Inside Stories

Rutu Modan’s devastating, understated comics

“Reality is more grotesque and strange than anything you can invent,” says the Israeli cartoonist Rutu Modan. “Sometimes life is too much, you have to tone it down to make art.” Modan’s own work has evolved over the past fifteen years from rather strange and grotesque fables into some of the strongest graphic fiction on the planet. Like the novelists David Grossman and A. B. Yehoshua, and young filmmakers such as Hilla Medalia, Modan has found ways to tell stories that use the flood of bad news in Israel as the backdrop to subtle stories about ordinary people learning how to live.

Modan, who moved to England last year when her husband accepted a post-doc position there, has recently been cultivating an international following. Last year her graphic novel Exit Wounds was released in English to widespread acclaim. This year she drew two very different series of comics for The New York Times. Her memoir blog, “Mixed Emotions,” ventured into the realm of autobiography with illustrated stories about her family, such as the fallout from her youngest son’s obsession with a pink tutu, in an ingenious vertical format that would have been cumbersome on paper but worked perfectly online. Her serial mystery “The Murder of the Terminal Patient,” which follows an underemployed Russian doctor as he navigates the hierarchy of an Israeli hospital to investigate a suspicious death, is one of the best comics to have appeared in The New York Times Magazine.

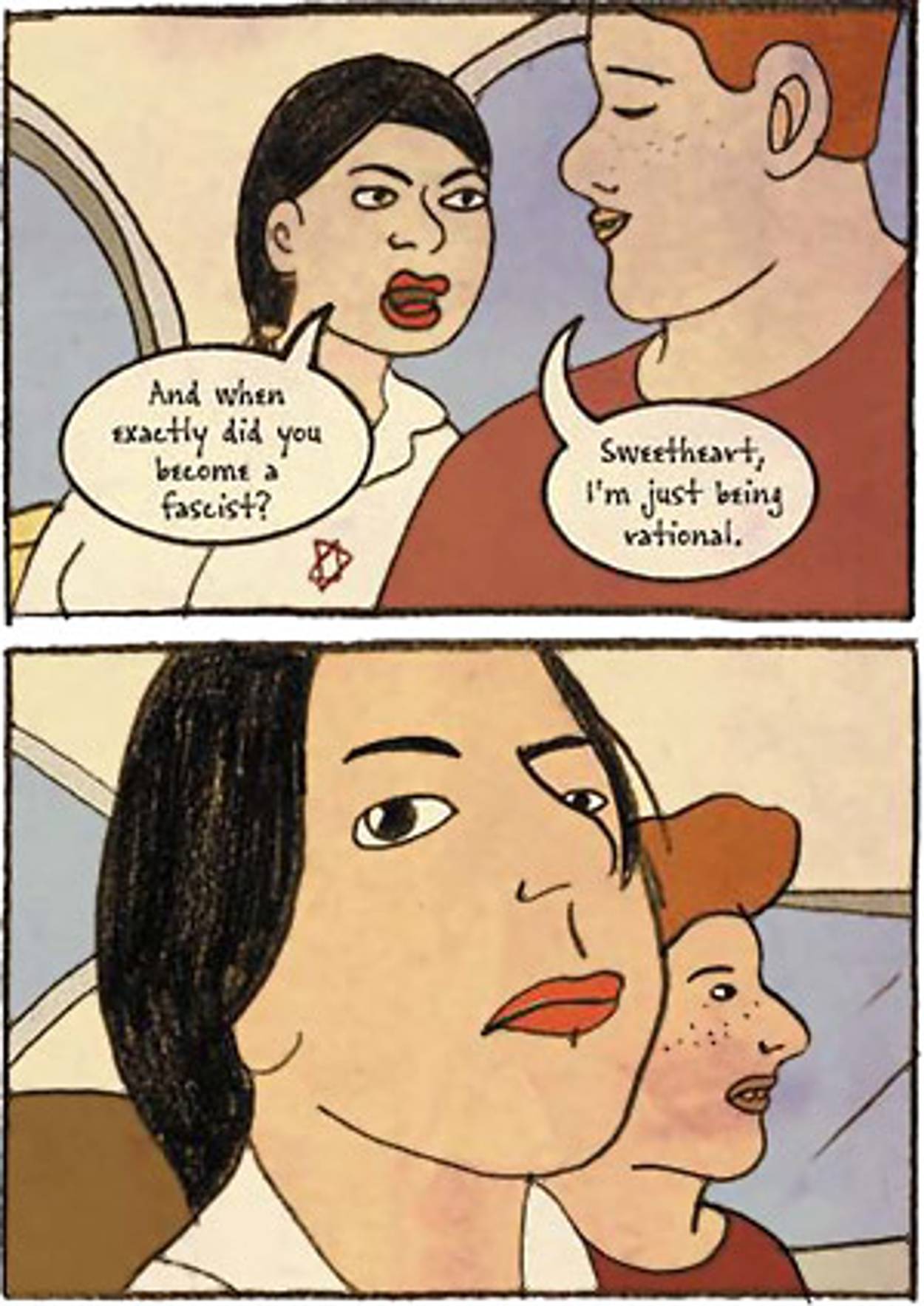

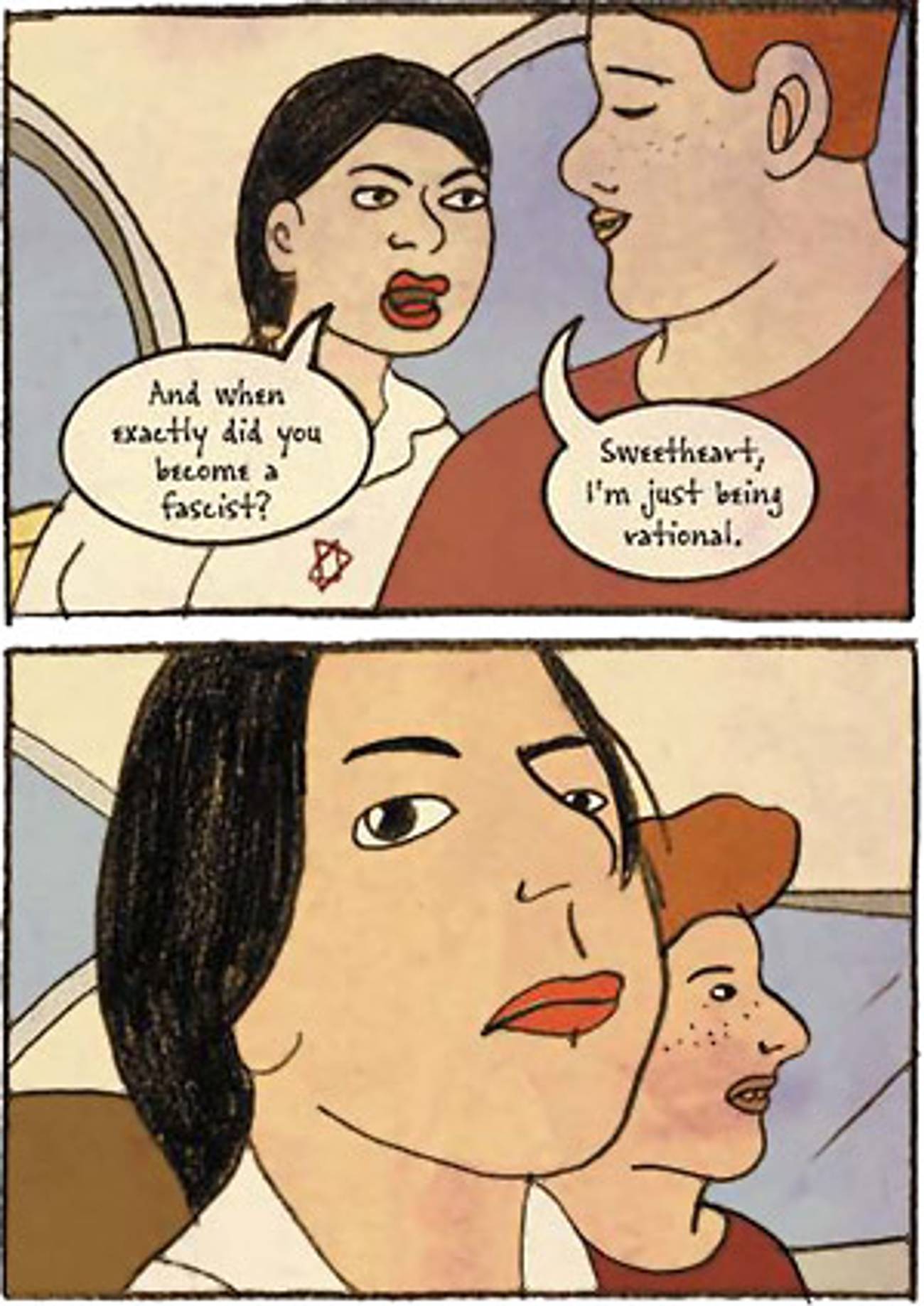

Modan’s visual style may at first appear somewhat plain, but she has a masterful skill for pacing and perspective, a keen eye for postures and facial expressions, and a command of composition and color that rivals the old masters of Sunday comics. Her illustrations recall the whimsical work of Little Nemo creator Winsor McKay, or, as Douglas Wolk has suggested, the “clear line” style of Tintin creator Hergé, where simple characters stand out against finely drawn landscapes to make for an oddly affecting sense of reality. One might wonder how such talent was incubated. Part of the answer arrives this month in the form of Jamilti and Other Stories, a collection of Modan’s early comics released by the Canadian publisher Drawn & Quarterly. Over a decade’s worth of genre experiments veering from fairy tales to crime fiction, Modan emerges in its pages as a storyteller of rare insight and restraint.

