Romain Gary’s ‘The Kites’ Is the Best ‘Masterpiece Theater’ TV Series You’ll Ever Read

Bookworm: A new first translation of the French writer’s wartime epic

Can a book be epic without being great? This is a question I found myself asking again and again while reading Romain Gary’s The Kites, newly translated into English for the first time by Miranda Richmond Mouillot. The novel, which tells of a young man’s childhood and early adulthood throughout World War II, was published in France just months before the author’s suicide. Gary himself was an epic figure of French culture—twice the recipient of France’s highest literary honor, the Prix Goncourt, and a writer who earned national acclaim even for those of his works he put out under a pseudonym. This new edition of The Kites is blurbed by Charles de Gaulle and Jean-Paul Sartre. And so it is no surprise that I badly wanted for this book to be, not just epic, but great.

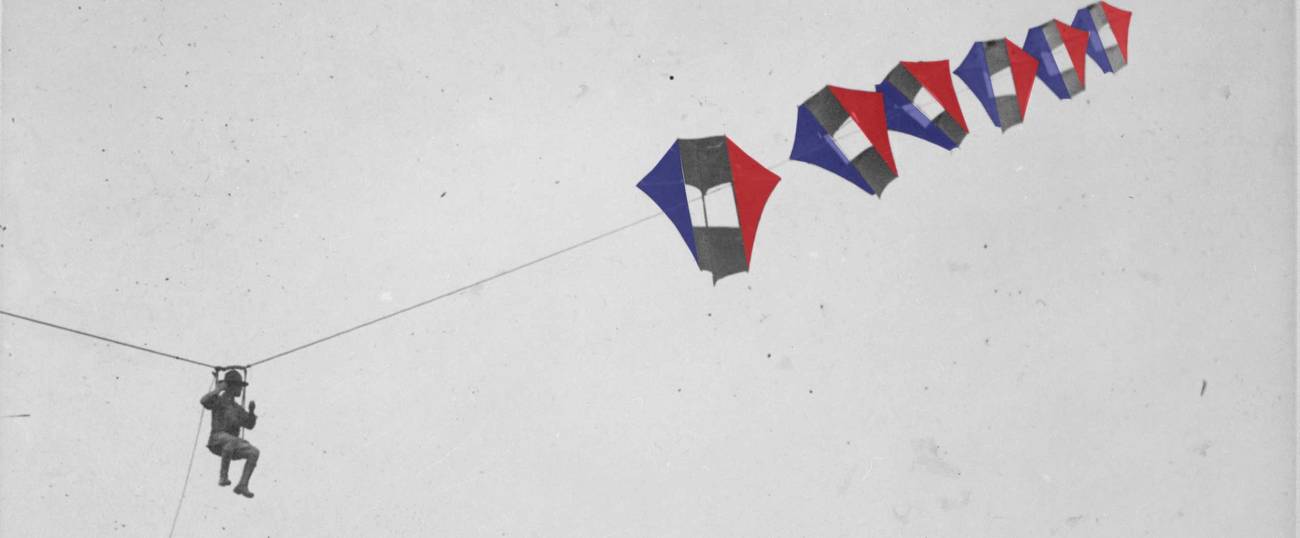

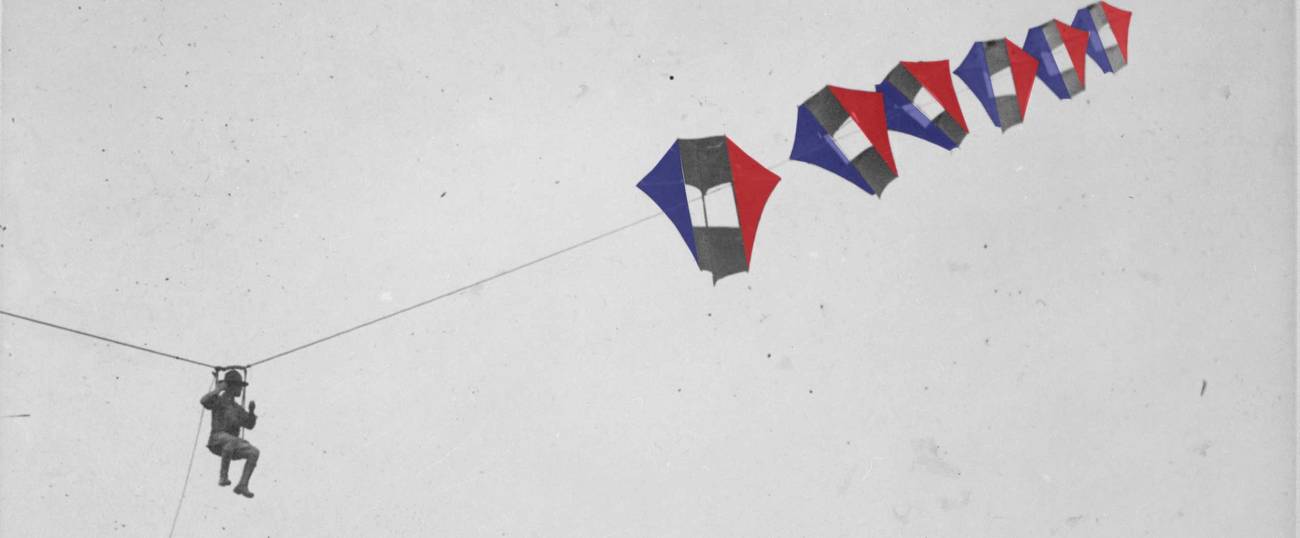

In the opening pages of The Kites its narrator, a young boy named Ludo, describes life with his uncle–a legendary local kite-maker—and the early days of Ludo’s love affair with Lila. The story itself is predictable, cheesy at times, as if the earlier parts were a cartoonish riff on the masterful childlike voice in Swann’s Way—not particularly compelling but enjoyable enough to read. And yet a part of me that has spent entire days watching Masterpiece Theater also knows that this book, even at just 300 pages, would be able to sustain three whole seasons of something I’d recommend to everyone I know. If the 2010s needs its own Brideshead Revisited series, it should be The Kites, starring Jeremy Irons as the batty but wise kite-maker in northern France.

As Ludo grows up, he becomes an apprentice to Lila’s father—a wealthy Polish aristocrat who at the onset of the war leaves France. Like a Dickens novel, part of the story of The Kites is one of class and station and the deep incompatibility that these realities can inflict even on great loves. Ludo loses his childhood innocence as he becomes increasingly oppressed by an understanding of his role in the world. The novel begins examining a world on the brink of disaster: Troops mobilize, borders become harder to cross, France stares into the abyss of a second massive war. Meanwhile, Ludo tells of an aristocracy in deep denial of its impending demise and eventually goes to join the fight.

