Einstein, Toni, and Me

How I came to know one of the scientist’s love interests from the early days of the Weimar Republic

I might as well confess at the outset that I never actually knew Albert Einstein in person, but as a physicist I have venerated him and his achievements since my student days. I got to know him not only as scientist and public figure, but also as private individual and family man, in the course of my extensive research for two books, one based on Einstein’s candid travel diaries titled (with apologies to Jack Kerouac) Einstein on the Road; and the other, based on the reminiscences of Herta Schiefelbein, the astutely observant housekeeper who lived with the Einstein family for six years in Berlin, titled Einstein at Home. Along the way, I encountered many true Einstein vignettes, some too inconsequential to find their way into biographies, but in toto, most revealing of that remarkable man’s personality. However, there exists a more personal link between Einstein and me: He and I knew and admired the same woman.

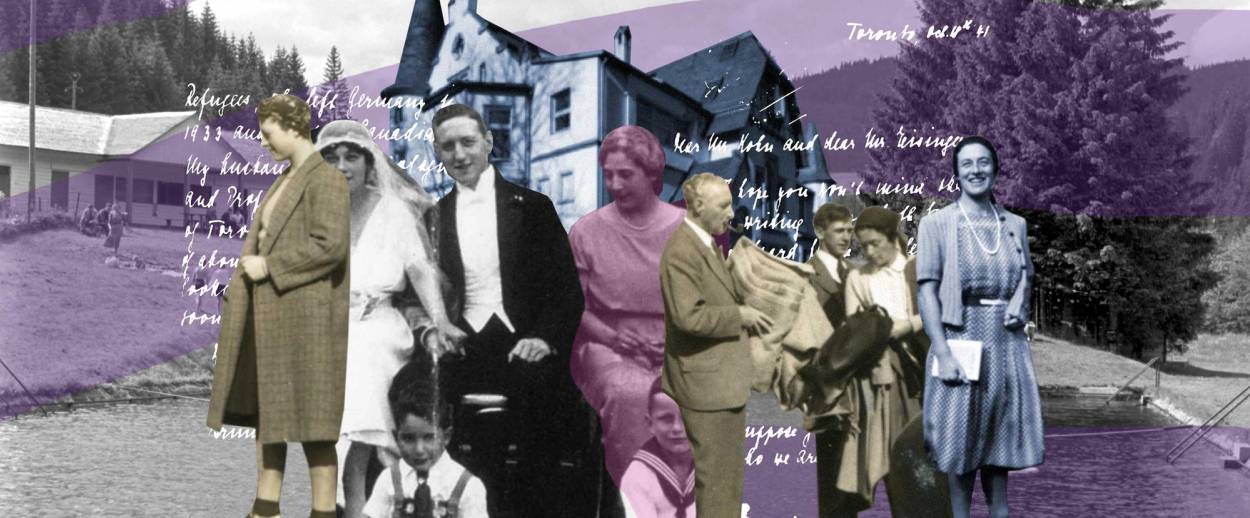

Her name was Toni Mendel, née Antonie Meyer, and she first met the newly famous Einstein in the early days of the Weimar Republic, Germany’s valiant attempt at democracy (1918-1933). At the time, she was married to the prosperous clothing manufacturer Albert Mendel and both the Einstein and the Mendel families belonged to the same pacifist association Bund Neues Vaterland. Her husband died soon afterwards and Toni, as she liked to be called, became a wealthy, thoroughly emancipated widow who relished her independence and traveled by herself in Nubia, now a part of Sudan, at a time when few women ventured to do so. She became a frequent companion of Einstein, who believed that most men (and not a few women) are not naturally disposed towards monogamy. Their close friendship was only very reluctantly tolerated by Einstein’s wife, Elsa, and the two families often visited each other. As Fräulein Herta, the housekeeper, put it: Herr Professor always had a weakness for lovely ladies, adding: On the other hand, beautiful women also liked to be seen with Herr Professor, Toni Mendel among them.

Einstein and Toni often went sailing together, together they read and discussed the latest publications of Proust and of Freud. Her chauffeured limousine picked him up at home when they attended concerts or a play together. When Hitler came to power, both emigrated—he to Princeton, she to Canada—but they continued to correspond with each other. Toni died in 1956, a year after Einstein, and when her daughter Hertha Mendel—of whom more later—came across Einstein’s letters, she looked at a few, exclaimed: “much too personal!” and burned them all—thereby fulfilling Einstein’s own request to Toni’s executors.

