My Socialist Uncle Munia

A visit from a long-lost relative brings memories from Ukraine, and more than a few misadventures

One memory-mollifying afternoon during the last week of July 1987, I returned to Ladispoli from Rome’s Round Market with my East German-made checkered shopping bag on wheels, only to find my Israeli great-uncle Munia sitting in our kitchen and having tea with toast, jam, and ricotta cheese. He got up to kiss and hug me, pliers of his bony hands clenching both my shoulders. I felt his unshaven cheekbones against my lips.

“Sit down, my boy. Have a glass of tea,” Uncle Munia said as though he had known me for eternity.

There was something disarmingly adorable but also encroaching about our Uncle Munia, something I associate with the word mishpocha. We hadn’t been expecting Uncle Munia until the following day. He had sent us a telegram: “my dears arriving rome day after tomorrow yours munia.”

My parents and I had left Moscow in early June and come to Italy by way of Vienna. Our whole lives in transit, we had been staying in Ladispoli for about three weeks, and we weren’t sure when our U.S. refugee visas would come through.

“As if he had waited for us to make up our minds about going to America,” my mother said after the downstairs signora had delivered the telegram from Uncle Munia, ashes flying off her slender cigarette onto her purple peignoir.

“He’s not like that, my Uncle Munia,” father said. “He’s an idealist. He used to be in the Socialist International. And he worked with the Arabs, in the desert.”

So he did.

Instead of spending the night at an airport hotel at Charles de Gaulle, Uncle Munia had made an earlier connection to Milan and from there flew to Rome, eager to see us. His suitcase toured Italy for another two days, but Uncle Munia had a piece of light hand luggage with him, containing a toiletry kit and denture case, a change of underwear, an old Baedeker, a Soviet novel, and a camera. He was a champion of traveling light, but he brought with him weighty family histories and an unnerving feeling of inescapability.

An “uncle from Israel” was a legendary cliché of our Soviet refusenik years. When submitting an application to emigrate, people would sometimes fictionalize stories about their mother’s or father’s long-lost and now miraculously found Israeli uncle or aunt. But ours was a real uncle, one of my late grandfather’s older brothers, who had been living in the Land of Israel since the 1920s.

Some of the things we had known about him seemed unimaginable to us back in Moscow. A left-wing Socialist (he called Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir voniuchii karlik “a stinking dwarf”), a speaker of Arabic and friend of the Bedouins, an atheist and an eccentric, a lover of Russian literature and erotic art, Uncle Munia was now sitting in the kitchen of our Ladispoli rental apartment, having come to Italy to embrace us. Or perhaps even to talk us into going with him to Israel, where the family had lined up a medical job for my father, a writer-doctor, and where the government supposedly sponsored publication of repatriates’ literary works.

By the end of Uncle Munia’s visit to Ladispoli, we had filled gaps in our family history, adding his story to what we already knew. Munia and his two younger brothers, my paternal grandfather, Pusia, being the middle child, were all born between 1907 and 1911 in or around Kamianets-Podilskyi, then an important regional center in southwestern Ukraine. Their father’s first wife had died, leaving him with two small children, and soon after he married a woman of progressive beliefs who was already 25, practically an old maid, and came from a poor Jewish family.

As far as I can tell, Uncle Munia didn’t get along too well with his father, a mill owner who respected Jewish traditions while not shunning modernity. After his bar mitzvah Uncle Munia never again went to synagogue, and when we met him in Ladispoli, he came across as an enemy of religion and its web of institutions.

Uncle Munia matured in the years 1917-1921, a time in Kamianets-Podilskyi when regimes and occupation forces kept changing: Provisional Government, Bolsheviks, Ukrainian Directoriat, General Denikin’s Volunteer Army, Simon Petlyura’s Ukrainian units, Polish troops, and Bolsheviks again (this time, to stay). By 1922 Uncle Munia had become a socialist-Zionist. He developed an interest in agronomy and agriculture. In 1924 he sailed from Odessa on board the Novorossiisk, bound for Jaffa. He never laid eyes on his parents again, nor on three of his four siblings. In the late 1970s he saw his youngest brother Abrasha on a visit to Hungary.

