Moral Cruelty and the Left

The late scholar Judith Shklar warned that liberalism can degenerate into a cult of victimhood that permits our sadistic desires to be passed off as unimpeachable virtue. Her warning is newly urgent today.

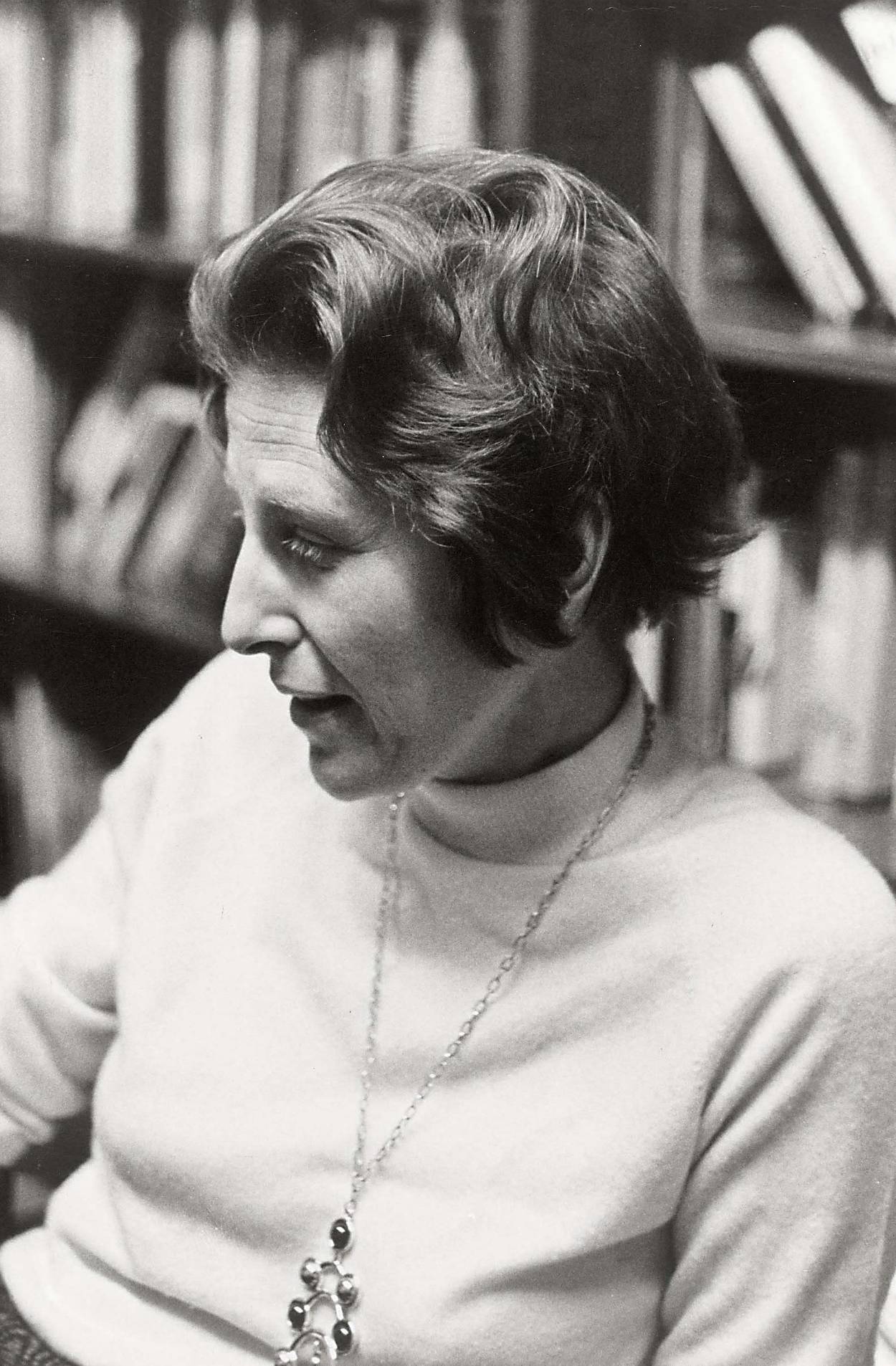

“To be alive is to be afraid,” Judith Shklar declared in her 1989 essay, “The Liberalism of Fear.” Since her death in 1992, it has become a key text in contemporary political theory, and its author the subject of a growing field of Shklar Studies. Shklar is best known as a defender of the American political tradition against radicalisms of the right and left, and “Liberalism of Fear” provides a compelling justification for our system of limited and democratic government as the best means of protecting us from “physical cruelty” perpetrated by agents of the state. But cruelty is far more complicated than it might appear. Those who fight to eliminate the obvious cruelty of brutality and violence can be no less cruel in their own subtle and sinister ways.

