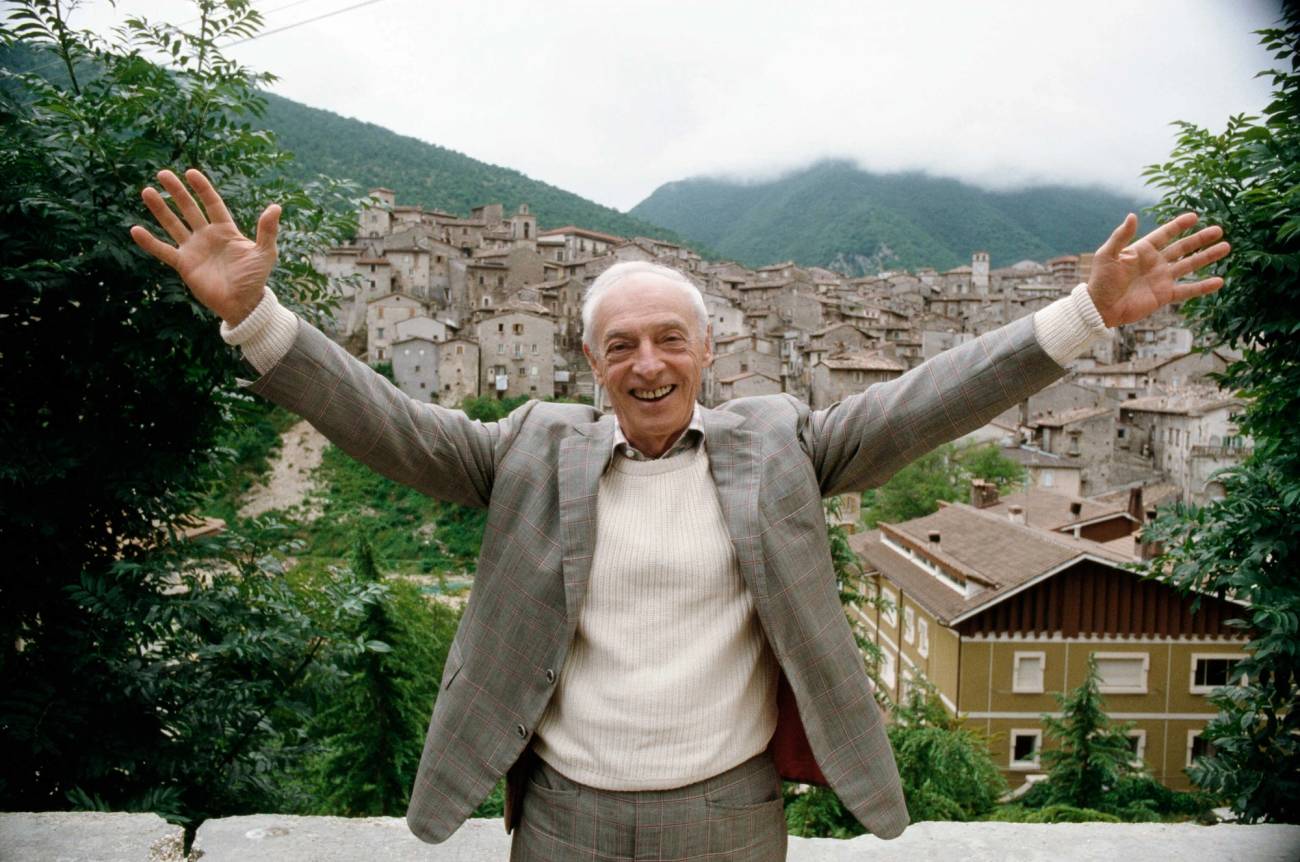

God, How We Miss Saul Bellow

Nearly 20 years after the great Jewish and American novelist’s death, we have never been more in need of his thirst for life

