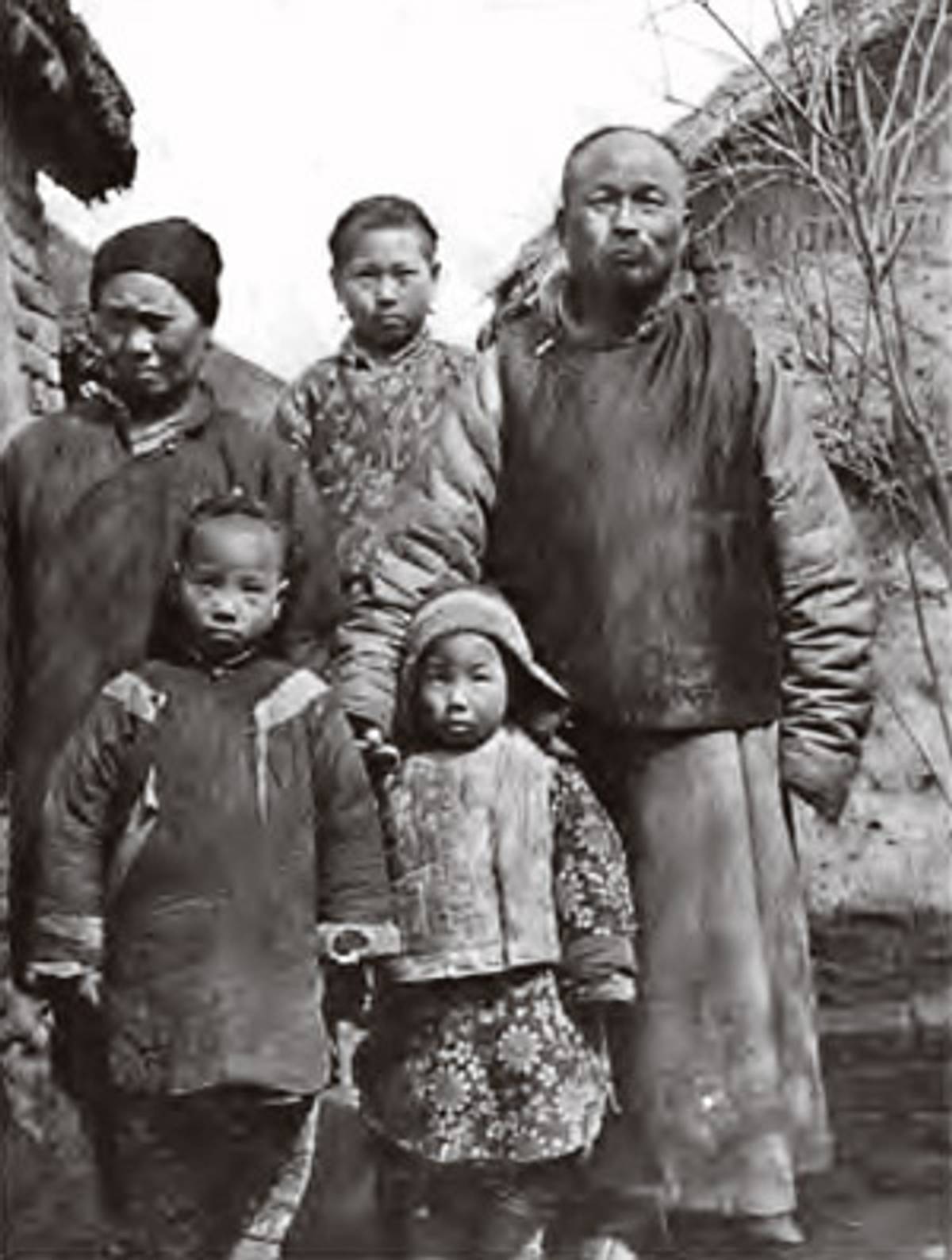

Strangely enough, my first conscious encounter with Pearl Buck did not take place in high school. That’s not to say I didn’t read The Good Earth. But if I did, it made no impression on me: at fifteen I was clearly more impressed by the familiar tales of Victorian romance than those of rural Chinese farmers, fleeing famine.

Twenty-odd years later, however, and vaguely to my own surprise, I found myself writing my own novel on China. I turned back to Buck, reading The Good Earth a little sheepishly on the subway and storing it under the “authentic” Chinese authors (Lu Xun, Ye Zhaouyan) on my bedstand. I was at a loss to explain my vague embarrassment: was it about the derivative nature of a white American woman reading another white American woman about China? Or was it mere vanity; an uncomfortable suspicion that real Brooklyn writers don’t read Pearl Buck—their mothers read Pearl Buck. (Everyone’s mother, someone once said to me, reads Pearl Buck.)

