A Cannes Diary

With the pandemic receding, war dragging on in the East, and accusations of misogyny flying, Tablet’s European cultural correspondent files daily dispatches from the world’s most famous film festival

The best Cannes Festival of the last decade has come to a triumphant conclusion. Aside from my own personal disappointment with the Wes Anderson submission, Asteroid City (Wes, if you are reading this, I also live in Paris and await your dinner invitation!), the selection of films this year was truly a great and lovely bounty. In fact, the selection was so good this year that one did not have the time to catch all the buzzed-about films. My theory is that we are still dealing with the effects of the COVID bottleneck, with multiple productions stalled and some filmmakers deciding to hold off on submitting their films to international competitions because of it.

The Palme d’Or went to French director Justine Triet for her courtroom drama Anatomy of a Fall. That was a surprise to me, as Anatomy of a Fall was the only strong contender that I assumed I didn’t need to watch. One cannot watch all 60-plus films in 10 days while keeping one’s sanity and social and work obligations, so every festivalgoer has to make predictions and choices. I am usually fairly good at guessing which films are worth seeing, but this year I bet badly and missed the competition winner.

Anatomy of a Fall follows the aftermath of a renowned writer being accused of killing her husband. Triet is now only the third woman to win the Palme d’Or in the entire 76-year-long history of the festival. She took to the podium at the award ceremony to deliver a blistering assault on the French government’s controversial pension reform plans. Her diatribe was unpleasant enough that the French minister of culture was forced to publicly respond that she was “surprised.”

The rigorous adaptation of the 2014 Martin Amis Holocaust novel, Zone of Interest, which I knew all along would be one of the main prize winners despite my own ambivalence about it, did not disappoint. The film was awarded the runner-up Grand Prix, thus honoring the legacy of the great writer a week after his death and propelling the film’s director, the very talented Jonathan Glazer, toward access to all the resources that he might need to make whatever he wants to for the rest of his life. Here’s hoping that Glazer doesn’t take another decade to finish his next project. It was also a good week for German actress Sandra Hüller, who played the insufferable wife of the Auschwitz camp commandant in Zone of Interest and starred in Anatomy of a Fall. Which must also be some sort of record.

The award for best actor went to Kōji Yakusho for his role as a toilet cleaner with a poetic soul in Wim Wenders’ Perfect Days. Or, as Le Monde described the film in the title of its review, “suit la routine quotidienne d’un poete des toilettes.” None of the cowboy films screened this year, whether of the gay or the deconstructionist variety, were garlanded with awards. Meanwhile, the best director prize was very fittingly given to the Vietnamese French gentleman Trân Anh Hùng for his luscious historical drama The Pot-au-Feu (La Passion de Dodin Bouffant). This touching and beautiful love story between Juliette Binoche (a cook) and Benoit Magimel (a great gourmand) was based on the equally mouthwatering classic, Marcel Rouff’s La vie et la passion de Dodin-Bouffant, gourmet (The Passionate Epicure).

Binoche and Magimel, who collaborate on cooking up these decadent meals, share a remarkable chemistry in the film, buoyed by the fact that they once lived together. The delectable scenes of beautiful French food being lovingly and slowly cooked in a countryside kitchen, bathed in golden light and filmed with remarkable grace, left me so hungry that I ran to the Majestic after the screening in order to have a meal by the same French chef who had cooked in the film. I also had to gently coax the billionaire that I was having a work meal with into purchasing a bottle of the same Bâtard Montrachet Grand Cruthat that Binoche and Magimel had shared on screen. The lunch bill came out to 1,800 euros. Cineastes and gourmands of the world, unite and go see this film if it is screening in your area!

Until next year, au revoir—see you on the red carpet in 2024!

Some of the changes that have transpired in Cannes since the conclusion of last year’s festival have been more welcome than others. The town’s marquee hotel, the belle époque era Carlton, has been triumphantly reopened after a lengthy refurbishment. The hotel has been transformed from a bastion of stuffy Old World elegance into a bastion of minimalist new money elegance by Cannes-born interior designer Tristan Auer. The space is now wide open and full of light-ochre tones, and the staff is now dressed in outfits that have been copied from Alfred Hitchcok’s 1955 To Catch a Thief, which actually took place in the hotel. Still, I am not the only one who prefers tradition: The prominent filmmaker with whom I had a drink in the hotel’s manicured garden courtyard last night compared the new version to an upscale Turkish seaside resort, while my wife opined that it now more resembled a high-end Moroccan or Tunisian palace.

The Russian pavilion, which has for years been the second-biggest of the national pavilions (behind only the United States), has this year been transformed into the Saudi Pavilion. Saudi money and influence were incidentally to be seen all around the festival this year. Meanwhile, the management of the Majestic Hotel had recently begun employing dedicated teams of falconers to keep pigeons away from the well-heeled guests. When I visited the hotel pool, I noticed a medium-size Harris’s hawk perched in a palm tree, taking in the festivalgoers, producers, and hedonists lunching and making deals. The presence of the hawk ensured that not a single pigeon or seagull was to be found in sight. Yet a gathering of even more exquisite birds of paradise could be seen at the table next to my own.

I will remain forever grateful to that flock of Italian models. A dozen of the most exquisite ladies had ordered a round of champagne, and yet, suddenly invited out to a bacchanal on a yacht, they summarily paid their bill and decamped without so much as touching the bubbly. I had already spent upwards of 400 euros on Champagne at lunch in order to toast the conclusion of the festival, as well as to celebrate my wife having just received funding for her next two films. Thus the comely Italian birds—I use the term literally, as two of them were actually wearing elaborate red carpet dresses made entirely out of bird feathers—had inadvertently subsidized the first round of the final evening.

In fact, I had earlier been stuck behind one of the Italian bird-women while waiting to see Kidnapped from the Italian director Marco Bellocchio. This year, Italy has continued to honor its historical tradition of being a European film powerhouse. This year’s program presented a very respectable representation of Italian cinema. Alice Rohrwacher, one of seven women directors with films in competition, returned to the festival palace for a third time with La Chimera, a charming, if also plodding and overlong film about tomb robbers and a lovesick Italian archeologist. Who among us romantics could resist such an Italian drama? The audience at the premiere screening in the grand Lumiere theater surely could not. It rewarded the film with a nine-minute-long standing ovation.

