Sales Figures

A skillful new Broadway revival of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman cannot overcome the flaws of this dated and stilted play

Was I a “glutton for punishment”? That’s what Mary McCarthy called theatergoers who subjected themselves to plays she called “sadistic fantasies in realistic disguise.”

Mary McCarthy hated Death of a Salesman. I did, too.

So, I thought about her as I watched Mike Nichols’ revival of the 1949 iconic drama, currently at Broadway’s Ethel Barrymore Theatre, that critics have long called Arthur Miller’s masterpiece, his finest play, indeed, an American tragedy.

There was much to praise in Nichols’ rendition of Death. But despite his brilliant direction of a gifted cast, superb sets, lighting, and music, my aversion to this play could not be denied: Salesman is awful.

To begin with, Death of a Salesman is melodrama, not tragedy, as the old chestnut about the play asserts. Two men are discussing the play after a performance. “Such a pity!” one says to the other. “He had the wrong territory.”

The dialogue of this ostensibly timeless American saga is dated, clunky, and artificial. Consider the play’s emotional climax—long-suffering wife Linda’s impassioned defense of her husband, who has descended into suicidal dementia even before being fired. “Attention must be paid,” she says. And in case you missed it the first time, Linda repeats her shrill command: “Attention, attention must finally be paid to such a person.”

Who talks like that? No one. Who ever did?

The words ring false because they are false. And this artificiality underlies the play’s essential flaw—its absence of real characters. Willy Loman is, as Linda needs to remind the audience, a person. Or make that a Person. For as McCarthy wrote in Sights and Spectacles, 1937-1956, Willy is a “capitalized Human Being without being anyone.”

Although Willy seems to be Jewish, judging by his speech cadences, he could not be Jewish because as McCarthy observed, he had to be “America.” “Wholly conceptualized,” she wrote, the play is filled with stereotypes, with “cut-out figures.” Willy Loman is not a man, but a “type.”

Miller’s own stage directions make that clear. Willy’s mistress is called the Woman. Willy is called the Salesman.

Miller’s ambitions were obviously huge. By erasing Loman’s specificity as a human being—as a Jewish salesman—Miller undoubtedly thought he was creating something grander and more enduring. But as the Greeks surely should have taught us, tragedy is universal only when those experiencing it are seen as flawed individuals, not merely stand-ins for the “common man.” Miller’s desire to erase Loman’s specificity to give him universal resonance created an abstraction, or as the (Jewish) joke suggests, a salesman with rotten territory.

Miller, of course, was not the only writer of his era who sought such universal resonance in assimilation. The promotion of “humanist” politics was characteristic of many liberal and leftist Jewish writers of his generation. But just as McCarthy was astonished by the play’s popularity at the time, its endurance—its performance at every high school, college, and regional theater company, not to mention at least four revivals on Broadway—attests to the flatness of the dramatic earth around it, the relative paucity of great tragedy from American playwrights, then and now.

Most critics, of course, did not share McCarthy’s view. As the hosannas piled up, Miller became a celebrity, and his sense of his worth and work grew as well. In an interview with Christopher Bigsby in 1990, he compared Death—favorably—to King Lear. The problem with Lear, he says, is that the gloom is “unalleviated.” Setting aside “the beauty of the poetry,” Miller observes, “Learis unredeemed; he really goes down in a sack, in a coal chute.”

McCarthy, too, compared Miller’s play to Lear. Both plays, after all, deal with “an old man, failing powers, thankless children and a grandiose dream of being”—as she put it—“well-liked.” But Lear was not just any old king. “He is Lear.”

My aversion to Miller’s play is not widely shared—by critics or by last week’s audience at the Barrymore. Theatergoers clearly adored Nichols’ faithful revival, weeping at the play’s cathartic moments and awarding the talented cast a standing ovation. But many even mediocre offerings routinely receive such adoration on Broadway these days.

To be sure, there is much to admire in Nichols’ superb production, above all his direction with its clear narrative line and crisp pacing. His use of Jo Mielziner’s original skeletal, intentionally claustrophobic set and composer Alex North’s spare, haunting score—which opens the play with the notes of a lone, mournful flute—evoke an earlier chapter of American life. Nichols knows this is a period piece.