I knew Toni—then known to me as Omama (grandma) Toni—some 20 years after Einstein, when she was a lively, elegant, and handsome woman in her late 60s, while I was 19 and an undergraduate student at the University of Toronto. The Second World War was in its third year and I lived with the family of Toni’s daughter Hertha, her husband, Bruno (who was also Toni’s nephew), and their three children in their Toronto home at 98 Bedford Road. In pre-Hitler Berlin, they had all lived together with Toni in her magnificent villa on the Wannsee, whose interior had been designed by Walter Gropius. Gerald, the oldest of the Mendel children, told me many years later of being woken up as a boy to the sound of Einstein’s piano playing, after spending the night at the villa. Bruno Mendel was a medical researcher and he had built a private laboratory on the villa’s grounds, where Einstein liked to visit and to offer technical advice pertaining to Bruno’s experiments while sitting on a lab stool.

The curious circumstances that led up to my quasi-membership in the Mendel family clearly call for an explanation. A year after Hitler’s occupation of Austria (1938), I made my escape from my native Vienna to England on a Kindertransport, albeit without having a sponsor, as was normally required. Avoiding deportation, I worked, first, as a farm hand in Yorkshire, and then, as a dishwasher in a hotel in Brighton when, in the wake of the Dunkirk evacuation and the fall of France, England was gripped by justifiable fears of an imminent German invasion. Churchill ordered—in his inimitable phrasing “Collar the lot!”—the internment of all enemy aliens (i.e., those with German passports) who resided within 50 miles of the coast. Since no attempt was made to differentiate between Jewish refugees and possible Nazi agents, I was arrested and was among the few thousand internees, who, a few months later, were shipped to internment camps in Canada—for safekeeping, “for the duration.”

