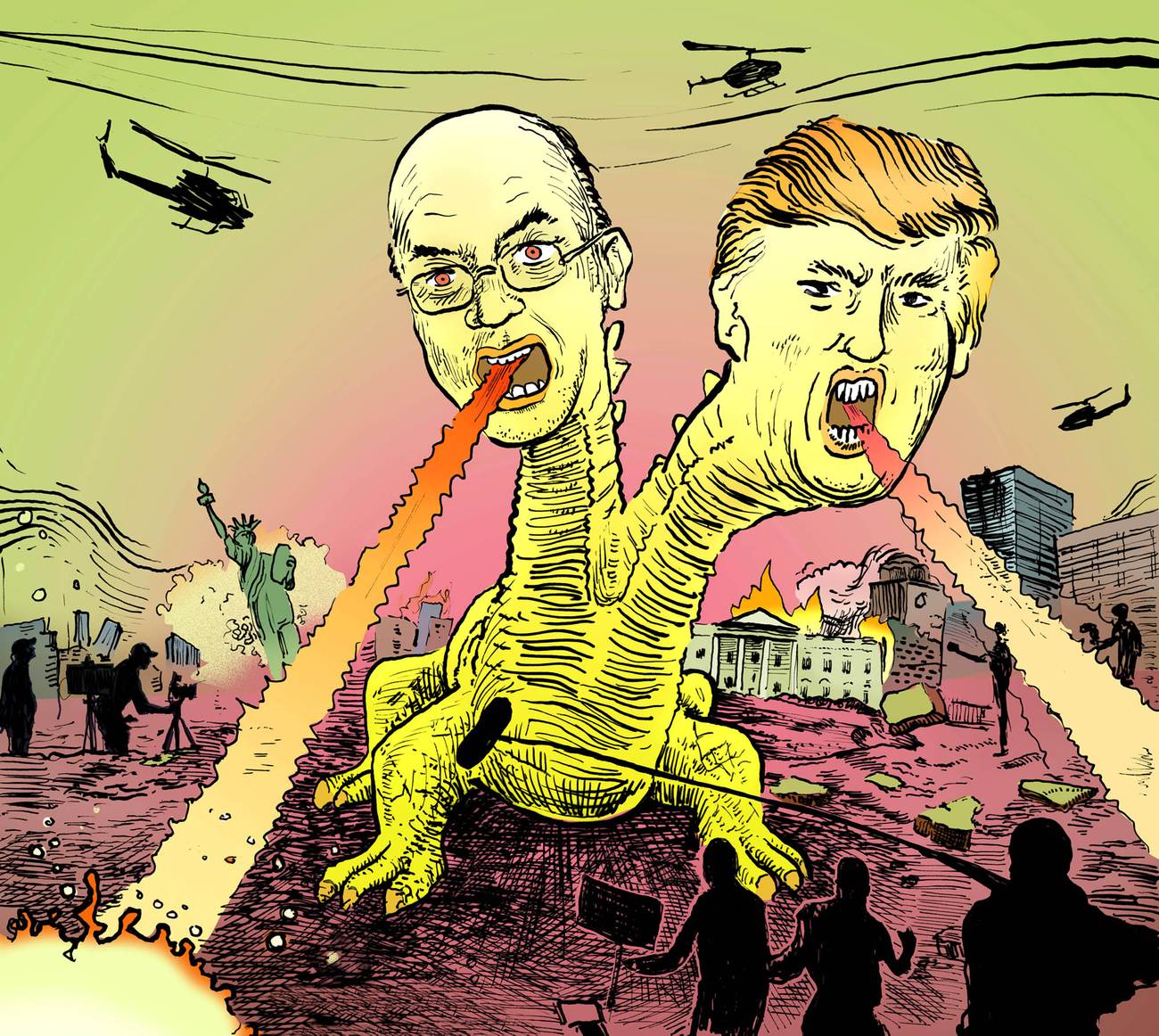

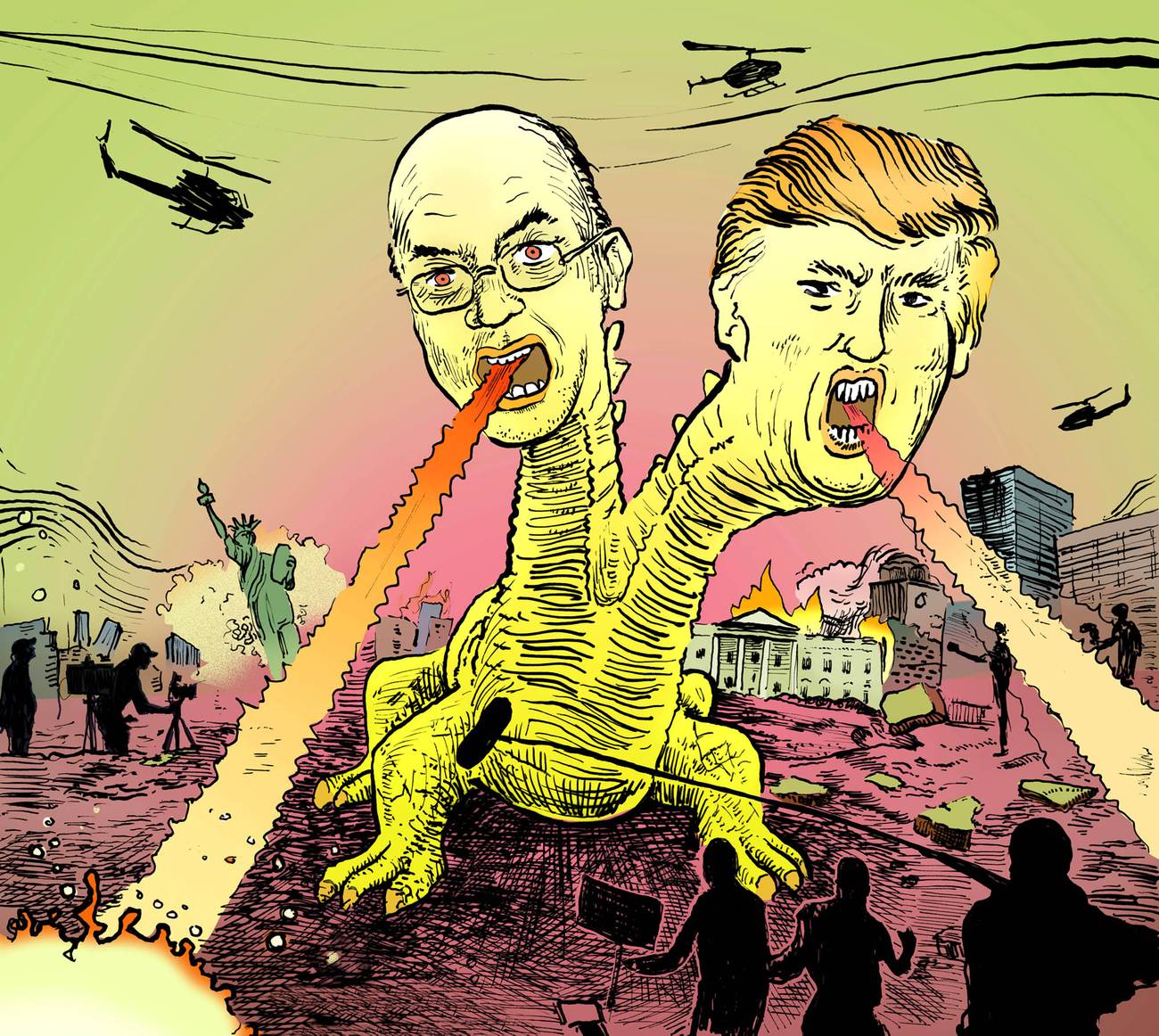

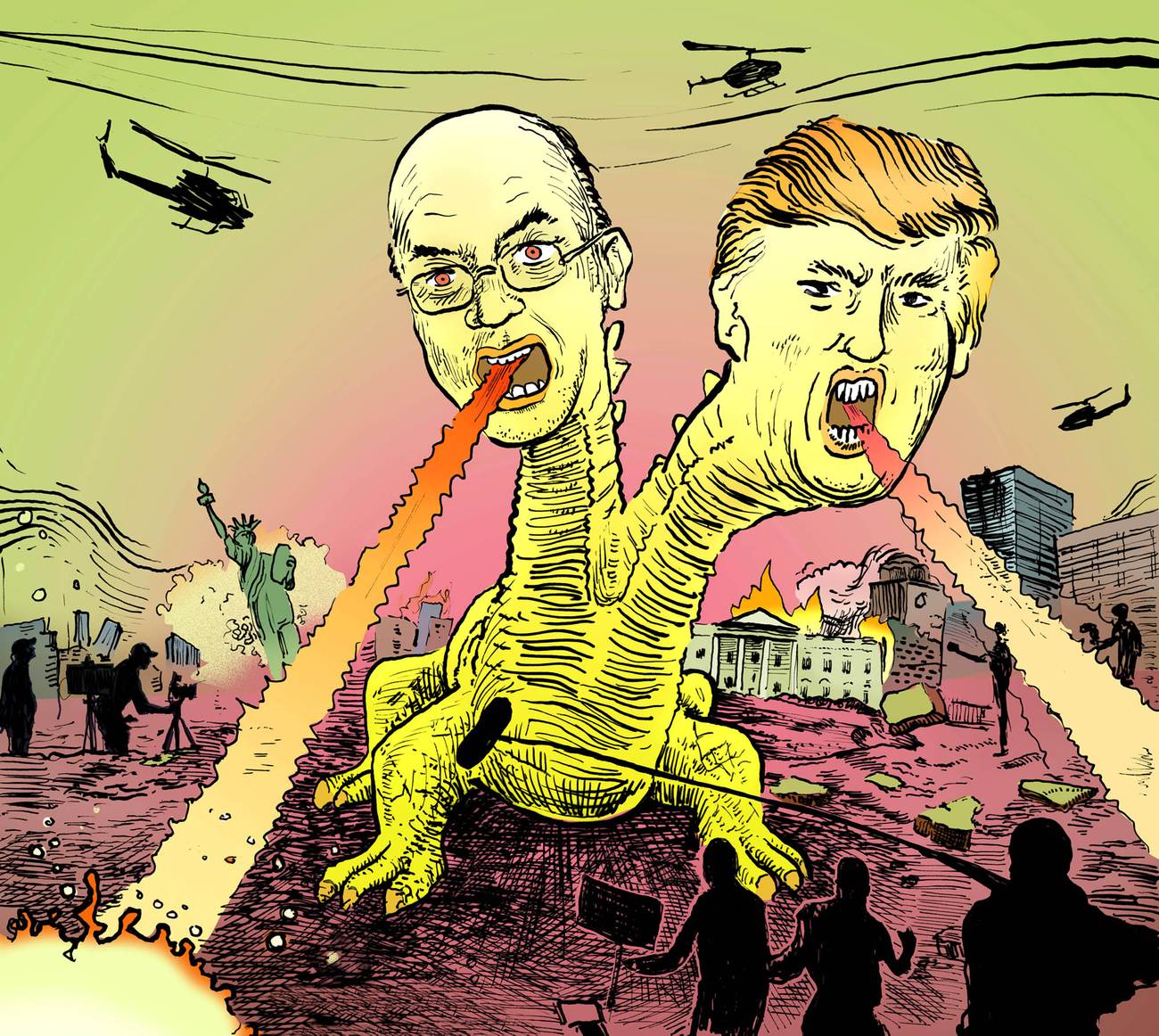

Bullies, Inc.

How CNN head Jeff Zucker’s Miami high school days explain the bizarro alt-reality world of his future frenemy, Donald Trump

America has long been a land where fiction seamlessly turns to fact and fact becomes fiction in turn. Bonnie and Clyde were Depression-era bank robbers before they became screen legends. They also inspired Charles Starkweather and Caril Ann Fugate, two real people who went on a killing spree in the 1950s; Starkweather and Fugate, in turn, inspired Terrence Malick to direct Badlands, his 1973 masterpiece. Walking Tall’s Buford Pusser; Death Wish’s Paul Kersey; Charles Whitman, the Texas Tower Sniper—the list of characters who inspired real people or real people who then became fictionalized characters is long. The never-ending, pingpong match can grow dizzying, but this is how American culture and, increasingly, American politics are made.

Is it any wonder, then, that we elected a former reality TV star as our commander-in-chief? Like a character out of Paddy Chayefsky’s Network or Bud Schulberg’s A Face in the Crowd, our two most prophetic films regarding entertainers as politicians and politics as entertainment, Trump