For me personally, the more amusing, though much more self-indulgent, film in this year’s competition was Il Sol Dell’ Avvenire (A Brighter Tomorrow) from Nanni Moretti. I hasten to admit that I am in a very tiny minority of viewers who liked it. Moretti is a great filmmaker, who won the Palme d’Or 22 years ago for The Son’s Room and has made many other good films. Here, he plays himself as a boisterous, egotistical, imperious, irascible, tyrannical, and amusing elder statesman filmmaker. Nearing 70 years old, Moretti is considered to be a cinematic master, and masters are often allowed to get away with whatever they want. I liked this film precisely because it is by any standard unambiguously and totally awful.

Moretti (the director in the film) plays himself dealing with the totally tedious minutiae of producing the film, as well as the equally tedious minutiae of his long-suffering wife wanting to separate from him. The tedious film within the film relates to the drama of the Italian Communist Party under Palmiro Togliatti having to decide on whether to break its symbiotic relationship with Moscow over the 1956 Soviet invasion of Hungary. The subplot within the subplot is told in part through the travails of a troupe of Hungarian communist circus performers. A mere two elephants for the final Felliniesque circus scene are certainly not enough for Moretti—Moretti wants all four elephants! The over-the-top denouement of the film, filmed in central Rome, may have warranted those four elephants, but most people will not have stuck around for the ending, nor should they.

The Guardian’s eminent film critic Peter Bradshaw was scathing in his one-star review: “[Moretti’s] new film in competition is bafflingly awful: muddled, mediocre and metatextual—a complete waste of time, at once strident and listless. Everything about the film is heavy-handed and dull: the non-comedy, the ersatz-pathos, the anti-drama.” Still, even though I know Bradshaw is objectively correct, I rather enjoyed the spectacle of a surly, misanthropic, and insufferable elderly European aesthete acting out. I hope to do so myself one day when I become a surly, misanthropic, and insufferable elderly European aesthete.

Kidnapped is the third Italian film in competition. Unlike his younger countryman, Bellocchio, now in his early 80s, is not coasting on previous achievements. The renowned director has brought to the screen an adaptation of the infamous tale of the Catholic Church’s kidnapping of a 6-year-old Jewish Italian boy, Edgardo Mortara, from his family and having him raised by the church in 1857. The family maid had thought that the mildly sick little boy was dying and had baptized him in secret so that his soul would ascend to heaven. The baby survived the fever, and six years later, the maid would inform a priest of what she had done in confessional. At the time, the Papal States were governed by strict Catholic law, which held that a baptized child must be raised by Christian parents. The boy was raised under the personal patronage of Pope Pius IX, shown here as a malevolent villain, who rejected international pressure to return the boy to his traumatized family. “I do not care if every Rabbi in America condemns me,” he spits out upon being informed of international condemnation.

The Jewish father of the boy, a Bolognese Jew by the name of Momolo, has a passive and overcautious approach to the campaign to return his son—he even contemplates converting to Christianity to get the boy back—even as his wife is willing to fight to the death, refusing any compromise with the church. Edgardo is educated in the Vatican with some other Jewish boys who have been converted to Catholicism. This is a historically important story, and a decade ago, Steven Spielberg had put concerted effort into adapting it. The playwright Tony Kushner was supposed to be the scriptwriter, yet the project fell apart for numerous reasons, including the failure to find the right 6-year-old actor, as well as Spielberg’s ambivalence about not shooting the film in Italian. It is fascinating to imagine what would doubtless have been a very American, and possibly very kitsch, version of this very Italian story. Perhaps it is for the best that Don Spielberg abandoned the project.

Bellocchio, on the other hand, is interested in the story from an entirely Italian (rather than Jewish) point of view. Even as the portrayal of 19th-century Italian Jewish life is handled with delicacy and realism. The film frames the story as being a core part of Italian history, positing that the international opprobrium heaped on the Vatican helped precipitate the eventual collapse of the Papal States and the circumscription of the pope’s earthly powers. When the priest from the Inquisition department who took the boy away is put on trial, the family’s revolutionary lawyer tells the bewildered father that it is important that they have just lost their preliminary appeal because the case will go down in history as a blow against the Papal States. Needless to say, this was not much comfort to the family. This is a deeply worthy film, yet somewhat schematically historical, and outside of half a dozen poignant moments, such as when the young Jewish priest Edgardo is confronted by his revolutionary brother, or as when as a boy he tries to rip the nails out of the feet of a statue of Christ in order to reconcile his new life in Vatican with his old beliefs as a Jewish kid—this aesthetically sumptuous yet somewhat placid film lacks authentic emotional depth.

Incidentally, Kidnapped should be acknowledged as being tied for the status of the “most Jewish movie at Cannes this year” with Cédric Kahn’s The Goldman Trial, which follows the 1975 trial of a French- ewish bank-robbing revolutionary for the alleged killing of a pair of pharmacists in a robbery gone awry. That is an old fashioned court procedural drama and it was the opening film of the Directors’ Fortnight program. Goldman’s two lawyers—a young French Sephardi and a young French Ashkenazi—argue about how much to play the Jewish card during the trial.

After having a great time arguing with the German film critic yesterday on the merits of Glazer’s Zone of Interest, I ran into him several hours later, dancing with a beer in hand at the German party on the beach. He slapped me on the shoulder and told me that I was a good man. Or at least I think that is what he said—the DJ was blaring Britney Spears very loudly. It was when my wife and I heard 500 Teutonic voices pronouncing “Hit me baby one more time” in unison that we were forced to flee. Relocating a few blocks away to a private bacchanal in the rented hotel suite of a production company owned by Russophone French friends, I somehow spent the rest of the night arguing about Ukraine, explaining the threat of Moscow’s war to Polish security concerns to a Polish producer who was markedly less concerned than she should have been. The industry market section of the festival has shuttered for the season, and the industry people are starting to go home. Cannes has claimed a record number of around 14,000 accreditations this year, and over the last few days, the bigwigs have begun to trickle out. The evening crowds along the Croisette are becoming more manageable.

In the morning, despite my better instincts, I attended a second screening of Wes Anderson’s Asteroid City. I had really hoped that my initial response to the film was wrong—I remain a committed fan of Anderson’s fussy, overly ornate, sensitive and often raucous vision. The film deserved a second viewing.

