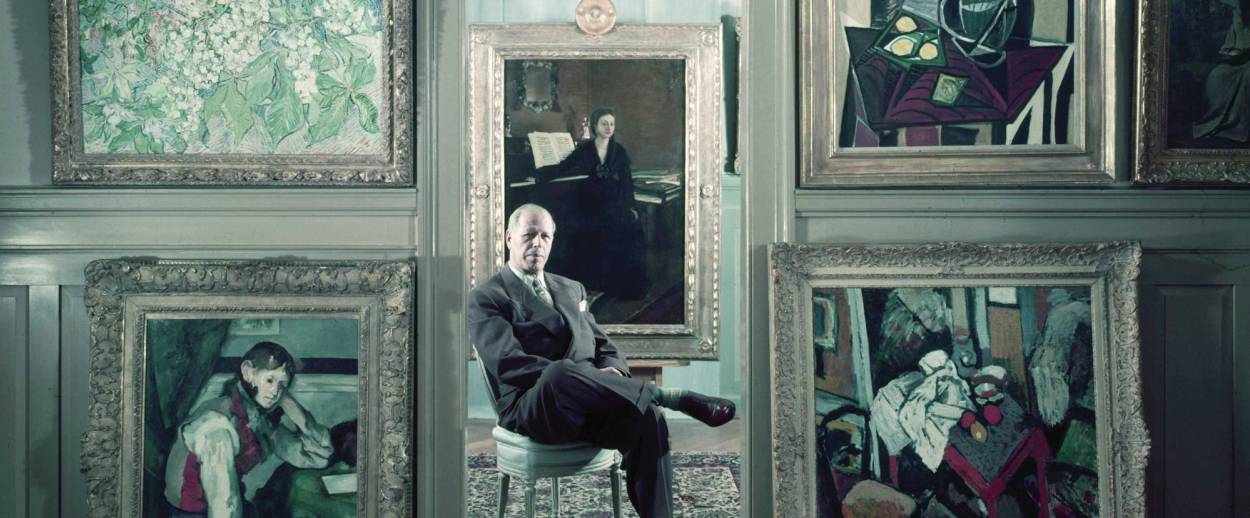

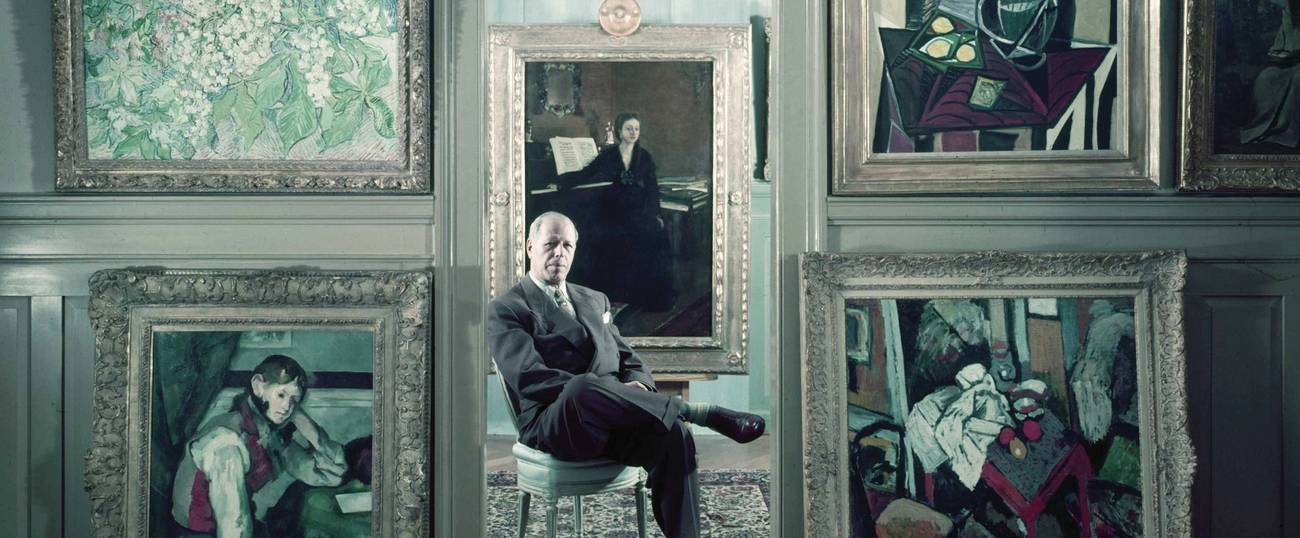

Mademoiselle’s pale eyes are flecked silver and blue, gazing with such melancholy that the delicate girl in a Renoir portrait seems to foretell her own family tragedy. Yet most visitors study the 1880 “Portrait of Mademoiselle Irène Cahen d’Anvers” with no clue as to the dark history of the painting that was plundered and turned into a trading chip during the German occupation of France during World War II. The painting is part of a new exhibition of the collection of Emil Bührle at the Musée Maillol in Paris through July that features about 50 works by Renoir, Degas, and Manet that were partly amassed by the German arms manufacturer during a period in which he dealt weapons and art to the Nazis.