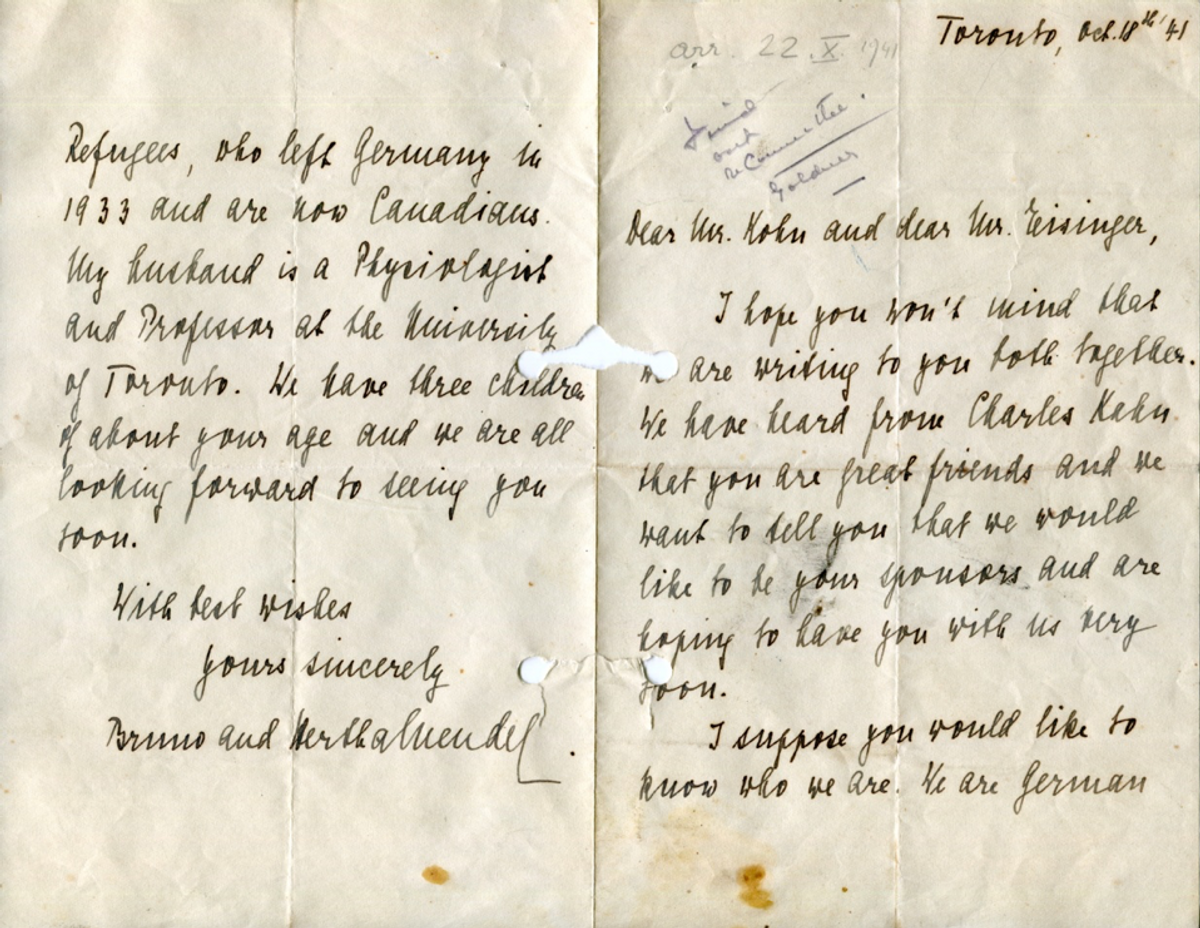

It took about a year before the Canadian authorities saw the folly of keeping fervent anti-Nazis locked up while fighting a war against the Nazis, and they permitted bona fide students to be released if their support was guaranteed by a Canadian sponsor. As luck would have it, the Mendel family generously provided the necessary guarantees for me and my friend Walter Kohn, and invited us, moreover, to live with them in their Toronto home—knowing no more about us two, than that, in the camp, we had played recorder duets together. Needless to say, Walter and I found our Shangri-La in the Mendels’ home and we soon adapted our Viennese ears and palates to our hosts’ North German speech and cooking. After having been confined in camps for almost two years, we relished the warmth and the cultured, intellectual ambiance of the household and instantly felt at home there. We helped the Mendels’ daughters, Ruth and Anita, with their homework, while Gerald gave us driving lessons in Bruno’s Oldsmobile car. After passing the matriculation exam, I enrolled in the mathematics and physics honors course at the university and after a stint in the Canadian Army, I finished my studies after the war. Though I no longer lived with the Mendels, we remained close friends. A few years after the war, Bruno and Hertha moved back to their beloved Holland, not before presenting to my wife and me two striking chandeliers and other furnishings that had once graced their Wannsee villa. I visited them whenever I was in Europe; but the three Mendel children, as well as their Omama Toni, remained in Canada.

During the half-dozen years that I knew her, Toni lived in Oakville, a suburb of Toronto, on the shore of Lake Ontario. That site may well have reminded her of the second home she used to own which was located on the Zürcher Lake in Switzerland. It had afforded Toni and Hertha’s family their first refuge from Hitler’s Germany. Toni and her family had been politically astute enough to recognize very early the looming danger posed by the Nazis, and Toni had, indeed, sold her Wannsee property and left Germany a year before Hitler became chancellor in 1933. As a result, she had been able to leave with her considerable fortune intact, which sustained her and her extended family in the years to come. Ten years later, it helped to sustain me, too.

I saw Toni on her occasional visits to Hertha’s family on Bedford Road, but more often, I visited her at her Oakville home, which I could reach on my bicycle. Because the Mendels left Germany so early, they were able to bring with them some of the art work, books, and furniture of their Wannsee home, with the result that both Toni’s Oakville apartment and the Mendels’ Toronto home preserved the ambiance of their Berlin abode. Of my visits for tea with Toni I particularly recall her eagerness to learn of the latest developments in the arts, in science, in politics, and how I viewed the progress of the war. Her wide-ranging curiosity must also have intrigued Einstein, whose interests ranged far beyond physics. He was, for example, deeply devoted to music and he played chamber music whenever he could, often three times a week. In the Berlin days, Einstein was, moreover, actively engaged in the tumultuous politics of the Weimar period, and at the same time, he was intensely involved in the design and production of gyrocompasses, engineering work for which he was awarded several patents.

Einstein believed strongly that science ought not to be reserved only for academics. After he completed work on the general theory of relativity, one of humanity’s greatest intellectual achievements, he gave his first lecture on it, not to fellow scientists, but to a lay public audience at the Treptow (now, Archenhold) Observatory in Berlin, in 1915. Later, again, he addressed 300 workers and unemployed persons in a school auditorium in Berlin on the topic, “What the Working Man Must Know About the Theory of Relativity.” In 1930, when radio was a great novelty, Einstein spoke at the opening of a broadcasting exhibition and reminded his audience, “present and absent,” of the scientists who had made radio a reality (naming Oersted, Bell, Maxwell, and Hertz). He admonished his listeners not to consume the wonders science has made possible with as little intellectual curiosity as a cow, chewing grass, has in botany.

