Jewish Writing During Wartime

A continuing journey through Ukraine takes us to the literary capital of the bloodlands

Courtesy the author

Courtesy the author

Courtesy the author

Courtesy the author

“Hitler got rid of the readers. Stalin got rid of the writers.”

- Katja Petrowskaja’s father, professor Miron Petrovsky

“No matter how bad things get you got to go on living, even if it kills you.”

- Sholem Aleichem

Since I was traveling around Ukraine paying tribute to Jewish writers and the cities they worked in, I had two in mind for Kyiv. One is arguably the most famous Yiddish writer of them all, Sholem Aleichem, whose stories practically define the East European Jewish experience of the last years of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th.

The other is Katja Petrowskaja, who was born in Kyiv in 1970, emigrated to Germany in the last year of the 20th century, and in 2014 published a family chronicle, Maybe Esther, that has garnered a slew of international prizes and was translated into more than 20 languages.

In between the years Sholem Aleichm left Ukraine at the beginning of the 20th century and Katja Petrowskaja settled in Berlin at the end of it, a great deal happened to Jews in that country, most of it horrifying beyond belief. That two decades into the next century, 73% of Ukrainian voters would elect a Jewish comedian as president doesn’t make things less complicated, while Russia’s president has seethed and ranted that Ukraine is currently being run by drug-addled homosexual antisemitic child molesters. They can’t all be right.

I. Sholem Aleichem’s Kyiv

I arrived in Kyiv late on a September weeknight after having spent a day in the front-line city of Zaporizhzhia, where I met with high school and university students who have a Jewish history club. I slept in a hotel favored by international aid workers (read: cheap) and in the morning strolled down Shevchenka Boulevard.

In downtown Kyiv, where even in wartime traffic moves like sludge around five-star hotels, glass office blocks, and elegantly restored older buildings, I found one particularly glitzy shopping mall with tenants like Dolce & Gabbana, Chanel, Yves Saint Laurent, and Tiffany. In the midst of all this bling stood the entrances to two museums: a contemporary art gallery named after the businessman and philanthropist Viktor Pinchuk, and the Sholem Aleichem Museum.

I knew what was in store for me, as Jonathan Brent, director of YIVO, the Jewish Institute for Research in New York, had visited the museum in 2011 and spoke about it on video. He was, I would soon see, rightly less than impressed.

Courtesy the author

The museum isn’t bad if you’re into little dolls wearing Orthodox garb, but what made the visit worthwhile was the lanky and cheerful Rafael Litwin, the curator of the musem, who began by saying that back in 1888, Sholem Aleichem had lived right around here, although the original building is long gone and the streets have been broadened and rerouted.

Rafael, who could be Google’s own walking Sholem Aleichem app, told me that the man referred to as the Jewish Mark Twain had been born in 1859 as Sholem Rabinovitch in the shtetl of Peryaslav, around 85 kilometers south of Kyiv. After his mother died in 1872, he and his brother lived with their grandparents in nearby Bohuslav before returning to Peryaslav, where Rabinovitch completed school in 1876 and was hired as a tutor for a rich man’s daughter. The family lived on a huge estate outside Bohuslav.

When Loyeff realized that the 21-year-old tutor he had hired three years earlier and his 16-year-old daughter Olga were in love, Loyeff left an envelope with cash in it for Rabinovitch and sent the lad packing.

Sholem moved to Kyiv and landed a job with an attorney, where he was promptly swindled. He should have taken his own advice, which I found in his autobiography, From the Fair: “If you’re afraid of wolves, don’t go into the forest.”

In 1883 he and Olga married and her father invited the young couple to move onto the family estate. They soon had the first of six children.

This was also the year Rabinovitch released his first story in Yiddish, “Two Stones,” which he published under a new name: Sholem Aleichem, Hebrew for “how do you do.” The name would stick.

When Olga’s father died in 1885, he had no male heirs and left everything to her. But Russian law required her to turn it over to her husband. According to Jeremy Dauber’s lively biography The Worlds of Sholem Aleichem, the inheritance would be $2.6 million in 2010 dollars (the year Dauber published his biography). It took Sholem Aleichem five years to run that fortune into the ground, declare bankruptcy, and go into hiding from creditors. “He lost quite a lot by gambling in stocks,” Rafael said.

