Avi Shlaim’s Fantasy Land

In ‘Three Worlds: Memoirs of an Arab-Jew,’ his autobiography-cum-history of Iraqi Jewry, historian Avi Shlaim’s life unfolds like a fairy tale

Original photo: A.P.H. Hotz/Royal Geographical Society via Getty Images

Original photo: A.P.H. Hotz/Royal Geographical Society via Getty Images

Original photo: A.P.H. Hotz/Royal Geographical Society via Getty Images

The pampered princeling toddles from age zero to 4 around his palatial home—featuring seven toilets, three bathrooms, vast living rooms with “precious Persian rugs,” a lush garden—watching his beautiful mother, Saida, while away her evenings at poker with Iraq’s high and mighty as hubby Joseph, a rich businessman, parties into the night in downtown Baghdad. Otherwise, the family reclines on the shores of the Tigris feasting on sumptuous picnics as nannies shoo away the flies (and, presumably, the local riffraff). The Shlaims “were well-integrated into Iraqi society,” he tells us.

Iraq turns anti-Jewish and xenophobic and the Shlaim family—including 5-year-old Avi—flies to the impoverished State of Israel, where they eventually wash up in a cramped apartment in a gray tenement, their wealth and status left behind in Baghdad. Joseph, after serial heart attacks, is unemployed, lost, and broken, while Saida, to keep starvation at bay, becomes a telephonist. The dominant, absorbing Ashkenazi society regards the incoming immigrants from Arab lands (mizrahim, easterners) as inferior semibarbarians. In school, Avi is taken for a dimwit (though at one point he writes, “I did not experience direct discrimination and I did not encounter overt racism”). Nonetheless, he develops an inferiority complex and underperforms academically (“I was indolent, introverted, cut-off, phlegmatic to a rare degree”).

But “Nana” and Uncle Isaac ride to the rescue. Now 15, Shlaim is sent off to London, where he gradually blooms and even acquires a girlfriend. He briefly returns to Israel to serve in the IDF (“[It was] the high point of my identification with … Israel,” he writes). Then he returns to England, where he soars: Jesus College, Cambridge, and the University of Reading, where he matures as a historian, ascends to an Oxford professorship and, along the way, publishes half a dozen well-received books, including Collusion Across the Jordan: King Abdullah, the Zionist Movement, and the Partition of Palestine, and The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World. He even marries the great-granddaughter of a British prime minister.

Three Worlds tells us what makes Avi run. His mizrahi roots and experience produce a raw nerve, the emotional and psychological wellspring of his later oeuvre and politics.

He interweaves his personal story (until the age of 20) with the history of Iraq and the Arab-Israeli conflict. His personal story is moving, and it is told with atypical, engrossing candor. He describes his mother’s forced marriage, at 17, to 41-year-old Joseph; rebelling, she briefly ventures on a hunger strike and is raped on her wedding night. Relations with his sisters are rocky and overclouded with misogyny (“Abi [Avi] is the honey, and you are the peels of the onion,” says Grandma). There is a cold, distant relationship with his father. Saida and Joseph divorce. A would-be Mossad recruiter fondles Saida. Uncle Isaac the benefactor purloins a sixpenny tip left by a customer for a waiter, etc.

