Around Reading

After two years and 100 weekly “On the Bookshelf” columns about new books, assessing the impressive breadth of Jewish letters today

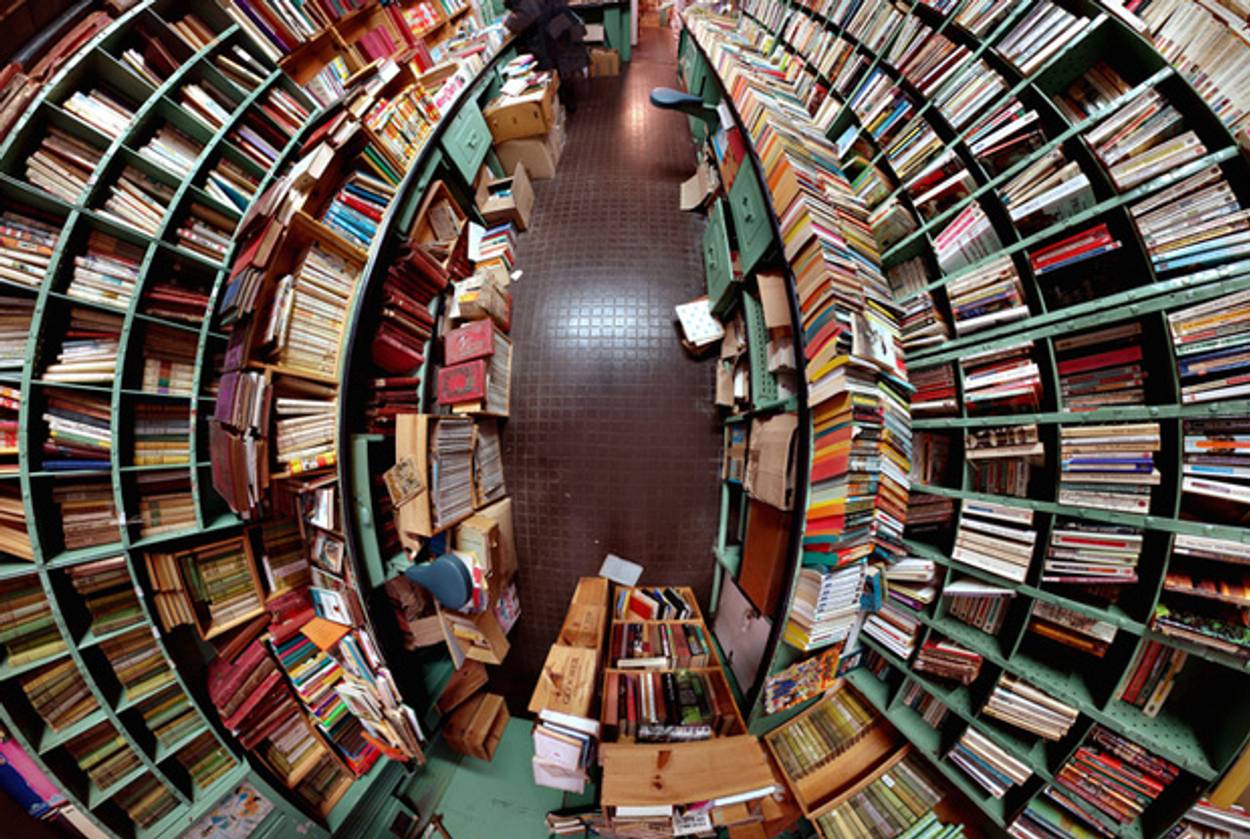

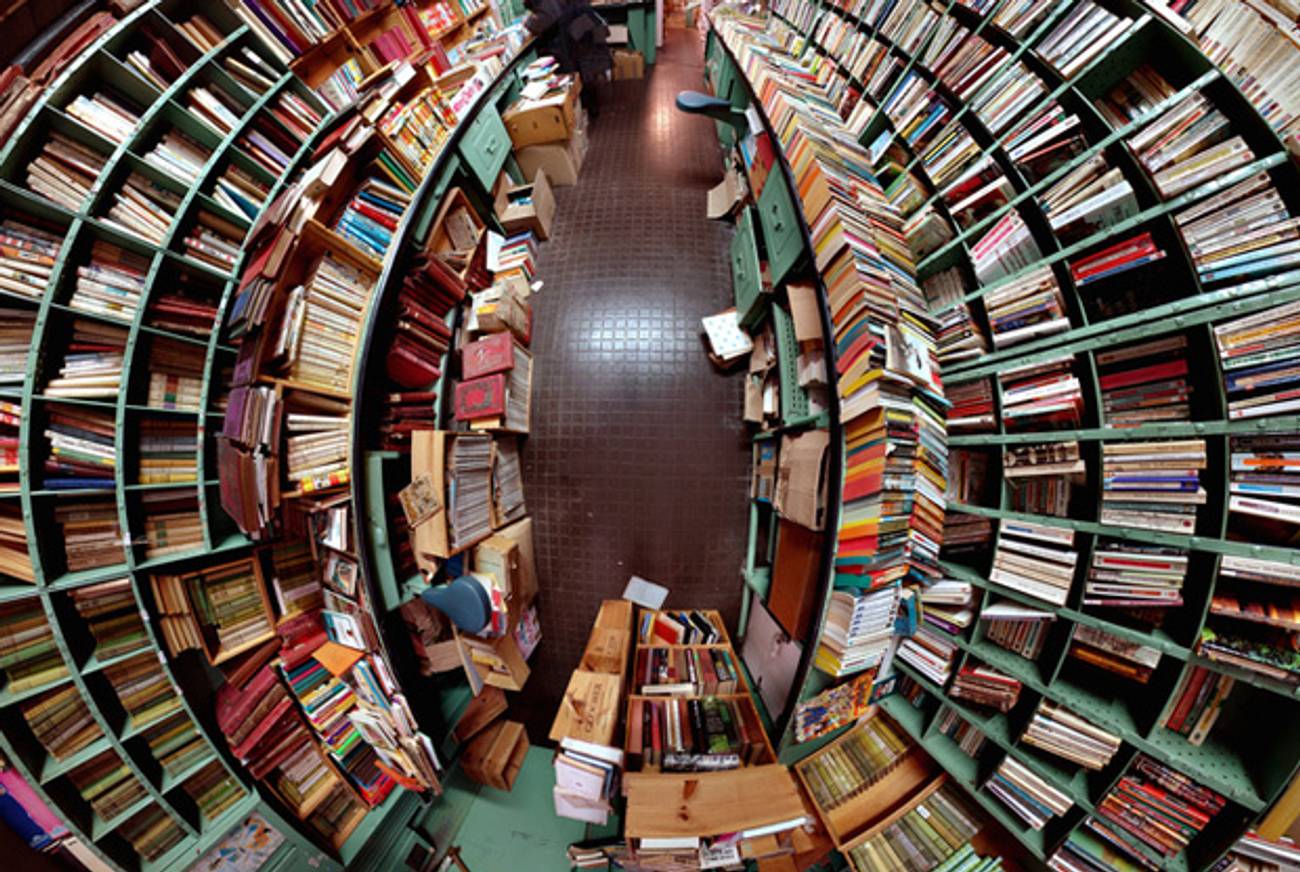

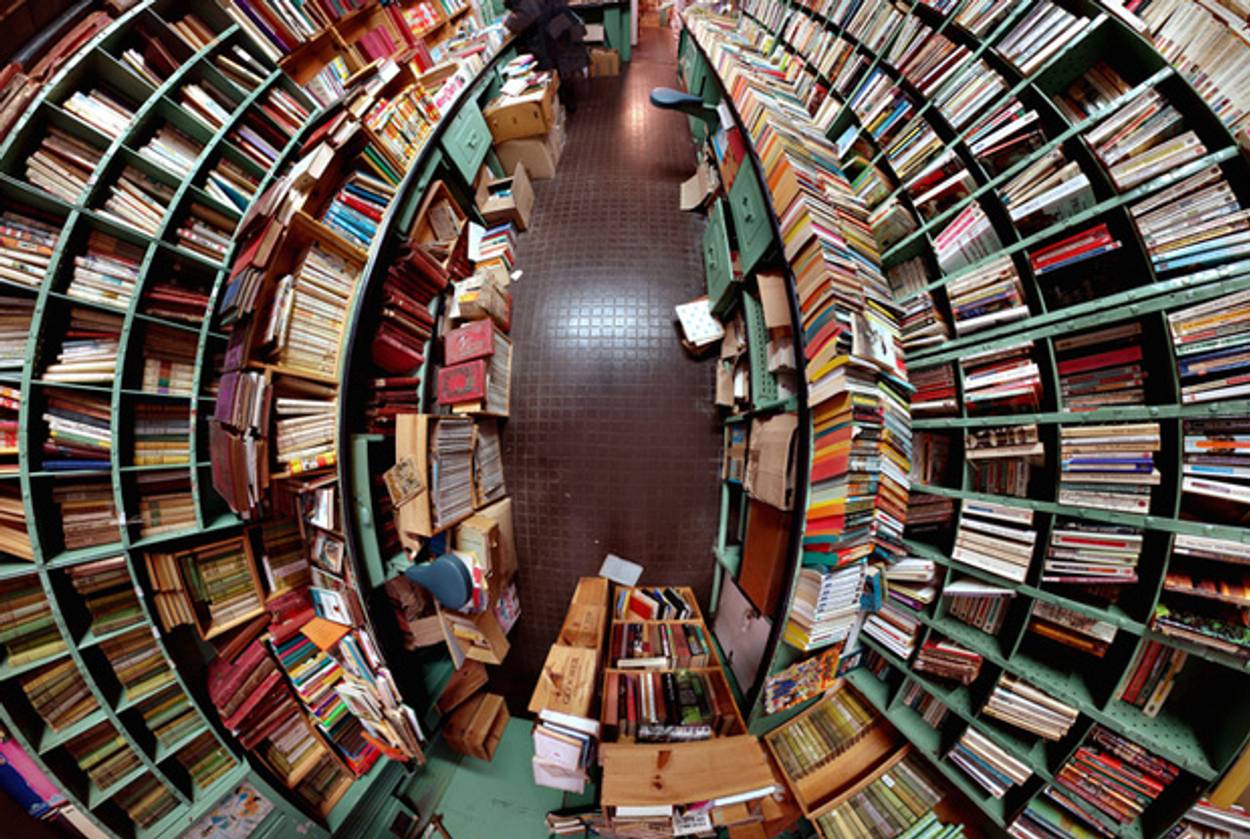

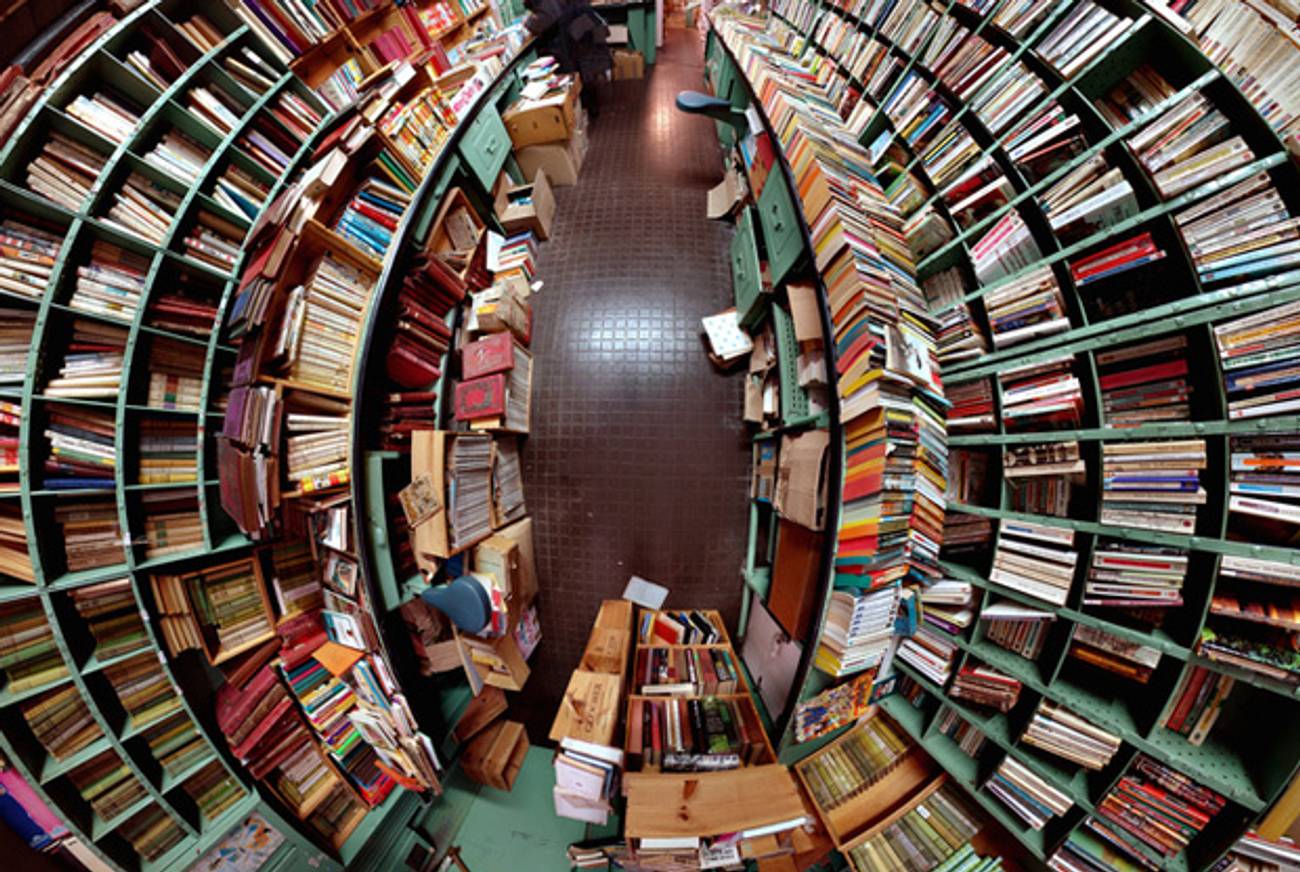

Books aren’t dying. They don’t even have a case of the sniffles. Between June 10, 2009, and Aug. 11, 2011, I wrote a hundred weekly “On the Bookshelf” columns for Tablet Magazine. Each covered eight to ten books, virtually all of them published within a month of the column date. Over the course of two years, these columns dealt with a total of 874 new books—yes, I went back and counted—each one printed, bound, and available for sale.

That’s a lot of books but still a tiny fraction of the world’s overall literary output. (In the United States alone, 302,410 new books