Toni may well have been more than a sailing and intellectual companion of Einstein, and the pair must have enjoyed each other’s company, for both had a sense of fun. Among Einstein’s lesser-known characteristics is that he loved to laugh and that a joke or a comical situation of any kind was liable to provoke him to irrepressible mirth. Once, while traveling by train in England, the train passed through an industrial town with many smokestacks, and Einstein’s travel companion commented to him that the town was “das englische Essen”—the city of Essen being an important German industrial center, as well as meaning “food” in German. Einstein’s thoughts were evidently elsewhere and he responded with: “Yes, it is ghastly. They cook everything with mutton fat.” This linguistic misunderstanding cracked up the two travelers, and each time Einstein related it, he again went into a spasm of laughter. He reacted in much the same way when Herta Schiefelbein, the Einsteins’ housekeeper, accidentally propelled the strawberry cake off the veranda table while trying to shoo away a bee.

Toni had enjoyed the high-spirited independence that Einstein probably admired—if not envied, for he never ceased being at heart a bohemian who disliked socks and loathed all formal attire. Toni’s mettle is evident in the doggerel poem that she composed on the occasion of her 50th birthday, which occurred in 1928. Here it is, freely translated:

I: Frau Mendel: who e’en today

Will be 50 years of age—

No matter! Slender am I, like erstwhile Juno,

Bend one and all to my will—excepting Bruno.

Apart for him—count on that,

I am not scared of anyone.

To be a meek hausfrau, I don’t pretend,

That I tell you straight to your face.

Let others bake, let others mend

That sort of thing I don’t embrace.

Wildly to rule, is what my spirit loves,

Unless I happen to be on a trip.

And in my constant quest for wisdom

I never let my diligence slip.

I am a true philosopher,

That’s why to Einstein I pay court

And buy him everything in sight

That an old sinner will delight.

But the best thing that I know,

(To Hertha, too, it gives great joy)

Is chewing through bold building plans

Alongside an expert in my employ.

To build new houses, old ones to restore,

Nothing could ever please me more!

To reach a conclusion today,

And in the morning discard it,

Nothing delights me more, I say,

How glorious it is to live this way,

Can anything be better?

Wake up, all ye philistines, and see

How it’s done by Toni, me!

This (translated) fragment of a 1927 letter that Toni wrote to her family on her way home from Africa, reveals another side of Toni:

The last two days were for me the loveliest of the entire trip because the austere beauty of Nubia has totally conquered my heart. It is just like with an austere person: It takes a long time before love is awoken, but then love is strong and forever. I am quite ecstatic, to have made this strange country a part of me forevermore, and I even hope to come back. It seems miraculous to me, that instead of being homesick, I long for Nubia. All the same, I am glad to be traveling northward.

In the wake of the calamitous First World War, many German intellectuals cultivated an interest in Eastern philosophy and religion. Toni and her daughter’s family were among them and they became closely acquainted with the Bengalese poet, artist, and musician, Rabindranath Tagore. Bruno Mendel even arranged two meetings between Tagore and Einstein. One of these took place in Toni’s Wannsee villa, and the recorded dialogues of the two men were followed with great interest, for they were widely seen as representatives of the Eastern and Western philosophies of life.

In 1953 when everyone was enthralled by the televised McCarthy hearings, Einstein, now an American citizen, took a widely reported public stand against the House Un-American Activities Committee. Toni wrote him a congratulatory letter and in his reply Einstein said he was glad to see that the “old fire was still crackling fiercely in [her] breast” and that her letter had reminded him of the time when they were on the warpath together in post-WWI Berlin.

It was at about that time that I visited Toni in Oakville for the last time. She was in an unusually pensive mood and said that it made her sad that all of one’s accumulated knowledge and understanding of the world was lost when a person dies. Just before I said goodbye, Toni asked me if I knew of any laws of physics that would preclude the transmigration of the soul after death. I assured her that I knew of none and she seemed relieved.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Josef Eisinger, professor emeritus in the Department of Structural and Chemical Biology at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York, is the author ofEinstein on the Road andEinstein at Home.