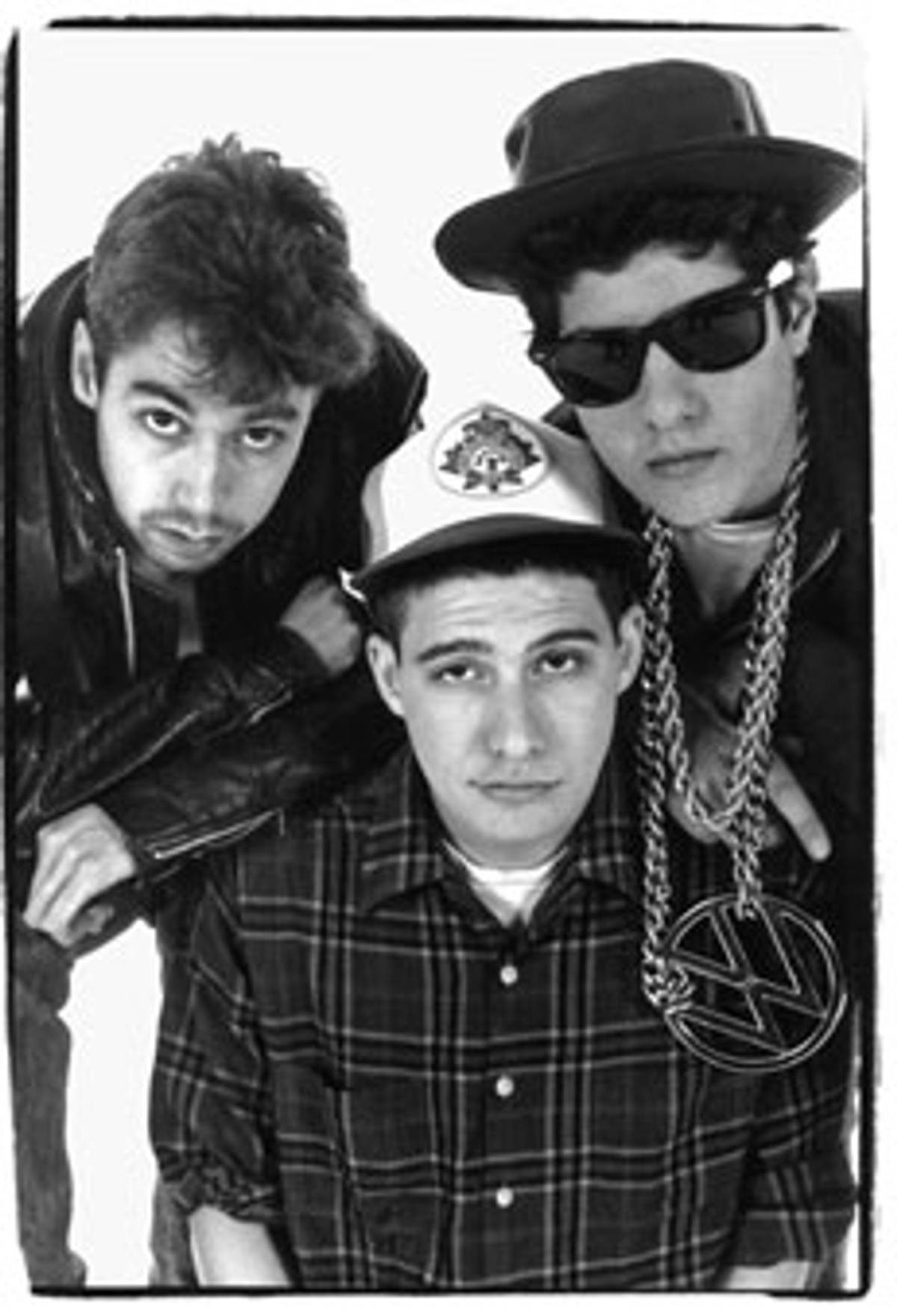

Back in 1994, I found myself entrenched in New York’s underground hip-hop scene. Despite having been born middle-class and Jewish in the Canadian cowtown of Calgary, I considered myself as close to a rap maven as an Ivy League white boy could get. One day I had a newspaper assignment to profile Alan Light, a young music journalist who’d just been installed as editor in chief of Vibe. I was half-dreading the interview. Soft-spoken and erudite, Light didn’t immediately strike me as a dyed-in-the-wool hip-hop aficionado, but I was impressed by his breadth of knowledge. He was downright encyclopedic on MCA (Adam Yauch), Mike D (Mike Diamond), and King Ad-Rock (Adam Horovitz). Turned out he’d written a senior essay at Yale titled “Rhymin’ and Stealin’: The Beastie Boys Phenomenon 1987.”

Like a generation of fans, Light saw in the Beasties some kind of revelation, an invitation to join the hip-hop party. “I had the overwhelming sense of, ‘My God, that could be me and two of my friends so easily,’” he told me. “Here were three Jewish guys, the same age as me, hearing the music and saying, ‘Okay, we’ll do it.’”