In the end, though, Buck herself brought an end to such frettings. She did it through the sheer force of her achievement: The Good Earth floored me. I simply hadn’t anticipated, well, how good it would be, how its accessible plot and rich details, its simply drawn characters and surprising humor would pull me so fully into the foreign (but never exotic) universe of peasant life in China that such a universe didn’t seem foreign at all. This, after all, is the beauty of Buck, or at least of good Buck: At her best she brings the world’s people together, eschewing literary pyrotechnics in order to—as E.M. Forster advised—“only connect.”

And with The Good Earth, connect she did. Not only was Buck’s second novel hailed as a masterpiece upon publication in 1931, but it was the year’s bestseller, garnered its writer the Pulitzer Prize, and was partly responsible for the Nobel Prize she went on to earn seven years later.

None of Buck’s other books (and there are some seventy of them) would approach The Good Earth in sales or popularity. And to be truthful, few probably approach it in literary merit. “A lot of this stuff might not be very good,” acknowledges Peter Conn, a professor of English at the University of Pennsylvania. Still Conn remains intrigued by Buck, despite his having been “beaten up by some of the inhabitants of advanced English departments” for making her the subject of his engrossing Pearl S. Buck: A Cultural Biography.

Buck’s literary inconsistency, Conn says, stems in part from her fierce dedication to social issues; as her reputation grew she fell into a pattern of writing less to create lasting literature than to fund the myriad causes in which she became involved. An outspoken opponent of segregation as far back as the 1930s, she was called “the current Harriet Beecher Stowe to the Race” by Langston Hughes. (At one literary luncheon she warned that if America persisted in its bigotry “then we are fighting on the wrong side of this war. We belong with Hitler.”) She agitated tirelessly, on behalf of the mentally handicapped (her only biological child, Carol, was mentally disabled, an experience about which Buck writes with painful and unprecedented openness in The Child Who Never Grew) and against social norms that kept thousands of mixed-race and minority children from finding adoptive parents or homes. Welcome House, the adoption agency she founded in 1949, still operates in Pennsylvania and remains a testament to her unfailing dedication to social justice.

Buck’s literary works, by contrast, can be almost breathtakingly uneven, ranging from the sublime to the simply overwrought. And no book, perhaps, illustrate this paradox as uniquely as Peony, her farewell to the disappearing Jews of Kaifeng, China.

Like many tales of Jewry, Peony, published in May 1948, is one of struggle, and of loss. The struggle, in this case, isn’t against the normal dangers (persecution, pogroms, and exile) but against overwhelming acceptance. And the loss isn’t one of life, but of Jewish identity.

Buck sets this surprising tale at the beginning of the nineteenth century, and anchors it in the house of Ezra ben Israel, a jovial half-Chinese merchant, the son of a Jewish father and a Chinese concubine mother. His proud (and purportedly pure-blooded) Hebrew wife is Naomi. Their son, David, up until the story’s opening, is a privileged Jewish Chinese youth, observing kashrut and the Sabbath but also studying with a Confucian teacher and spending his nights moon-gazing in the company of Chinese friends and sing-song girls. The story’s title character—and its Chinese conscience—is Peony, a bondsmaid bought for David as a child.

In unveiling this world, Buck shines a literary light on the little-known intersection of two of history’s oldest civilizations. By the early 1800s, Jews had lived in Kaifeng for at least a millennium. They numbered in the hundreds, and their Chinese-influenced synagogue had been the pride of Chinese Jewry across the vast country. Buck’s description of it is largely in keeping with scholarly accounts: On either side of a beautiful archway, she writes, “stood two stone tablets, each upon a stone base carved in lotus leaves, and upon the tablets were cut in ancient letters the story of the Jews and how they had been driven from their land. Beyond that was the immense platform upon which the great tent was raised at the Feast of tabernacles, and still beyond was the Ark Bethel in the most sacred and inner part of the synagogue.”

As the novel begins, the great temple’s members have embraced Chinese businesses, traditions, and wives, and the synagogue itself has been neglected, as Madame Ezra bewails to the rabbi’s daughter, Leah: “What is happening to our people here in this Chinese city?” she cries in Peony’s early pages. “How few of us are faithful any more!”

“The Chinese are very kind to us,” Leah observes.

“Kindness!” Madame Ezra huffs. “I grow tired of it! Because the Chinese have not murdered us, does that mean they are not destroying us?”