Born in Tel Aviv in 1966, Modan’s career has run parallel to the rise of a serious independent comics scene in Israel, which in the past fifteen years has grown large enough to provide a decent market for domestic graphic fiction. Months after first seeing Art Spiegelman’s outlandish magazine RAW as a student at the Belazel Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem, Modan began to publish comic strips that ranged from the absurd to the macabre in local papers. “Since there was no comics tradition” in Israel at the time, she says, “I could do anything I wanted.” In 1993 she was hired to edit the Israeli edition of MAD magazine, along with artist Uri Pinkus. When it folded, Modan and Pinkus decided to start their own comics collective. “If we were going to lose money, better to do exactly what we like,” she says.

The first meeting of the Actus Tragicus collective was convened, as chance would have it, on the evening in 1995 that Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated. The group stayed up all night concocting conspiracy theories in which Rabin survived the shooting. It would be too simple, though, to conclude that this founding trauma set the artists on a path to darker or more cynical work. “This event didn’t change our art,” Modan says. “Israeli reality gives you so many opportunities to be macabre.” Her story-length comics, published in a series of Actus anthologies over the past decade, appeared to seize as many of these opportunities as possible. An early one reminiscent of the Brothers Grimm features a forlorn plastic surgeon who tries to rearrange his patients’ faces in the image of his lost love. In a later story, as hardboiled as it is preposterous, a series of dead bodies turn up bearing the signature of a new serial killer: a pair of panties on the head.