were published in 2009, according to one industry source, and that’s not including public domain reprints and other “non-traditional” titles.) Even if I covered more than most magazines or newspapers did during those two years—and as narrow as my focus was on titles with some connection, however tenuous, to Jews or to Judaism—“On the Bookshelf” was hardly exhaustive. Every month I had notes on another two dozen titles that would have been relevant to a column with more time and space, and there were always plenty of worthwhile books, like Sam Lipsyte’s The Ask and Nadia Kalman’s The Cosmopolitans, that I would realize I’d missed only when they turned up in articles by other Tablet contributors.

A voracious reader could plow through the titles mentioned in “On the Bookshelf” at a clip of a Jewish book every day—Shabbat and Yom Kippur included—and would still end the year nearly a hundred titles behind schedule. And this without tackling, say, A Lethal Obsession, Robert Wistrich’s 1,200-page history of anti-Semitism, or Adam Levin’s 1,030-page debut novel, The Instructions. And while the number of books I dealt with in the column doesn’t qualify me as a budding Harold Bloom—who boasted, absurdly, that he was capable of reading up to 400 pages an hour—it does show that the publishing industry isn’t a corpse but a firehose.

Which is why I say that I “covered” the books: I didn’t read most of them. I served up an angle, or joke, or context for each title, based on what I could glean from skimming a galley, reading press releases and promotional excerpts, cribbing from the book publishing-industry trade magazines Publishers Weekly and Kirkus, or from a trawl of the blurbs, blogs, reviews, and interviews that proliferate on the Internet. Though “On the Bookshelf” has now been shelved, capsule book reviews continue to appear in the quarterly magazine Jewish Book World. Despite critics’ best efforts, though, the sheer number of new books being published makes even the sort of minor public acknowledgment I gave more than almost all authors can expect.

Some would gripe that many authors don’t deserve even this much recognition. And they probably don’t, when all they’re doing is churning out windy, under-researched polemics about the Middle East, or exploiting the tragedy of the Holocaust to gin up sales of undistinguished genre fiction, or cut-and-pasting yet another Bernard Madoff exposé in pursuit of a quick buck. But, as far as I could tell, even if most of the books covered in “On the Bookshelf” were far from immortal masterpieces, very few of them were without any merit whatsoever, without appeal to some readership, however niche.