rose from being the butt of late-night TV show monologues and a favorite guest on The Howard Stern Show to the highest office in the land in large part due to the exuberant support of TV news and entertainment executives who considered him ratings gold.

One producer stands out above the rest: CNN’s Jeff Zucker, who, as president of NBC Entertainment, was instrumental in launching Trump’s career on the small screen—turning a brash Queens-based builder into a figure of fiction—a lovable mogul on reality TV—which in turn enabled that fictional figure to become a real-life force who significantly affects the lives of 325 million Americans and millions more persons worldwide.

In contrast to the dozens of books written about Donald Trump, the first book has yet to be written on Jeff Zucker. Yet he is no less deserving of the attention. He began his tenure at NBC as a researcher for the 1988 Summer Olympics and was soon promoted to a field producer position with The Today Show. He became the show’s executive producer in 1992 at the tender age of 26. Eight years later, he was promoted to president of NBC Entertainment. In 2007, at the age of 41, he rose to his highest position within the conglomerate, president and CEO of NBC Universal.

Zucker’s time at NBC Universal was not an unblemished series of triumphs, though. During his oversight of NBC’s Entertainment Division, all of the new sitcoms and dramas that he introduced flopped. By the end of his employment with NBC Universal, the NBC network, which had been No. 1 in ratings when Zucker took over as president of NBC Entertainment, had fallen to No. 4, trailing even the upstart Fox. Maureen Dowd, in a Jan. 13, 2010, column titled “The Biggest Loser,” marveled at Zucker’s ability to seemingly defy corporate gravity when she asked, “How does Jeff Zucker keep rising and rising while the fortunes of NBC keep falling and falling?” Comcast, NBC’s new owner, offered Zucker a golden parachute to leave. Yet, rather than floating off into the sunset of luxurious retirement, Zucker chose to remain in the fray and take on the top job at CNN. He persevered in the teeth of horrendous health setbacks that would have caused most other men to withdraw from such a contentious, exhausting, public life—two incidents of colon cancer before he reached the age of 35, a bout of Bell’s palsy four months into his tenure at CNN, and a major heart surgery in the wake of a corporate shakeup and a divorce. Whatever else may be said about Jeff Zucker, he has shown himself to be indefatigable, virtually indestructible.

