A Hoofer in the Slaughterhouse

A Neue Galerie retrospective celebrates the great Jewish image-maker ‘Madame d’Ora,’ who helped avant-garde stars like cabaret dancer Anita Berber rise—and fall

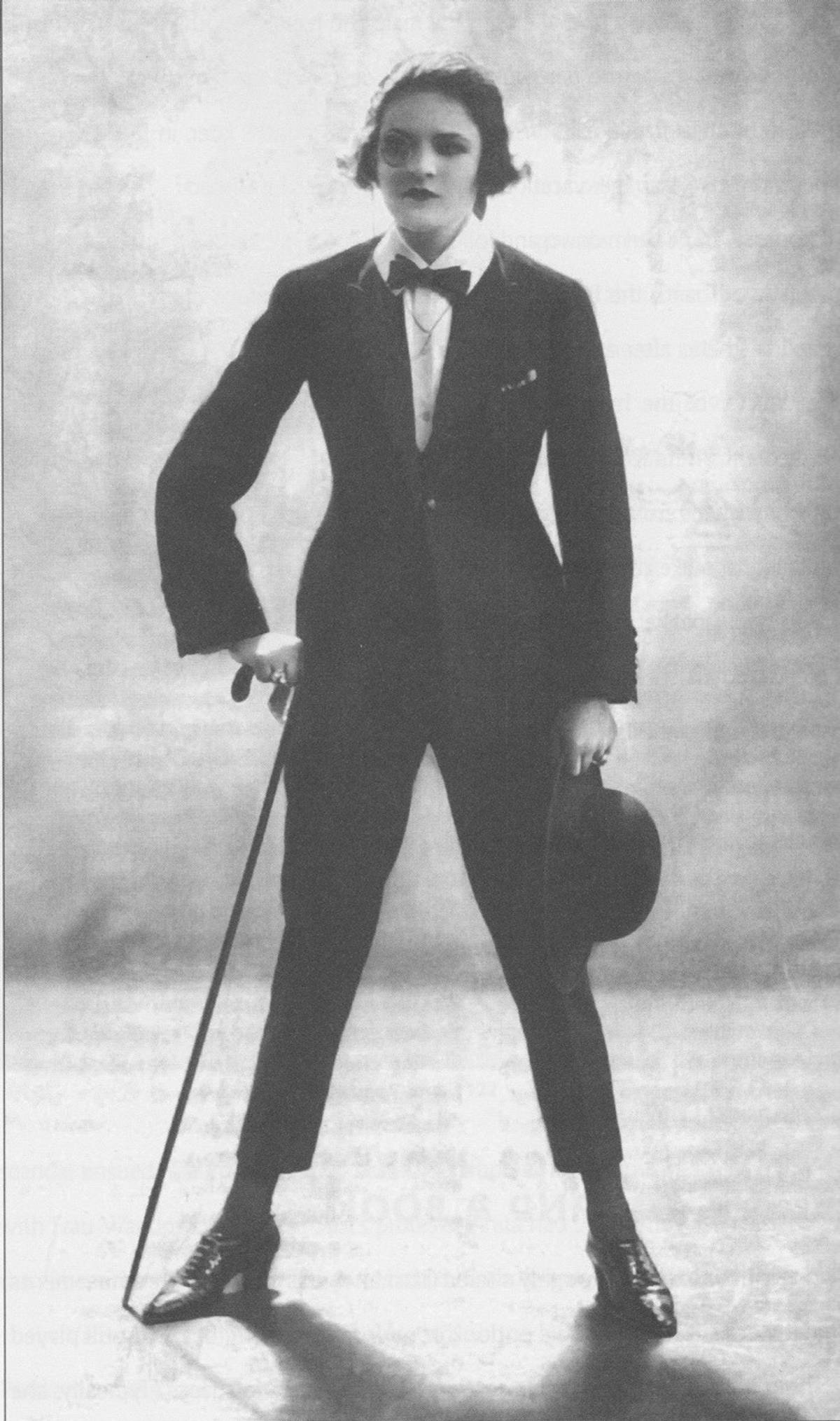

I kind of went nuts. In Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse the Gambler (1922), she appears in a fancy nightclub full of occupied two-tops, standing all by herself on the dance floor in a debonair tux, jiggling her shoulders, elbows tight to her ribs, head cocked, a wink. Even though it’s a silent film, I can hear her clattering soles, and overhear a comment, “Is that a man or a woman?”