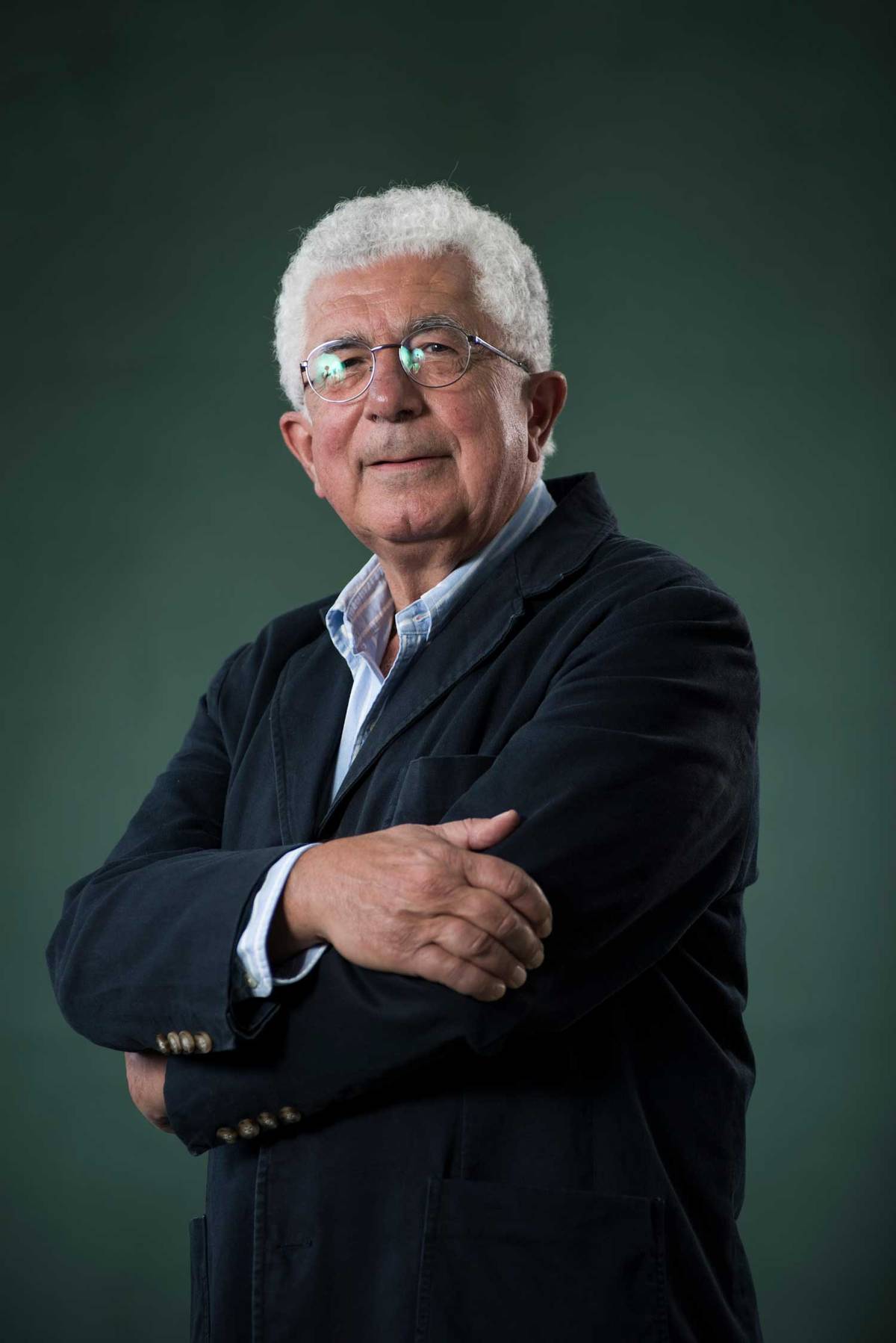

Courtesy Avi Shlaim

Shlaim comes to define himself as an “Arab-Jew,” like some of Israel’s mizrahi intelligentsia—Yehuda Shenhav, Sammy Shalom Shitrit—who sired the Keshet Hamizrahit (the Mizrahi Democratic Rainbow Coalition) movement. Trying to better the social and economic condition of the second- and third-generation mizrahim, they believe that the (alleged) maltreatment of their parents when they arrived in Israel was merely one facet of the Ashkenazi contempt for the Arabs in general.

It was the mizrahim’s bitter sense of grievance that propelled Menachem Begin and the Right to power in 1977—and, passed down the generations, continues to maintain the Right (and Netanyahu) in power and, in part, underwrites their current effort to subvert Israel’s liberal culture and infrastructure. In Shlaim’s case, the personal affront and alienation ultimately morphed into anti-Zionism and sympathy for the Palestinians, who in his repeated tellings can do no wrong.