What drives Jeff Zucker? What keeps him in a series of pressure-cooker positions when a life of leisure could be his and his health calls upon him to drastically slow down? Is it a need to add more achievements to an already impressively long list of them? Is it a sense of civic altruism? Is it a contrarian sense of defiance, a late-middle-aged rage against health and personal life setbacks that would drag most men down?

I haven’t seen or spoken with Jeff Zucker since we were both 17, so my assessment of his mix of motivations is almost as speculative as that of the average CNN viewer. Almost. Yet there are certain qualities of character that persist throughout a lifetime. Powerful, dominating qualities that steer an individual from one life choice to the next. I witnessed such traits at work while I was a fellow student of Jeff Zucker’s at North Miami Senior High School between 1979 and 1982, and I and some of my friends suffered from them.

Ever since the 2016 nomination of Donald Trump as the Republican nominee, Zucker and Trump have claimed to loathe one another. Yet as someone with personal knowledge of the young Zucker, their mutual antagonism strikes me as the narcissism of small differences. They have far more in common than either man would be willing to admit. Just as I won’t deny the possibility of civic altruism and a hunger for achievement playing roles in Zucker’s motivational set, I believe President Trump is driven in part by love of country and his sense that he possesses indispensable skills for setting things right.

Yet both men seem to also be driven by a quality less praiseworthy—a need to crush and humiliate rivals and opponents who seem vulnerable or weak. An eagerness to bulldoze aside truth, decency, and compassion in pursuit of triumph and self-aggrandizement. I first noted this about Trump when, during the 2016 primary, he fanned the flames of a ludicrous conspiracy fable about Ted Cruz’s father having been involved in President John F. Kennedy’s assassination and then, not satisfied with just this, made sophomoric taunts about Cruz’s wife. My observations about Jeff Zucker go back much earlier, to three years of high school during which he took satisfaction and personal delight in tormenting those he could.

The one word that most closely ties the two men together?

Bully.

Not unlike Donald Trump, Jeffrey Zucker was born into a life of privilege, although to a somewhat lesser extent. He grew up the son of a well-off cardiologist and a teacher, living in a large house in the exclusive Sans Souci Estates subdivision of North Miami, Florida, a block or two away from the sun-dappled waters of Biscayne Bay. He attended public schools, but they were solidly middle class and upper middle class. He was bar mitzvahed in one of Miami Beach’s biggest, swankiest Reform temples and celebrated afterward in the Starlight Roof ballroom of the oceanfront Doral Hotel.

I didn’t attend Jeff Zucker’s bar mitzvah. I didn’t yet know him when we were both 13. I met him about a year and a half later, when we both started 10th grade at North Miami Senior High School. My family’s house sat on the dividing line between North Miami and North Miami Beach, in an inland, more modest neighborhood than Sans Souci. My father was an unsuccessful insurance salesman who lived in a series of furnished apartments, and my stepdad was also a salesman, a more successful one who sold folding boxes to firms such as Burger King and Disney World.

I was on the younger side of my 10th grade cohort; I still had two more months to go as a 14-year-old when I started at North Miami Senior. Jeff Zucker was five months younger than I was, which makes me think he must’ve skipped a grade at some point. I was average-sized for my age, maybe a little smaller than average—about 5-foot-6-inches and 120 pounds, gangly and unathletic, wearing my curly hair long, in what my friends would teasingly call a Jew-fro. I had been the top student at my junior high school, Thomas Jefferson, a rough-and-tumble school that abutted I-95 about three miles west of my house, to which I’d been bused as part of a school desegregation arrangement. I’d had few friends at Thomas Jefferson. I began turning that around once I arrived at North Miami Senior by joining the drama club. But I remained socially awkward and proudly dedicated to my studies, carrying a day’s worth of books with me everywhere, balanced on my hip, rather than park some in my locker and risk being late to class.

Since many of my classes were either honor or Advanced Placement classes, I often shared a classroom with Jeff Zucker. But my earliest memories of him were from the playing field alongside NE 135th Street, where our physical education coaches had us playing touch football. Clumsy and not big or fast, I invariably ended up assigned by my team to be a pass rusher, using a few tips my more athletically inclined father taught me to avoid looking entirely hapless. I was astonished to see a diminutive kid, no bigger than a typical seventh grader, frequently talk his way into being a team quarterback. I was on the smallish side, but Jeff Zucker was tiny—he barely crested 5 feet tall, and he was every bit as skinny as I was. Yet there he stood at the center of the huddle, barking orders to classmates 8 to 12 inches taller than he was, who outweighed him by 50 to 80 pounds—any one of whom could’ve picked him up by the scruff of his neck and deposited him head down in a trash can, if they’d been of a mind to. I recall hearing a bit of grumbling from the other kids about Zucker’s insistence on playing quarterback. But more often than not, through sheer force of will, he got his way. Who is this guy? I asked myself. And how does he pull this off?