Sadly, the second viewing didn’t help. More than any other major filmmaker of the last few decades, Anderson continues to carry forth his personal fantasia from film to film, having already developed his style, concerns, and crew. The whimsy of his lovingly constructed worlds always threatens to become cloying, and here it does more than threaten. My original reaction was seconded by many critics—the word “turgid” appears with regularity in the early reviews—though the film, like all Anderson productions, will also have its partisans. For me, it’s one of the director’s bad films, alongside The Darjeeling Limited (which was arguably better) and The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou.

The German filmmaker Wim Wenders, an artist whose emotional register and concerns have often been compared to those of Anderson, has a pair of films in Cannes this year. For the record, the 77-year-old looked absolutely splendid on the red carpet with his custom-made hybrid robe/frock and a four-ended propeller bow tie. The Wenders film that everyone at Cannes one wanted to see, and which only played once in 3D, was his new documentary of the life of artist Anselm Kiefer. Which, of course, despite all of my concerted efforts, was not the Wenders film I had a chance to attend (Kiefer’s exhibition at the Venice Biennial in the Doge’s Palace, by the way, was awe-inspiring).

Instead I saw Perfect Days, which tells the story of a pre-retirement-aged Japanese toilet cleaner, who lives a regimented life of cleaning city toilets by day and experiencing the quiet pleasures of life by night. It is charming, and it also possesses a visually pleasing style, with lots of light blue hues and warm orange glows. The genre of auteur films about working class characters is an elite film festival cliché—and, as Ken Loach also has a film premiering in the competition’s last days this year, I will doubtless receive my dose of sentimental valorization of the working man before the conclusion of the festival.

Yet Perfect Days (the film is named after the Lou Reed song, which our protagonist plays off of old cassette tapes in his truck), is about the aesthetic pleasures of a man who cares about books, art, music, and his minor rituals, such as consuming his daily lunch on the same park bench every day. Some Japanese hipsters grow old and take on menial jobs but do keep their soul into late middle age. “The new film’s humane, hopeful embrace of everyday blessings is enough to make it Wenders’ freshest, most rewarding and arthouse-friendly fiction feature in close on 30 years—following a 21st-century run of dusty or disheveled works dwarfed by the artistry and elan of his recent documentary work,” judges the Variety critic Guy Lodge. Which is absolutely right.

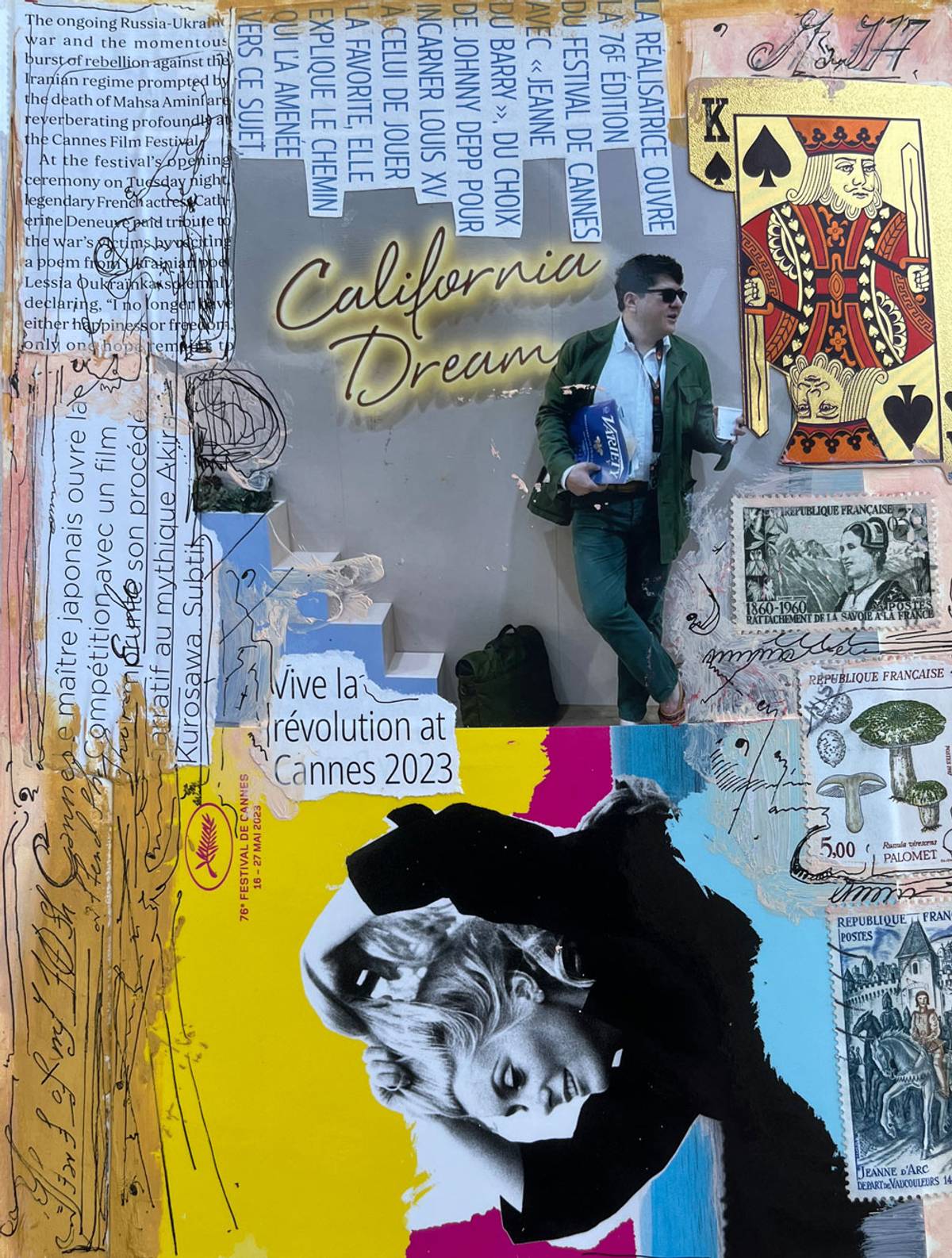

Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest, the aesthetically meticulous and emotionally frigid Holocaust film, continues to be one of the most talked about and divisive pictures of the festival. It has garnered one of the highest aggregate ratings culled from the reviews of the assembled film critics, and has created about as much controversy here as any film not starring Johnny Depp (Jeanne Du Barry) or his starlet daughter Lily-Rose Depp (The Idol).