“La Petite Irène,” which once hung in the grand Parisian mansions of Irene’s Sephardic art-collecting relatives, was looted in July 1941 by German forces from the Chambord chateau in the Loire Valley where various Jewish collectors sent precious works for safekeeping alongside the Louvre’s state-owned collection. Irène’s son-in-law, Léon Reinach—convinced that the family of bankers was secure because relatives and in-laws had donated so many precious art works and properties to France—demanded its return. In German documents, Reinach’s demand drew attention to the family and he was dismissed as an “insolent and pretentious” Jew. Months later, he and Irène’s daughter, Beatrice, and their two grown children were deported to Drancy and then to Auschwitz. Irène’s sister, sheltered by her housemaid and her chauffeur, was deported later in 1944.

Most museums gloss over these inconvenient facts of looting, like cracks in a vibrant painting. Information is revealed in minimal terms and the voices of victims and their descendants are rarely heard. There are emerging signs of a cautious movement among curators to be more “transparent,” but there is often missing information that gives reality a vague, impressionist quality.

Earlier last year, the Louvre opened a small gallery devoted to unclaimed looted art. Yet the museum, the most visited in the world, offers no information about the last known original owners, the provenance, or the individual stories of the disappearance of the works.

A special website, named for Rose Valland—a museum administrator and French resister who secretly spied on German authorities at the Jeu de Paume distribution point in Paris for the collection of spoils—does offer a list of more than 2,000 unclaimed works of art from the war held in trust by French museums. But the information is limited and marred by errors and misspellings of family names. It is awaiting a makeover—part of a fresh attempt to tackle the issue of looted art by the French state, which is restructuring a unit of five people within the Ministry of Culture to work aggressively to seek out the rightful owners or heirs of artworks plundered or sold under duress.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Portrait of Mademoiselle Irène Cahen d’Anvers, 1880. (E.G. Bührle Collection)

To its credit, the Musée Maillol in Paris and the Bührle foundation devoted a special exhibition section with some information about the 13 looted works that Bührle acquired during the war and later restituted and then purchased back from the original owners. But the whitewashing of Bührle’s wartime role continues. After the Paris opening in March, I overheard a guide explain that Bührle acquired the works in “good faith.” She faulted unscrupulous Parisian art dealers during that booming period under the occupation when the art market became a complex circuit of stolen works, driven by confiscations and the peculiarities of Nazi taste.

The guide was merely echoing the text that the Musée Maillol had placed by posters of looted works by Pissarro, Degas, and Manet that surfaced in Bührle’s collection. Swiss authorities, according to the museum’s brief account, ordered restitution in 1948 “even when the works had been acquired in good faith.” On another day, a different guide repeated the same point, adding that the arms dealer was “friendly” with one of the victims—Jewish gallery owner Paul Rosenberg—whose looted works he acquired.

The explanation seemed odd for a museum that less than two years ago hosted an exhibition about Paul Rosenberg. The facts are that this gallery owner actually demanded restitution of a Matisse from Bührle, who refused, telling him he thought he was dead. The owner sued Bührle and others in Swiss court to recover his stolen paintings whose frames were stamped with his name by the Nazis.

Bührle was no naïf in the view of investigators for the Allies, who considered him the leading buyer of looted art in Switzerland. He purchased paintings in Paris through intermediaries for Adolf Hitler’s second-in-command, Hermann Goering, and in turn he provided Goering with coveted Swiss currency, according to Emmanuelle Polack, the curator of a new exhibition at the Memorial de la Shoah in Paris that takes a critical look at the art market under the occupation. It includes a photograph of Louvre officials gesturing a Hitler salute to a high Nazi official.

“La Petite Irène” was plundered from the Chambord castle on orders of Goering, an obsessive collector who was not a fan of Renoir because Nazis considered his impressionist style degenerate. But he still used the valuable art for trading: Goering swapped the portrait in 1942 for a Florentine Tondo with a Paris gallery dealer who was one of his chief art procurers. Some historians contend that the painting was then bought by another Swiss gallery owner who held it along with others for Bührle because of the growing risks of buying plundered art.

After the war, the portrait ended up in a 1945 Munich collection point for spoils of war and then at a 1946 exhibition of plundered masterpieces at l’Orangerie in Paris. It was there that Irène Cahen d’Anvers spotted the tender version of herself, a work that she hunted for after the war, calling it a delightful memory of her youth. She had survived the occupation, cloistered in her Parisian apartment. Years earlier she had scandalized her family by converting to Catholicism and deserting her husband, the Count Moïse de Camondo, to marry an Italian aristocrat with a name change to Sampieri, which seemed to protect her in those turbulent times.

The countess lived on into her 90s in her Cannes villa in the south of France, inheriting the fortune of her daughter, Beatrice, who died in Auschwitz. Through her life, she resolutely struck the same Renoir pose of the girl with a blue ribbon—head tilted left. She sold her portrait to a Swiss dealer sometime in the 1940s; it was then purchased in 1949 by Bührle. A friend said the countess avoided discussing the tragedy of her murdered daughter and grandchildren. She left it to her portrait to bear witness to the powerful memories of suffering and mourning—a history that is always on exhibit.

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Doreen Carvajal is a former reporter at the New York Times and co-founder of the Orphan Art Project, which aids descendants seeking restitution of looted art and recovery of family history.