In between the years Sholem Aleichem left Ukraine at the beginning of the 20th century and Katja Petrowskaja settled in Berlin at the end of it, a great deal happened to Jews in Ukraine, most of it horrifying beyond belief.

The family lost their well-padded apartment in the center of Kyiv and moved to Odessa in 1890. Olga, who had had some training as a dentist, set up an illegal clinic in their home while Sholem Aleichem spent the next decade churning out stories that made their way around the Yiddish-speaking world.

When pogroms swept Ukraine in 1905, Sholem Aleichem’s family moved to America. He had trouble in New York, too, Rafael said. “In New York, he was welcomed as a hero, and he wanted to get into the film business, but his partners cheated him.” Rafael’s eyebrows went up, then down. “As I said, he had trouble with money.”

Sholem Aleichem returned to Europe in 1908 and traveled the continent giving one-man performances, all while continuing to publish. He contracted the tuberculosis that would kill him, and was in and out of hospitals until well enough to return to New York in 1914. Worn out, distressed, and dependent on money from others, he moved to Harlem and then later to the Bronx.

After Rafael showed me a glass case filled with brochures, newspapers, and books penned by Sholem Aleichem, I left, wishing Rafael and his colleagues could find a bit more funding. God knows they could use it. And maybe a few less dolls.