Alberto Roveri/Mondadori via Getty Image

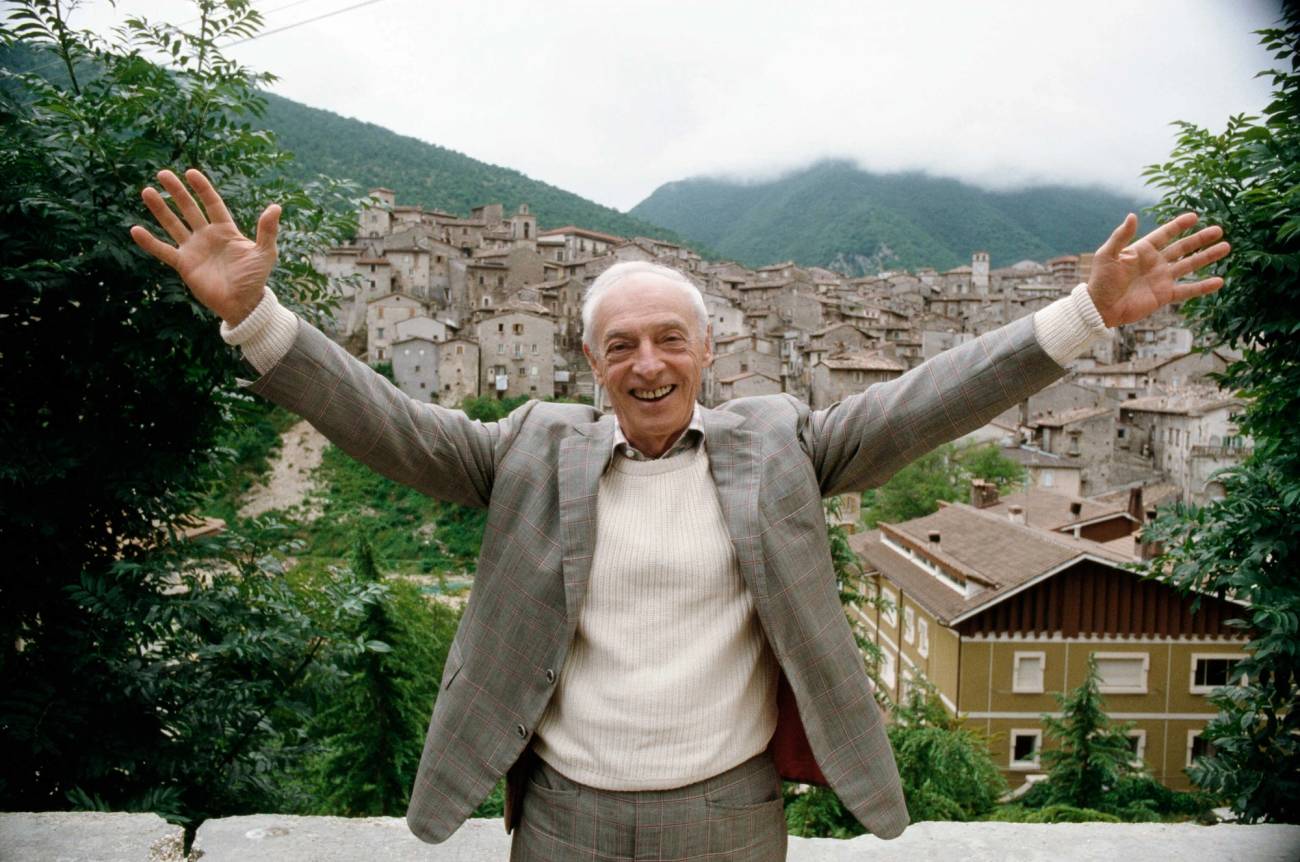

Alberto Roveri/Mondadori via Getty Image

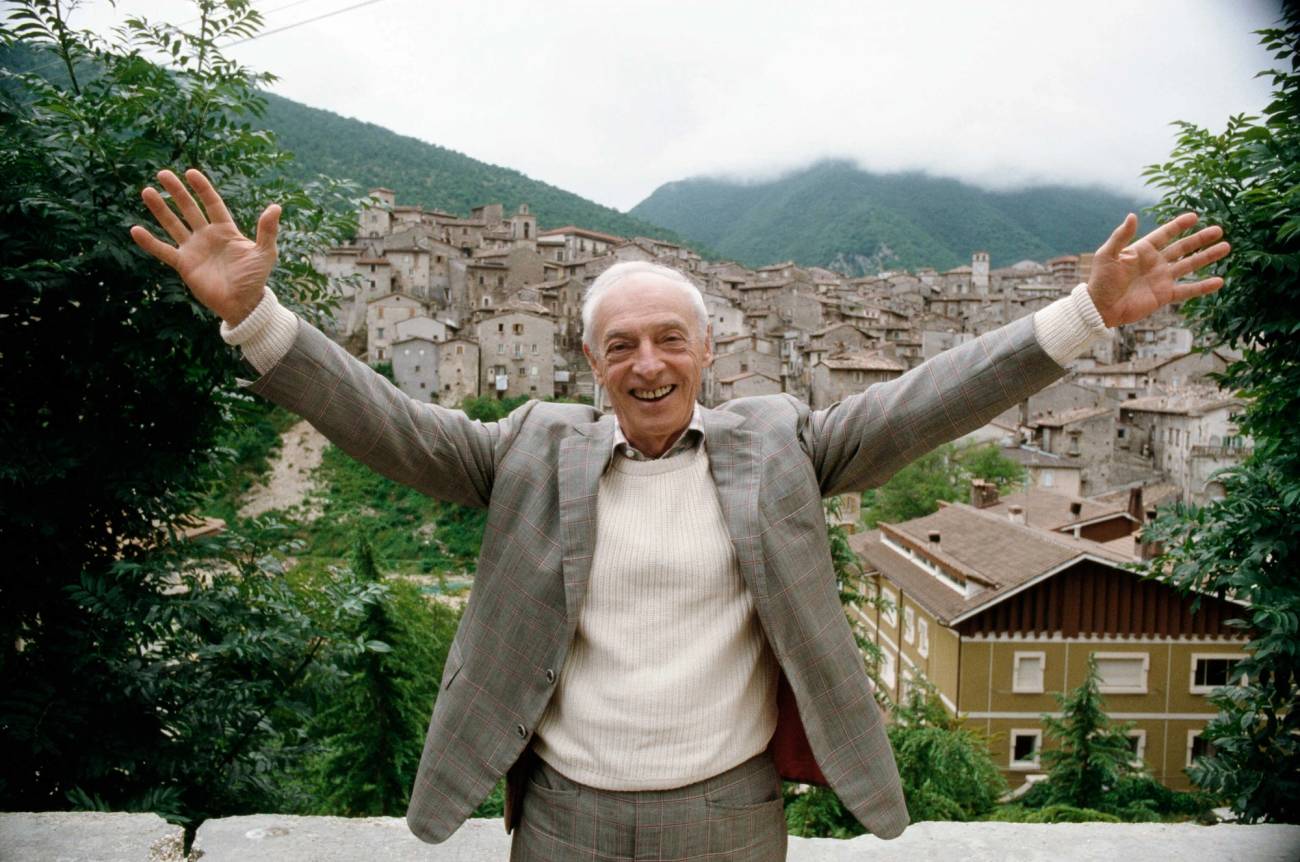

Alberto Roveri/Mondadori via Getty Image

Saul Bellow, who passed away this day in 2005, once the most celebrated of late-20th-century American writers, is now barely taught in universities, disdained as an out-of-date fogey with, we are told, conservative-adjacent hang-ups. But readers will always return to Bellow. Every so often I meet people whose faces light up when they discover I have written about him. Bellow, they tell me, lifted them out of the doldrums and into the clouds. Bellow’s tenacious desire for more life, passed on so readily to readers, never disappoints, and so it will never be lost to a discerning reading public.