He proved to be a striver both on the playing field and off. He became captain of the school’s tennis team and ran successfully, three years in a row, for class president, under the banner, “The Little Man with the Big Ideas.” I came to view him as “The Little Man with the Great Big Balls.” We shared a teacher, Mrs. McIntyre, for honors English in both 10th and 12th grades. Mrs. McIntrye had the face and figure of a kindly garden gnome. At 4-foot-10 or so, she was even shorter than Zucker, and she was rather thick-waisted and squat. She adored Jeff Zucker. He called her “Stump Woman.” Not merely behind her back, but to her face, in front of the class. She simply grinned at him and gently shook her head and said something along the lines of, “Now, Jeff, you be nice, you hear?” She sensed, and he knew she sensed, that Zucker would be the most prominent student she would ever have; he already showed indications he would excel in her field of tutelage, having become editor of the school newspaper, working as a teen-beat stringer for The Miami Herald, and being selected a participant in Northwestern University’s High School Institute for journalists. He was her pet, her trophy, and he knew exactly how far to push her—not so far as to get himself in trouble, but far enough to jokingly flaunt his arrogance and his social dominance of a teacher.

His domineering behavior was far less measured and restrained when it involved interactions with his peers ... at least those peers lower than he was on the social or academic pecking order. I witnessed a characteristic of Jeff Zucker that was entirely absent from the other middle-class and upper-middle-class, high-achieving students with whom I shared classrooms, who were generally mild, reasonably good-natured, mannerly, and polite. This was a personality trait I had previously encountered only in the coarse young rednecks with whom I’d been forced to share a bus stop in junior high, boys who had taken to tormenting me for the fun of it by taunting me and pelting me with rocks. What I had seen in these bullies and what I now saw in Jeff Zucker was a desire to hurt those who posed no threat—an accrual of pleasure through wounding those who were physically weaker ... or psychologically weaker. My street-corner bullies had gotten away with it because they’d been bigger than me. Conversely, Zucker got away with it because he was so small—anyone with a sense of fair play (and he always was careful to choose victims who had a sense of fair play) wouldn’t lay a hand on him because he was so physically puny. So long as he didn’t screw up by psychologically needling someone lacking scruples, his size shielded him from getting the snot kicked out of him.

My friend Iyob (name changed) fit the profile of Zucker’s victims to a tee. Iyob and his mother had emigrated to the United States from Syria; as an immigrant from an impoverished country, he was well below Jeff Zucker, scion of a Sans Souci cardiologist, on the socioeconomic pecking order. Iyob was gentle and self-effacing and lacked self-confidence; smart and ironic and funny, most of his humorous barbs he applied to himself. He was certainly not the sort of boy who was confident, bold, or mean enough to pose a retaliatory physical threat to Zucker. A classmate in most of my honors and AP classes, Iyob was a classic underachiever; although just as intelligent as any of his classmates, he never lived up to his potential in high school. He floundered academically, earning grades in the lowest third of his cohort and barely hanging on to his status as an honors student.

Zucker honed in on Iyob’s insecurities and marginal status like a dwarf shark scenting the blood of a shipwrecked sailor. His favorite occasion on which to put the screws to Iyob was in the wake of an exam. After the teacher had handed back the graded test papers, face down, Zucker would make a beeline to Iyob’s desk as soon as the period ended, before my friend could depart the classroom. “What’d you score, Iyob?” Zucker would sneer. Rather than telling Zucker to fuck off, as would’ve been appropriate, Iyob would invariably mutter his grade in an undertone—usually a score below 75%. Zucker would then triumphantly flash his own graded paper—typically scoring 95% or higher.

Of all the persons I had personally known, the one who had achieved the greatest worldly success, approbation, and influence was the one I considered to be the worst human being I had ever met.

Iyob wasn’t the only one of my friends on the receiving end of Zucker’s low-level sadism. I had attended school alongside Rachael (name changed) since our shared kindergarten class at Temple Adath Yeshurun. We’d gone through elementary school, junior high, and now high school together. I had long harbored feelings for Rachael somewhere between friendliness and a crush—even as a little girl she was beautiful in a distinctly Eastern European Jewish way, with gorgeous eyes. During junior high her figure had filled out to nothing less than statuesque. Although I was a distant satellite of her social circle due to our long acquaintance, I remained a silent admirer, always assuming she was well out of my league. She continued filling out during high school, acquiring a plushness that, while very appealing to me, did not fit the narrow notions of high school hotness. She also acquired, sadly, a serious crush on Jeff Zucker, a fact she made well known, often gushing about him to friends where I could overhear. I tried hard to figure out the source of his attractiveness for her—he was handsome, yes, in a miniature poodle sort of way, but she was at least 4 or 5 inches taller than he was. Perhaps, I thought, it was the unusual, Napoleonic combination of his childlike diminutiveness (that brought out her mothering instinct) and his pretension of alpha-male dominance (that appealed to her feminine submissiveness) that made him seem irresistible to her?