But given Shlaim’s antipathy to Israel, which repeatedly and unmistakably surfaces through Three Worlds, as it has done, increasingly, through the rest of his oeuvre, one point needs clarification—Shlaim’s name. Not the “Shlaim,” which apparently derives from an unidentified German ancestor, but the “Avi.” Why does he persist in using this common Israeli name, usually an abbreviation of Avraham? As a self-styled “Arab-Jew,” perhaps “Ibrahim,” as he is designated in Saida’s old British passport, or “Ibri,” or “Abi,” as he was called as a child, would be more fitting? And why does Three Worlds sport a full-page photo of the young Shlaim in IDF uniform standing proudly next to Grandma Mouzli Obadiah? Is it that Shlaim is reluctant to completely part with his Israeli identity, perhaps because it usefully underlines his status as a Zionist apostate within academe, or is it because he however grudgingly continues to discern something positive in the Israeli experience?

Shlaim writes that he has placed his family’s story “within the broader context … [of] the history of the Jewish community in Iraq.” Indeed, at various points in Three Worlds he seems to say that he is relating the story of all the Arab world’s Jewish communities, not just Baghdad’s or Iraq’s.

But he isn’t. Three Worlds tells the story only of a wafer-thin layer of rich Baghdadi Jewish families. There is almost nothing in the book about the majority of Baghdad’s 80,000-100,000-strong Jewish population, the middle or lower middle classes and the poor. And it tells us nothing at all about the tens of thousands of Jews who lived in the Iraqi hinterland, especially in the Kurdish north.

How did Iraq’s Jews fare? In a gross understatement, Shlaim concedes that “the status of the Jews of Islam could be contentious at times.” He hardly mentions the bloody pogroms, the bouts of oppression and the permanent subordinate status and humiliation of the Jewish communities that lived between Morocco and Persia in the 14 centuries since the rise of Islam.

While it does appear that the Jews of Mesopotamia fared better than most of their sister communities, Shlaim exaggerates to the point of distortion: “Iraq was a land of pluralism and coexistence.” Unlike Europe, “in Iraq … there was an old tradition of religious tolerance … The overall picture … was one of religious tolerance, cosmopolitanism, peaceful coexistence and fruitful interaction.”

It is true that the Jews of Iraq—or Islam in general—did not suffer genocide. But in Iraq, as in all the Muslim lands, Jews (and Christians) were dhimmi, second-class subjects. So it was in Baghdad during Arab, Mongol, and Persian rule in the Middle Ages and so it was in the following centuries. Periodically Jews were persecuted (as under the caliphs Omar II ibn ‘Abd al ‘Aziz, Harun al Rashid, al Mutawakkil and al Muqtadi), forced to pay special taxes, and wear identifying (usually yellow) tags or garb.

In 1333 and 1344 Baghdad’s synagogues were destroyed. By the 15th century, almost no Jews remained in the city. Under the Ottomans, who ruled Iraq from the 16th century until 1917, the picture was mixed, and during the 19th century the Jews came to dominate Iraq’s economy. In the years of British mandate rule (1921-32) the Jews prospered, with a Jew—Sasson Effendi—even serving as finance minister. But Iraqi independence brought a swift and permanent decline in their status. Anti-Jewish laws were enacted and Jews were dismissed from government posts. During 48 hours in June 1941 in Baghdad, some 200 Jews were slaughtered and hundreds raped by Muslim mobs and soldiers, as police and government officials looked on, in what became known as the Farhud—an event for which Shlaim incredibly blames the British.

Thereafter, the Iraqis generally regarded their Jews with suspicion, against the backdrop of the growing conflict between Jews and Arabs in Palestine. Eli Amir, an Iraqi Israeli writer of Shlaim’s generation, has described how Muslim children regularly beat and chased him and his friends down Baghdad’s alleyways as they made their way home from school. During the 1948 war and its immediate aftermath, many hundreds of Jews were arrested and sent to detention camps, Jews were systematically harassed (including Shlaim’s family), robbed of their assets and businesses, and thrown out of jobs, schools, and university. A handful were tortured and hanged. Jews were then barred from leaving Iraq.