The guardians of the rock pantheon may groan, but the comparison isn’t that farfetched. Once beer-guzzling louts and wannabe CBGB punk-rockers, the Beasties have shown a growth in musicianship and philosophy that does stand, within the hip-hop context at least, as comparable to the Beatles. From the groundbreaking production of Paul’s Boutique (1989) through Awesome: I Fuckin’ Shot That!, a Madison Square Garden concert captured entirely by fans with Hi-8 digital cameras, the band has never followed a formula.

While Lennon and McCartney didn’t mask their Liverpudlian accents, for more than a decade the Beasties’ references to their Jewish background were oblique and passing, like the davening Hasid in the “No Sleep Til Brooklyn” video. It was only in 2004, on To the 5 Boroughs, that they decided to come correct. “I’m a funky-ass Jew and I’m on my way,” boasts Ad-Roc. “And, yes, I gotta say fuck the KKK.”

But even in their Fila and do-rag days, the Beastie Boys had the chutzpah to flow like themselves, never mimicking Melle Mel or Kool Moe Dee. Bill Adler, Def Jam’s first director of publicity, once pointed out to me that only one of the Beastie Boys styles his vocals like a conventional black rapper. “The other two are more or less doing a self-conscious parody of a whiny Jewish sensibility.”

Darryl “DMC” Simmons recalls his first impression in Skills to Pay the Bills. “The thing about ’em was they were so real. It wasn’t just a bunch of white guys faking just to be down with hip-hoppers or just trying to play a role.”

* * *

Hip-hop is just an incarnation of the blues. The exaggerated sexual boasting, celebration of the criminal outlaw, depiction of women as lascivious, cunning and treacherous—all may indeed, as Stanley Crouch never ceases to point out, be indicators of a moral vacuum among African-American youth—but they also derive straight from the Delta bluesman’s lexicon. And like the blues, more than any other genre of pop music, hip-hop demands autobiographical storytelling rooted in streetwise authenticity. Eminem has dysfunctional trailer-park roots, but the prerequisite doesn’t dovetail well with the comfortable middle-class backgrounds of most white rappers.

Over the years, various acts have looked to Jewish history to infuse their work with a sense of pathos, oppression, and struggle. The Los Angeles-based duo Blood of Abraham released Future Profits (1994), an album filled with Hebrew samples, and shot a video at the Western Wall. “Never Again,” a somber and defiant meditation on the Holocaust by Remedy (born Ross Filler), appears on the platinum-selling 1998 Wu-Tang Clan compilation, The Swarm. The trouble with Hebrocentric hip-hop (not to be confused with the forgettable camp of 2 Live Jews, M.O.T. and 50 Shekel) is that however well-intentioned and heartfelt, the Jewish-themed lyrics often come across as inorganic, heavy-handed, overly earnest.

The only Jewish rapper with the skills to challenge the Beastie Boys was MC Serch, a founding member of the group 3rd Bass. Awkward and obese, eschewing contact lenses for oversized nerd specs, Serch called himself the “baddest whiteboy to ever fuckin’ touch the mike.” Born Michael Berrin in Far Rockaway, he was proud to be Jewish but also spouted Afrocentric rhetoric, sported Negro League baseball uniforms, wore his hair in an exaggerated homeboy fade, as if constantly proclaiming: Check out my ghetto pass. I’m the blackest white boy around.