Today in the press room, where dozens of critics had gathered to write, I was casually explaining my sense of personal disappointment with The Zone of Interest’s emotional impenetrability to two critic friends—a Korean and an Egyptian—whom I see every few months on the festival circuit. No sooner did I begin dismissing the film than a German, a tall gentleman with curly blond hair and black framed glasses, interrupted me in order to deliver a passionate defense of its quality. Half the room listened to our quarrel.

“I must respectfully disagree with you, as the film shows the way that those who operated the factory for eliminating people can turn off their feelings,” Gregor Wossilus, a journalist for Bavarian Television, declaimed passionately. He loved the fact that The Zone of Interest depicted the family of the Auschwitz commandant living a bucolic life outside the camp’s gates, completely inured to the monstrous suffering taking place a few feet away. He continued, “This film offers a view of the famed German ingenuity and it shows that we can push genocide away. It shows that people can stop thinking whether things are wrong or right in order to pursue their narrow self-interest. It was just work for the people who did this. Look! The Fuehrer gave us this great house!” I had not anticipated that the film would touch such a chord among other viewers, but it clearly had. At the other side of the table, a Chilean journalist interrupted us to say that the story Glazer had told was in fact universal and that the film had reminded her of what had happened when her native country was ruled by a junta for 17 years. A raucous debate among passionate and opinionated film people! This was what Cannes had promised!

The program this year is very strong, with plenty of entries from cinematic heavyweights who have had multiple previous films in competition here. Aside from Scorsese and Todd Haynes, there is the Turkish filmmaker Nuri Bilge Ceylan, whose Once Upon a Time in Anatolia won the Grand Prix in 2011. Ceylan has created excitement again at this year’s edition with his ninth feature, About Dry Grasses, which, like his prize-winning film, is an absurd three-and-a-half hours long.

The Monster, by Hirokazu Kore-eda, is the Japanese filmmaker’s fifth entry in the Cannes competition in the space of a single decade. It is also his best since Shoplifters, which won the Palme d’Or in 2018. The story—typical for Kore-eda in that it depicts a very domestic version of Japan—follows a widowed mother who struggles to raise a gifted son who is being abused by his teacher and begins to act out. She takes on the school system and attempts to have the teacher who hit her boy dismissed. The film than pauses and restarts and proceeds to retell the story of what took place from the standpoint of the harried and noble teacher. The depiction of the friendship between the boy and his best friend is absolutely lovely, and it is likely the reason that so many here have predicted that Kore-eda may become the first Japanese filmmaker since Shōhei Imamura to win the Palme d’Or twice.

However, the returning master of the craft who will very much not be winning a prize this year is my beloved Wes Anderson. Despite my lifelong dream of playing the role of myself in one of his productions, I am about to commit blasphemy. Anderson’s entry here, Asteroid City, a theater production within a film within a film set in the 1950s, is perhaps his weakest movie ever. The delicate balance between artifice and heart that has always underpinned his films is entirely off here. It looks like an Anderson film, but the narrative completely fails to hold together. A shame, since The French Dispatch from two years ago was simply terrific.

My wife is completely flabbergasted when I call her after the screening to relate the fact that much like everyone else, I am deeply disappointed with the new Anderson production. In fact, she is shocked. “We have attended Cannes together for 10 years. Through thick and thin, sickness and health, and through Russian aggression as well as that time when you accidentally left your primary tuxedo in the Boston airport and the other at home in Odessa and so could not attend the red carpet—and I would never have expected to hear anything so sacrilegious in regards to the sacred art of Wes Anderson? How could this be?!”

For the first half of the festival, the weather on the Côte d’Azur has been infelicitous for the timeless Cannes art of dressing up. Until today, it had alternated between light rain and afternoon storms, thus rendering useless the linen summer suits I had brought down with me from Paris. Two of my six pairs of pastel-striped espadrilles have already been ruined by the rain.

In Cannes, even the most outrageous ensembles are acceptable and welcome. Walking home last night after an evening at the somewhat tepid German industry party held at the German pavilion, I had the momentary feeling that I was hallucinating a giant pink carnation. It was quickly moving toward me between the palm trees lining the Croissete. The pink carnation was no dream, however—it was a Russophone Asian woman dressed entirely in a fluffy costume of a massive pink carnation, gossiping with a Franco-Russian socialite of my acquaintance, who was also dressed head-to-toe in pink. I was so stunned by the spectacle, and so relieved that the massive flower was not a figment of my overactive imagination, that I totally forgot to say hello to Nadia.

Desiccated from the nightly after-parties held at the beachside clubs, I wake up every morning to the soft hooting of an owl. He lives in the palm tree outside of the apartment that I have rented here every spring for the last decade. I have often wanted to take him to the movies. Would my owl friend prefer, I wonder, to see the new Michel Gondry or the new Todd Haynes? Perhaps he has very contemporary tastes and would be more comfortable with the more experimental fare of the Acid Festival. The owls that live in the south of France are the only ones in the world that migrate over the sea to Africa, and he likely spends his winters by the side of an oasis in the Sahara. Perhaps he would want me to take him to see an African film? If that is so, he would have a great selection this year, as the festival programs are full of African films. Often these are directed by women.

Banel & Adama, a film from the French-born Senegalese director Ramata-Toulaye Sy about the collision of traditional ways of life and contemporary social mores set in a Senegalese village, is a debut that is a bookie favorite to take the Palme d’Or. The Tunisian director Kaouther Ben Hania also has a fascinating, staged, and what many critics have rightly condemned as slightly manipulative film, Les Filles d’Olfa, which uses the Lars von Trier-inspired technique of blending docu-fiction and staged autofiction. The film observes Tunisian mother Hamrouni discussing her life and failings with her four daughters, two of whom are her real daughters and two played by actresses, after they fled to Syria to join ISIS. It is a fascinating film, but I, having seen a midnight screening, fell asleep toward the end.

Talk of artificial intelligence could be heard everywhere in Cannes this year. Numerous foundations, production companies, and national pavilions are hosting panel discussions. At a miniature conference, “The Power of Possibility: Exploring the Incredible Potential of AI in Film and Technology,” the experts and technology ethicists were as gung-ho on the possibilities of the new technologies as the industry veterans in the audience were skeptical. Both reactions betrayed the remarkable—and totally understandable—anxiety over the potential of new technologies to transform the film business. Half of the panelists openly wondered if the industry will still need actors, directors, or producers three years from now. “It will not even take that long,” an AI company executive informed me. “Even by the end of next year you will be able to forgo using a studio set and props. You will only be able to forgo using my epic world building game engine in your film if you are shooting in a single apartment and it simply costs less. Everything else will be generated by my programmers.”