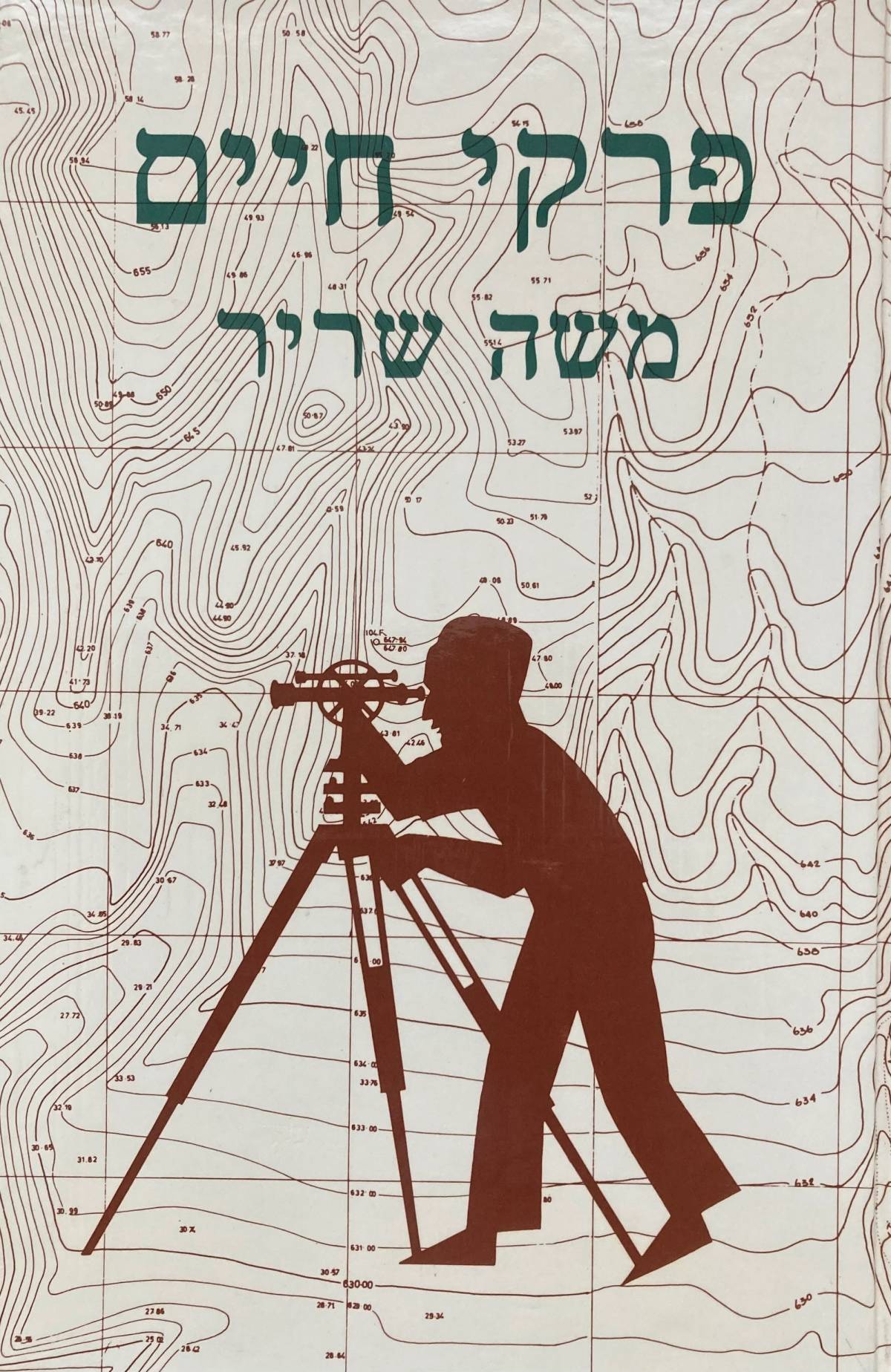

In the Mandate of Palestine Uncle Munia worked in kibbutz Afikim in the Jordan Valley. He trained and eventually started working as a land surveyor. He married a Jewish woman from Ukraine; their two sons were born in the 1930s, his youngest close in age to my father. In the late 1930s, for his leftist activism Uncle Munia was fired from the British Department of Land-Surveying in Palestine. Much as he abhorred the idea of starting a business of his own, he had a family to support, and he opened a private land-surveying office. He spent months working in the desert. He rode camels, dressed in Bedouin garb. He was scrupulously honest and enjoyed a solid reputation with both Jews and Arabs. And he was also known to underbid and to pay himself last. The land-surveying business didn’t become profitable until the 1960s.