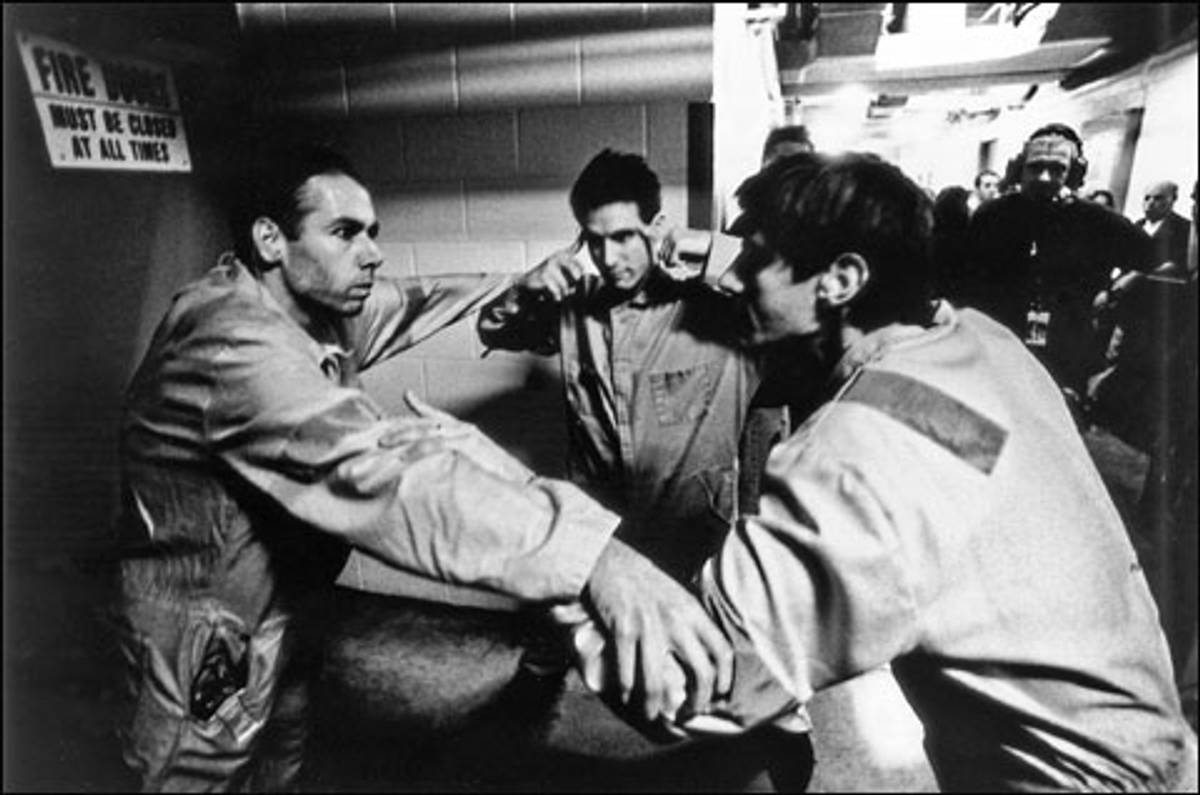

Serch and his rhyme partner, Prime Minister Pete Nice (the Columbia-educated Peter Nash), accused the Beastie Boys of “violating” hip-hop culture, and on their much-admired The Cactus Album (1989) they attacked “The Beast” as “silver-spoon-havin’, playwright-posin’” frauds. The Beasties were never much for battling, but these jibes hit a nerve. In response, the Beasties dissed MC Serch in the song “Professor Booty”: “one big oaf who’s faker than plastic/A dictionary definition of the word ‘spastic.’”

Today even the most devoted 3rd Bass fans have to acknowledge that the group was bush-league—Herman’s Hermits?—next to the Beasties. But for a hot minute before 3rd Bass went after other white rappers like Vanilla Ice, Everlast and, eventually, each other, the Beastie Boys-3rd Bass beef was big news in hip-hop. (MC Serch, now hosting a morning radio on WJLB-FM in Detroit, admits to Light that he thinks the Beastie Boys are “brilliant orators and brilliant storytellers.”)

Call it envy or overcompensation, it’s a story as old as the first white wolf creeping into a juke joint, fancying himself the coolest Caucasian in existence. And like Dorian Gray in the attic, he recoils at his own horrifying likeness. Remedy of the Wu-Tang Clan has said he feels more “prejudice from other Jews in the industry,” than from black rappers. But that’s the plight of all hipsters, the new “breed of urban adventurers” Norman Mailer described in his 1957 essay “The White Negro.” “Like children, hipsters are fighting for the sweet,” Mailer writes. “Unstated but obvious is the social sense that there is not nearly enough sweet for everyone. And so the sweet goes only to the victor…the man who knows the most about how to find his energy and how not to lose it.”

Or failing that, we lose the sweet tooth, kick the hipster habit, grow up. Over 40 myself now, I find it hard to listen to the ultramaterialistic, cookie-cutter rap on Hot 97 or BET. I’ll blast the Roots, Kanye, or classic Rakim now and then, and I still contribute the occasional piece to hip-hop magazines. But I’m focusing on a broader canvas. Alan Light, now a consultant to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, has also hopscotched the rap cul-de-sac. A few years back, he launched Tracks, a monthly “music magazine for adults,” featuring Randy Newman, Lucinda Williams, and Wilco. (The print version is currently on hiatus, but Tracks maintains a website.) We’re both fathers of young children.

The Beasties, nearly 40 themselves, are family men, businessmen, environmentalists, peaceniks. The former frat-boy boors headlined the Tibetan Freedom Concerts, meditated with the Dalai Lama. MCA wears the full gray beard of Methuselah. Ad-Roc no longer tunnels through hotel floors. It’s hard to trash a Holiday Inn or write a pissed-off battle rhyme when you’ve just finished doing yoga.

Douglas Century is the author of Street Kingdom: Five Years Inside the Franklin Avenue Posse and co-author of the New York Times best-seller Takedown: The Fall of the Last Mafia Empire. He also wrote Barney Ross: The Life of Jewish Fighter, a biography in the Nextbook Press Jewish Encounters book series.

Douglas Century is the author and coauthor of numerous bestselling books including Hunting El Chapo, Takedown, Under and Alone, Brotherhood of Warriors and Barney Ross: The Life of a Jewish Fighter, a biography in the Nextbook Press Jewish Encounters book series.