Martyrologies

Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish created a poetry of martyrdom for his people—and a political coup for the idea of the nakba

A poem is bound by language but a poetics is not. But what is a poetics? Is it a style or mood? Is it a question or answer? Or is searching for a definition for this enigmatic term akin to the infamous search for a word meaning “a word without synonyms”? Aristotle, by defining poetics as the theory of making art out of words, partitioned it from rhetoric, which he defined as the theory of turning words to governance, to politics. Though the poetic has always engaged with the political, in our day the political has ceased engaging with the poetic: Though the Soviet Union is no more and Mandelstam and Tsvetaeva are still read, and though ancient Greek and Latin are no longer spoken and Pindar and Virgil are still read, there is no doubt that what will survive today’s regimes will not be verse so much as verselike caches of random data.

Synonyms are both logical fallacies—no two words can be identical—and artistically useful (expedient, practical); synonymic poetics furthers that paradox into history, or histories. Which is to say that though the genres of tragedy and comedy transcend borders, races, and creeds, specific tragedies and comedies do not. The event one people celebrate with a victorious ode another people commemorate with an elegy of defeat.

Poetry that’s old enough, that has justified its age, tends to be credited to that greatest of versifiers, “Anonymous.” Let’s summon that God, for a moment, to bless the following scraps, translated into the neutrality of English:

How will you fill your cup

On the day of liberation? and with what?

Are you prepared, in your joy, to endure

The dark howling heard

From skulls of days glittering

In a bottomless pit?

And:

We survived much death. We defeated forgetfulness and you said to me: We survive, but do not triumph. I said to you: Survival is the prey’s potential triumph over the hunter. Steadfastness is survival and survival is the beginning of existence. We persevered and much blood flowed on the coasts and in the deserts. Much more blood than what the name needed for its identity, or what identity needed for its name.

The first fragment is a stanza from How? written in 1943 in the Vilna Ghetto by the Yiddish poet Abraham Sutzkever. The second is from In the Presence of Absence, one of the last collections of stray sentences in paragraphs by Mahmoud Darwish, perhaps the foremost Palestinian poet of last century (published in Arabic in 2006, and this month by Archipelago Books, in a translation by Sinan Antoon).

That these two texts spring from a shared poetics can be denied only by those who read prejudicially, who judge books by covers of their own creation: When you oppress a people, when you beat and rape and kill them, the literature they write will inevitably resemble the literatures of other peoples who’ve been beaten, raped, and murdered (unless you’ve stumbled upon a happy tribe of masochists). But this shock must be admitted: The same poetics has sadly marked the literatures of Jews—not just Israelis—and Palestinians, in the same century—a poetics that fled Europe and hid, until it found another shelter.

