Are Books All We Have Left?

A masterful encyclopedia sums up our history and culture but raises the question of where Jewishness lies today

The genealogical lists that fill the Bible are notoriously hard going; but if you want to reflect on the strangeness and singularity of Jewish history, a good place to start is the list of generations in Genesis 11. Here are the fathers and sons who bridge the centuries between Noah and Abraham—men with names like Arpachshad, Peleg, and Serug, which are strange to the eye and on the tongue. When the name of Abram first appears in the Bible, it is in this list of names, and for an instant the context manages to defamiliarize it. We peer into an alternate reality where the syllables of Abram sound as foreign, as primordial, as Arpachshad—a world where Abram is not yet Abraham, not yet the father of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

In these names, we can read in very concrete terms what it meant for the Jews to be a chosen people. There is only one reason why Abraham escaped the anonymity that encloses his ancestors and contemporaries. It is that, as we read in Genesis 12, God made him a gratuitous promise: “I will make of you a great nation and I will bless you.” In token of this covenant, God changed Abram’s name to Abraham just as, two generations later, he would change Jacob’s name to Israel, “for you have striven with God.” For centuries afterward, Jacob’s progeny would refer to themselves as b’nei Yisrael and am Yisrael, thus inscribing the name of God in their own name.

It is paradoxical, then, that in their new book, Jews and Words, the Israeli novelist Amos Oz and his historian daughter Fania Oz-Salzberger see in the name B’nei Yisrael the promise of a liberation from religion. Starting in the 19th century, they argue, Jews began to conceptualize Judaism as a religion, in parallel with Christianity and Islam. But historically speaking, the word and idea of “Judaism”—in Hebrew, yahadut—have shallow roots among the Jewish people. (In the Hebrew Encyclopedia, they point out, the word “Jew” has no entry: Look it up and you will be redirected to “The People of Israel.”)

To the Ozes, the word yahadut is an ahistorical coinage, now favored by the Orthodox of Israel as a “tool for correcting the infidels.” But if you replace “the Jews” and “Judaism” with the older term “children of Israel,” they argue, you can find your way to a more capacious and potentially more secular way of thinking about what it means to belong to the Jewish people. The Children of Israel are not all those who believe in a certain creed or practice a certain set of laws; they are all those who descend (biologically or, the Ozes would insist, by culture and tradition) from the patriarchs. To be a Jew is not to practice a faith, but to belong to a nation; and you can’t forfeit membership in the nation by losing the faith.

This linguistic argument recapitulates the basic thrust of Zionism, which was largely a secularizing movement. The Zionist project was to reconceive Jewish nationhood in secular political terms; the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine was, in a way, only the symbol or capstone of this more fundamental ideological work. Yet there was always a deep paradox in this mission, which surfaces, once again, in the question of names. The inevitable name for the Jewish state, of which Amos Oz has become one of the greatest novelists, is Israel: From b’nei Yisrael and am Yisrael come medinat Yisrael. Yet the name Israel bears within it the memory of Jacob’s wrestling with the angel, and of the divine covenant. Israel could not have become Israel without God. The question that faces millions of Jews today, and that the Ozes are canvassing in their passionate book, is whether Israel can remain Israel once God has disappeared.

The title of Jews and Words suggests the answer that Oz and Oz-Salzberger have to give. “What kept the Jews going,” they write, “were the books.” From earliest times, the Torah was at the heart of Jewish identity. But with the destruction of the Temple and the kingdom of Judea, in the first century CE, words and books became the very substance of Jewish practice and belief. You could no longer offer a sacrifice in Jerusalem, but you could study the Mishnah at the beit midrash—and after the Mishnah the Talmud, and Maimonides, and the Kabbalah, and so on down the centuries. For the Ozes, initiation into Jewishness meant instruction, most often carried out from father to son, in how to read texts. “The children were made to inherit not only a faith, not only a collective fate, not only the irreversible mark of circumcision, but also the formative stamp of a library.”