The Hollywood writers union remains on strike, and the daily industry glossies are packed with worried articles posing questions such as “Is Chat GPT a Scab?” The electronic models have not yet trained to analyze screenplays, but there is nothing to stop a Hollywood studio from designing an algorithm based on their extensive back catalog of classic films. The robots just need to be let loose in the film vault.

“That is one of the main negotiation points in the walkout,” a striking member of the writers guild who attended the conference informed me. “The kinds of films that are premiered here at Cannes will not be replaced by robots, but the formulaic stuff on TV is stuff that can easily be made into a rough draft by a robot, a rough draft that could be rewritten on the cheap by a second-year film student.”

The conference mostly dealt with the visual application of the technologies. The process of digitally de-aging actors, for instance, was about to become much less expensive. Even modifying the movements of an actor’s mouth for the sake of dubbing, or for changing the rating on a film by getting rid of curse words, was also about to become a standard practice for the industry. The application of the technology will be transformative, of that there can be no doubt. But as a dedicated Luddite, I do retain the humanist hope that the robots will never be able to replace some roles—dashing culture-critic dandies running around festival parties in wet espadrilles being one of them.

The Italian waiter serving brunch at the Barthelemy cafe (which refused to turn down the music on a hung-over Saturday morning) confidently informed me that his restaurant makes the greatest shakshuka in all of Cannes. How could such roguish bravado go unchallenged or untested? Yet barely had the eggs arrived when the festival app on my phone lit up with some unexpected news. The ticket distribution system remains entirely botched this year, so I was astounded when it suddenly proffered a leftover ticket for Pedro Almodóvar’s gay cowboy flick Strange Way of Life. The film was set to begin at noon, and I only had around 12 minutes left to devour the eggs, settle the bill, and battle my way through the crowds capering in front of the Festival Palace. But of course, running around like a maniac in the quest for elegance and beauty is par for the course for Cannes.

With 15 seconds left to spare, I lunged through the doors as they were being shuttered. I would not miss the chance to see Pedro Pascal’s exposed posterior after all! Strange Way of Life is now the second English-language production from Cannes habitué Pedro Almodóvar. Years ago, the Spaniard decided to forgo the directing of Brokeback Mountain when they first invented the genre of the gay Western. Yet the itch clearly still needed to be scratched. Shot in Spain in authentic spaghetti western style, the film tells the story of two handsome, middle-aged cowboys—one a retired gunrunner turned town sheriff played by Ethan Hawke, the other a nomadic gunslinging rancher played by Pedro Pascal—who reunite after 25 years. The two men had a legendary tryst in Mexico when they were young, and now the romance has been rekindled over a bottle of wine. Both Hawke and Pascal are clearly having the time of their life hamming it up in this campy and riotously amusing film. The morning after their reunion, we learn through some very forced but still charming dialogue that Pascal’s son has recently shot the wife of Hawke’s dead brother. Hawke—who quite naturally has also engaged in a dalliance with his dead brother’s wife—must arrest his lover’s son for murder. But not if his lover has anything to say about it!

The short film was tremendous fun, and when, at the press conference, Almodóvar mused about turning it into a full-length feature, the press corps went wild. Indeed, it was a rare instance when one wishes that a Cannes film were longer. In the evening after the screening, I would randomly run across Hawke in the lobby of the plush Majestic Hotel, and had a chance to deliver an extemporaneous version of the gratitude that I described in my previous diary entry for Hawke’s support for Ukraine. The New York cowboy, I am pleased to report, was as gracious as ever.

Cowboys and buccaneers are all over the Croisette this year. A dignified African American gentleman in his mid-50s, enveloped in a black suit and a matching black cowboy hat and bolo tie, languidly smoked his cigar outside of the entrance to the Carlton hotel. I wondered if the gent had had a chance to attend the screening of the recently restored 1962 Argentine film Hombre de la esquina rosada (Man on a Pink Corner), director René Múgica’s adaptation of a Jorge Luis Borges tale of gaucho cowboys, revenge, and honor. It is one of the undeniable pleasures of the annual pilgrimage to Cannes to find oneself immersed in the Cannes Classic section, with restored historical films running the gamut from the legendary to the remarkable to the completely obscure.

Yet the grandest cowboy film this year is without a doubt Killers of the Flower Moon, a three-and-a-half-hour-long deconstructionist Western from the 80-year-old Martin Scorsese, who has complained to the press about becoming an old man and running out of time despite having many more stories to tell. Sadly, I must admit that I was forced to forgo my own tickets as the screening interfered with the award ceremony of the European Solidarity Fund for Ukrainian Films. Early this year, the European film community had put together a million-euro relief fund to help Ukrainian filmmakers in the midst of war.

My wife, Ukrainian film producer Regina Maryanovska-Davidzon, was one of the 11 recipients of the solidarity funds for Ukrainian film maker Olya Chernykh’s forthcoming A Picture to Remember, a documentary about the way that the war has displaced her doctor family in Donetsk. Every Cannes cowboy knows that family comes first. Pascal also skipped out on the red carpet premiere in order to attend his sister’s college graduation.

The Ukrainian state has other priorities than film at this moment and the Europeans have stepped in to help. “Forgive my impertinent joke, but it is the least that the Germans could do with Merkel tethering the German economy to Russian gas and Berlin then botching the deterrence against the Russian invasion,” I quipped to a German industry film elite. “That is not even a joke, that is just a statement of empirical facts,” the German replied. Indeed, this year, the Germans wound up quietly paying the fees for the Ukrainian film pavilion out of guilt and “a sense of responsibility.”

Though I was unable to see it this weekend, I can report that Killers of the Flower Moon has garnered mixed emotions and reviews. The British critic John Bleasdale, whose filmic judgments I generally trust, thought Killers of the Flower Moon was too much like a Coen brothers tragicomedy. It is “part Western and part true-crime thriller which never quite finds its groove,” he informed me. “There is a lot to love here—especially in the great and masterful performance by Robert De Niro—but I kept thinking that it would have made a great miniseries, which, given its three-plus-hourslong frame is how people will probably watch it anyway.”