It was the first time I saw Anita Berber, one of the biggest cabaret stars of the 1920s and ’30s—a magical being! Her life story is all over the web. And over-the-top. Her most devoted bloggers all seem to want the world to know who this obscure transgressive talent was, and what she stood for.

Berber was from Dresden. After her bohemian parents divorced and left her in the care of her grandmother, she was enrolled in a progressive school and trained in eurythmics—the art of musicalizing the everyday task of living. At 14, Berber moved to Berlin, joined a radical touring dance company and began to collaborate with another pioneer of expressionistic performance art, Valeska Gert.

Berber’s act became increasingly sexually explicit as she began to gain a following and capture the interest of movie moguls and critics. Still in her early 20s, and being hailed as a “wonder in the art of dance,” she cultivated a unique style that took on a decidedly erotic tone and transgressed the conventions of taste and morality. In a nutshell, she was punk.

This was all a revelation to me. The “Eurythmics” have always been the catchy name of a pop duo that appeared on MTV in the ’80s. And Cabaret was a Broadway musical featuring a jazz dancer straddling a backward-facing chair. Any larger notion of the German-speaking nation was a stain that left me in perpetual denial. I guess I had PTHSD, Post-Televised-Holocaust Stress-Disorder. I’m now inclined to ask, where was Berber when I needed her? Where was her irreverence and audacity when I first began not taking “no” for an answer? Why can’t I remember a single cabaret in my suburb?

Berber-culture had me in its clutches. I was reflecting on what it should be like to be a young artist, laying it all on the line, trying to wake people up from their comas … from their inhuman, brain-dead indifference, using every available tool to bust out. Soon I discovered Berber modeling in a 1919 folio of erotic prints by Charlotte Berend-Corinth, which are infamous for their naughty depictions of Berber in eight burlesque personas. To quote Berber’s biographer, the late scholar Mel Gordon, we are introduced to “the inviting whore, sensationally naked except for an open black overcoat, rolled up stockings and high heeled pumps”—and there are seven more where that whore came from.

I prefer to think of Berber less as a vintage porn star and more as a highly skilled avant-garde dancer, actor, poet, and muse, who, by pushing all of these media to (and past) their fullest potential, skyrocketed at a young age to becoming a sex symbol of a roaring epoch, combining beauty and danger in works of expressionistic, erotic, eurythmic, myth-construction. The writer Klaus Mann (son of Thomas Mann), described his first impression thus: “Her face was a somber and vicious mask. It seemed obvious that the strongly curved mouth was not her own but was a blood-red concoction out of a little pot of rouge. The chalky cheeks had a violet shimmer. The eyes required at least an hour of work every day ...”

Most images of Berber were taken by the period’s high-profile photography studios, like Atelier Binder, and Atelier Eberth. What was their use back in the day, I wondered? PR? Indeed—optimally published in magazines or used as promotional postcards (prime time for many an autograph-forger). Clearly Berber had her share of adoring fans, who would have been hungry to bring a little piece of her home to hide under the pillow.

The most fascinating still images of Berber were products of Atelier d’Ora—unquestionably the most artistic and pervasive studio of the time. Madame d’Ora was the international photographer of the most sensational people of the day, be it in Vienna, Berlin, or Paris. She was the Doc Holliday gun-for-hire who helped stars go pop.

Numerous d’Ora photographs show Berber with her collaborator Sebastian Droste, who eventually became the second of her three husbands. The pictures were taken for a book they were publishing at the time called Dance of Depravity, Horror and Ecstasy, also containing the spoken-word poems they would recite during their live dance show—shows with titles like “Byzantine Whip Dance,” “Cocaine,” “Martyr,” and “Suicide.”