Gerald Sorin’s new biography, Saul Bellow, draws its subtitle from a Bellow interview: “I was a Jew and an American and a writer.” Chronologically, the sentence holds true. Bellow, who was born in Lachine, Quebec, in 1915 to a Yiddish-speaking household, was a Jew before he became an American. When he was 8 the family moved to Chicago, where his father was a bootlegger and also ran a coal yard. Bellow’s writing career was scorned by his father and brothers, who saw him, Saul said, as a “schmuck with a pen.” What he should have been was a money Jew, a businessman like his elder brother Maury, who rubbed elbows with gangsters.

“To be a Jew in the twentieth century / Is to be offered a gift,” the poet Muriel Rukeyser wrote in 1944 (lines that Sorin uses for his epigraph). Rukeyser produced this sentence during the most disastrous year for Jews in all of history. Yet she saw Jewishness as a gift rather than a curse, even in the midst of the Shoah, that black cloud of doom. So did Bellow, who published his first novel, Dangling Man, that same year.

Sorin says accurately that Bellow’s Jewishness was the germ of his being. Being born Jewish, Bellow once remarked, was “a piece of good fortune with which one doesn’t quarrel.” These days Jewishness is often seen as obligatory, an all-too-serious matter. For Bellow, it was a pleasurable stroke of luck.

Yet “when people call you a ‘Jewish writer’ it’s a way of setting you aside,” Bellow added. He stridently opposed Jewish schmaltz and the hawking of folkloric wares and shtetl nostalgia. Jewishness was about being an intellectual or a macher. Bellow thrived on the high-wire arguments of the Partisan Review crowd, including his doomed friend Delmore Schwartz, whom he memorialized as Von Humboldt Fleisher in Humboldt’s Gift. Humboldt had the heiresses of Henry James down cold, and he could talk for hours about the Rockefellers, Harry Thaw, and Evelyn Nesbit, modern poetry, opera, and baseball. At the end of his writing career Bellow paid tribute to another close friend, the tireless philosopher Allan Bloom, in Ravelstein. Abe Ravelstein, with his runaway zest for life, buys expensive Lanvin suits and burns cigarette holes in them, gossips eagerly about his students, ardently watches the Chicago Bulls, and expects everyone, just like him, to be jolted into awareness by Plato and Rousseau.

“Somber, heavy, growling, lowbrow” Chicago, Bellow called the city that shaped him. He cut his teeth on that dour Midwestern master, Theodore Dreiser; his early novel The Victim features a Dreiserian character, Asa Leventhal. Asa is grubby, desperate, devoid of interesting or creative thoughts, and fearful of hitting bottom. He is afraid he’ll end up one of “the lost, the outcast, the overcome, the effaced, the ruined,” like Dreiser’s Hurstwood. The Victim, an earnest, accomplished depiction of a Jew, Asa, persecuted by his antisemitic Doppelgänger, reads like a fever dream.

After The Victim, though, Bellow’s lively brand of writing occupied the opposite end of the spectrum from Midwestern naturalism, the hard-as-iron aesthetic of Dreiser, Stephen Crane, and Frank Norris. These authors transmitted the grim messages of fate, but Bellow wanted to be “the representative of beauty, the interpreter of the human heart, the hero of ingenuity, playfulness, personal freedom, generosity and love.” Not until The Adventures of Augie March, his third novel, published in 1953, does Bellow break through into playfulness; his first two books are tight-lipped and constrained.

Bellow can communicate like few other fiction writers the sheer jostling thrill of living, breathing, arguing, seducing, and most of all—a Bellow specialty—sizing up the people and things around you. In an interview quoted by Sorin, Bellow commented,

I think I had a kind of infinite excitement going through me, of being a part of this, of having appeared on this earth. I always had a feeling ... that this is a most important thing, and delicious, ravishing, and nothing happened that was not of deepest meaning for you—a green plush sofa falling apart, or sawdust coming out of the sofa, or the carpet it fell on ... everything is yours, really.