On the other hand, it seems that the ambivalence and perplexity that I had experienced upon viewing Jonathan Glazer’s Zone of Interest was not at all shared by the majority of my colleagues. The critics and hacks haunting the press screenings and clattering away on their laptops in the festival press center all seem to have been floored by the film. Bleasdale told me that “Zone of Interest just grows and grows within me as I think about it. If Cannes this year has another masterpiece like this coming up, we’re in for a vintage edition.” Thus Glazer, a cult favorite filmmaker who makes a beautiful and perfectly cut film every 10 years, has gone from being worshipped by cineastes and film nerds to being a front-runner for a major festival prize this year. Just as the film based on his novel was beginning to cause excitement among the critic set in the Croisette, word arrived that Martin Amis had succumbed to cancer at the age of 73. Despite my personal misgivings about the frosty formality of the film, it would surely be a very fitting way to honor Amis if a film based on his work were to receive festival accolades this year.

Another indicator that Cannes has returned to normalcy—while also having a very odd program—is that one of this year’s most anticipated movies was a formalist Holocaust film based on a Martin Amis novel. Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest, titled after the German bureaucratic nomenclature for the area surrounding Auschwitz, is the latest entry into the recent trend of avant-garde and conceptually experimental Holocaust films.

Zone of Interest is the fourth feature-length production from Glazer, and it was widely expected to be a return to form for the British auteur, who has spent nearly a decade away from the film festivals. Glazer’s last film was a minimalist science fiction serial-killer thriller set in Scotland, and here the filmmaker’s surgical aesthetic remains the same. The movie is based on the real-life exploits of the SS Commandant Rudolf Hess, a Nazi apparatchik who managed Auschwitz with rigorous efficiency and was responsible for many of the technological “innovations” that were formulated there. Glazer, an uncompromising aesthete, was utterly scrupulous about the recreation of the Nazi household at the center of the film—the flower patches in the garden were reportedly placed in their exactly correct historical locations.

The film does not actually show what took place in Auschwitz. Instead, it is almost entirely set in the family home that the commandant shares with his wife and their five model Nazi children in a house directly outside the gates of the camp. Most of the more gripping parts of the film consist of long and tedious bureaucratic meetings, in which the attendees discuss the most horrific matters in the most bland way possible. A scene with dozens of senior SS generals gathered together to discuss implementation of the Holocaust literally concludes with the reading out of five subheader themes for transportation logistics. The film does not represent a particularly literal adaptation of the Martin Amis 2014 novel, which, when I read it a decade ago, struck me as one of his weakest. Schindler’s List this certainly is not.

The Hess character is not just an anodyne overrepresentation of the “banality of evil”—he is actually fairly effete, as well as dull. The conversations between him and his wife could not be more insufferable, with their spiritual concerns mostly having to do with housing needs. (Were the Nazi administrators actually just striving German bourgeoise?) We hear about the commandant’s normie patriotism while his Hausfrau wife spends her days gardening and manicuring the yard, even as muffled screams and shots can be heard in the distance while the sky fills up with plumes of crematorium smoke. Auschwitz is on the other side of the wall, and the tonally and emotionally planar film offers us glimpses of trains arriving and military trucks being unloaded, yet the audience is kept at the same emotional distance from what is happening as the family is.

The cinematography is indeed scrupulous. This was “devastating Holocaust drama like no other, which demonstrates with startling effectiveness the British formalist’s unerring control of tonal and visual storytelling,” according to the Hollywood Reporter‘s chief critic. “Working with Polish cinematographer Łukasz Żal, who shot Pawel Pawlikowski’s beautiful black-and-white companion pieces Ida and Cold War, Glazer embedded remotely operated cameras in production designer Chris Oddy’s reconstruction of the Hess residence. They shot simultaneously on up to 10 cameras in different rooms using no film lights and allowing the actors to move unobstructed.” Many critics have referred to it as “spare” and “bone-chilling”—but I found it merely cold, occasionally shading into the evocatively bland.

I must confess: I found it exceedingly difficult to know what to make of The Zone of Interest as a work of art. It certainly does not deliver the visceral blow or moral arguments that one expects from any film dealing with the Holocaust. The Jewish French film critic that I watched the film with (“Vlad, under no circumstances am I to ever see my name mentioned in the American press!”) was as baffled as I was. “I am left feeling divided and perplexed having watched this,” he informed me, “and I do not know how long it will take me to figure out what it is that I have just seen. I also do not envy you the task of having to write about something so opaque immediately after having seen it,” he told me. Indeed, I wasn’t sure, after I had left the theater, if I was deeply numbed or merely unmoved.

It turned out that this year’s most coveted—and impossible to attain—ticket was not for the new Indiana Jones sequel or the new Martin Scorsese flick. It was for Pedro Almodóvar’s 31-minute-long, queer-themed Western Strange Way of Life. On the rain-drenched second day of the festival, a huge crowd materialized in the standby line with vain hopes of procuring a ticket. This was in many ways totally understandable. Who among us would not want to watch a gay cowboy flick starring Ethan Hawke and Pedro Pascal? In fact, Almodóvar showed truly admirable restraint in not making the film nine minutes longer, thereby qualifying it to take part in this year’s official competition as a stand-alone feature. My informant, who miraculously got into the screening, informed me that Pascal bares his firm backside. As a fan of Almodóvar, Westerns, and Ethan Hawke, I would dearly loved to have seen it.

I also want to state unequivocally and for the record that Hawke is a real mensch and a total sweetheart. Last April—that is, two months after the Russians first invaded Ukraine and began trying to kill my friends and family—we were all running around raising funds and acquiring equipment for the Ukrainian army. At that time, the courtly and affable Hawke attended a speech that I had delivered at a fundraiser in New York City. After I spoke, Hawke approached me with kind words about my speech and politely asked me to autograph his copy of From Odessa With Love, my book of essays on Ukrainian politics. God bless you, Mr. Hawke!

Ukraine, to our great relief, still seems to be on the minds of many of the attendees and its friends. It being Vyshyvanka Day—named after the long-sleeved shirt of the Ukrainian national costume—the American pavilion hosted a midday panel on the future of the Ukrainian film industry, which gathered together a group of Ukrainian film world leaders as well as the American actor and producer Billy Smith. The avuncular Smith, a close confidant of Sean Penn, was in town to discuss Superpower, the documentary on the Ukraine war and President Zelensky that Sean Penn had co-directed with American filmmaker and producer Aaron Kaufman. Smith had produced the film and joined his friend on the frontlines in eastern Ukraine. (Full disclosure: I worked on the film as an associate producer and am featured as a talking head in the film. I also interpreted some of Penn’s meeting with Ukrainians at the start of the war and brought him to see the Polish prime minister.)