***

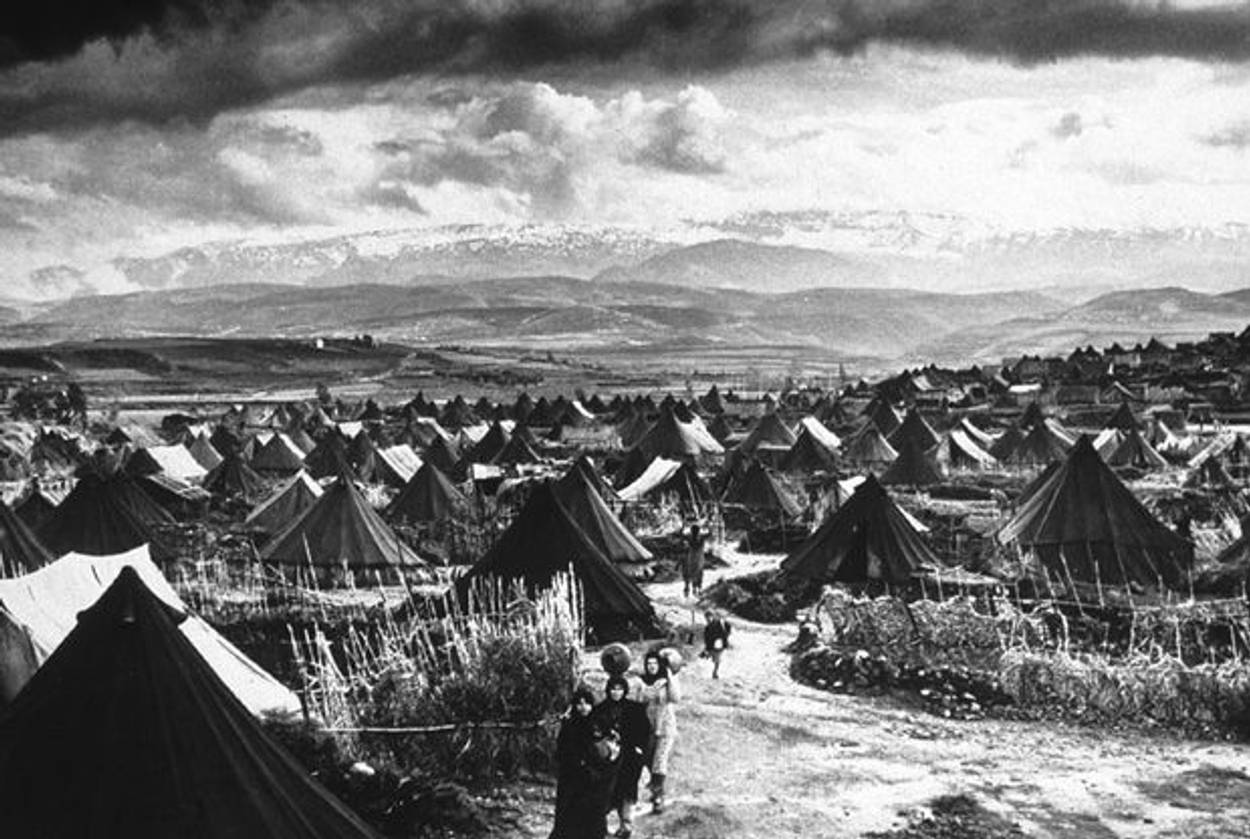

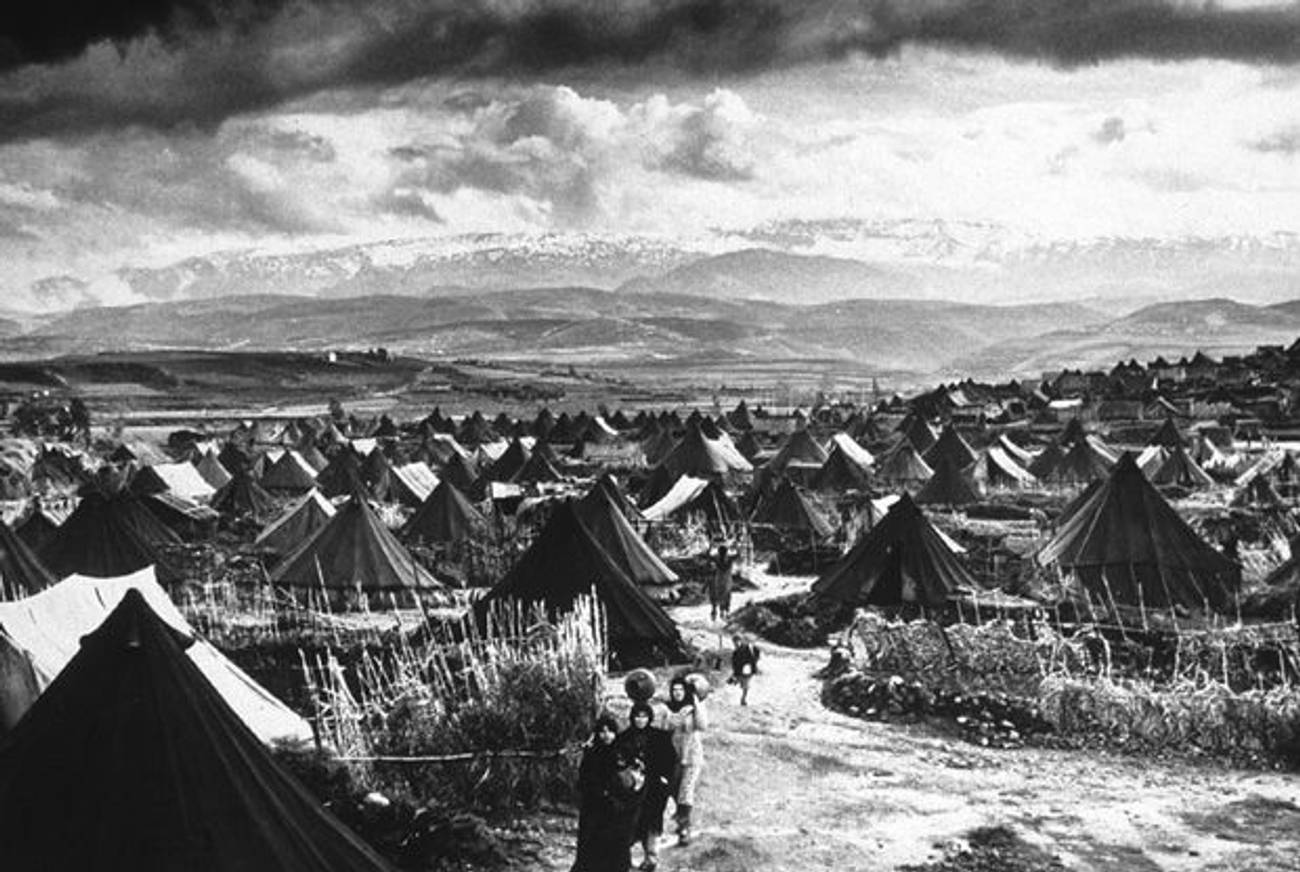

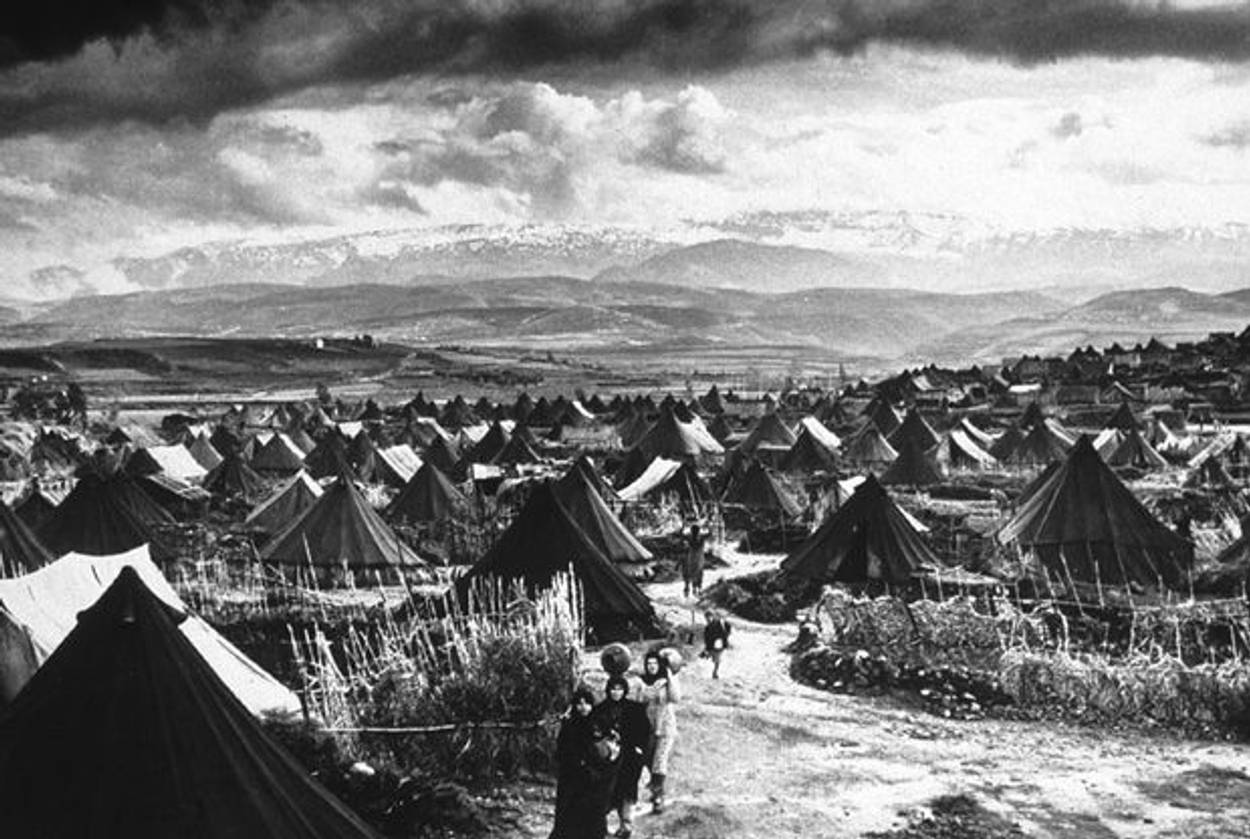

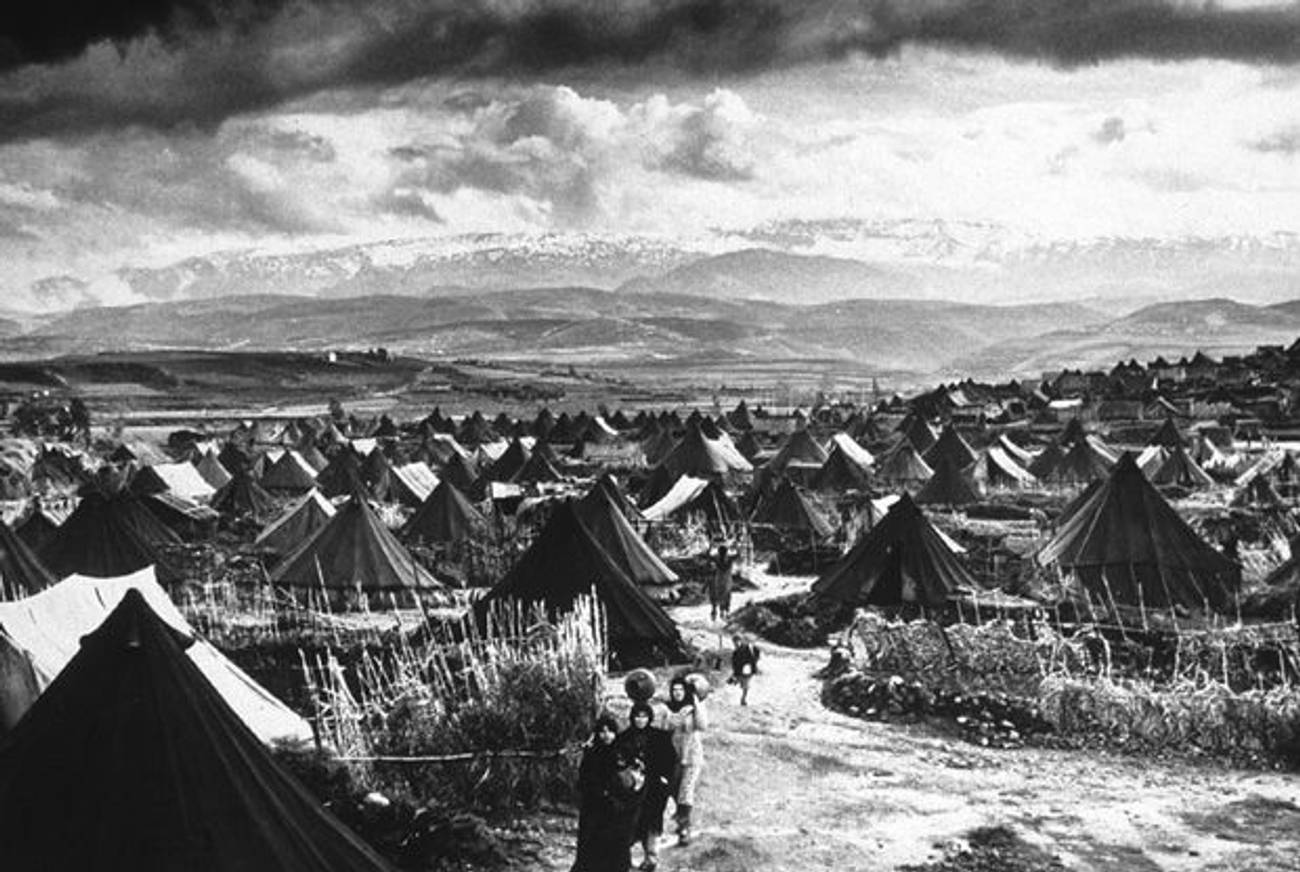

Al-Birwa was a tiny olive, grain, and watermelon village in Western Galilee, Mandate Palestine. Darwish was born there to a Sunni Muslim family in March 1941, the same month and year the Nazis’ extermination camps became fully operational. In 1948, with war ended, war began: Darwish’s family was forced from their orchards by the nascent IDF’s Carmeli Brigade; they fled to Lebanon, to Jezzine and Damour. Later, they illegally returned to Israel—insofar as one can return to a different country—settling in Deir al-Asad, which had been renamed, in Hebrew, Shagur. (Darwish spoke fluent Hebrew.)