How he enjoyed bad-mouthing her behind her back, laughing with their shared friends about her “fatness” and “piggishness” and how unshakable her devotion to him was, no matter how poorly he treated her. I watched him do it, observing him from a distance. I’m certain his ridicule got back to her. But she continued pining for him throughout high school, perhaps justifying his loutishness as a rough form of affection, absorbing his abuse and seeing him through a softening glow, just as Mrs. McIntrye did.

Zucker didn’t pull his post-exam “what’d you score?” move on me; not more than once or twice, anyway, when he didn’t get the result he wanted. My grades were just as good as his, and had he scored a 95% on a test, there was always a chance I might’ve scored a 98, and he did not want to risk possibly losing face. However, he found another, less risky way to probe my vulnerabilities, apart from picking on my friends.

Wanting to have a vehicle with which to transport my drama club’s sets to theatrical competitions, I worked summer and after-school jobs to save up enough money by my senior year ($1,200) to buy a truck, a 1975 Ford Ranchero pickup. Its bed was badly rusted through, but a friend’s father’s handiness with fiberglass took care of that. In those days of cavalier attitudes to road safety, prior to mandatory seatbelt use—this was 1981 or 1982—I often packed two or three friends into the bench seat in the Ranchero’s cab and carried another half-dozen or so in the open bed. One afternoon after the last classes let out, friends and acquaintances gathered around my truck for rides home. Jeff Zucker surprised me by telling me he wanted me to drive him home, too.

He knew that I couldn’t stand him. He also knew that I was conflict-averse and had a self-image as a mensch, a nice Jewish boy, someone eager to be accommodating. I’m sure Zucker could easily have bummed a ride off an actual friend, or paid for a cab, if necessary. An ordinary person would not ask someone he did not like, and whom he knew did not like him, for a ride home, especially one that would take the driver well out of his way. But Jeff Zucker was no ordinary person. He wanted to see what he could get away with. And really, there was no way for him to lose—if I refused him, I’d look petty in front of my friends, and if I accommodated him, I’d hate myself. I played this all out in my head; I fully recognized what was going on. This was another form of a staring contest, to see who would blink first. I blinked—I didn’t want to be rude. Zucker had read me like an instruction manual. I told him he could jump in back, and I drove him home, seething at myself the whole way.

High school kids mentally elevate the events in their lives to high drama, and I was by then president of the drama club (in truth, I was). At a loss regarding what to do about Jeff Zucker, I approached an adult I considered a mentor, Mr. Wimmers, who had taught both me and Zucker AP philosophy and European history. Mr. Wimmers, one of North Miami Senior High’s more bohemian (and popular) teachers, whose cozy classroom occupied an A-frame attic far from the bustling hallways and administrative offices, considered my dilemma. Eyes sparkling, he grinned, puffed on his pipe, gripped my shoulder and said, “Pull him into the bushes and beat the shit out of him!”

Alas, had I taken Mr. Wimmers’ advice! The subsequent unfolding of American broadcasting and political history might have turned out very differently—a chastened Jeff Zucker might have become a sports writer at a midsize newspaper in Central Florida, and Donald Trump might still be building casinos and stamping his family’s name on cuts of beef. (Or Zucker’s family might’ve sued my family and I might’ve lost my full-tuition scholarship to Loyola University.) Zucker was virtually the only senior at my school puny enough that I would’ve stood a darned good chance at successfully beating the shit out of him. But as much as I wanted to carry out Mr. Wimmers’ suggestion to the letter, I instinctively told myself I wouldn’t do it—because Zucker was so puny, and I considered myself too much a mensch.

Following the end of our penultimate semester at North Miami Senior High, the school issued the academic rankings for its Class of 1982, more than 500 strong. Jeff Zucker tied for fourth rank, and I came in right behind at sixth. That final semester, the pressure was off; our final grade-point averages had already been calculated and sent off to the colleges we’d applied to, and our class rankings were set in stone. Yet Zucker continued gaming the system, even when it was no longer to his advantage. During one study hall session, in which the teacher excused him or herself and left us honorable honor students to our own devices, I came across Zucker and a cadre of other top-ranked students huddled in a supply closet, studying an answer sheet for the upcoming honors physics exam that one of them had purloined.

Zucker invited me to join the cheating session. I turned him down. It wasn’t just my self-image as mensch at work; I realized he wanted to bring me down morally to his level, along with as many of the school’s top-ranking scholars as he could. Perhaps he felt that, by bringing his peers down, including the class salutatorian, he elevated himself. Perhaps, yet again, he was attempting to push his limits, to see what he could get away with, to test how much influence he could wield.

