semitic material tropes at new targets. The president’s disassociation of anti-Semitic signifiers (globalists, border-crossers, immigrants, cosmopolitans, atheists) from Jews affords him the ability to deploy these charges indiscriminately, without bearing the responsibility for the forms of discrimination historically attached to these terms. Divorced from their anti-Semitic histories, those terms are now free to target not only Jews but others as well, such as Syrian refugees or Mexicans.

If Jewish identity has nothing to do with left-wing and progressive politics, with a cosmopolitan spirit, or a globalist orientation, then it follows that those who employ such terms to demonize their opponents are not in fact anti-Semites. To criticize Wasserman and the Orthodox for their lack of foresight is callous, but not to recognize their flawed and violent logic would be derelict.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Eliyahu Stern is Associate Professor of Modern Jewish Intellectual and Cultural History at Yale University. He is the author of Jewish Materialism: The Intellectual Revolution of the 1870s.