In 1970, Darwish, then a communist, briefly attended university in Moscow before migrating to Egypt and then to Lebanon again. There he joined the PLO, for which he coauthored the Algiers Declaration. When the PLO was expelled from Lebanon, Darwish went to Cyprus. Stints followed in Tunis and Paris. For his work in the PLO, the poet was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize, originally the Stalin Peace Prize, which he accepted as idealistically as he’d later reject the Oslo Accords (which occasioned his break with Yasser Arafat).

It was Oslo, however, in its slight easing of restrictions in the Occupied Territories, that gave Darwish a temporary reprieve: In 1996, now a poet with an international reputation and a major cardiac condition, he finally received Israeli permission to settle in Ramallah. Throughout the 1980s and ’90s, major infarcts had led to major surgeries. Though his literary heart was strong, his literal heart was weak—so went the global obituaries. In August 2008, while undergoing treatment at a hospital in Houston, he died. He’s buried in Ramallah, atop a hill called Al-Rabweh, “the hill of green grass”—a small snatch of his childhood Galilee transported to the dusty West Bank.

So do not reconcile with anything except for this obscure reason. Do not regret a war that ripened you just as August ripens pomegranates on the slopes of stolen mountains. For there is no other hell waiting for you. What once was yours is now against you.

And:

I am already quite scarce. For years

appearing only here and there

at the edges of jungle. My awkward body,

camouflaged by reeds, clings

to the damp shadow around it.

Had I been civilized,

I would never have been able to withstand.

I am tired. Only the great fires

still drive me from hiding to hiding.

Let’s avoid turning this survey into an exercise in perversity, a childish game: I’ve chosen to quote Darwish in his prose-poems, and the others, the original Others, enjambed. The man “already quite scarce” is the Israeli poet Dan Pagis. The source for the excerpt above is a poem called The Last Ones. The initial circumstance is the language, then the name and title, and only then, the poem. Bad poetry wants for forewords, good poetry, for afterwords, whereas Pagis’ poetry, like Darwish’s, needs a more encompassing apparatus—it necessitates experience.

To read this poetry truly, one would’ve had to have written it—to have been born, as Pagis was, in Bukovina in 1930 (Bukovina was also the birthplace of Paul Celan); to have spent an early adolescence in forced-labor camps in Transnistria; to have emigrated to Israel in 1946, speaking nothing but crusts of Yiddish, Romanian, Russian, and a German poisoned by Nazism, and yet, within two decades, to have become one of the great scholars of medieval and Renaissance Hebrew. This biographical recitation won’t end with death, however (which came for Pagis in 1986), but with the reminder that nothing that’s been recounted has altered even a single word of the poem that precedes—Pagis, like Darwish, remains “uncivilized.”

The more we’re aware of martyred authorship the more our readings tend to fall into that “jungle” between the “mountains”—halfway between appreciating the art and being awed by the witness. Certainly the process of separating the aesthetic from the evidentiary cannot be as primitive as, say, determining citizenship—art cannot be fixed in time like the 1940s, nor fixed in space like Gaza, or like an Auschwitz-Birkenau Appelplatz. Studying a martyr’s poetry is the secular equivalent of studying the Bible: Some come for the truth and stay for the beauty; others come for the beauty and stay for the truth.

One wool sweater alone is not enough to befriend the winter. You will look for warmth in your books, escaping the mire into an imagined world, ink on paper. And songs you could only hear from the neighbors’ radio. Dreams would not find room in a mud house, hastily built like a chicken coop with seven dreamers crowded inside—none of whom would call the others by name since names had become numbers. Speech, dry gestures to be exchanged only when absolutely necessary, such as when you lose consciousness from malnutrition and are treated with fish oil, the civilized world’s gift to those driven out of their homes. You are forced to drink it, just as you force pain to swallow its voice by feigning contentment.