Today, most Jewish children are still circumcised—though it’s possible we’re about to undergo a sea change in public attitudes toward circumcision that will make it a much more difficult choice for Jewish parents. But not all Jews inherit the same faith—they are Orthodox, Conservative, Reform, secular, atheist, indifferent. And not all of us inherit the same fate; on the contrary, the fate of Jews in America, the pressures and possibilities we face, are very different from those facing Jews in Israel. Every day it is becoming easier to imagine how those differences may one day result in a serious breach between the world’s two major Jewish communities.

What that leaves is the library. Not the contents of the library, of course—Jews today grow up with a very different reading list than our ancestors had 300 or 2,000 years ago. What the Ozes are banking on is that the very idea of libraries, of reading and writing, of textuality, are enough to sustain a coherent Jewish identity. Much of Jews and Words is devoted to an affectionate exploration of Jewish feelings toward books, writing, and the intellect in general. In the Seder’s Four Sons and the dialectic of the Talmud, the Ozes see a Jewish respect for questioning and debate. In the anxiety Jewish parents famously feel for their children, they find the key to cultural transmission: “Jewish parenting had, perhaps still has, a unique academic edge. Being a parent meant performing some level of text-based teaching.” In the bar mitzvah boy’s speech, they find the Jewish pressure to contribute something new to tradition. All these qualities persist, they argue, in modern, secular Israel, helping to explain the country’s high-tech prowess: “We are talking habits, not chromosomes.”

But it doesn’t take long for the reader of Jews and Words to realize that, if the Ozes feel confident betting on literacy to sustain Jewish continuity, it is only because they have made a large covering bet, one that they don’t fully acknowledge: a bet on Hebrew—which is also to say, on the state of Israel. The words that the Jews have had in common have always been Hebrew words—in the Torah, the Talmud, the law codes and commentaries. Whether she wants to be or not, an atheist living in Tel Aviv is the heir to all these words: She can choose to read them, and even if she doesn’t, the language and literature that surround her draw on them. Jews can be Jews on the strength of words only if those words are Jewish words, and only Hebrew is an exclusively, unquestionably Jewish tongue. “We strongly believe,” the Ozes write, “that you cannot do ‘Judaism’ without gazing deeply into the eyes of Hebrew language and civilization.”

Thanks to Eliezer ben Yehuda and all the other early Zionists who resurrected Hebrew as a language of daily life, Israelis are born with an ineradicable link to the Jewish past. Oz and Oz-Salzberger are confident that this link, combined with Jewish habits of mind and education, is enough to sustain Jewish identity. What they are really arguing, then, is that it is possible to be an atheist Israeli and still be in a meaningful sense a Jew, a member of am Yisrael. This has natural implications for Israeli politics, which the Ozes are quick to voice: They resist the imposition of religion on the secular state, and they have no interest in the West Bank just because it used to be called Judea and Samaria. On both counts, they are heirs to a long Zionist tradition. Indeed, much of what is noblest and best about Zionism can be heard in the pages of Jews and Words.

But where does this leave American Jews? Our words are not, usually, Hebrew words; they are English, part of a global language with Anglo-Saxon and Christian origins. Can we, too, trust to language and intellect to make us genuine Jews, even if we neglect Hebrew and do not keep up Jewish observance and even disbelieve in God? Jews and Words itself is an ambiguous answer to this question. It is a brief for Hebrew written in English, a book by Israelis addressed to Americans. Does this mean that Oz and Oz-Salzberger recognize the validity of English as a Jewish language, or does it, on the contrary, mean that they are sending us a message in a bottle, asking us to come home? “As long as we still have our common words, we are a community,” they write hopefully near the end of the book. But do all Jews have words in common?

That is the question that seems to motivate the great new publishing project of which Jews and Words is a herald: the Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, a monumental series published by Yale University Press with support from the Posen Foundation. The Ozes’ book is published in conjunction with the first installment of this 10-volume series, which when complete will offer an anthology or source book for all of Jewish history, starting with the biblical period and ending in the 21st century. And in keeping with the focus of the Posen Foundation, and its founder Felix Posen, the series defines Jewishness broadly, with an emphasis on secular cultural achievement. Here, if anywhere, is the “formative … library” the Ozes rely on to preserve Jewishness, designed specifically for the use of American Jews, and it immediately becomes a necessary item for any serious Jewish or general-interest library to own.