Superpower had its world premiere at the Berlin Film Festival and should be widely distributed shortly. Smith, who is known for his collaboration with Scorsese in The Irishman, also played the role of a Boston cop in The Departed—a role that the blue-eyed Irish American had once played in real life as a young man, before he became involved in acting through the American Repertory Theater. Smith is likewise a real mensch. On the panel in the American pavilion, he recounted the story of how Penn had first met President Zelensky on the night before the war had begun, as well as the remarkable manner in which the Ukrainian president had kept his promise to allow Penn and Kaufman to begin shooting interviews with him on the morning of Feb. 24. Zelensky kept that promise even as the Russians began rolling their tanks into Kyiv.

Over at the Ukrainian pavilion, the young Ukrainian cineastes gathered to toast Vyshyvanka Day as well as to look for international support for Ukrainian cinema. The Ukrainian filmmaker and scriptwriter Tonia Noyabrova, a very lovely and charming friend of mine who hails from a long line of Ukrainian Jewish actors, ran up to hug me. I almost spilled my Ukrainian white wine, brought for the occasion, onto her elegant floral print blouse. I had last seen Noyabrova in February at the after-party for the Berlin Film Festival premiere of her poetic coming-of-age film Do You Love Me, which is set on New Year’s Eve 1991, as the Soviet Union is about to dissolve. Noyabrova and her crew had just completed shooting in Kyiv a week before the Russian invasion began. I play a brief cameo in the film as “Drunken Intellectual #2.”

Noyabrova informed me that she was slightly miffed that she had not gotten a chance to attend the gay cowboy Western. To cheer her up, I theorized that perhaps only members of the gay cowboy community had gotten a chance to attend the screening. Still, she was thrilled with the reception that Do You Love Me had received in Berlin. “We are currently in the midst of negotiations with HBO Europe, who are interested in buying the movie,” she informed me. She was also excited about her next project, a “very sarcastic and ironic” drama about Ukrainian refugees who are stuck in Western Europe and are desperate to return to their Ukrainian hometown after it is occupied by Russians.

Soon, Andrei Lenart, an improbably handsome, square-jawed, and impeccably blond Slovenian actor with a very droll sense of humor, struck up a conversation with me. Lenart had come to the Ukrainian pavilion to show his solidarity with fellow post-communist Eastern Europeans. The Slovenian gentleman had just completed work on a new adaptation of a Tom Clancy novel in which he had been typecast. “Did they cast you as a Russian terrorist?” I inquired. “No, I was a Russian naval officer,” he responded in his flat Mitteleuropäisch accent. I was forced to inform him that the two roles were considered to be much the same thing in the Ukrainian pavilion.

Lenart did indeed look like a dashing Ubermensch straight out of central casting, and he entertained no illusions about being continuously cast as a villain. “Look, I understand the way that the industry works, and so I do understand that every time I have an audition it will be either for the part of a Nazi officer or a Russian naval officer. I have leaned into that and will have to make the most out of it,” he told me. At home, in Slovenian productions, he had gotten used to playing the hero: “Every Slovenian mother wants me to be her son-in-law!” Sadly for my amusing new acquaintance, his home country only produces around half a dozen films a year. The world being what it is, he will surely have to get comfortable with playing Russian bad guys for the foreseeable future.

The vulgarities and pleasures of the festival are manifold. Cannes is a medium-size town, and when the international film circus arrives, it takes the whole place over, bringing a churning, frenzied, and near-violent edge to an otherwise placid and elegant beachside city. This doesn’t happen with other A-list film festivals, like Berlin, Venice, and Toronto. The Venice Film Festival is hermetically sealed in a small territory around the Hotel Excelsior (which I was married in) and effectively closed off to anyone outside the film industry. Toronto is far too Canadian to be sexy. The Berlin Film Festival is grand, but it’s ultimately just another big event in the midst of the bustling German capital.

In Cannes, however, hedonists, nouveau riche Eurotrash, and professional party people from all over Europe come for the brazen night life. One meets all sorts of characters here who have no discernible business at the festival—people who never set foot inside a producers’ meeting, an industry gala, or even a movie theater but who spend their evenings at the parties in the luscious villas tucked into the hills above the Cannes harbor. These parties run the gamut from the very officious to the very scandalous, although, having failed for the 10th straight year to secure an invite to the legendary party thrown by Leonardo DiCaprio, I know that I personally have yet to experience the peak of festival debauchery. So while there are moments of real tenderness and grace here, and authentic elegance of spirit, Cannes is at its heart indescribably sleazy.

Ultimately, we can all watch the films by ourselves at home. We come to Cannes to socialize. Flitting about between the movie theaters, nightclubs, cafes, and industry events held in the national pavilions or beach clubs, one is liable to run into characters that one has not seen in years. Every critic, writer, filmmaker, and producer has festival friends—the individuals that one drinks, parties, and argues with exclusively on the festival circuit. At the end of my first night here, I find myself at the table of various old comrades.

Half a dozen people opine on the quality of the Johnny Depp performance in the opening night film. We listen to a Franco American woman in her 30s loudly discuss her Botox routine with a pair of male German distributors. The Germans nod gravely. At the next table, a Jewish guy with a Bensonhurst accent of the kind I haven’t heard in two decades is kibitzing with his colleague from LA. “So, you getting out of the film business for good?” the New Yorker asks his colleague skeptically. “No one ever leaves the film business for good,” his friend responds.

There goes the quirky Korean photographer one sees around Paris. In civilian times he takes society party photos at the Cafe de Flore in Paris. There is the German film distributor who one time gallantly shared his cocaine in the bathroom of a Berlin night club at a Berlinale Festival. There is a portly Russian oligarch drinking champagne alone at a table in the Majestic Hotel. Two summers ago, he paid everyone’s bar bill. Now he’s on the U.S. Treasury Department sanctions list. Do you really want to be seen in public with him this year?