Such excitement is carried by Henderson, the “absurd seeker of higher qualities,” in Bellow’s favorite among his own books, Henderson the Rain King, as well as by Augie March, who exults, “Look at me, going everywhere!”

The excitement was also about Jewishness, beginning with the book of Genesis, which Bellow studied in heder. “I was four years old and my head was in a spin,” he remarked. “I would come out of [the rabbi Shikka Stein’s] apartment and sit on the curb and think it all over in front of my house.” The biblical characters seemed like his own relatives, hot-headed, shrewd, and passionate bearers of mystery.

Bellow spoke a fine Yiddish until his last days. He grew up in the language, and never ceased cherishing its nuances. He remembered childhood days going to the movies in Chicago, when there was “a low rumbling in the theatre, that of dozens of child translators, himself included, whispering Yiddish to their mothers.” Yet, he admitted, he rarely picked up a Yiddish book as a grown-up. His future, he knew from early on, was in the American language that was spoken on-screen and in the streets.

[Bellow] stridently opposed Jewish schmaltz and the hawking of folkloric wares and shtetl nostalgia. Jewishness was about being an intellectual or a macher.

Bellow once remarked that he had taken something from Sholem Aleichem and the other great Yiddish tale-tellers—a conjunction of sadness and laughter, and a love of funny, bittersweet occasions. Yet Bellow’s uproarious ironies are written on a much larger scale. His ambitions were as huge as Eugene Henderson’s physique, while the Yiddish short story writers remained miniaturists. Moreover, for Bellow to write in Yiddish would have meant isolating himself from the mainstream, and falling under the limiting curse of the “Jewish writer.”

When Bellow began writing, in the ‘40s, Hemingway ruled the roost of American fiction. Too many young writers were compelled to emulate his taut existential ethos. Hemingway’s heroes felt at most a hard stoic joy, and that only rarely. They were chastened survivors of a battle with life. It was in the break with Hemingway that Bellow helped change the shape and texture of American prose.

Bellow’s Augie March was exuberant, rough and ready. A cosmic optimism radiated through this big ungainly book, not altogether unlike the hopped-up thrills that Kerouac was to deliver with On the Road four years later. In one of Augie’s scenes Bellow actually sounds like a Beat writer, when the hero and his Mexican friend Padilla sleep with two hard-up African American women. But the clipped, ambivalence-free diction of a Kerouac (who must have read Augie) doesn’t suit Bellow, and the scene falls flat.

Augie March is a grand, flawed book, complete with stray-dog Miltonic similes and Melville-like arias that career down the page. Augie is too unformed to be as passionately driven as Bellow claims he is, and some of Bellow’s proclamations about life force sound bald and unconvincing. But anyone who wades into Augie’s multitudinous pages is in for a treat. Here is one instance, Bellow’s portrait of Five Properties (a character based on Bellow’s brother Maury, and so nicknamed because, when pitching to girls, he boasts about his real estate):

That would be Five Properties shambling through the cottage, Anna’s immense brother, long armed and humped, his head grown off the thick band of muscle as original as a bole on his back, hair tender and greenish brown, eyes completely green, clear, estimating, primitive, and sardonic, an Eskimo smile of primitive simplicity opening on Eskimo teeth buried in high gums, kidding, gleeful, and unfrank; a big-footed contender for wealth.

See with what skill Bellow plants the odd word “original,” and how he provides that superb Whitmanian string of adjectives: “clear, estimating, primitive, and sardonic”! Five Properties’ Cyclops-like primitive nature and his cunning form a savory, unsettling mixture. This seemingly oafish but shrewd character embodies a kind of strategizing more full-blooded than could ever be deployed by the personages that Henry James creates, with their ballet-ish tip-toeing and peering into corners. Bellow draws on Jewish acuity and Chicagoan bluntness of manners to serve up an ace vignette, one of many in the book.

Augie, who ventures all over, winds up nowhere in particular. In the novel’s final pages he is stranded on the fields of Normandy, his car broken down. He has a new girl named Stella, and he dreams of settling down, though we somehow doubt he will. Augie neither makes his fortune nor is he broken on the wheel.