In her brilliant book Ordinary Vices, published five years before “Liberalism of Fear,” Shklar argued that we need to be afraid not only of physical cruelty committed by officials and police, but of the “moral cruelty” committed by those who claim to hate oppression. Drawing on the ideas of Friedrich Nietzsche—whom she considered one of the most dangerous enemies of liberal democracy—Shklar warned that liberalism can degenerate into a cult of victimhood that permits our sadistic desires to be passed off as unimpeachable virtue. As the United States is confronted with (often violent) protests against police violence and an increasingly strident and intolerant political culture of racial “wokeness,” Shklar’s argument that liberalism is endangered by both physical and moral cruelty is of urgent relevance. We have much to fear.

Born into a family of German-speaking Jews in Riga, Latvia, in 1928, Shklar learned fear early in life. At the age of 11 she and her family fled the coming Soviet invasion to Canada. Had she not escaped, she would have almost certainly died in the subsequent German invasion and occupation that killed more than 94% of Latvian Jews. The rest of her life was relatively sedate: a bachelor’s degree at McGill (1949), a Ph.D. (1955), and then a job at Harvard’s Government Department (1956-1992). But four decades of stability in Cambridge did not dull what that childhood experience of vulnerability had taught her.

Shklar insisted in “Liberalism of Fear” that the danger of totalitarian regimes driven by radical ideologies still hung over Western societies. Worse, our usual injunctions to remember those regimes often seem powerless to stop political violence in the present: “We say ‘never again’ but someone somewhere is being tortured right now.” Liberalism, Shklar argued, is our best hope against these dangers—but there is always the risk that our politics may degenerate into authoritarianism or the intonation of ineffectual pieties. We must look, and keep looking, into those parts of ourselves that might desire or permit the return of the worst forms of unfreedom. We must be particularly vigilant, she warned, against the vice of cruelty.

“Liberalism of Fear” outlines a justification of the American system of government as the best means of resisting this vice, of which authoritarian regimes are the most obvious manifestations. With political power divided among multiple branches, subject to democratic controls, and contested by a liberty-loving public, our regime has several lines of defense against authoritarianism. But, as Shklar noted, any time we fear arbitrary “physical suffering” at the hands of agents of the state, we face the summum malum of cruelty, this worst of evils. If we are vigilant against a return of fascism and not against murderous police officers, our liberalism is not worth much.

Shklar’s project is apparently straightforward. A closer consideration of her thoughts elsewhere on the subject of cruelty, however, reveals disorienting paradoxes. In Ordinary Vices, as in the later “Liberalism of Fear,” Shklar argued that liberals should see cruelty as the greatest of evils. But cruelty does not appear only in the form of physical violence, and is not committed only by the state. Shklar suggested that liberalism may be destroyed from within by liberals’ well-intentioned efforts to eradicate cruelty.

In Ordinary Vices, Shklar took up two insights from Nietzsche. First, our fear of physical cruelty is not natural or self-evident, but the product of a particular set of historical contingencies. The modern West’s feeling of “horror” toward the bodily suffering of others is something unique in the history of the world. Inhabitants of ancient Rome, with its gladiatorial games, or the Aztecs, with their human sacrifices, reveled in cruelty that shocks and outrages us.

Our sense that all human beings are endowed with moral worth that ought not to be degraded, especially by inflicting pain, appeared to Shklar, and to Nietzsche, as the product of our peculiar religious heritage. Shklar argued that Christianity had taught Western cultures to value compassion and feel with those who suffer—but only in an “ex-Christian” and secular society can these values become paramount. Fear of cruelty to human beings can only be the worst vice for people who no longer fear God but have been enduringly shaped by their historical encounter with religion.

The other key insight Shklar found in Nietzsche is that fear of “physical cruelty” can be transformed into “moral cruelty” by “deliberate and persistent humiliation, so that the victim can eventually trust neither himself nor anyone else.” Those who see themselves as fighting against physical cruelty, from Christian priests railing against the iniquities of the Roman Coliseum to their distant descendants, the social justice warriors of today, can inflict all kinds of psychological torment on their opponents—and themselves.

Nietzsche saw Christianity and the post-Christian ideologies of liberalism, socialism, etc. as mechanisms of humiliation by which people were made to feel guilty, sinful, and self-doubting. These moral systems associate every moral quality that might lead to physical cruelty—aggression, confidence, vitality—with evil. They pathologize strength and sanctify weakness. In this way they cripple and deform the psyches of the noblest sort of people, those who are overflowing with power and desire. At the same time they allow self-described victims to pursue cruel vengeances against their supposed oppressors. They preach masochism to the strong and sadism to the weak.