The Kites is one of those novels that can skip whole years and seamlessly glide over chunks of time. It is epic in the way that only stories about WWII can be, where the magnitude of history tussles with the monumentality of other histories, family histories, lives interrupted, lives hoping to be resumed, things that ultimately that have nothing to do with the war itself, which is simply a bump in the road. Like any great wartime epic, the lives of its characters are able to deflect the supremacy that war typically has over narrative.

But Gary’s wartime epic is not Dr. Zhivago. It is more similar to a Zola novel—several hundred exciting pages in which the author never even bothers to dig into a character’s internal life. It is largely superficial. Gary deals almost exclusively in facts. Very rarely do we get a deep sense of what Ludo is thinking or, as has become the hallmark of great French writers like Stendhal, a deep sense of what others are thinking. It’s not an incisive book. There is no trademark French literary psychology.

Some of the best moments in The Kites come when Gary lets his guard down and digs a little deeper. In one scene Lila laments that she probably won’t be able to do anything meaningful with her life, and immediately her brother and cousin assure her otherwise. Ludo, meanwhile, an orphan under the care of his batty kite-maker uncle, hopes that she’s right, knowing that Lila’s inability to do anything with herself is the only thing that gives him a shot. In another scene Ludo realizes Lila’s brother, one of the better characters in the book, is not, in fact, the anarcho-ironist he appears to be, but rather a deep humanist who is simply lonely. These moments are rare, and as a result, all the more frustrating because it’s clear that Gary can inhabit his characters fully but simply chooses not to. Similarly, Gary’s prose can be masterful but is only ever on full display in descriptions of nature or in the last two or three sentence of a chapter.

The Kites is compelling not because it is innovative and breathtaking, or because it can explore the human depths of its characters, but rather because it so faithfully executes the epic form. It moves across a decade without feeling clunky or disjointed, coaxes young characters toward adulthood, and has a keen historical eye. All of these require great artifice but do not always give us a great work of art. It would, however, make fantastic television.

Alexander Aciman is a writer living in New York. His work has appeared in, among other publications, The New York Times, Vox, The Wall Street Journal, and The New Republic.