Moses Herzog, hero of Bellow’s breakthrough bestseller Herzog (1964), is to any objective eye, a failure. Crushed by his wife’s affair with his best friend (an episode Bellow transplanted from his own life), Herzog is rattled and worry-haunted. His house in the Berkshires is falling apart, with creaky rafters and a flooded basement. His life’s work, a book on Romanticism, is an inert heap of paper that will never be published. Everything seems to be rotting away, and Herzog might as well be squatting on the windowsill like Eliot’s gargoylish Jew in “Gerontion.” Yet the book ends on a note of fierce joy. In spite of it all, Herzog chooses life.

All through the novel Herzog relishes the vitality of his young daughter, the seductiveness of women, and even the energetic self-promoting shtick of his amorous rival, Valentine Gersbach, who is based on Bellow’s onetime friend Jack Ludwig. Herzog has interludes of unrelieved grimness, like a glimpse of a Chicago courtroom where Herzog witnesses the trial of a couple who have murdered their child. Here Bellow presages his gloomiest book, The Dean’s December, a dark masterpiece that pairs the forsaken ghettos of Chicago with the bleakness of communist Romania. Yet Herzog bounces back from his journey to the underworld. He does not deny the spiritual deprivation that makes life hell for some of us, but he knows that he wants to live.

Such a katabasis, as the Greeks called the trip to the underworld, features in other Bellow novels, like Mr. Sammler’s Planet, whose hero, during the Holocaust, crawled out from under a pile of corpses, having endured evils hardly imaginable. But the novel has its bright side too, speckled with portraits of ‘60s goofballs, like Sammler’s hippieish relatives Wallace and Angela. There is also Sammler’s nephew Elya, who likes to get on a plane to Israel and stride into the King David Hotel with no luggage—an irrepressible Jew who naturally stands up for others, and himself too.

Bellow frequently denounced the modernist viewpoint which sees the world as corrupt and valueless, with the alienated artist as hero standing against this modern spiritual desert. But he had another target as well, the notion that we must focus on worldly accomplishment, our noses ever to the grindstone.

Moses Herzog remarks, “The life of every citizen is becoming a business. This it seems to me, is one of the worst interpretations of the meaning of human life history has ever seen.” Americans often see life as a business, to be conducted with sober intent. One chief reason to read Bellow now is to disabuse oneself of the awful fixation on achievement that plagues what remains of our culture. Herzog is a failure, and so what? With his weird, unaccountable gladness he beats out the eager and calculating strivers, our intended role models.

Bellow treasured what he called “that mixture of imagination and stupidity with which people met the American Experience” (another line quoted by Sorin). We are more interesting for our flaws, flops, and spectacular faux pas, than for our shining successes.

The streets of Chicago were “raw, vulgar dynamic and dramatic,” Bellow said. He stayed true to those streets, their drama and dynamism, even though he often wrote about professors and intellectuals. But the hardnosed brutal calculus of Chicago existence never took over Bellow. Cutthroat devotion to the bottom line was simply not his way. He said,

There was not a chance in the world that Chicago, with the agreement of my eagerly Americanizing extended family, would make me in its own image. Before I was capable of thinking clearly, my resistance to its material weight took the form of obstinacy. I couldn’t say why I would not allow myself to become the product of an environment. But gainfulness, utility, prudence, business had no hold on me.

Long live the sheer imaginative power that marks pretty much every page that Saul Bellow wrote, along with the obstinacy, nuttiness, and pertinacity of his characters. The novelist Jeffrey Eugenides once said that he kept a copy of Herzog by his bedside, frequently opening it at random so he could glory in a Bellovian paragraph or two. Try it yourself, reader, and feel Bellow’s exhilaration going straight from the page to you.

David Mikics is the author, most recently, of Stanley Kubrick (Yale Jewish Lives). He lives in Brooklyn and Houston, where he is John and Rebecca Moores Professor of English at the University of Houston.