If one is really sensitive to cruelty, Nietzsche suggested, then one must reject the moral cruelty that lurks behind campaigns to eradicate physical cruelty. One must rescue people from the humiliation and loss of confidence that Christianity and its political heirs impose. Shklar took this paradox seriously. In a Nietzschean reading of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s novel The Scarlet Letter, she analyzed the ways that Christianity, ostensibly opposed to cruelty, can lead believers to inflict suffering on others and themselves. A “humanitarianism unshaken by skepticism and unmindful of its limitations,” she concluded, can indeed be crueler than more obvious and brutal forms of violence it seeks to resist.

Shklar did not provide present-day examples of moral cruelty, preferring to stay with the safely nonpolitical example of a 19th-century allegory about 17th-century Puritans. We cannot afford such detachment. Everywhere around us, people are acting cruelly in the name of eradicating physical harm and arbitrary power. Anyone working in a university, cultural institution, or large corporation today has spent recent weeks reading emails, attending meetings, and participating in conversations that are theaters of moral cruelty. White people in such contexts are asked—or required—to admit that they are culpable, that they lack ethical and epistemic authority, that they must listen to and heed the demands of victims of racism. They humiliate themselves, literally kneeling in propitiation.

Shklar found such acts of self-debasement no less cruel and terrifying than the violence that they are supposedly meant to resist. Healthy minded people, she urged, do not want to suffer in this way—nor do they want to attain power and self-respect at the cost of presenting themselves as a “model of moral victimhood.” As she considered the self-torturing Puritans of Hawthorne’s novel, she acknowledged that Nietzsche was on to something in his diagnosis that Western modernity had learned “too well” how to fear physical cruelty and pity its victims: “towards others one felt only pity, because thanks to a humiliating religion everyone could identity instantly with suffering and victimhood.” The legacy of Christianity is a morally poisonous fear that makes decent people unable to respect themselves or resist demands made by victims.

Nietzsche’s solution, as Shklar described it, was to refuse moral cruelty and accept physical cruelty. Let victims suffer, let the weak perish, so that the strong can enjoy a clear conscience free of the lacerations of guilt. Shklar warned that the “megalomaniacs of interwar Europe,” Hitler and Stalin, learned this lesson from Nietzsche. There was, in her account, a clear line from his critique of moral cruelty to the totalitarian regimes that had destroyed the world of her childhood and nearly killed her. But this was not a reason to dismiss his critique. Defending liberal democracy, Shklar claimed, will require us to confront Nietzsche’s powerful argument against the moral cruelty that liberalism seems to generate from within its post-Christian heritage. Otherwise, intelligent people who refuse to reduce themselves to cringing sinners will turn to the Nietzscheanisms of the radical left and right. Liberals must not make decent people choose between liberalism and self-respect.

“Liberalism of Fear” does not address this difficult problem, or even acknowledge the frightening possibility that our concern for physical cruelty might lead us to inflict moral cruelty. Perhaps Nietzsche’s insights are not always seasonable. Certainly they seem to destabilize any coherent project for defending our regime such as the one offered in “Liberalism of Fear.” Shklar posited the latter as a straightforward project, a sketch of an apology for the American political order, while she saw Ordinary Vices, as a “tour of perplexities, not a guide for the perplexed.”

Perhaps what we need is a guide to being perplexed. Liberals, Shklar suggested, must maintain a condition of earnest perplexity, of skepticism toward what seems virtuous and concern about the multiple, contradictory dangers that we face. For liberalism to survive, Shklar warned, we will have to maintain a sharp-eyed fear not only of physical violence on the part of the state, but also the spiritual perversions of today’s Puritans. We must be afraid, above all, that our disgust with these cruelties may lead us to abandon the moral life entirely, beckoning a new barbarism. To fear and fight these three dangers all at once will not be easy. Indeed, Shklar acknowledged, “liberalism imposes extraordinary ethical difficulties” by requiring us to fight on so many fronts, to accept perplexity as a constant condition, to fear the subtle transformations by which virtues become vices and victims become torturers. But “no one has ever promised us an effortless moral life.”

It may seem that our form of government is not conducive to the moral life on which its survival depends. Liberal democracies are not good places to find good people, Shklar warned. Their citizens are habituated into “self-assertive vices” of acquisitiveness, selfishness, and cowardice. But only in a free society can people have any opportunity for developing an ethical character, without having to bow before the “pious cruelties” and “massive dishonesty” of regimes that impose a vision of the common good on their inhabitants. Provided, that is, our characters are not warped by the moral cruelty of liberalism’s misguided humanitarians.

Blake Smith, a contributing writer at Tablet, lives in Chicago.