The Posen Library, under the general editorship of James Young, has launched with the publication of its chronologically last volume, Volume 10, which covers the years 1973-2005. Even a quick glance through the book, which has the dimensions of an encyclopedia, is enough to show how much labor—of editing, translation, acquiring permissions—went into making it, under the direction of the volume’s editors, Deborah Dash Moore and Nurith Gertz. Here are 250 pages of fiction (mostly in the form of brief excerpts from novels and stories), and 50 pages of poetry, and 100 pages of memoirs; here are bits of plays, YA novels, essays, new liturgical works, and recipes. If you can think of a Jewish writer, he or she is almost certainly here.

There is even room in the Posen for panels from graphic novels, in the section “Popular Culture,” and reproductions of paintings and sculptures, under the rubric “Visual Culture.” At the end of the book are lists of Jewish works in other media, which cannot be captured on the page, but which form part of the Posen’s imaginary canon: films, dances, classical and popular music. Within each section, items are sorted chronologically by year, even when this means splitting a contributor’s work: Thus we meet Philip Roth in 1986, with a section of The Counterlife, and again a hundred pages later in 1997, with a chunk of American Pastoral.

The first question any reader, or editor, would ask when confronted with a “library of Jewish culture and civilization” is what counts as a Jewish work. For earlier volumes of the series, that question won’t be so difficult: Presumably there will be a lot of scripture, Talmud, liturgy, and responsa in volumes still to come. For a book that covers the last three or four decades, a time when Jewish culture is more international and more fragmented than ever before, it is a more pointed challenge. One way the Posen Library answers it is through sheer size. There is room between these covers for just about everything that anyone might consider Jewish. That includes texts that deal directly and explicitly with Jewish issues—everything from Judy Blume’s Starring Sally J. Freedman As Herself, which has traumatized generations of young readers (including me) with its Hitler-fantasies, to historian Anita Shapira’s essay on Zionist models of Jewishness, to poet Marcia Falk’s pantheistic rewriting of the Shema: “Hear, O Israel—The divine abounds everywhere and dwells in everything; the many are One.”

