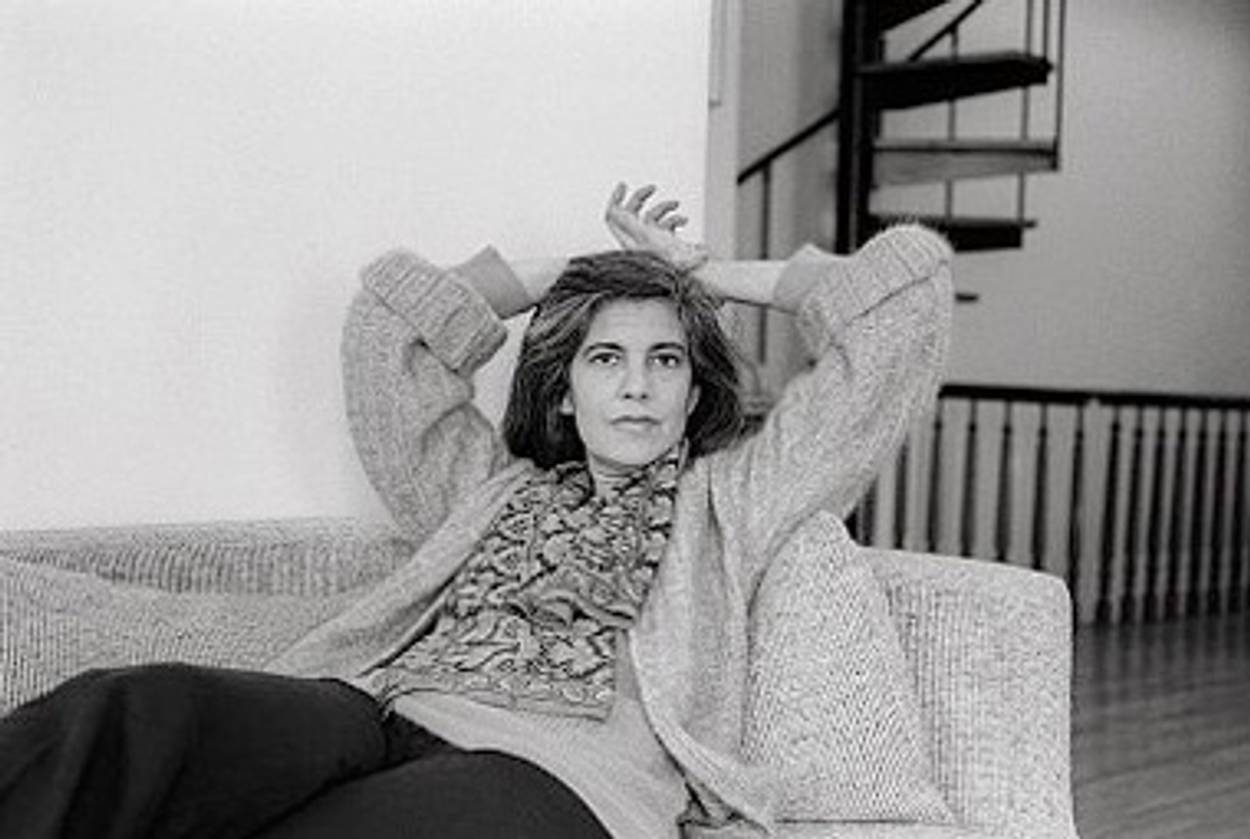

Role Model

Sigrid Nunez’s memoir of Susan Sontag in the 1970s shows the polarizing thinker in a rarely seen light—as mentor, hero, and muse

Two things you will not find in Sempre Susan, Sigrid Nunez’s slim, elegant memoir of Susan Sontag in the 1970s:

-a predictable rehashing of the notorious writer’s political gaffes and personal foibles—her apparent insensitivity to the American victims of 9/11 and her refusal to talk openly about her sexual identity (she was gay) being two of the best-known, and

-dish about Nunez’s two-year affair with Sontag’s son, David Rieff, the book’s ostensible raison d’etre.

Sempre Susan presents something else altogether, something I think the 20th century’s most famous and prolific female intellectual herself might have appreciated: a lament for not just a person but a lost era; an elegy for the woman whose “influence on how I write and think,” as Nunez puts it, “was profound.”

On the surface, the story the book tells is deceptively simple: In 1976, Nunez, then a 25-year-old aspiring writer, arrives at Sontag’s Manhattan apartment to work as her assistant. (Sontag by then had already written four well-received books: Against Interpretation, Styles of Radical Will, and two novels.)

Nunez begins dating Rieff, falls in love with him, and moves in. Two years later, she moves out. She and Sontag remain friends, albeit uneasily.

But beneath Nunez’s discreet girl-meets-boy story lies a revisionist, even radical, achievement: the most sympathetic portrait of Sontag to date. In considering Sontag through the story of her own coming of age as a writer—Nunez is now an accomplished novelist—she recasts a villain as a role model, hero, and muse.