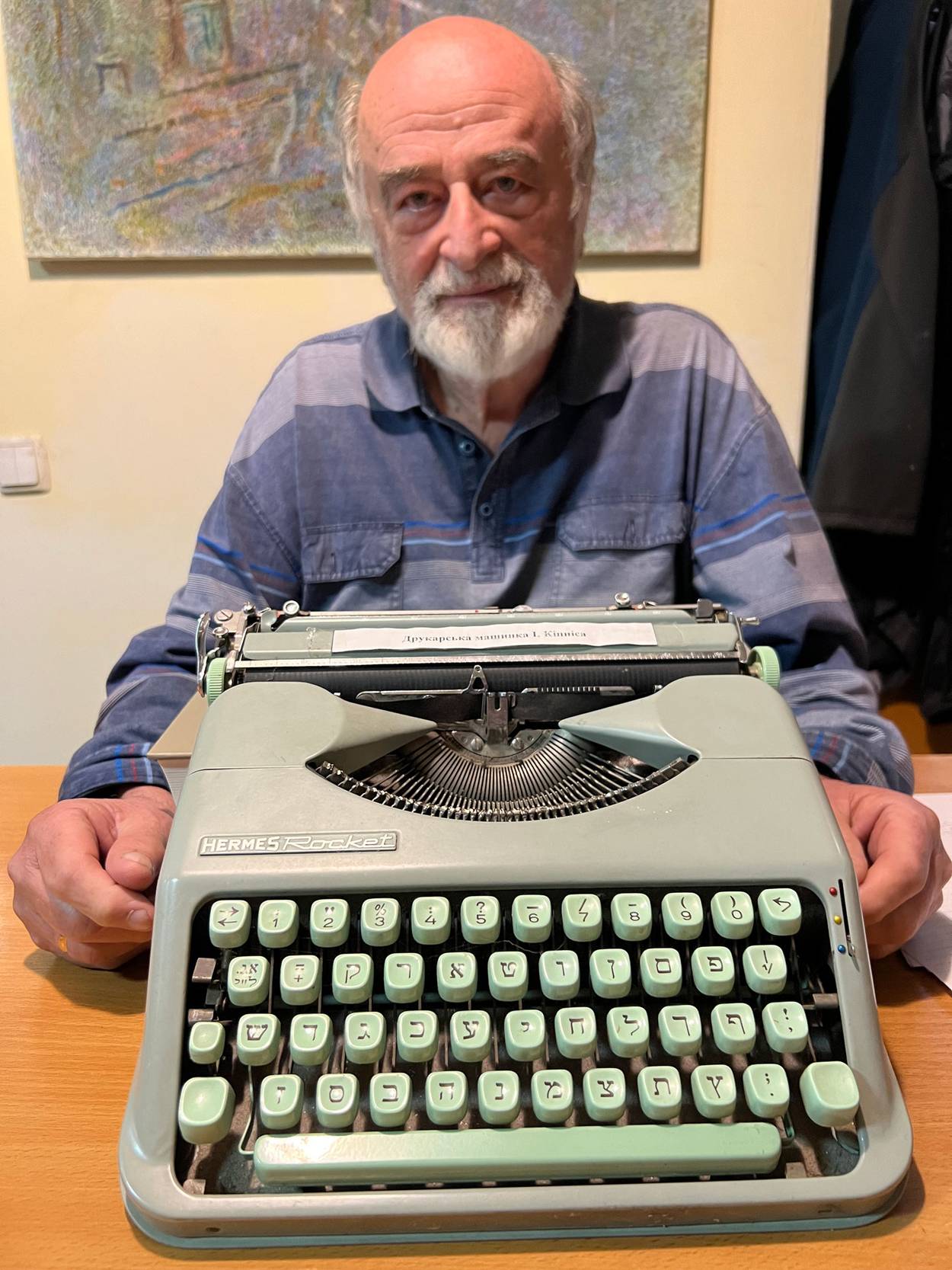

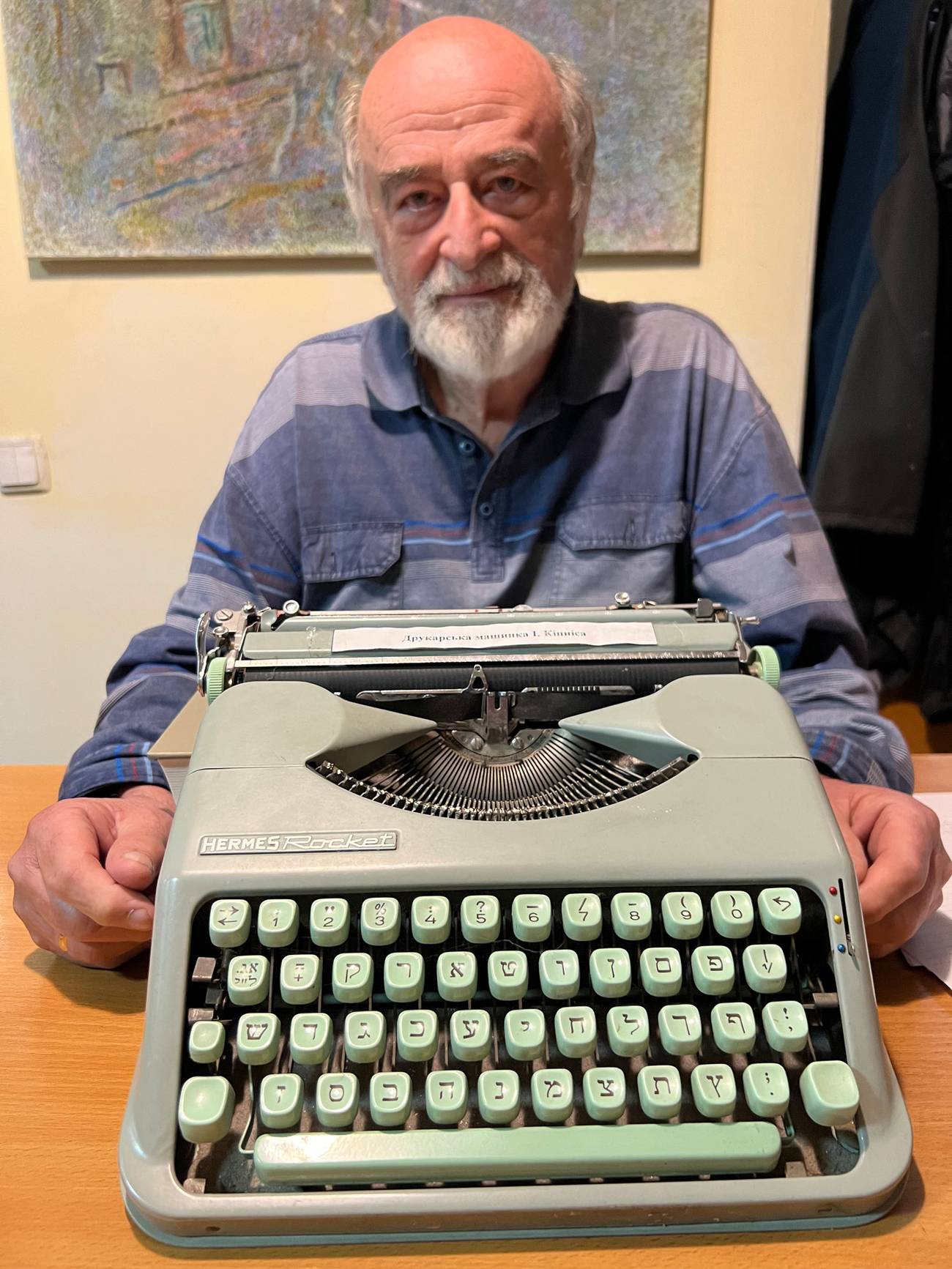

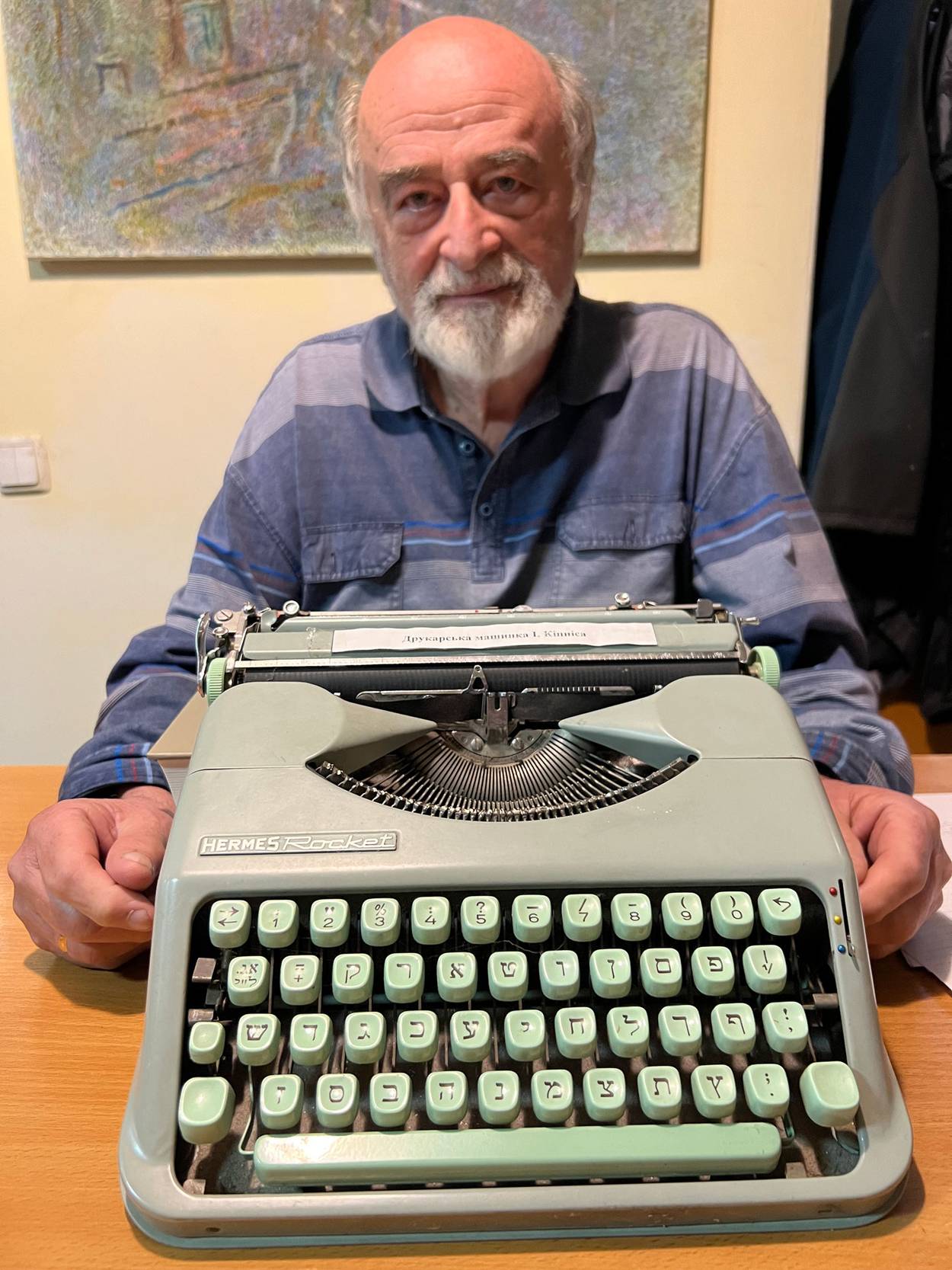

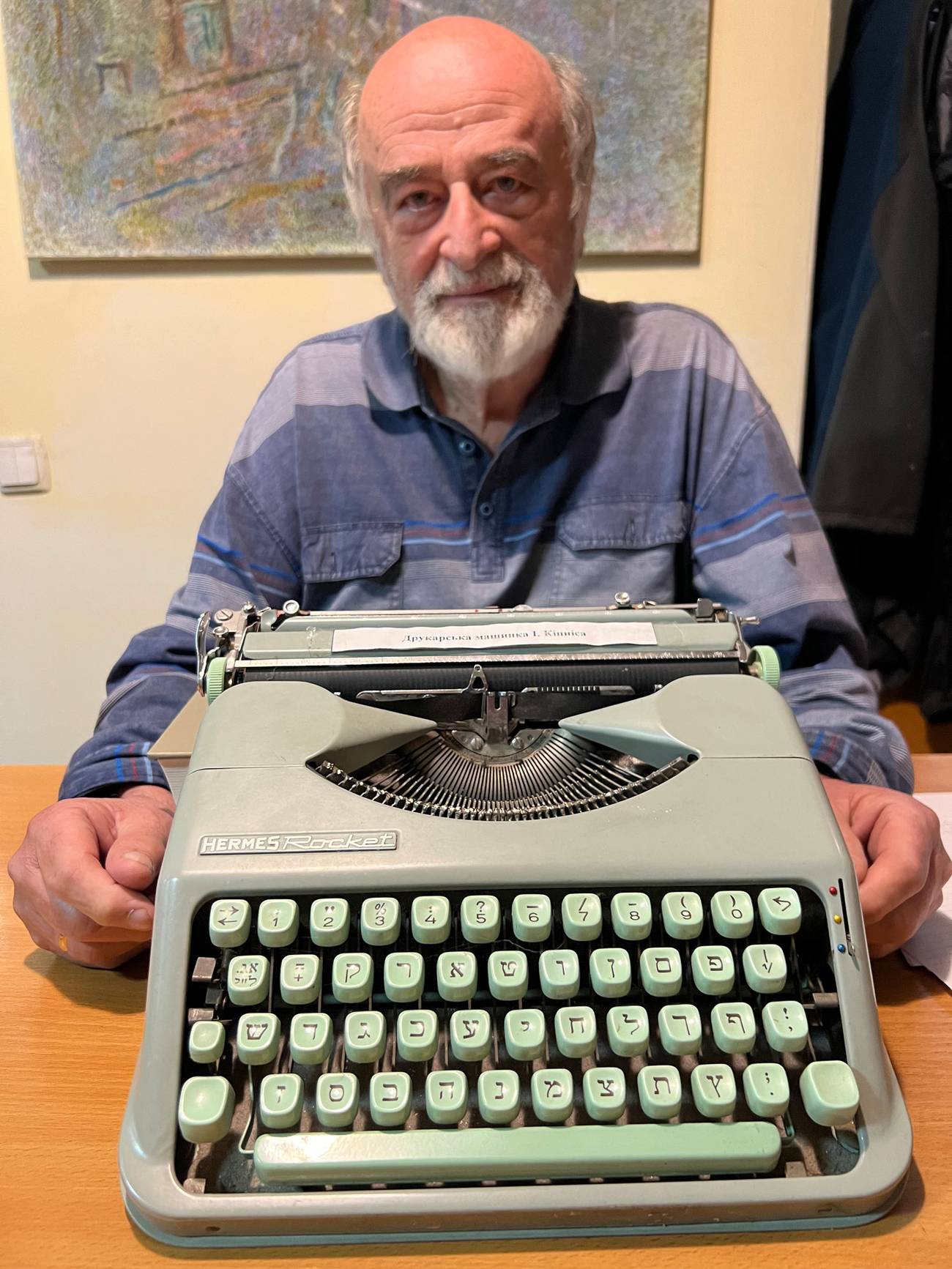

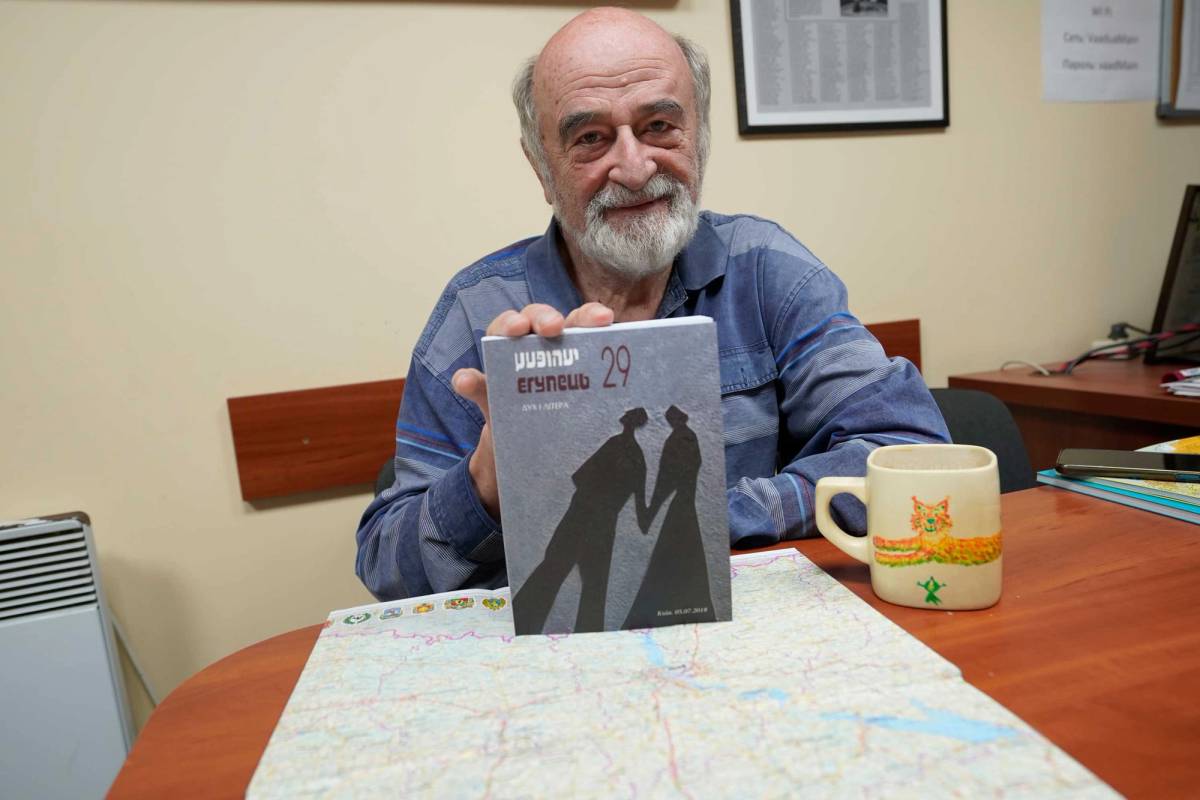

If it’s manual Hebrew typewriters you’re after, I have just the person to meet. I took the metro to the formerly Jewish, currently hipster neighborhood of Podil (Podol in Russian). I made my way into a warren of buildings by Kyiv University and into the basement offices of the Center Judaica, an organization with an archive of Ukrainian Jewish writers, a quirky collection of Ukrainian, Russian, and Hebrew language manual typewriters, and an incredibly productive publishing arm, including a highly respected annual publication, Yehupitz, Sholem Aleichem’s name for Kyiv.