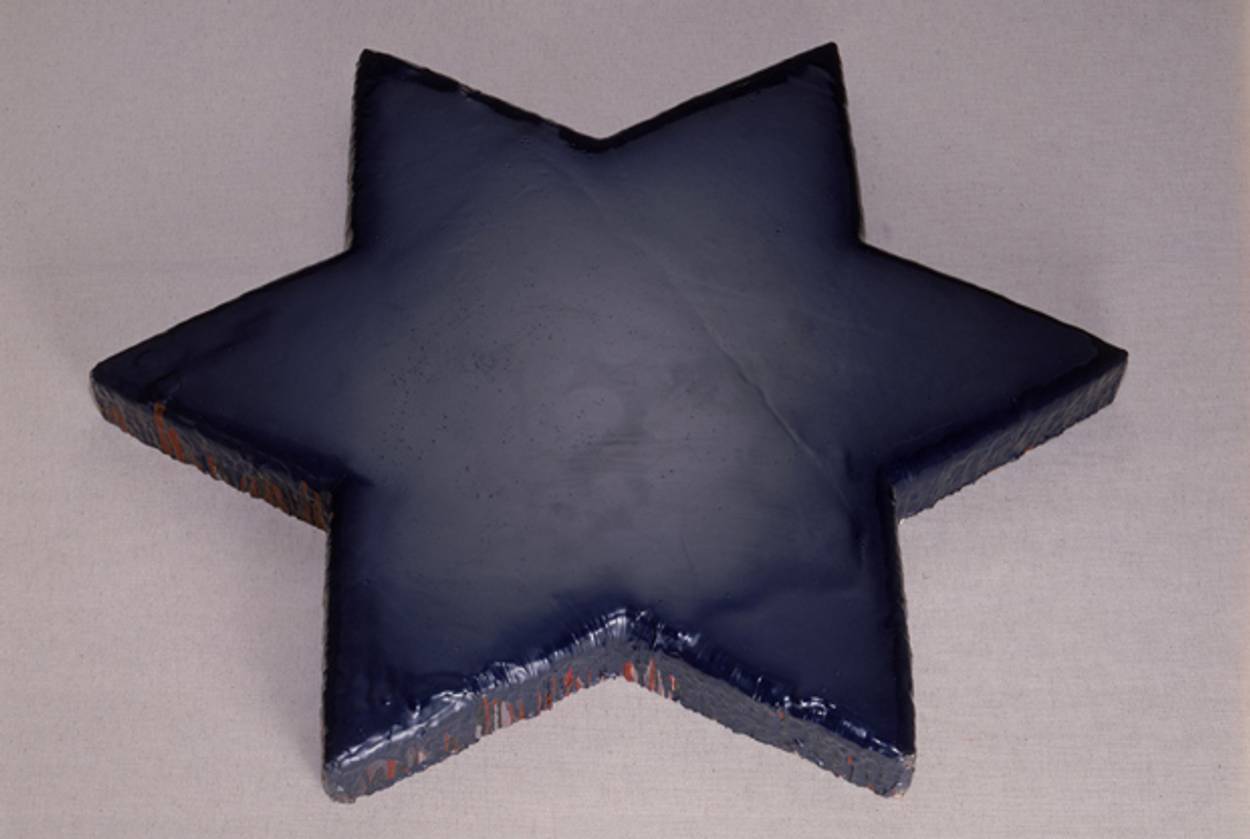

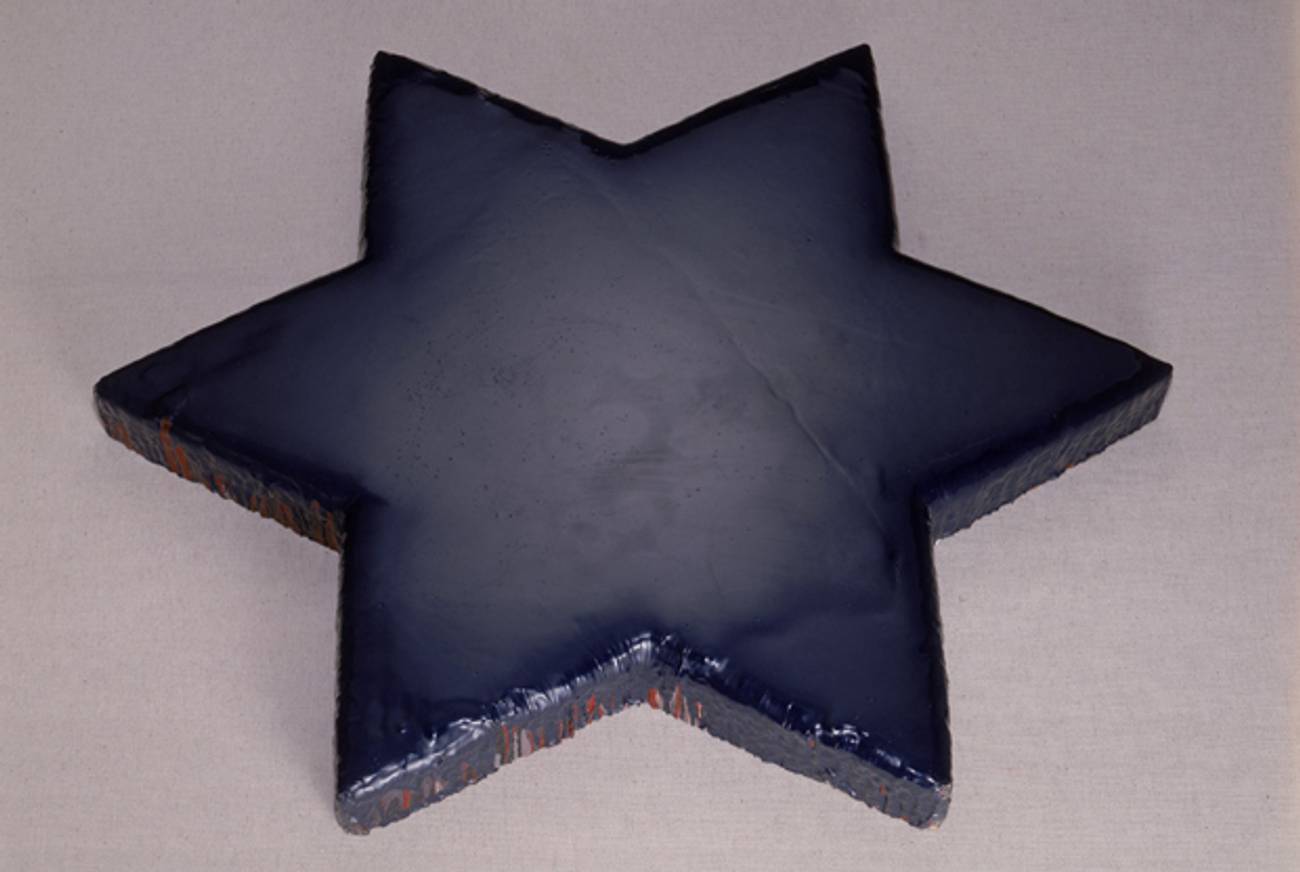

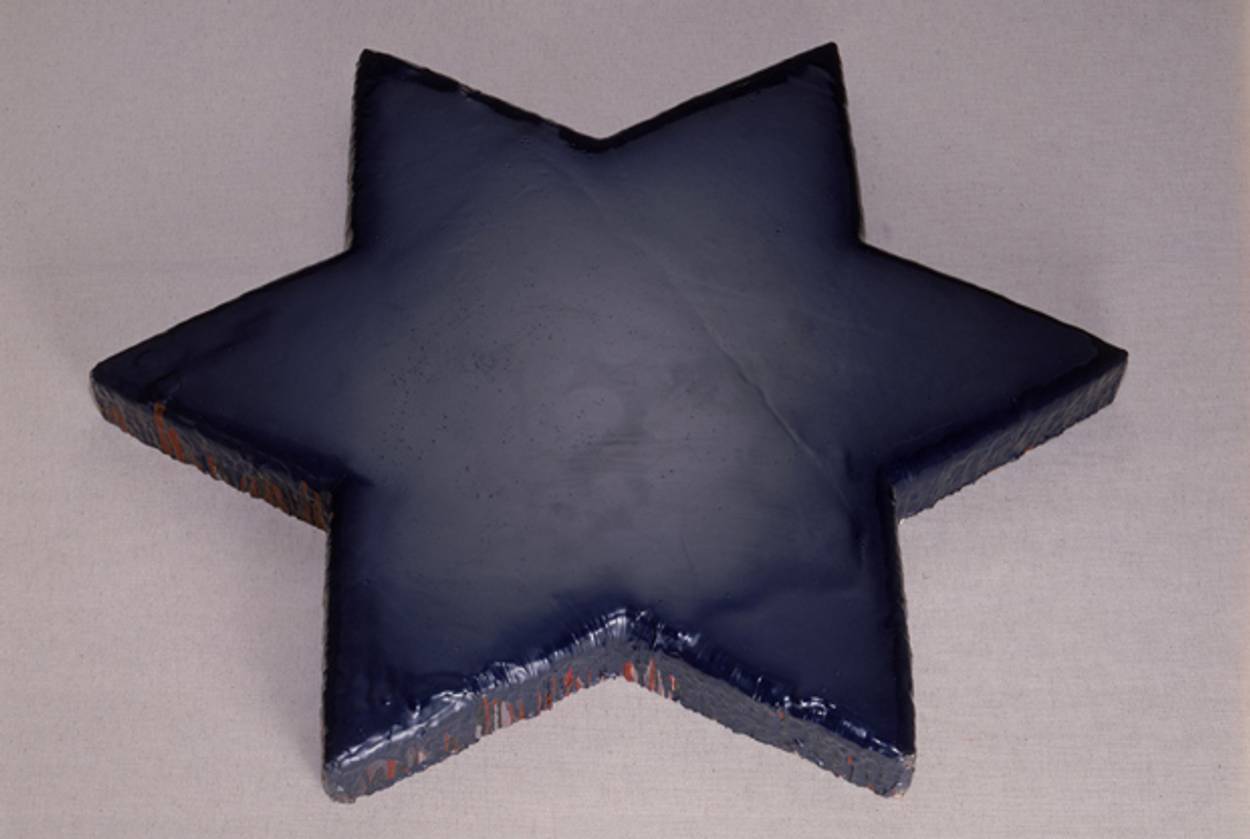

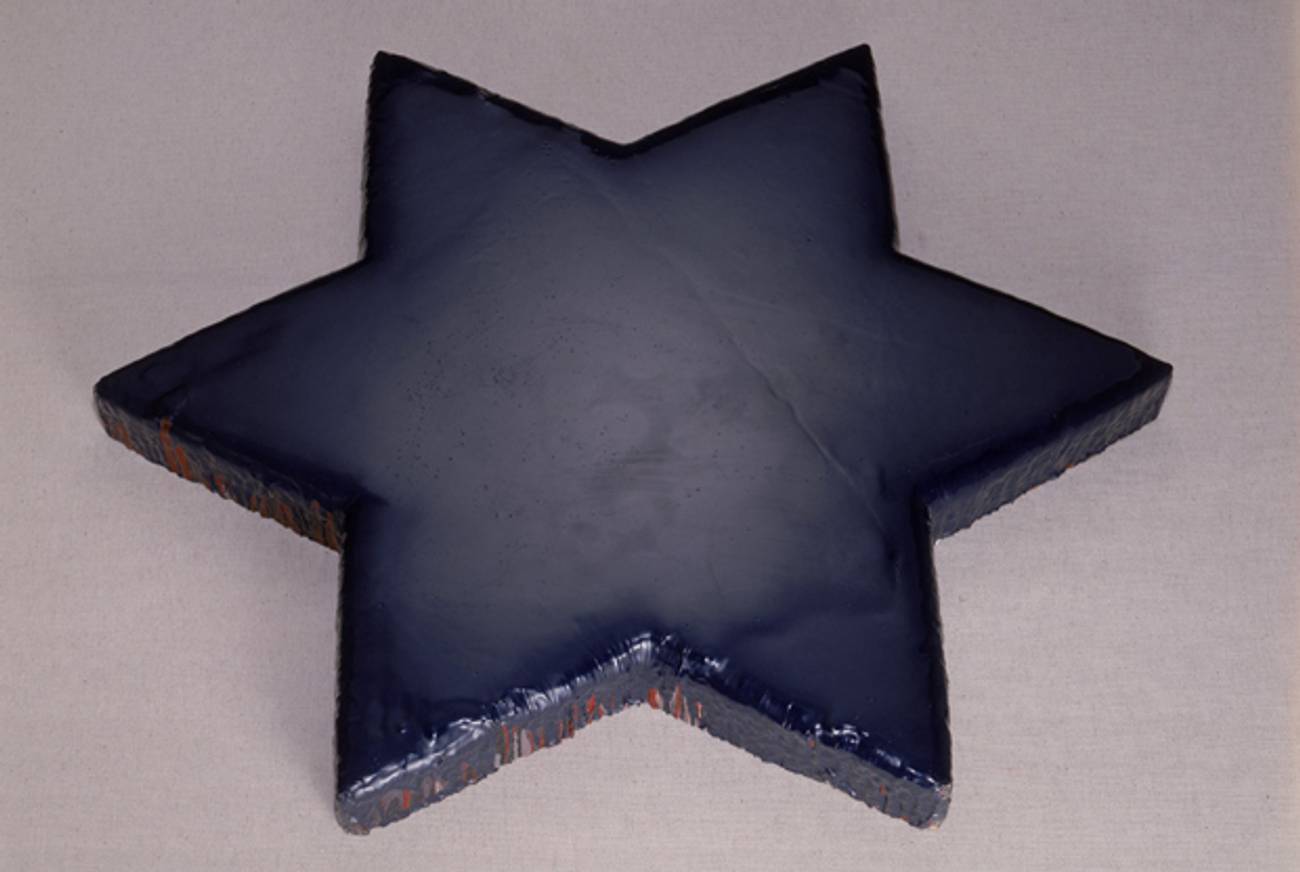

But it also includes many items whose Jewishness could not necessarily be discerned without knowing that their creators were Jewish. This is especially true in the “Visual Culture” section, where images that “read” immediately as Jewish—a blue star of David, by Michael David, labeled “A Jew in Germany,” or Joel Otterson’s “Unorthodox Menorah”—consort with others that have nothing evidently Jewish about them—such as Laurie Simmons’ uncanny doll-diorama “Café of the Inner Mind,” or Barbara Kruger’s famous poster, “your body is a battleground.”

The very first item in Volume 10 already begins to pose the problem of what counts as a Jewish text—a page-long excerpt from Saul Bellow’s novel Humboldt’s Gift. Bellow is the greatest American Jewish novelist, and it would not be hard to find passages from his work that deal explicitly with Jewishness; perhaps Volume 9 will feature excerpts from The Victim or Herzog. But the selection