“Cocaine” shows Berber as a femme fatale in a lace-up black bustier peering out from behind a black curtain. As Mann once wrote: “Anita Berber—her face frozen into a garish mask under the frightening locks of the scarlet coiffure—dances the coitus.” Another striking photo from the series shows a very skinny Droste with annoyingly narcissistic sideburns waxed into two pointy spirals melded with Berber into a single form—a pose of Wagnerian liebestod. The Czech choreographer Joe Jenčík once described what he witnessed on stage. “Tiny spasms of the body take hold of the porcelain-colored limbs, and the unfortunate drugged woman regains consciousness … When she sits up, the muscles sway like the motions of a drawn-out pendulum …”

In one of the most iconic photographs, Berber is stark naked on her knees with her back arched, reaching up and clinging to Droste’s naked rib cage and lean torso, as he thrusts upward with gothic angst, like a vampire under a full moon. Droste once stated that their dances derived from “tormenting, breast-tearing, agitating experience.” One of the equally excessive fetishistic poems in the book reads: “Twenty-thousand women in corsets bite each other in ecstatic lust.” According to her biographer, Gordon, after bringing Berber to the frenzied climax of her career, Droste left her high and dry—he pawned her furs and jewels for a ticket on a trans-Atlantic ocean liner to New York, where he managed to pass as a baron, con his way onto the stage at Carnegie Hall, and began a new life as a sex guru in an upstate love colony. It’s all too good to be true. Or too true to be good.

After a little more research into Madame d’Ora, I was delighted to find a major retrospective in New York City at the Neue Galerie, set to run through the summer but currently closed due to COVID-19. Berber, I would now learn, was merely one of many planets orbiting d’Ora in her complex universe, one of the many colorful characters to appear in d’Ora’s exquisite black-and-white photographs. During her reign in portrait and fashion photography—as cameras were becoming affordable, and photography was swiftly replacing graphic illustration in fashion magazines—Madame d’Ora contributed regularly to Die Dame, the journal Ullstein founded in 1912, and many others. Stars shot by d’Ora would regularly “get the cover,” and arguably go out onto the most visible stage (page) in the world.

As pop culture boomed, d’Ora’s bread and butter increasingly came from fashion shoots and/or photo essays produced in collaboration with important designers to publicize the latest reform dresses or impractical hats. It was d’Ora who, in certain ways, invented this new genre—coupling celebrities with fashion houses, to create maximally desirable commercial images, a prime example being her famous 1927 shoot of Josephine Baker in a Jean Patou dress.

And yet, it was not always d’Ora doing the matchmaking. The industry had its own mysterious machinations, and it’s hard to pinpoint in retrospect who was responsible for any particular star’s rise to fame. Had d’Ora used her influence and her unique sense, to elevate that next sexy thing? Or was creative power in the hands of the magazine editors, who then hired d’Ora, or any one of her competitors, to “do their thing.”

D’Ora also shot people who weren’t exactly going anywhere. There were many lazy self-portraits with cats, and close friends with dogs—she loved to take in pets. D’Ora’s genius was getting her clients to trust her—to relax under her lights and feel at home in front of the big scary camera. Her alchemy was her charm, and ability to meld the intangible sexiness of the moment into a dramatic yet formal picture. Perhaps she possessed the Warhol gift for flattery—I wonder if she could have been a little like Andy in his factory with his ubiquitous Polaroid always at the ready, telling Candy Darling or some other diva how beautiful she looked. She used props, lighting, and composition to lift people into an imaginative realm, to make them appear on film more extraordinary than they would look back home in their bathroom mirrors. In other words, she was able to play the high-society game that got painters of the gilded age like John Singer Sargent on the museum guest list.