Sontag, Nunez writes, took reading and writing seriously and, in so doing, gave Nunez “permission” to do the same. Sontag’s seriousness, one of the things that so many others mocked her for, served here as inspiration.

This is not to say that Sempre Susan makes the Sontag whose critics have variously described her as an elitist, a hypocrite, a traitor, and a Leninist, disappear. The sleight of hand here is that Nunez presents her subject as a woman who is those things and a touching, human figure. “One of her … first thoughts when she’d been told she had cancer,” Nunez recalls, “was ‘Did I not have enough sex?’ ”

Some readers are no doubt going to feel that Sempre Susan protests too much, that Nunez has an answer for every one of Sontag’s offenses. Sontag’s legendary lack of humor? She “laughed easily” and one of her stories is in The New Yorker humor anthologyFierce Pajamas; Sontag’s insistence that she was primarily an artist, not a critic? Her novel The Volcano Lover was a best-seller, and her In America won the National Book Award. Her well-known hatred of teaching and the academy? She was a perennial student. Besides, Nunez suggests, there’s a lot to hate.

I found many of Nunez’s explanations convincing, perhaps most of all her retort to those who accused Sontag of elitism. “She was not a class snob,” Nunez writes. “She was the kind of person who noticed that the uneducated young woman who cleaned her house for a time ‘had beautiful, naturally aristocratic manners.’ On the other hand, she never pretended that a person’s success did not depend . . . on being connected.”

Even more striking, though, is Nunez’s sympathetic treatment of how gender warped Sontag’s work and life. For Nunez, Sontag’s not being a man left her vulnerable to public ridicule—and perhaps even made her into the tantrum-thrower she was. “Was it because she was a woman that people felt they could address her like this,” Nunez asks after yet another audience member has viciously harangued her.

Nunez describes Sontag’s many efforts to keep up with the boys; she never carried a purse, for example, and ridiculed Nunez for putting Tampax in hers. Back then, it seems, playing a man in drag was the only thing a woman in the all-male world of the New York Jewish intellectuals could do.

Still, Nunez is too shrewd an observer to blame gender politics (or any other kind) entirely for her idol’s bad behavior and vicious takedowns. As she puts it, turning a literal fact from Sontag’s childhood bout with anemia into a metaphor, whenever the writer would indulge in a tantrum, “I’d flash on the image of her as a girl drinking those glasses of blood.”

If Nunez teases out Sontag’s gender bending, she seems less interested in the writer’s equally complex relationship to her Jewishness. Born and raised a secular Jew in California and Arizona, Sontag supposedly never went to synagogue until she was in her 20s. She lacked interest in Philip Roth’s novels, but she described herself as “a wandering Jew” and early on wrote sentences like, “Jews and homosexuals are the outstanding creative minorities in contemporary urban culture.” Her obsession with ideas approaches the Talmudic, and yet, writing about the Vietnamese, she expressed distaste for “Jews’ more wasteful and more brilliant style.” Two famous projects from 1974, Promised Lands, her film about the Yom Kippur War, and “Fascinating Fascism,” an essay on Leni Riefenstahl, reflect obliquely upon her identity but never confront it.

Sempre Susan limits itself to quoting Sontag as understanding Jews as “people who liked to touch and be touched, and who were voluble and confessional.” And funny. Her favorite joke, Nunez explains, was a Jewish one, which Sontag told with a Yiddish accent. “ ‘A mother. A neurotic child. Doctor, Doctor, vot should I do? Every time my little boy sees kreplach, he starts to scream.’ The punch line required that Susan, as the mother, clutch her head between her hands, and with an expression of stark fear, scream, “Aaahh! Kreplaaaaach!”

These snapshots make Sontag seem more like a caricature and less like the complex woman that Nunez has given us elsewhere.

This more-nuanced Sontag conjures a Hopper painting as she slips into her son’s bedroom to talk as Rieff and Nunez fall asleep on the futon—or something more sinister still in a scene where she’s trying to finish a book and her then 10-year-old son stands by, lighting her cigarette.

Nunez’s point is that her mentor, however flawed, taught her about life and art. On the final page, she recounts her indifference upon first seeing the luminous film Tokyo Story. Sontag’s response: Someday, you’ll get it.

Nunez reports: “Actually, it didn’t take years and I didn’t have to see the movie again.” Nunez quotes one character, Yoko, asking, “Isn’t life disappointing?” A second, Noriko, replies: “Yes, it is.”

Sontag, according to Nunez, unlike most everything else, rarely disappointed.

Rachel Shteir, a professor at the Theatre School of DePaul University, is the author of three books, including, most recently, The Steal: A Cultural History of Shoplifting. She is working on a biography of Betty Friedan for Yale Jewish Lives.

Rachel Shteir, a professor at the Theatre School of DePaul University, is the author of three books, including, most recently, The Steal: A Cultural History of Shoplifting. She is working on a biography of Betty Friedan for Yale Jewish Lives.