The director is Leonid Finberg, a historian in his mid 70s who has been working on Jewish cultural projects even before the fall of communism and Ukraine’s independence in 1991. Leonid and I were joined by one of his Ph.D. students, Anna Umanska, whose doctoral work is on the Jewish Kultur-Lige in Ukraine, an institution that did not have a happy ending during the early years of Stalin’s reign.

Leonid said that Sholem Aleichem had been determined to establish a publishing company in Yiddish in the late 1880s. He began commissioning work from well-known writers, he was paying them handsomely, and he was publishing his own books as well as serialized pieces in Yiddish newspapers. And he strongly believed that Yiddish wasn’t just the language of poor Jews. It was a fine language for literature.

The problem was, even though most Jews spoke Yiddish among themselves, they bought their books in Russian and Hebrew. This helped sink Sholem Aleichem’s fortune.

Leonid said that despite his financial difficulties, Sholem Aleichem and Olga were still able to spend their summers in the resort town of Boyarka, not far from Kyiv, which he dubbed Boiborik in his fiction. This is where he met a man who delivered the family their milk every morning. Which got him thinking …

The first of the Tevye the Dairyman stories came out in 1894 and they would continue for nearly a decade. For those who have not read Hillel Halkin’s brilliant 1996 translation, they are well worth the investment of a few hours. And for those used to the schmaltz of Fiddler on the Roof, they will learn just how grim these stories actually were. It’s trademark Sholem Aleichem: part comedy, part tragedy. Often in a single paragraph.

Sholem Rabinovitch released his first story in Yiddish, ‘Two Stones,’ which he published with a new name: Sholem Aleichem, Hebrew for ‘how do you do.’ The name would stick.

Sholem Aleichem died in New York in May 1916 and less than two years later Russia withdrew from the First World War. Yet in his wildest nightmares, he could never have imagined that between 1918 and 1921, as Poles, Ukrainians, and Russians fought for control, perhaps as many as 100,000 Jews—and we are talking exclusively of unarmed Jewish families—would be slaughtered.

With most of Ukraine now in the Soviet Union, synagogues, like churches, were closed, many were destroyed, while Jewish schools could exist only if they taught nothing about religion or Hebrew.

In 1932 Stalin visited hell upon all Ukrainians during the Holodomor, the great famine, which killed between 3 million and 4 million Ukrainians, although some historians believe the number is far greater.

Then came the Second World War and the Holocaust. The number I have seen used most often is that between 1.5 million and 1.6 million Jews were murdered on the territory of current day Ukraine. The majority were shot by the Germans with the support and assistance of local Ukrainian auxiliaries.

As for Kyiv itself, the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum states that there were 160,000 Jews in Kyiv before the Germans invaded in June 1941, and around 100,000 fled eastward.

Perhaps as many as 60,000 Jews were in Kyiv on Sept. 26, 1941, when the Germans completed their occupation. They then summoned the city’s Jews to central collection points and three days later, on Sept. 29 and 30, 33,771 Jews were led to the vast ravine on the outside of town, Babi Yar (Babyn Yar in Ukrainian), where they were shot by the SS, German police units, and Ukrainian auxiliaries. Estimates are another 60,000 victims—Roma, Jews, communists—would be shot and dumped here before the Germans fled in December 1943.

Little wonder that historian Timothy Snyder dubbed this entire region as “the bloodlands.”

Courtesy the author

Part II: Katja Petrowskaja’s Kyiv

One of the most moving sections of Katja Petrowskaja’s Maybe Esther, translated into English by Shelley Frisch, comes when Petrowskaja asks her father what his grandmother’s name was.

‘I think her name was Esther,’ my father said. ‘Yes, maybe Esther. I had two grandmothers, and one of them was named Esther—exactly.’

‘What do you mean, “maybe”?’ I asked indignantly. ‘You don’t know what your grandmother’s name was?’

‘I never called her by name,’ my father replied. ‘I said Babushka, and my parents said Mother.’

Maybe Esther remained in Kiev. She had trouble getting around in the apartment, which was suddenly empty, and the neighbors brought her food. ‘We thought,’ my father added, ‘that we’d be back soon, but it took us seven years to return.’

The Kyiv that the Petrovskys and Finbergs returned to after the war was not the city they left. “During that first decade after the war,” Leonid Finberg’s mother, Lilya, said in a Centropa interview, “people did not like talking about the tragedy of the Jewish people. Words like ‘Babi Yar’ could only be whispered.”