But people of status were ready for her. Progress had been made, not only in the technology of photo equipment and printing but also in the way people perceived themselves—and presented themselves to the public, and to posterity. Clients who in the past would have settled for being stuck in stiff poses by bossy photographers were now inclined to pay d’Ora the big bucks to show them hanging looser. Women especially were growing increasingly confident, and therefore comfortable being seen as flawed beauties in their natural bodies. Even uptight aristocrats trained in etiquette began to loosen their corsets and allow Madame d’Ora to tease out and maximize their assets.This classwide faith in the d’Ora touch is especially evident in the work that emerged after she moved to Paris in 1925, when she shifted her focus to couture and befriended the Spanish designer Cristóbal Balenciaga, and France’s most popular milliner (with her shop on Rue Saint-Honoré) Madame Agnes, as well Cecil Beaton, Maurice Chevalier, the mega-lesbian author Colette, and other lights of the Parisian glamour industries.

But, to my eye, d’Ora’s most poignant and nuanced photographs are her earlier portraits of gutsy avant-garde performers caught in the act of pushing the edge of their creativity, like Berber and Droste—or Anna Pavlova, prima ballerina of the Imperial Russian Ballet and Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, who is best remembered today for The Dying Swan. Many such images are not so much vogue as they are vibrant and emotionally gripping. They bring to mind Richard Avedon, in their empathy and charisma.