Right before graduation, Iyob and I managed to extract a small measure of revenge—rather than a pound of flesh, several pounds of toilet tissue. Late the night of the senior prom, after Iyob and I had dropped off our dates and doffed our tuxedos, we drove into Sans Souci Estates, the bed of my Ranchero partially filled with huge family-size packages of toilet paper rolls. At some point past 3 in the morning, we spent about an hour thoroughly toilet-papering Jeff Zucker’s house and the trees in front. To make sure everyone in the neighborhood would understand at whom the insult had been hurled, we spelled it out in giant letters on the front lawn—LITTLE SHIT, written in long strips of toilet paper that, dampened by the early morning dew, stuck to the grass tenaciously.

To this day, I hope his father forced him to clean it up.

Jeff Zucker finally achieved his long-delayed growth spurt sometime in college, at Harvard. He is at least several inches taller now than I am, I believe. I learned this second-hand, from photographs in news clippings my younger sister would send me, in order to tease me, each time Zucker achieved a new milestone or was the subject of another flattering magazine profile. It pained me to follow his career, but I was unable to look away. What irked me the most, a burr caught between my foot and my shoe, was the knowledge that, of all the persons I had personally known, the one who had achieved the greatest worldly success, approbation, and influence was the one I considered to be the worst human being I had ever met. Having the moral loathsomeness of the powerful insinuated through works of fiction, such as A Face in the Crowd or Network—even reading stories of malfeasance and corruption among the overclass in the news—that was one thing. It was far away. One could sigh, then shrug, figuring the rot was at a distance, abstract, maybe even overblown, but in any case not really affecting everyday life. But having gone through high school with a little shit who rose to become one of the most powerful men in America—that was a bucketful of cold water, a personal revelation that forced me to question the sort of leadership our society elevates to the top.

It wasn’t the narcissism or calculated cunning or unceasing competitiveness that disturbed me—depending on circumstances, those traits could be a blessing, powering one through obstacles and setbacks that would stop a less determined soul cold. What disturbed me wasn’t even so much what I suspected was Zucker’s special talent for kissing up and kicking down; large bureaucracies being what they are, that’s a well-proven strategy for success, if not for menschlecheit. No, what repelled me the most was his unnecessary cruelty, the manner in which he had gone out of his way to inflict emotional hurt on those he judged to be psychologically weaker than he was.

The convoluted relationship between Zucker and Trump, these two “kings of New York,” verges on the Shakespearean—or if not quite Shakespearean, then certainly Schulbergian. Two bullheaded strivers, each with an ironbound confidence in his own worthiness, but each nursing a festering narcissistic wound—Trump trying to prove himself worthy of the company of Manhattan’s glamoratti by showing he wasn’t just a kid from Queens born with a silver backhoe in his mouth; Zucker overcompensating for once having been too small and frail to play quarterback in a Pop Warner youth league. One desperate for media adulation and affirmation and willing to make a spectacle of himself, the other desperate for ratings and willing to offer access and legitimacy. Brothers from another mother. Ideal partners, both similar and complementary. Two men for whom their ends justify their means.

The record left by New York City’s gossip sheets contains tantalizing tidbits concerning the nature of Zucker and Trump’s relationship and its distinctly symbiotic aspect. In a 2011 interview, Zucker said about his former reality TV star associate, “I understood who and what Donald Trump was because I was from New York and I understood that he was just a one-man-wrecking-publicity machine ... nobody could generate publicity like Donald Trump.” Zucker attended Trump’s 2005 wedding to Melania Knauss, along with Bill and Hillary Clinton. He asked his friend if NBC could televise the wedding. In what is surely one of the only instances of Trump turning down free publicity, the groom declined. Perhaps it was inevitable that a man possessing Trump’s narcissism, hunger for attention, and broad circle of media and political contacts would be attracted himself to politics. True to his outsize self-regard, he had to start at the top. He made an exploratory run for the presidency under the Reform Party banner in 1999, then toyed with running for the Republican nomination in 2012. Three years later, when he thought that the third time might prove the charm, he naturally reached back to the media titan, now president of CNN Worldwide, with whom he’d enjoyed his longest and closest relationship.

In a January 2017 interview with New York magazine, Zucker was asked if he had been regularly in touch with Trump throughout the recent campaign. He initially responded, rather defensively, “Obviously we’ve known each other for a long time. Just because I’ve known somebody for more than 15 years doesn’t mean they get a pass.” When pressed further, regarding the frequency of talks or phone calls over the course of the campaign, he replied, “Probably once a month?” What did the two buddies discuss during these conversations? We’ll likely never see the transcripts, but an anonymous Zucker associate related this to The Wrap regarding the primary season exchanges between Zucker and Trump: “Donald would say to Jeff, ‘Can you believe I’m going this far?’ Behind the scenes they would kind of joke about it. ... I don’t think anyone expected it to go this far. They were friendly during the campaign.”