Lilya Finberg went on to say, “The citizens of Kiev hated the Germans—I remember how they were hung on Kreschatik Street in the beginning of 1944, but their ‘love’ for the Jews was not great, either. I can’t comprehend this—after the tragedy in Babi Yar, the attitude toward Jews in Kiev was much worse than before it. This became especially obvious during the period of the ‘Doctors Trial.’ It seemed that traditional anti-Semitism was now enhanced by anti-Semitism ‘from above’—people simply would not go to Jewish doctors in Kiev.”

As we sat in Leonid’s office—in a neighborhood that had once been filled with Jewish families, schools and synagogues—he told me that in the postwar years, the only functioning Jewish institution in the whole of Kyiv was a synagogue just around the corner, the Choral Synagogue, and that it holds services to this day.

Courtesy the author

To paint a picture of what it was like following World War II, another Centropa interviewee, Peter Rabstevich, said “starting at Rosh Hashanah in 1944, thousands of people would stand on the street in front of the Choral Synagogue, which had been filled from the minute they opened the doors in the morning. So they wired up speakers and broadcast the service to those outside. It wasn’t kosher, of course, to use electricity like that on the High Holidays, but they did it anyway. I think two years later the authorities made them stop using the speakers. But still people came and they would completely fill the street. Most of them didn’t know how to pray, but they came out of solidarity, to pay tribute to their murdered families, and to remember that they were Jews.”

Leonid recalls the 1960s and ’70s in Kyiv: “it was almost impossible to go to Babyn Yar for the commemoration date. The police would block the streets, the buses wouldn’t run there. It was only during Perestroika in the mid 1980s, that we were finally able to hold a commemoration there.”

Rebuilding Jewish life after so many decades of Nazi destruction and communist repression was not easy. Ukraine’s first decade of independence, the 1990s, saw one economic catastrophe after another. The elderly were hit hard, but old Jews fared even worse, as they had almost no extended families left alive to care for them. Still, schools and synagogues set up shop and Chabad has played an outsize role, while the Claims Conference and the Joint Distribution Committee help with the elderly and with social programs. The ORT school in Kyiv, which is as secular as Chabad schools are observant, sees over 1,500 students every day, although during the war, around 500 attend classes online from abroad or from the west of the country.

Leonid’s organization began training academics in the early 1990s and publishing Yehupitz, which his friend Miron Petrovsky advised on. Well more than 150 M.A. students have gone through programs with Leonid and other professors, and the center has recently translated two books by Hannah Arendt, Alexandra Popoff’s biography of Vasily Grossman, four different biographies and studies of Bruno Schulz, and a new book, written by Leonid’s colleagues, on the Beilis trial. And all of this during Russia’s full-scale invasion.

It is this period of Jewish life in postwar Ukraine that Katja Petrowskaja captures in her work. Petrowskaja studied Slavic studies and literature in Estonia, conducted graduate studies at Stanford and Columbia, and then received her doctorate in Moscow. She married, moved to Berlin, and began a family of her own.

She wrote for several of Germany’s and Switzerland’s most prestigious newspapers while researching Maybe Esther, which has been likened to the work of W.G. Sebald and of which, writing in The New Yorker, Masha Gessen said: “The book is breaking my heart, because I want to stop and quote from every other paragraph, and I want to give copies to people I love.”

With all its turns, travels and digressions, Maybe Esther isn’t quite a family chronicle, although, cumulatively, that is where it takes you in its 70 short chapters.

And Gessen is right; there are barbs, ironies, and insights on every page. “History begins when there are no more people to ask,” for example. As I walked past the Choral Synagogue, I tried to envision what this empty street would have looked like filled with thousands and thousands of Jews, every one of whom must have lost someone, or many someones, at the front or in ravines. And I sighed, thinking that only a handful of the 278 elderly Ukrainian Jews my institute interviewed are still alive, still able to share their stories.

So yes, I’d say Petrowskaja has it just about right.

Edward Serotta is a journalist, photographer and filmmaker specializing in Jewish life in Central and Eastern Europe. He is the head of the Vienna-based institute Centropa.