Speaking of Russian producers who have found themselves in trouble—the first day of the festival brought news that Moscow had issued an arrest warrant for Kyiv-born and Oscar-nominated Russian American film producer Alexander Rodnyansky. The gentleman spends a large portion of his time in Los Angeles and will presumably not be stepping foot in Russia for the foreseeable future. The Russian court is also prosecuting the renowned theater director and playwright Ivan Vyrypaev for the newly created crime of “spreading false information” in regards to the Russian military. Rodnyansky, whom I interviewed for Tablet in February as part of the Kyiv Jewish Forum, has been one of the most prominent figures in film production in Russia, but as a Ukrainian-born Jew he has stridently opposed the Russian war against his native country. The AP reported that “according to the court’s press service, Rodnyansky and Vyrypaev, who are outside Russia, will be arrested once Russian authorities manage to detain them or to get them extradited. Russia’s Interior Ministry additionally put Vyrypaev on the federal wanted list.”

After we learned of the Russian persecution of the producer, my friend, the American producer Graham Sack, who works with Rodnyansky, denounced the judicial overreach while we shared our first glass of Chablis at a restaurant fittingly called La Boheme.

“It’s an honor collaborating with Alexander,” Sack told me. “He is a rare breed of producer who is morally and aesthetically driven. He has an interest in moral complexity that strikes me as being not only inextricable from his aesthetic taste and political dissidence—complexity being the antipode of propaganda—but also Jewish in its sensibility, complexity being the end product of a culture that prioritizes questioning, debate, and pluralism over authoritarianism.”

A veteran attendee of the Cannes Film Festival, dear reader, has every reason to be weary. I certainly am. Like so many of us, the world’s most prestigious film festival has had a run of difficult years. In fact, the last half-decade has been brutal for a festival renowned for its ostensible aversion to politics.

Cannes was indelibly connected to both the filmic exploits and monstrous predations of Harvey Weinstein. The festival was thus in many ways the symbolic birthplace of the #MeToo movement and the interminable culture war that followed. The consequences of that moment would rack the next two iterations of the festival, and that was before the COVID-19 pandemic forced the total cancellation of the 2020 version. The previous time that had happened, Nazi officers were still occupying tables at the Paris Ritz.

The 2021 edition of the festival would be pushed back to the summer—and with Cannes at the vanguard of rigorous and intrusive COVID measures. Asian and North American passport holders were still banned from entering France at that time, and so almost no one came. Those of us that did make the pilgrimage were forced to take a humiliating and near daily, saliva-based COVID test that often provided false positives after a night of excessive drinking, which—let’s be honest—is most nights for most attendees. Still, the film selection was excellent that year, and cineastes with an antisocial streak will recall it as a glorious time to watch films unmolested by the usual crowds, if they could get past the endless litany of jokes about a “feast in the time of plague.”

Last year, the festival opened two months into the unprovoked Russian invasion of Ukraine. Europe was still reeling from the shock of the most merciless war on the continent since 1945—a kind of war that Europe was never supposed to experience again. At the time, the Russians had just been defeated at the battle of Kyiv and had retreated from their positions along the Ukrainian–Belarusian border, while the Ukrainians had begun excavating bodies from the mass graves they had discovered in the recaptured territories. The war posed tremendous political and moral problems for the stridently apolitical Cannes: Russian films were picketed by protesters while the Russians themselves were summarily banned from participation in civilized social life at the festival—that is, being invited to the good parties and being able to partake in international film co-productions.

Last year my Ukrainian friends and I waved the blue and yellow flag after the red carpet premieres. To the chagrin of the festival organizers, we also sang the Ukrainian national anthem inside the Festival Palace after the premiere of Maksym Nakanechny’s Butterfly Vision. When French fighter jets made their acrobatic flybys to advertise the new Top Gun, half the Ukrainian film industry—mostly women, as military age males are still not allowed to travel out of the country—had PTSD flashbacks to the Russian bombing of Kyiv. (The decision to allow those aerial maneuvers over the Croisette, the main beachfront boulevard lined by elegant hotels and restaurants, was a fairly gauche one from the organizers of the festival.)

A year later, the war grinds on, and with the Ukrainian film industry mostly shuttered, the Ukrainians are not represented by a single film in any of the three main competitions. During opening night, legendary French actress Catherine Deneuve recited the poetry of the Ukrainian national poet Lesya Ukrainka. Yet I worry whether any of last year’s solidarity and civil disobedience will actually make an appearance this year.

Still, hopes are high, and matters seem to be less grim than they were this time last year. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky arrived in Paris two nights before the opening festivities for a long dinner with President Macron. He was there to secure the final shipments of French weaponry needed to ensure the success of Kyiv’s forthcoming counteroffensive. On Tuesday morning, under a picture of President Macron grasping Zelensky’s shoulder at the Élysée Palace, Le Monde announced that “Sur la Croisette, un regain de confiance.” The Croisette was back in business, baby!

“The American studios have returned, the first films are encouraging, the sanitary rules have been repealed—and so the 76th edition of the Film Festival promises to bring back optimism to a sector that sorely needs it,” the premier French daily predicted happily. Five years of scandal, plague, and war could not be willed away, but the business of the film business is supposed to be glamour, filthy desire, and escapism.

Yet if the French seem to have had enough unpleasantness, American-style culture war both did and did not seem to be abating. The opening night film Jeanne du Barry, by director Maïwenn, has Johnny Depp portraying French King Louis XV. For the first time since winning a libel trial against his former wife, Depp appeared on the red carpet wearing a double-breasted, half-frock tuxedo with no bow tie. His appearance at the festival had been roundly condemned. An open letter published last week by the French actress Adele Haenel, which accused the festival of “celebrating rapists,” stood in the way of a return to 18th-century-style perfumed decadence and misbehavior.

“People use Cannes to talk about certain issues and it’s normal because we give them a platform,” festival Director Thierry Fremaux said in his pre-festival press conference, in response to the chorus of criticism. “But if you thought that it’s a festivals for rapists, you wouldn’t be here listening to me, you would not be complaining that you can’t get tickets to get into screenings.” (The ticket system was indeed terminally broken as of press time.)

Indeed, Fremaux was refreshingly defiant, and his remarks should serve as a reminder to his American counterparts about the virtues of showing a spine. Variety reported him saying, “I don’t know about the image of Johnny Depp in the U.S. To tell you the truth, in my life, I only have one rule, it’s the freedom of thinking, and the freedom of speech and acting within a legal framework. If Johnny Depp had been banned from acting in a film, or the film was banned, we wouldn’t be here talking about it.”

Vladislav Davidzon is Tablet’s European culture correspondent and a Ukrainian-American writer, translator, and critic. He is the Chief Editor of The Odessa Review and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Atlantic Council. He was born in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, and lives in Paris.