What unfolded was an arrangement of mutual benefit. CNN granted Trump’s campaign eight times as much air time as the network devoted to his closest primary rival, Ted Cruz. As a result, CNN’s prime-time viewership in early 2016 increased by 40% over its January 2015 numbers. After having been regularly clobbered by its cable news rivals, CNN fought its way to the top of the ratings heap in late 2015. Zucker described his philosophy regarding the presentation of television news thusly: “The idea that politics is sport is undeniable, and we (CNN) understood that and approached it that way.” This outlook—that politics is primarily a contest between personalities, rather than a forum in which the public can decide between competing ideas of the common good—proved especially congenial to Trump’s political style. Paddy Chayefsky would have recognized Zucker’s philosophy; it is essentially the same as that promoted by Network’s Diane Christensen: news as infotainment.

The bromance seemingly soured when Trump secured the Republican nomination. During the general campaign and subsequent to Trump’s election, Zucker transformed CNN, formerly viewed as the “middle of the road” cable TV news network, into a partisan outfit akin to MSNBC. His network provided breathless, wall-to-wall coverage of Russiagate, personnel turmoil in the White House, the impeachment saga, and every mean tweet Trump published. Their relationship deteriorated into mutual loathing. In August 2018, Trump tweeted, “The hatred and extreme bias of me by @CNN has clouded their thinking and made them unable to function. Little Jeff Z has done a terrible job, his ratings suck, & AT&T should fire him to save credibility!” The personal pettiness and level of vitriol displayed by this tweet are striking, especially coming from a sitting president and aimed at a man, a former friend, recovering from heart surgery. Most revealing was Trump’s selection of “Little Jeff Z” as his term of derision. Trump has always selected nicknames for his opponents with care, aiming for his foes’ Achilles’ heels. His choice of “Little Jeff Z” showed Trump’s in-depth familiarity with Zucker’s past. It was a case of one bully bullying another.

What would Schulberg or Chayefsky make of such tempestuously passionate, treacherous, venal, petty, and yet historically portentous material—a mix of high and low, drama and comedy; a love-hate relationship for the ages? Or if not for the ages, then certainly for and of our time?

I believe their screenplay would have more twists and turns than the Tail of the Dragon. I figure it would feature a series of secret meetings between its two protagonists prior to and during the 2015-16 primary campaign, during which they would discuss common and mutually supportive interests. The former would include getting their shared friendly acquaintance and potential benefactor, fellow New Yorker Hillary Clinton, elected president. Trump would commit to his “one-man-wrecking-publicity machine” shtick, acting as a human bowling ball and knocking the possibly dangerous conventional Republican candidates on their asses, roughing up the eventual nominee so that he/she would be easy pickings for Clinton in the fall. A Clinton presidency, with its globalist leanings, would economically benefit both Trump and Zucker. Their mutually supportive interests would include Trump’s desire to build his personal brand and Zucker’s desire to build CNN’s ratings.

But then the unthinkable happens—Trump wins the nomination. (At this point, Chayefsky and Schulberg would be sorely tempted to plagiarize the final line of dialogue from Robert Redford’s 1972 film The Candidate: “What do we do now?”) Trump, caught up in his narcissistic daydreams of being a Man of Destiny, decides to believe his own bullshit about other countries kicking sand in America’s face and globalist elites pissing on the heads of Real Americans while enjoying the smells of their own farts. Or maybe he’s believed it all along, having long suffered the scorn of Manhattanite snobs as a scion of workaday Queens. He bats aside Zucker’s plea that he take a dive in the general. Zucker, faced with the very real possibility of ostracism from his social circle for having built up Trump, applies an even greater zeal to tearing him down. Things only turn nastier after Trump’s shocking election. But the inverted dynamic continues benefiting them both. Zucker helps build an audience of passionate Trump-haters and then sustains CNN’s ratings by continually feeding them the red meat they crave. Trump declares the media in general and Zucker in particular to be “enemies of the People” and strokes his base’s basest instincts by thrusting sharp tweets into Zucker’s villainous hide.

That’s just the skeleton of the plot. Chayefsky and Schulberg would hang thick, juicy slabs of subtext onto this frame. About the abandonment of the ideal of journalism as a public trust. About turning away from the notion of politics as a series of compromises painfully negotiated for the common good, instead adopting a vision of politics as a series of contests between enemy forces, always with a winner and a loser. About the erosion of once commonly held ideals of civility, decorum, fellowship, and a fair hearing for all sides. About the elevation of the lowest instincts of the playing field to the commanding heights of our society.

I’d pay full price to watch that movie in the theater. It would bring back my teenaged memories of Jeff Zucker. It would make me think about how some CNN news narratives, like their coverage of Covington Catholic High School student Nick Sandmann, feel just like Zucker’s treatment of my friends Iyob and Rachael. Cruelty for the hell of it. Picking a target because it’s convenient and probably won’t hit back and it makes you feel good. Makes you feel big.

Andrew Fox is the author of, among other titles, Fat White Vampire Blues.