Madame Ezra’s solution is to remake David into a stone wall against the tide of assimilation sweeping her people. She plots to marry him to Leah, partly in the hopes that he’ll one day take the girl’s father’s place as rabbi. Peony, however, seeks to secure David’s heart and mind for herself, and thus China. Fully in love with her master but resigned to the fact that her lowly station will always divide them, she resolves instead to entice David into marriage with a Chinese girl of physical beauty but limited intellect. In so doing, she reasons, she’ll retain not only her place in the House of Ezra, but her position as David’s soulmate and confidante: “You can never be a wife in this house,” she tells herself. “You cannot even be a concubine—their god forbids. But no one knows David as well as you do. You are his possession. Never let him forget it. Be his comfort, his inner need, his solace, his secret laughter.”

Buck weaves her story as a shifting web of wills—Peony’s versus Madame Ezra’s, Madame Ezra’s versus her husband’s, Leah’s versus Peony’s. But perhaps the most important battle takes place within David himself: between the dutiful Jewish son and the easygoing Chinese youth he had been. Well aware his bridal choice dictates not only his fate but his people’s (a point Madame Ezra underscores, with maternal aplomb: “Such a good girl, David—a good wife!” she implores. “Don’t break your mother’s heart! Think of our people!”) he finds himself facing timeless questions: “Would he keep himself separate, dedicated to a faith that made him solitary among whatever people he lived, or would he pour the stream of his life into the rich ocean of human life about him?”

As with her portrayal of his synagogue, Buck’s depiction of both David’s world and his quandary tracks with the factual record. Historians trace Kaifeng’s Jews to eighth-century merchants and traders who arrived via the Silk Road from Persia and India. Jewish communities later sprang up in Canton, Yangzhou, Hangzhou, and other cities. But Kaifeng’s remained the most significant. Its opulent synagogue, dating back to 1163, was maintained largely by the Zhao clan. Here again Buck has done her research; like other Jewish families, the Zhaos used a Chinese name for public and business dealings. Among themselves, they used a Hebrew name: Ezra. It’s likely that Buck—the daughter of missionaries—also appreciated the Biblical significance of that name; after all, it was Ezra who, upon leading Babylon’s Jews back to Jerusalem at the time of the Second Temple, observed with dismay the state of Jewish intermarriage there: “They have taken some of their daughters as wives for themselves and their sons, and have mingled the holy race with the peoples around them. And the leaders and officials have led the way in this unfaithfulness.”

The “stone tablets” Buck describes also have their basis in fact: from the steles, dating back to 1489. Of the original four only two are left, and it is largely from their writings (in Chinese) that scholars have put together what they know of Kaifeng’s Jews. The inscriptions focus less on the history of the community than on instructions for preserving its faith: Tiberiu Weisz, in his new translation (published in 2006 as The Kaifeng Stone Inscriptions) notes that they include “several prayers and blessings, detailed descriptions of manner of worship, and a reminder not to lose their Jewish identity.” At the same time, though—in a nod to their Chinese hosts (if not to the inevitable creep of assimilation)—they also emphasize “that the teachings of the scriptures were compatible with those of Confucius.”

Other reports attest to the acceptance Kaifeng’s Jews found in their adoptive city. Wendy Abraham, in her fascinating afterword to the Moyer Bell edition of Peony, writes that in the seventeenth century, Chinese gazetteers wrote of disproportionate numbers of “Israelites” attaining high rank in government and society by passing the civil service exams. That this required mastery of the notoriously difficult Confucian classics was further testament to how fully they’d adapted to their new home.

Ultimately, however, as had been the case with many ethnic and religious groups in China (a vast country with a long history of absorbing rather than eliminating its opponents) adaptation continued to the point of erasure—if not of the people themselves, then of their ethnic and religious identity. Abraham also reports meeting Kaifeng’s few remaining Jews in 1985. Through a series of conversations carefully monitored by the Chinese government (which stipulated that she could not mention Israel), she concluded that while the remaining Jewish descendents still identified themselves as a unique ethnic group, or youtai, the people she met were “the last generation of Jewish descendants who can even purport to have memories dating back to the early part of this century. Their children and all future descendants can never claim the same place in Chinese Jewish history.”

Peony foresees this stark moment. For in the end it is Peony’s plan, not Madame Ezra’s, that wins the day. Led on a Cyrano-like chase by his wily bondsmaid, David does indeed choose a Chinese bride. The old rabbi dies and the community disintegrates, as symbolized by the crumbling old temple that Peony herself—who ultimately (and somewhat fittingly) has become a Buddhist nun—contemplates many years after the fact: “In the city, the synagogue was now a heap of dust: brick by brick the poor of the city had taken the last ruin of the synagogue away. The carvings were gone, too, and there remained at last only three great stone tablets, and of these three, then only two. These two stood stark under the sky for a long time, and then a Christian, a foreigner, bought them.”