the editors make, from near the beginning of Humboldt’s Gift, does not contain any Jewish references. What it does feature is the narrator Charlie Citrine’s strong sense of attachment to the dead: “Out in Chicago Humboldt became one of my significant dead. I spent far too much time mooning about and communing with the dead.”

Is that, perhaps, what makes this a Jewish text—the sense that Jews, especially after the Holocaust, are defined by their tender obsession with the dead, with the past? But then, isn’t piety toward the dead part of every human culture? In this way, the Posen Library compels the reader to start asking what parts of his experience are informed or inflected by Jewishness. If it is not Jewish to mourn, is it at least possible to mourn Jewishly? If it is not Jewish to make images, is it Jewish to make images of dolls, as Simmons does—dolls that both violate and paradoxically obey the biblical injunction against making graven images?

Once again, as in Jews and Words, the Posen Library’s answers to these questions seem to divide along the imaginary border that separates, and joins, Israel and America. There are really two narratives being told in Volume 10, starting with the decision to begin the volume with 1973. That year, as the editors note in their introduction, marks a crucial moment in the history of the State of Israel—the Yom Kippur War, which heralded a number of social and political transformations. It also marks a crucial moment in American history, with the Watergate scandal and the end of the Vietnam War. But does it have any particular significance in American Jewish history? Is it even possible to write an American Jewish history on its own terms, with its own periodization and pivotal dates? Or do all Jews necessarily live by a historical calendar determined in Israel—just as, in Jews and Words, the continuity of Jewish life is assured by the language spoken in Israel?

Certainly, it is the American Jewish texts and works in the Posen Library that ignite the most anxiety about their Jewishness. When an Israeli poet like Erez Biton writes a love poem, there does not need to be anything thematically Jewish about it for it to count as part of Jewish literature, simply because it is written in Israel and in Hebrew:

How about what you’re doing right now, Yael?

To know something about her bed, about your bed, Yael,

To know her soft thoughts in the morning instant …

Whereas when an American Jewish poet writes a similarly universal poem, the question immediately arises: Is this a Jewish poem, or an American one, or simply the expression of a basic human experience, like Ira Sadoff’s “My Father Leaving”;

When I came back, he was gone.

My mother was in the bathroom

crying, my sister in her crib

restless but asleep. The sun

was shining in the bay window,

the grass had just been cut.

No one mentioned the other woman,

nights he spent in that stranger’s house.

It is not until the end of the poem, when Sadoff writes, “But I was thirteen/ and wishing I were a man,” that we find even an echo of a Jewish reference, in this case to the bar mitzvah ceremony. It is as though Sadoff himself wanted to mark the poem, however lightly, as a Jewish poem, to ensure its double citizenship in the canons of American and Jewish literature.