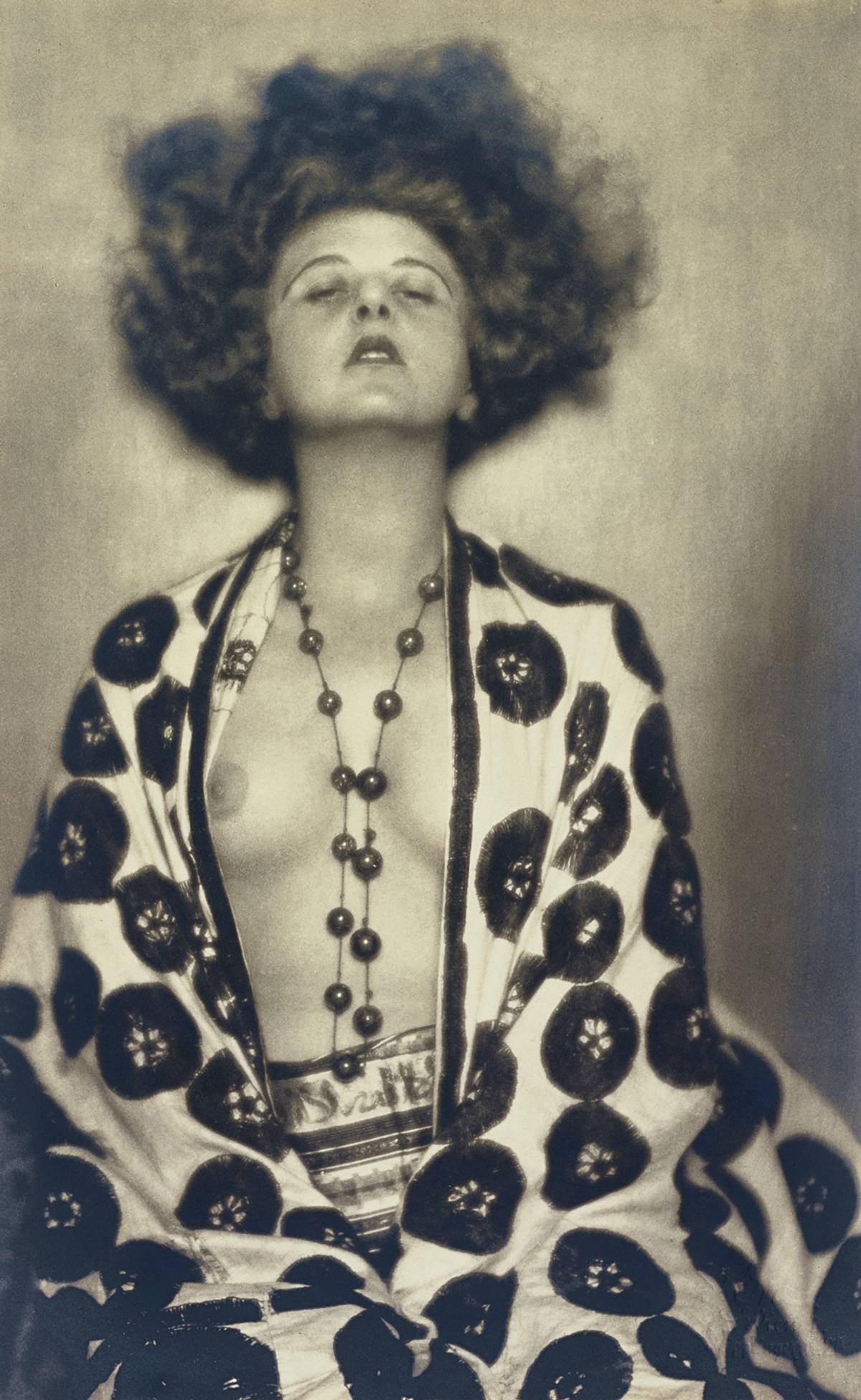

Consider d’Ora’s very famous portrait of the operetta singer Elsie Altmann-Loos. A big-beaded necklace dangles down between her open floral patterned silk robe, along one partially exposed breast. Her bushy hair is swept back into a batch of blurry darkness (a darkroom technique); her head is tilted back violently so that we see right up her nostrils. I’m tempted to compare the image to Man Ray’s 1925 arresting portrait of the mop-headed mannequin-like Helen Tamiris, which teeters on the verge of surrealism.

In the portrait of Altmann-Loos, one can feel the excitement of the moment, as if the singer is standing backstage about to go on. Her exhilaration (a studio recreation) has been preserved in a jar and is still fragrant, and perhaps still fashionable. D’Ora allows her to bask in her timeless imperfections, to be ravaged and not judged. In 1928, Altmann-Loos once confessed how badly her verbally abusive husband the architect (and convicted sex offender) Adolf Loos made her suffer: “I have always been a woman-child and this is what Loos loved in me,” she said. “But all of a sudden, he finds that I don’t have sex appeal, and moreover, that my legs are too short. If I had longer legs, he said, it would change my life. So Loos decided to take me to a surgeon who would break my two legs and elongate them.”

D’Ora’s picture tells a remarkably different story, free of such misogynistic insanity. Which brings me back to the gender-bending Berber, whose artistic achievement is forever linked to her fabled anti-heterosexuality—her terrorizing of men (and patriarchy) through the dominance of her sexuality. And how, more broadly speaking, her biography eclipsed everything, rising from her emboldened theatrics into a fascinating and infinitely liberating work of folklore.

Indeed, Berber’s story only got better as her decadent lifestyle began to spiral out of control, and gossip about lesbian encounters, public nudity, and drunkenness as well as very heavy drug use appeared in Berlin’s daily tabloids. Berber decided to occupy an extravagant suite at the Hotel Adlon, and from here she basically went on a hedonistic binge—spending wildly on furs, shoes and jewelry, and indulging in a nightly fix of heroin, cocaine, and cognac (all at once). Thus began her escapades bar-hopping and bouncing from hotel lobby to hotel lobby in a sable coat, with (apparently) a pet monkey clinging to her shoulder, and that ominous long dangling antique brooch she’d always have around her neck packed full of cocaine. Berber would pose naked in private or pull open her coat and flash her athletic “hard body,” as it’s properly called these days. On the other hand, Berber is often seen (especially in photographs) as a dirty little tramp. In some pictures, her palette of theater makeup translates as the charcoal eye-socketed poor little rich girl who has taken daddy’s money and gone Goth.