It is a haunting image, that of this forgotten faith in a foreign land, and one I found achingly sad. But Buck embraces this melding of tradition and ethnicity: “Nothing is lost,” she has Peony muse. The blood of Kaifeng’s Jews “is lively in whatever frame it flows, and when the frame is gone, its very dust enriches the still kindly soil. Their spirit is born anew in every generation.”

The response to Peony was somewhat typical for Buck’s post-Good Earth novels. It sold more than half a million copies, and was a Literary Guild selection for June, 1948. Reviews, however, were mixed. While a critic for the Pittsburgh Press staunchly held that she wouldn’t “trade [Peony] for any of the 10 Best on the reading lists today,” Mary McGrory, writing for The New York Times, called Peony a “minor effort…diffused by endless repetition,” while Commentary’s Isa Kapp rejected Buck’s depiction of Judaism as an “intense disembodied force with no reference to the natural manifestations of an ethnic culture or to the actual lively surface of Jewish life.” Similarly, it was surely Buck’s fondness of florid overdescription—which stands in such stark contrast to the manly monosyllables of writers like Ernest Hemingway—that led many critics to dismiss her books as merely “women’s literature.”

And to be fair, it can be argued that no reader—particularly one picking up a Pulitzer-prize-winning author—should be subjected to descriptions such as, “She lifted her eyes to him and her heart flew as straight as a bird from her bosom and nestled in him.” (It is worth noting that at least some of Buck’s hyperbolic style derives not from affectation but translation: She often said that she wrote her Chinese novels in her head in Chinese and translated them into English on the page.)

Such criticisms may be valid. But Peony also offers a glimpse into what makes Pearl Buck so exceptional among American writers. There’s her extraordinary eye for cultural detail; the almost effortless translation of Eastern culture and practice into tales that are not only factually accurate, but entirely sympathetic to a Western audience. There is her relentless championing of the oppressed, and her unabashed (and religiously unbiased) distrust of triumphalism in any form. In Peony, this is manifest in the old and (not coincidentally) blind rabbi who rants against “the heathen” and steadfastly maintains the unique role of the Israelites. “God has chosen my people,” he cries, “that we may eternally remind mankind of Him, Who alone rules. We are gadfly to man’s souls.” They are words that might well have been uttered by Absalom Sydenstricker, Buck’s missionary father, who for more than half a century tirelessly (if unsuccessfully) urged Chinese men and women to embrace Jesus.

As I finished Peony and my short excursion into its author’s life, it struck me that their conclusions were poignantly similar. After centuries of thriving as a unique religious community, the Jews of Kaifeng have slipped into virtual invisibility. Similarly, Pearl Buck (as Peter Conn argues) is largely an invisible woman in American literature. For all her social activism, prolific output, and literary awards, she remains, for most, a name from high school reading lists.

And yet, there may be hope for a renaissance—on both counts. The Sino-Judaic Institute was established in 1984 to help Chinese Jews rediscover their roots; past years have also seen Academic Exchange offices opening in Beijing and Tel Aviv; a pilot Hebrew program has been started at Peking University. And Western scholars who have met with the remnants of Kaifeng’s youtai community report clear interest in reconnecting with Jewish roots. Similarly, there may be hope for Buck’s literary legacy. In China, in fact, she is being rediscovered: scholars at Nanjing University are translating her novels into Chinese, arguing that her naturalist perspective on life in China’s agrarian communities has much to teach.

Hearing this, it struck me that if China is willing to reevaluate Buck’s books, the least we—her own countrymen—can do is the same. I, for one, can now unabashedly say that Peony, The Good Earth, Pavilion of Women, and The Mother have provided both transportive reading experiences and incalculable insight into Chinese culture and daily life in the 1930s, and were of infinite help and reassurance as I, a Western woman, struggled to write a story set in pre-Revolutionary Shanghai. I can’t claim, of course, to write with her level of authority (she spent more than half her life in China, after all), nor promise to read her sixty-odd other books with the same degree of enthusiasm. But in an age increasingly devoted to “insider” stories (to identity politics, memoirs real and faked, tell-all tabloids, and reality-show revelations about people we all seem to know already), her unabashed fascination with outside worlds and unanticipated heroes and heroines feel like breaths of fresh air. And in the end, despite the odd wobbly plot or occasional (or even frequent) overwrought description, perhaps this is Buck’s true, lasting legacy.