Nichols, who at 82 shows no signs of slowing down, sensed that the time was right for such a revival. “People are counting pennies again,” he told Christopher Isherwood of the New York Times. “We owe $28 dollars on this, and you gave me $50 at Christmas. Fixing the water heater will cost $97.50,” he quotes the play’s true hero, Linda Loman, as she goes over household math with husband and now non-provider Willy. Just once, he replies, he wants to have paid in full for something before it breaks. For far too many middle-class Americans, the reference to installment payments is no longer a throwback. Economic times are tough.

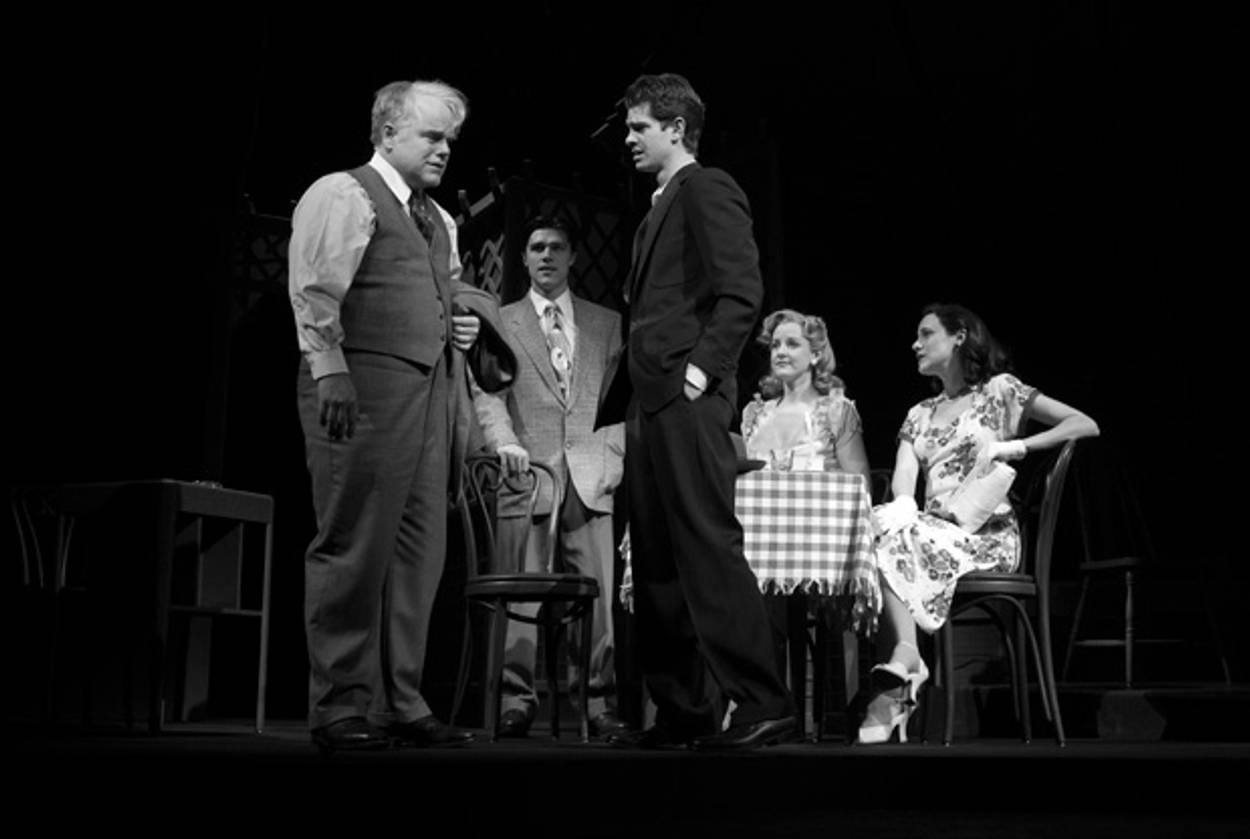

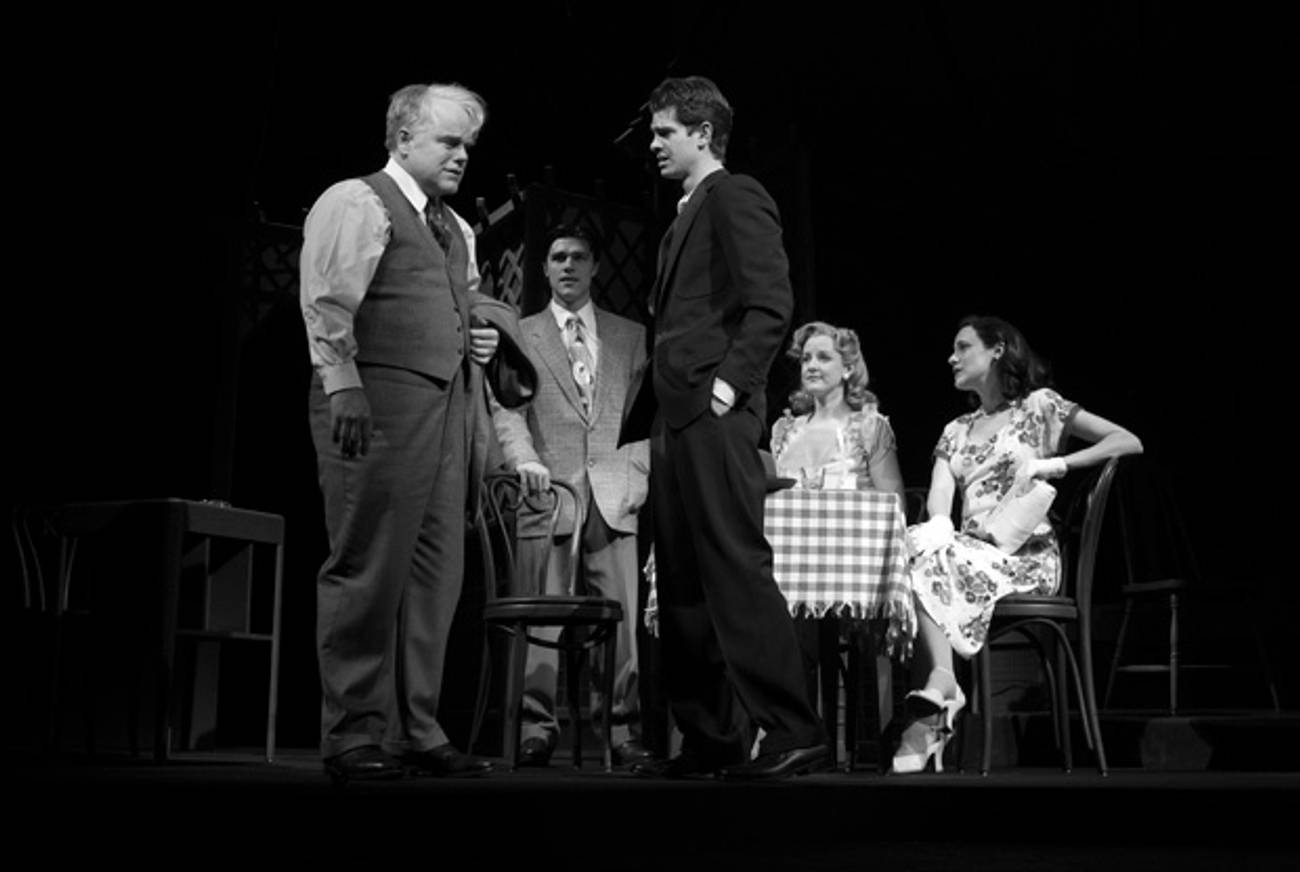

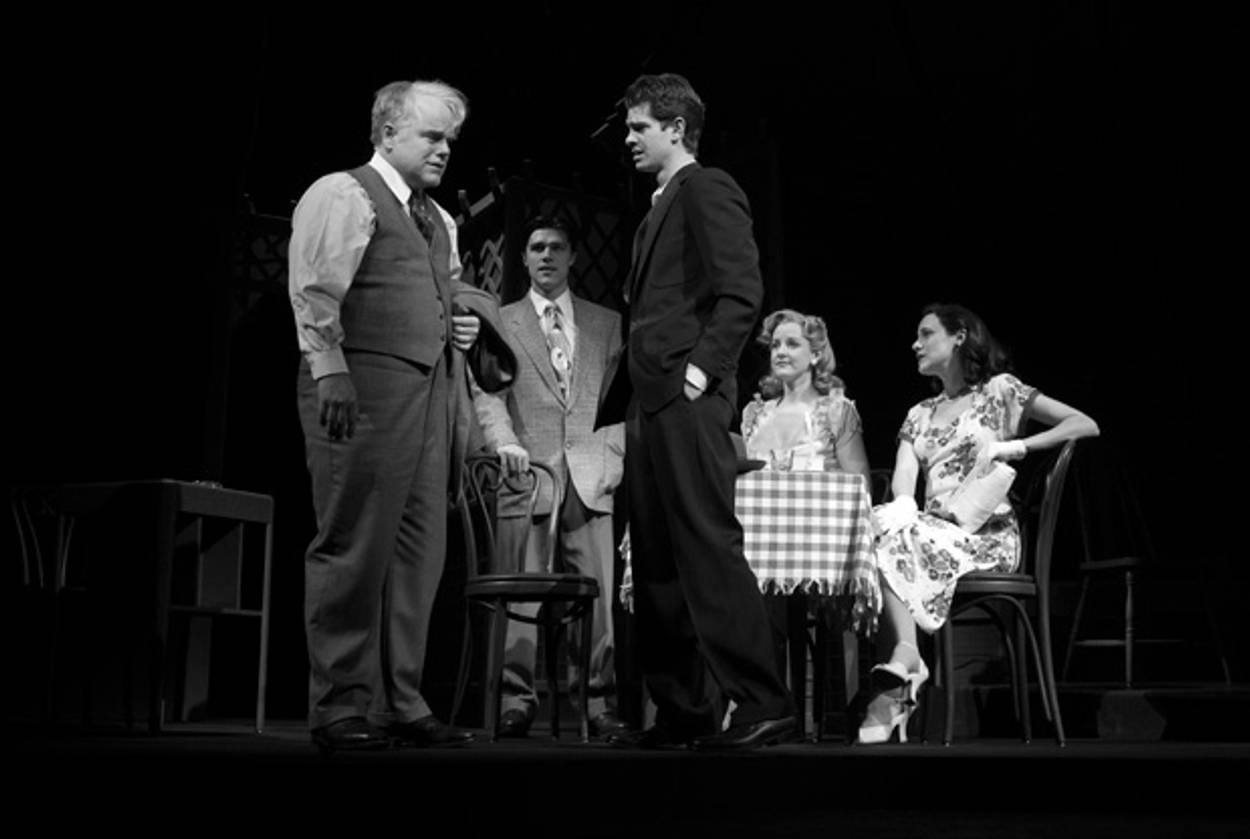

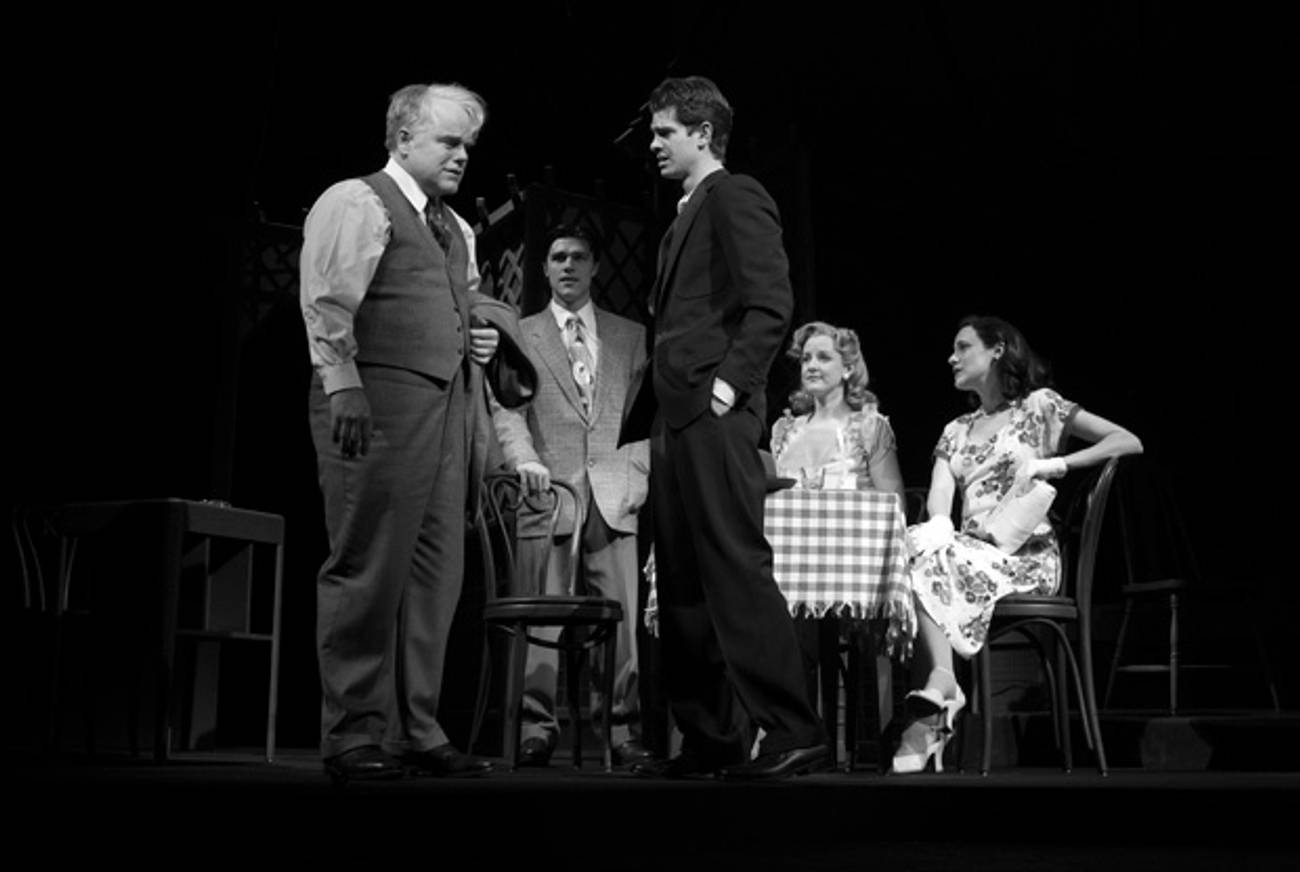

One also suspects that Nichols relished an opportunity to direct Philip Seymour Hoffman, who demonstrates yet again why he is one of the nation’s greatest young actors. While 44 may no longer be young, Hoffman was young to play a 60-year-old