Befriending another highly innovative flapper (and d’Ora client) named Marlene Dietrich, Berber taught her younger protégé how to brag about her talent for fellatio. And make ludicrous claims, like one of her favorites: to have worn out all three of her husbands due to her insatiability in the sack, before then moving on to women. After a 1926 performance at the Metropol Theatre the following police report was filed: “In dances 1, 3, and 4, Berber appeared in entirely see-through clothes, with fully exposed breasts, unclothed backside, the genitals only inadequately covered by narrow ribbon.”

But Berber’s rebel mystique had more to do with excessive drug use than sex. She was a reckless partier, with a taste for everything. Her favorite form of inebriation was this exotic homemade pharmaceutical: chloroform and ether stirred in a bowl with a white rose, allowing each petal to be picked off and nibbled. This was clearly a creative addict at work.

Her speedball recipes caused her to behave erratically, not to mention unprofessionally, on stage and off. She was known to arrive late and too wasted to go on stage. She’d take out her injection equipment and shoot cocaine into her thigh right at the table. According to one gossip columnist, she once noticed that someone in the audience wasn’t paying attention to her and she smashed an empty bottle of champagne over his head—then stepped up onto his table and urinated. Who knows if there’s any truth to even half of it. Did she actually spend a night (or was it five weeks?) in prison after insulting the king of Yugoslavia? Was she really the sex slave to a woman and that woman’s 15-year-old daughter? I doubt we will ever know.

The show at the converted townhouse of the Neue Galerie is a far less degenerate affair. On the contrary it is almost too respectable—a little too clean. Knowing of characters like Berber, one begins to desire a little more dirt. The show, which is called simply Madame d’Ora, has been curated by the Viennese art historian Monika Faber, who would have also had a certain PR nightmare to contend with, stemming from Mr. Lauder’s seemingly misguided mega-donations to Republican super PACs, and the museum’s pretentious Café Sabarsky, which may be perfect for ladies who lunch, but nobody else—unless it is your desire to settle down with your diary and indulge in some Josef Hoffmann lighting, Adolf Loos seating, and vintage Otto Wagner fabric while waiting for your faux Viennese waiter to deliver your coffee on a silver platter.

But Madame d’Ora delivers its own compelling and often gritty story as WWII led her into the darkest of darkrooms. A new appraisal of d’Ora’s late work, in fact, would position her closer to the bleak existential moment in photography that we associate with Lee Miller.

So, who was she? Madame d’Ora was born Dora Kallmus in 1881, into a typical classy and cultured Viennese Jewish family, surrounded by a creative and intellectual atmosphere and a diverse circle of sophisticated, high-achieving friends. She was fortunate to attend concerts and exhibitions and to be brought on vacations with her parents and governesses. She had a sister, Anna, three years her senior. Her mother, Malvine (maiden name Sonnenberg) died when she was 11. Her father, Philipp, was a government lawyer, which connected the family to high-ranking public officials, prominent people in banking and business, diplomats, and members of the aristocracy.

Kallmus had ambition to spare and plans to become fashionable. To this end she chose a path in photography, which was hardly the expected lifestyle for someone of her social set. By 1905, she’d been accepted into the Association of Austrian Photographers. She was the first woman to study theory at the Graphische Bundes-Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt, before women were permitted to study photography. In 1907, Kallmus went to Berlin for a five-month apprenticeship with the influential portraitist Nicola Perscheid, whose itinerant approach (he was back and forth between Berlin and Austria) would have impressed Kallmus, who had similar entrepreneurial vision and natural networking ability.

Perscheid was developing a new kind of soft-focus camera lens, with a wide depth-of-field for large format portrait photography, but it was undoubtedly his traditional sense of pose, facial lighting, and composition that made an indelible impact on Kallmus. His portrait of Klimt’s model and lover Fräulein Sakur is pure old school art nouveau. In a 2005 New York Times review, the critic Grace Glueck described Perscheid as “Berlin’s court and celebrity photographer par excellence,” and commented on Sakur’s enormous hat, her enveloping gown and soulful gaze, and the book she holds in her dangling hand. Glueck hypothesizes that her finger is marking “a swoon-y romantic passage.” Being a product of her time, Sakur could only have dreamed about the sort of life that demonic creatures of the next generation like Berber would go on to feverishly haunt and flaunt.