But in March 1950 the government changed policy and announced that Jews could leave if they gave up their Iraqi citizenship. This was followed up in March 1951 with a regulation freezing—meaning confiscating—the assets of all Jews who had renounced Iraqi citizenship or left the country since 1948. Israel semiclandestinely organized the community’s mass departure, and 123,500 Iraqi Jews resettled in the Promised Land by the end of 1951, while a few thousand more made their way to the West.

The Shlaims—why is not adequately explained—headed for Israel. Not adequately, because the family was non-Zionist, perhaps anti-Zionist. “Zion had little allure,” Avi tells us. “Zionism was an Ashkenazi thing. It had nothing to do with us,” he quotes his mother as saying. (Later, he writes: “The Zionist movement was a colonial-settler movement”; “Zionism aimed to build a Jewish Sparta in the Middle East.” Aimed?) For his grandmothers, Shlaim tells us, Iraq was “the Garden of Eden,” “the beloved homeland”—and the Land of Israel was “a place of exile.” They could well have said: “By the waters of Zion, there we sat down, and there we wept, when we remembered Babylon.” One can only wonder at what would have happened to Iraq’s Jews, had they stayed, under the Baathist colonels and Saddam Hussein.

Shlaim writes that it was “the push of Iraqi xenophobia and the pull of the newly born Jewish state” that resulted in the mass exodus of 1950-51. But throughout the book he paints a less balanced, more lurid picture that in effect attributes the mass departure to Zionist lies, manipulation, and terrorism, with the Iraqis playing only a secondary role.

In particular, Shlaim zeroes in on five explosions in Iraq during 1950-51 directed against Jewish or Jewish-related targets, one of which, at the Mas’uda Shemtob Synagogue, caused four fatalities. The Iraqi government quickly blamed the Zionist underground, set up after the Farhud by local Zionists and guided by agents from Israel/Palestine. The bombings, said the government, were designed to encourage the Jews to leave. The Iraqis subsequently tried and hanged two underground operatives, Yusef Ibrahim Basri and Shalom Salih Shalom. Many Iraqi Jews, including the Shlaims, believed the government’s explanation, and some continue to believe it today. Israel consistently denied any involvement by its agents and said the bombers were probably Iraqi government agents or Muslim extremists.

GL Portrait/Alamy

Shlaim claims to have solved the mystery. Three of the bombings “were the work of the Zionist underground,” he concludes. But in effect he goes further and blames Israel for the fourth, the lethal Mas’uda Shemtob bombing, as well. Basri and Shalom were controlled by an Israeli intelligence officer based in Iran named Meir Max Binnet, Shlaim writes. And the lethal attack at the synagogue was carried out (separately) by a Syrian criminal who was dispatched by an Iraqi police officer who had been bribed to mount the attack by the Zionist underground, he writes. Shlaim bases these findings on statements made by an Iraqi Jew some 60 years after the event, on Iraqi journalistic reports, and on an unheaded, undated, unsigned page in Arabic purportedly purloined from an Iraqi police report on the bombings.

It all sounds pretty convincing (if repetitive), but this historical documentation is inconclusive at best. One apparent error in Shlaim’s narrative stands out. In trying to pin Israel’s colors to the bombings, he writes that Binnet in 1954 was “in charge” of a subsequent (proven) Israeli sabotage operation using a cell of local Egyptian Jews, in which U.S. cultural centers and other targets in Cairo and Alexandria were bombed with the purpose of causing bad blood between Egypt and the West (the episode known in Israel as essek habish—the unfortunate business). The cell was caught and its members were jailed or executed. Binnet was also picked up and committed suicide. The problem with Shlaim’s account is that Binnet was apparently not involved in the sabotage operation in Egypt. He was an independent spy. The bombing was organized and run by someone else but Binnet was picked up incidentally due to a compartmentalization failure.