You simply can’t publish this many books without producing at least a few original insights. Take the subject of Jewish sexuality, which seems like it was done to death a decade ago. Among the more unexpected books released in the past two years in this area are the first English-language history of a crucial German-Jewish condom magnate, a detailed and readable biography of the radical sex theorist Wilhelm Reich, and an unusual and impressively learned study of the representation of sexuality in the pseudepigraphic texts of ancient Jews and early Christians. New anthologies edited by Erica Jong, Danya Ruttenberg, and Amy Neustein have meanwhile offered insights into contemporary Jewish women’s sex lives, into the theology of Jewish lovemaking, and into the problem of pedophilia in Jewish communities. The voices of queer Jews have been heard much more loudly than ever before thanks to recent releases like Torah Queeries, a collection of Bible commentaries from LGBT perspectives; Andrea Myers’ The Choosing, a lesbian rabbi’s memoir; Keep Your Wives Away From Them, on the challenges faced by Orthodox lesbians; and Balancing on the Mechitza, about transgender Jews. However much you thought you knew from reading Portnoy’s Complaint and Fear of Flying about the ways Jews get off, this flurry of publishing shows how much more there is to discover.

The same could be said about Jews in sports. Even the most fanatical Jewish-baseball savant would learn something from Mark Kurlansky’s Hank Greenberg, Aaron Pribble’s Pitching in the Promised Land, Rebecca Alpert’s Out of Left Field, and Richard Michelson’s book for kids, Lipman Pike. And I find it difficult to believe that anyone knows so much about the legacy of Jews in professional basketball, bullfighting, and sports journalism not to be at least a little enlightened by Douglas Stark’s The SPHAS, Bart Paul’s Double-Edged Sword, and John Bloom’s There You Have It, respectively.

There were scores of contemporary Jewish novels, both highbrow and lowbrow, including important new work by Philip Roth, Cynthia Ozick, David Grossman, Allegra Goodman, and Gary Shteyngart. Dozens of first novels appeared, too, by the likes of Austin Ratner, Julie Orringer, Sam Munson, Jacob Paul, Avner Mandelman, and Sharon Pomerantz—any one of whom might turn out, two or three more novels down the road, to be as powerful a literary force as a Roth or an Ozick.

The productivity is nothing short of staggering, when you stop to think about it. Imagine you want a book on Maimonides, the medieval doctor, theologian, and philosopher, and you don’t want an old dusty one from the mid-2000s. You can still choose from no fewer than half a dozen brand-new or newly reissued biographies, released since mid-2009, almost all of them aimed not just at professional scholars but also at the smart general reader. And that’s not to mention focused analyses of Maimonidean thought, books in Hebrew and other languages, or new editions of the man’s own works.

Maybe all that the proliferation of Rambam books reflects is that there are now hundreds of Jewish Studies scholars at universities around the world whose positions require them to churn out new monographs as often as possible, along with a substantial number of nonacademic Jewish authors and journalists, both religious and secular, who can’t resist grappling with a figure as influential as Maimonides. But this itself is something to celebrate—when, in history, have there ever been more professional, full-time Jewish writers?—and it also suggests that the common pool of knowledge about Jewish life, culture, and thought will continue to grow deeper, year by year, and page by page.

Literary superabundance does present a real threat to authors: As more books are published, less attention can be devoted to each one as an individual achievement. So, one suspects it’s with them that the gripes about the death of the book originate. But from a committed reader’s perspective, there has never been a more vibrant literary marketplace: Books are more plentiful, cheaper, and easier to find than ever before. Anyone kvetching about the death of the book is just giving him- or herself a half-assed excuse for not reading more of them. The rest of us are busy enjoying a literary renaissance.

Josh Lambert (@joshnlambert), a Tablet Magazine contributing editor and comedy columnist, is the academic director of the Yiddish Book Center, Visiting Assistant Professor of English at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and author most recently of Unclean Lips: Obscenity, Jews, and American Culture.

Josh Lambert (@joshnlambert), a Tablet Magazine contributing editor and comedy columnist, is the academic director of the Yiddish Book Center, Visiting Assistant Professor of English at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and author most recently ofUnclean Lips: Obscenity, Jews, and American Culture.