This pan-Semitic poetics I’m attempting to describe is synoptic, and territorially insatiable, annexing both the authority and the authorial liberties of scripture and commentary. It was Darwish’s brilliant conceit to create a late poetry of martyrdom that reads as an addendum to, and gloss on, all the martyrologies that came before it. It’s not that the surfeit of suffering to be found in the literature of 20th-century Jewry was Darwish’s subject, rather that that literature became, by a conversion that was as much a usurpation, his primary text—the gray ur-poetry to be appropriated, and revised, by the Palestinians’ more immediate trauma. (In the process, imagery remained intact: trees, stones, blood; only proper nouns and landscapes differed: Darwish gave us deserts, prisons, forts by seas, Jericho.)

Of course, the poets of the Holocaust themselves sourced from earlier poetries of affliction: Yiddish poets in particular rendered the archaic laments of Hebrew and Aramaic into a living European idiom. Kalonymus ben Judah’s “Oh that my head were waters, and mine eyes a fountain of tears,” written in the Rhineland following the slaughter of the First Crusade, was an adaptation of a stanza from the Book of Jeremiah. Psalm 137’s “waters of Babylon” have been fluenced, by obvious metaphor, into every age’s Rhine, and Vistula—and Jordan.

(Dahlia Ravikovitch, a native Israeli of Darwish’s generation, ruthlessly evoked this Psalm in her 1986 poem, You Can’t Kill A Baby Twice:

By the sewage puddles of Sabra and Shatila,

there you transported human beings

in impressive quantity

from the world of the living to the world

of everlasting light.)

To absorb this tradition, Darwish had to deny its parochialism: He accused his oppressors by recalling their oppressors, the enemies of his enemy who were never his “friends.” After having assimilated the Russians and Surrealists, Apollinaire, Mallarmé, Verlaine, Rimbaud, Avicenna, and the classical Arabic court poets—not to neglect Muhammad, who received the Quran from the Angel Gabriel, who himself was but the amanuensis of Allah—would it be so strange for Darwish, long in a short life, to have found his best models here, among the Jewish poets—their corpora of corpses? His words raised the words of the dead at Metz, Speyer, Worms, Mainz, Cologne, at Belzec and Treblinka, into warnings to their modern descendants; he rewrote the Deuteronomic injunction, “remember,” to refer to the present: Look, See, Hear, Listen.

It’s only now, with Jewish literature cleaving to either American pieties or Israeli anomie, that Darwish’s stunning poetics can be revealed—through the sheer egality of its referents—as a political coup: Because of his poetry, the Holocaust and al-nakba, the destruction—as the Palestinians call the founding of Israel—can now be compared. Not in the numbers of the victims, neither in the intentions of the victimizers—rather in how the individual human howl is, and will be, worded.

And so much blood flowed that tracking blood, our blood, became the enemy’s reassuring guide, afraid of what he had done to us, not of what we might do to him. We, who have no existence in “the Promised Land,” became the ghost of the murdered who haunted the killer in both wakefulness and sleep, and the realm in-between, leaving him troubled and despondent. The insomniac screams: Have they not died yet? No, because the ghost reaches the age of being weaned, then comes adulthood, resistance, and return. Airplanes pursue the ghost in the air. Tanks pursue the ghost on land. Submarines pursue the ghost in the sea. The ghost grows up and occupies the killer’s consciousness until it drives him insane.

Joshua Cohen was born in 1980 in Atlantic City. He has written novels (Book of Numbers), short fiction (Four New Messages), and nonfiction for The New York Times, Harper’s Magazine, London Review of Books, The Forward, n+1, and others. His first essay collection, Attention: Dispatches from a Land of Distraction, will be released in August. In 2017 he was named one of Granta’s Best of Young American Novelists. He lives in New York City.

Joshua Cohen was born in 1980 in Atlantic City. He has written novels (Book of Numbers), short fiction (Four New Messages), and nonfiction for The New York Times, Harper’s Magazine, London Review of Books, The Forward, n+1, and others. He is the recipient of the 2022 Pulitzer Prize in fiction, for The Netanyahus: An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family. He lives in New York City.