What the Posen Library represents, then—at least when it deals with the near-present—is a canon defined by anxiety about whether it constitutes a canon. A certain anxiety is, perhaps, implicit in the very idea of a “Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization.” The sheer completism of the project, the desire to get everything from recipes to choreography to novels to prayers between two covers, makes the reader think of the Posen Library in apocalyptic terms, as a kind of Noah’s Ark of Jewishness. Indeed, the making of anthologies is often the sign of a civilization in crisis: Think of a figure like the seventh-century Christian bishop Isidore of Seville, whose major work (aside from his bitter polemics against Judaism) was the Etymologiae, a 20-volume compendium of everything the Roman world knew about history, which served as a time capsule against encroaching barbarism.

Or, to use a more appropriate example, think of the Mishnah—a traditionally oral body of law that was written down around 200 CE in order to preserve it through an era of Jewish dispersion and decline. It is possible to see the Posen Library as a kind of secular Mishnah, an attempt to capture the core of Jewishness in a huge but finite number of pages. The difference is that while the rabbis knew what constituted that core—it was the Oral Law, the accumulated practice of centuries—the editors of the Posen Library cannot be so sure.

On the contrary, if there is one thing they are sure about, it is that contemporary Jewishness does not reside where it has always lived before, in religious law and practice. Only a small fraction of Volume 10 is made up of texts on religious subjects; the section on “Spiritual and Religious Culture” occupies just the last 100 of the book’s 1,100 pages. Here and elsewhere in the volume there are fascinating items on how Judaism itself is practiced today; one of the most illuminating things I’ve read on contemporary Orthodoxy is Haym Soloveitchik’s essay “Rapture and Reconstruction,” in which he describes the decline of traditional practice and the rise of text-based knowledge among the Orthodox. (There are also some fairly dreary, but historically significant, denominational mission statements.)

Contemporary Jewishness does not reside where it has always lived before, in religious law and practice.

It will be interesting to see how, and whether, this emphasis on secular Jewish culture is maintained in the earlier volumes of the Posen Library. When it comes to the period 1973–2005, the emphasis is quite understandable, even if only in demographic terms. Today, more Jews define themselves as Jews through “culture and civilization” than through Orthodox practice. Yet a culture, like a song, is made up of words and a tune; you can write down the words, but without the tune, it is impossible to know how to perform it. Likewise, it is impossible for any collection of texts, even one as superlative as the Posen Library, to recreate the experience of Jewishness in our time.

Indeed, the structure of the book acknowledges this; for as much as it includes, it is conscious of excluding a hundred times more. An anthology that includes one page of Humboldt’s Gift is effectively an invitation to read all 500 pages of Humboldt’s Gift. So too with all the single poems by prolific poets, the one scene from five-act plays, the one essay by a major intellectual. Long as it is, Volume 10 of the Posen Library is a kind of ideal reading list, pointing the way to more Jewish reading and looking and thinking than any one person could manage in a lifetime.

And even if you read it all, you would still be missing the melody, what Lionel Trilling called “the culture’s hum and buzz of implication,” which is constituted by the whole experience of living in a certain place and time. For example, most Americans, including American Jews, would surely say that comedy is one of the most important forms of Jewish expression; yet the names of Woody Allen and Jerry Seinfeld don’t appear in the index to Volume 10. In other words, there is a permanent gap between text and life, text and practice.

This gap, too, is a very familiar part of Jewish history: It is the gap that the Gemara (literally, “completion”) tried to fill for the Mishnah, as the civilization that produced the oral law grew more distant and harder to comprehend. It is tempting, then, to imagine the legions of commentary that might grow up around the Posen Library. Future readers will have to gloss words and references, and point out omissions, and explain historical background, and draw comparisons to their new world—just as the Amoraim did for the Tannaim.

The difference, of course, is that the Talmud was fuelled by the deepest kind of religious commitment—the certainty that, in expanding and exploring the Torah, the rabbis were doing God’s will. The terms in which the Posen Library is conceived are almost the opposite of this. Here we are dealing with human artifacts, with a Jewishness that is not legal and precise but cultural and diffuse. Can such a Jewishness compel the attention, and sacrifice, needed to sustain it? The Ozes, and implicitly the editors of the Posen Library, say yes; the future of more than our books depends on the answer.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.