“Having lived as a young child in an Arab country, I was aware of the possibility of peaceful Arab-Jewish coexistence … My Iraqi background thus helped me, as I grew up, to develop a more nuanced view, based on empathy for all parties locked into this tragic conflict,” writes Shlaim. Unfortunately, he continues, the idea of a two-state peace settlement, based on partitioning Palestine, is dead. Shlaim attributes this death solely to Israel and Israeli policies, particularly the settlement enterprise, which, over the past 50 years, has planted more than half a million Jews, some of them messianic fanatics, in the midst of the 3 million-strong Palestinian Arab population of the West Bank. Israel has, and will likely have in the future, neither the will nor the power to uproot the settlers.

I agree with Shlaim that the two-state solution model is dead. What he fails to mention is the initial and even more compelling cause of the death of the two-state solution: Palestinian Arab rejectionism. The Palestinians have displayed remarkable consistency in rejecting the two-state solution: They said “no” to the Peel Commission partition proposal in 1937 (which awarded the Arabs 70% of Palestine) when Haj Amin al-Husseini ruled the roost; they said “no” to the U.N. General Assembly’s partition resolution of November 1947 (which proposed Palestinian statehood on 45% of the land); PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat said “no” to the partition proposals of the year 2000 (the “Clinton Parameters”) that awarded the Palestinians a state on 21%-22% of Palestine; and current Palestinian Authority “President” Mahmoud Abbas failed to respond (i.e., said “no”) to Israeli Premier Ehud Olmert’s partition proposals, which were akin to Clinton’s, in 2007-08.

The fundamentalist wing of the Palestinian national movement, Hamas, which won the Palestinian elections in 2006 and is still the most popular Palestinian party, rejects out of hand any talk of partition. It aims, so says its charter, clearly, to eradicate Israel and replace it with a Sharia-ruled state between the Jordan and the Mediterranean. And while the Palestinian Authority, dominated by the Fatah party, occasionally pays lip service to the two-state idea, it, too, covets all of Palestine (why else insist on the refugees’ “right of return,” which, if realized, would create an Arab majority?). Partition is not on the Palestinian agenda today, if it ever really was.

So what does Shlaim propose? A one-state solution—a democratic binational state, ruled jointly by Palestine’s Arabs and Jews. The problem is that neither Palestine’s Arabs nor its Jews support this unworkable idea, especially given the 120-year history of war, terrorism, and repression. For a model of this kind of solution, Israelis, Palestinians, and helpful foreign interlocutors need look no further than the internally fractured Lebanese state on Israel’s northern border, which is dominated by Hezbollah. There is too much blood, and bad blood, between the two peoples, not to mention abysmal religious, cultural, and social differences—and yes, racism, on both sides—to produce a version of Belgium on the Mediterranean.

Shlaim’s idyllic vision, based on the social and economic mingling of upper crust Arabs and Jews in Baghdad during a brief period of time in the 1930s, is not a precedent or pointer to anything. My prediction? Were a one-state solution ever tried, it would collapse in anarchy and drown in rivers of blood, compared to which today’s violence is a mere trickle.

Three Worlds is very readable, like everything that Shlaim writes. A good editor would have deleted its innumerable repetitions—and he or she may also have caught some of its outlandish factual errors: “seven Arab armies invaded” Palestine in 1948 (in fact, it was four); “at the end of 1948” Israel’s population was “650,000 of whom 150,000 were Arabs,” (in fact, there were 700,000 Jews and somewhat more than 100,000 Arabs), to give just a few examples.

Early on in Three Worlds, Shlaim recalls that his “elders’” viewed Israel, before the family left Iraq, as “a small, faraway country of which we knew little.” The words echo the appeaser Neville Chamberlain’s dismissive designation during the 1938 Munich crisis of Czechoslovakia, which he was about to sell down the river, as “a far-away country … [inhabited by] people of whom we know nothing.” Is it possible that subconsciously Shlaim is here signaling his desire, or what he assumes is or will be the West’s desire, to sell Israel down the river?

Benny Morris is an Israeli historian and the author, most recently, of Sidney Reilly: Master Spy (Yale 2022).