In recent years Modan’s work has become more understated and more revealing as she has grown to engage more fully with contemporary life in Israel. Refusing to shy away from the catastrophes in the headlines, she also refrains from commenting directly on pressing issues like war and terrorism. Instead, Modan tells stories about ordinary people who are confronting their own emotional weaknesses, even as they project strong exteriors to the rest of the world. “In Israel we try to live like political events have no influence on our lives, and most of the time we succeed,” Modan explains. “But it’s a delusion, even if we are not at the center of the drama.”

How thick a skin must you have when you live in a society under siege? This question lies at the heart of Exit Wounds. It follows a bitter young taxi driver as he searches for his deadbeat father, with the help of his father’s wealthy, estranged girlfriend. Its earth tones and mellow pace have a lulling effect on the reader, even as the prickly dialogue reveals enough emotional damage to leave a metal tinge in the throat. The book draws much of its power from the particularly Israeli confusions that drive the story. Was the father tragically ripped away from his son by a suicide bomber before they could reconcile, as it might first appear? Or does the bombing merely give him an alibi to escape from the demands of his own loved ones? In refusing to uncover the truth about what became of his father, is the son succumbing to the fantasy that his life is immune from political events? Or is he simply refusing to give in to the terror-induced hysteria around him? The book offers no clear answers.

The threat of suicide bombings, and the unexpected ways they can twist the mind and the heart, are also central to a pair of the most haunting stories in Modan’s collection. Both are based on real events. In “Jamilti,” the new collection’s title story, an Israeli woman, on the eve of her wedding, rushes to the aid of a man wounded in a suicide bombing. She later learns that the handsome man to whom she gave mouth-to-mouth resuscitation was the bomber himself, his own sole victim. Though the plot may sound contrived, Modan has adapted it from a true story, in which a medic found himself questioning his conservative beliefs after reviving a man who turned out to be terrorist.