After her schooling, Kallmus returned to Vienna where her family used its significant influence and wealth (it is said that she received a “horrendous” sum of money from her daddy) to help her furnish her studio, pay employees, and establish her brand—Atelier d’Ora.

Enter Arthur Benda. D’Ora talked the young photographer she had gotten to know during her time with Perscheid into abandoning their great master and coming to Vienna to become her technical assistant, cameraman, and eventually, her business partner. Both of their names soon stamped each image—signifying that maestro Benda was behind the camera (and in the darkroom), while Madame was out in front schmoozing her ass off. In 1925, d’Ora and Benda opened a second studio in Paris. But their dream team hit a bump, and sadly two years later their relationship came to an abrupt end.

Kallmus’ success continued, thanks to her skill and connections. In 1916, she was commissioned to photograph the coronation of Kaiser Karl I (the last ruler of the Austro-Hungarian Empire), and to then photograph Archduke Ferdinand and his five daughters (difficult as it was to squeeze them all into one frame). Kallmus’ relative, the famous actress Rosa Bertens, (she had starred in a play by August Strindberg) became her liaison to the cross-pollinating world of the arts around Vienna’s Secession. Before long she found herself inside a circle of undeniably brilliant singers, composers, dancers, actors, writers, and painters—from Karl Kraus and Arthur Schnitzler, to Alma Mahler and Alban Berg, to the sex-crazed meshugeneh in his throwback mystical toga (he fathered 14 children without ever getting married) who caused Ronald Lauder to build a museum complete with a nutty faux-Viennese period coffee shop on Fifth Avenue, catty-cornered to the historically well-endowed Metropolitan Museum of Art: Gustav Klimt. By the time, d’Ora arrived in Berlin and Paris, her client list had grown extensively to include virtually everyone who was anyone, from Dietrich on down.

Unlike Berber, or Neil Young’s Johnny Rotten, d’Ora didn’t burn out and fade away. She was a survivor. When the brown shirts rolled in to Paris in their noisy tanks in 1940, she closed shop and hustled down toward the Riviera. There, she managed to hide out in a cloister in La Lanvese, and then in an old farmhouse in a little village in Ardèche. It was not too far from where she had vacationed with her family, at age 23, on the Côte d’Azur, which is when she bought her first Kodak Brownie box camera—circa 1900, the same year Eastman Kodak rolled out the affordable snapshot, more-or-less inventing the concept of amateur photography.

D’Ora was lucky to survive, but her sister and other members of her extended family who are said to have underrated the threat of the Nazis, were not so lucky. Her sister was gassed in the Chelmno extermination facility.

After the war, d’Ora returned to Paris with the hope of rehatching her atelier. But times had changed and her glamorous flamboyant clients had either died, fled, or simply grown old and out of fashion. The party was over.

D’Ora began taking pictures on the fly, without her large format camera, or fancy studio, and popularity. She was now profoundly on her own. She did continue to take occasional portraits of aging stars like Colette (who looks like a whittled ventriloquist’s puppet with a dehydrated bush of hair about to go up in flames). She also documented hopeless German refugees on the run to nowhere, with the deadpan of Lee Miller, journalistically exposing the world to a very rude awakening indeed.

Over time, an even more visceral body of work began to emerge—images of grotesque morbidity conveying the dehumanization she’d experienced. These were pictures taken inside slaughterhouses of butchered animal parts. In her diaries from the 1940s she compared the fate of Jews to livestock moving down an assembly line of industrialized murder.

One picture of five cow hooves leaning up against a wall reads like a poem written from rock bottom.

Madame d’Ora’s career was brought to an end by a motorcycle accident in 1959, which left her mentally disabled. She returned to her family home in Austria, the house that had been forcibly sold under the Nazis and later returned. She died there in 1963.

Jeremy Sigler’s latest book of poetry, Goodbye Letter, was published by Hunters Point Press.