man sinking into suicidal despair. But so too was Lee J. Cobb, the original Willy Loman, who was only 37 when he defined the part on Broadway. Only rarely did Hoffman’s age come to mind. He was usually credible as the sagging, defeated, self-deluded Willy. Since the play gives its lead character almost no transitional material—Miller took inexplicable pride in that—Hoffman invented his own. A single gesture—the raising of his right-hand fingers to his forehead—foreshadows yet another moment when life is about to overwhelm him. Hoffman’s navigation of Willy’s rapid shifts from memory to the present makes his performance impressive.

Willy is not the only cardboard character cast against type. British-American film actor Andrew Garfield (whose Eduardo Saverin, Facebook co-founder, in The Social Network was subtle and superb) gives an intense performance as Willy’s 34-year-old, all-American son Biff. A football star in high school, Biff has wandered from job to job, ranch to ranch, never finding success as father Willy defines it, or personal satisfaction either. Garfield delivers an emotional punch, especially during the play’s powerful confrontation with Willy, in which he rejects his father’s dreams and values.

Far better cast and dramatically more credible is Finn Wittrock as Willy’s shallow younger son, Happy, who unsuccessfully craves his father’s love but has little of his own to give. Wittrock, another Broadway newcomer, is all-too-credible as the caddishly creepy son who, unlike Biff, buys into Willy’s standards and delusions and, one suspects, not merely to rise in his father’s affections.

Smaller roles, too, are also well-played. Bill Camp, as Charley, is the Lomans’ shrewd, seemingly passive but supportive neighbor, Willy’s only would-be friend. Fran Kranz is memorable as Bernard, the Lomans’ sons’ geeky pal whose success is another reproach to Willy; John Glover is flawless as the dead adventurer, wealthy brother Ben, whose spectral apparition constantly reminds Willy both of his own failure and potential economic salvation; Molly Price, as Willy’s Boston mistress, is a splendid mix of lower-class sexy and cunning. She has a ferocious giggle.

Attention must also be paid to Linda Emond for a performance that transforms Willy’s wife from a subservient doormat—an “enabler” as one dim feminist reviewer called the character—into an almost real person. Emond’s Linda knows her husband’s imperfections and loves him anyway. She is Willy’s cheerleader, defender, accountant, and the human glue that holds this dysfunctional family together. When she announces at Willy’s tomb that she cannot cry, I wanted to cheer. Why should any real or fictional woman who has endured such a life with Loman—who her creator, Arthur Miller said, “wiped the floor with her”—do otherwise?

Judith Miller, Tablet Magazine’s theater critic, is the author of the memoir The Story: A Reporter’s Journey.

Judith Miller, Tablet Magazine’s theater critic, is a former New York Times Cairo bureau chief and investigative reporter. She is also the author of the memoir The Story: A Reporter’s Journey.