Uncle Munia’s first wife, Rusha, died in the 1970s, and he remarried. His second wife had also come from Ukraine in the 1920s. His older son never accepted the second marriage, but Uncle Munia outlived his second wife, too. When we met him in Ladispoli, Uncle Munia was single again—single and still hungry to live.

My father had been corresponding with Uncle Munia since about 1978, when Munia wrote to him against the wishes of his youngest brother, Abrasha. There had been bad blood between my father and Uncle Abrasha ever since my grandfather’s death and funeral. The correspondence continued, despite efforts by Uncle Abrasha to portray my father as a ruffian. And about every four to five months we would receive from Tel Aviv a hefty envelope with a long letter and pictures. I can only wonder how many the KGB had stolen for its fathomless literary archives. The letters, at times bordering on a graphomaniac’s outpourings and chapters from unfinished autobiographies, described our extended Israeli family and minutiae of Uncle Munia’s life. Uncle Munia also sent us packages with German-made rubber-sole shoes and denim jeans. Some of his letters carried outlandish requests, such as to find out if any relatives of his best childhood friend, Mikolka, were still living in Podolia. In the others he preached vegetarianism to us with such zeal that we wondered if Uncle Munia had any idea how hard it was to procure even basic staples in a Soviet food store.

In the letters he came across as a staunch radical, as unprudish and self-denuding, and also as a romantic, exactly as I found him in Ladispoli as we shared an afternoon tea and a snack of bread, ricotta cheese, and apricot jam. He treated us with such familiarity that it felt like the family had never been split after Munia’s departure in 1924. He immediately insisted that not only my father—his nephew and son of his “beloved brother Pusia”—but also my mother and I address him with the informal ty and drop the patriarchal “uncle.”

“I used to play soccer with your dear papa, back in Kamianets,” Uncle Munia corrected my mother as she tried to resist a breach of protectively formal Russian grammar. “He was a tall and handsome fellow, a bit narrow in the shoulders, but that was fashionable in those days. Lanky. Your son looks quite a bit like him.”

“Kamianets” was how its natives and their descendants lovingly referred to Kamianets-Podilskyi, the town of both my grandfathers’ childhoods and youths. I can well remember my mother’s father smiling dreamily when he mouthed the word “Kamianets.”

My father’s family had been living in the environs of Kamianets-Podilskyi for three generations. Situated near the border of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Kamianets was the capital city of Podolia province. On the eve of World War I, nearly half of the city’s population, about 23,000, was Jewish. By the 1930s the Jewish population had dwindled by half. In August 1941 Kamianets became one of the largest killing sites, where over 20,000 local Jews and Jews deported there by Hungarian authorities were murdered by bullet. Only 3,000 Jews of Kamianets had survived the Shoah and returned. During the Soviet period Kamianets grew more provincial and unimportant, and it was subsumed as a district center into Ukraine’s Khmelnytskyi province, the very name of which brings memories of atrocities committed against the Jews by the troops of Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytskyi in the 1640s.

“My boy, have you been to Kamianets?” Uncle Munia asked me as we got up from our tea.

“No, I haven’t,” I answered, a bit on the defensive. “Didn’t have the occasion. There was no family left.”

“And what a beautiful town it is! The Smotrich, its looping banks, the old Turkish fortress. ... I would like to go back and visit. My Ukrainian used to be much better than my Russian. And my best friend Mikolka—"

“Uncle Munia,” father interrupted him. “We did try to locate his family. We wrote to the town clerk, but we couldn’t find anything.”

“Ah,” Uncle Munia sighed. “Why have you never visited? Do you also believe, like those knuckleheads of ours, that Ukrainians are antisemitic? Such hogwash!”

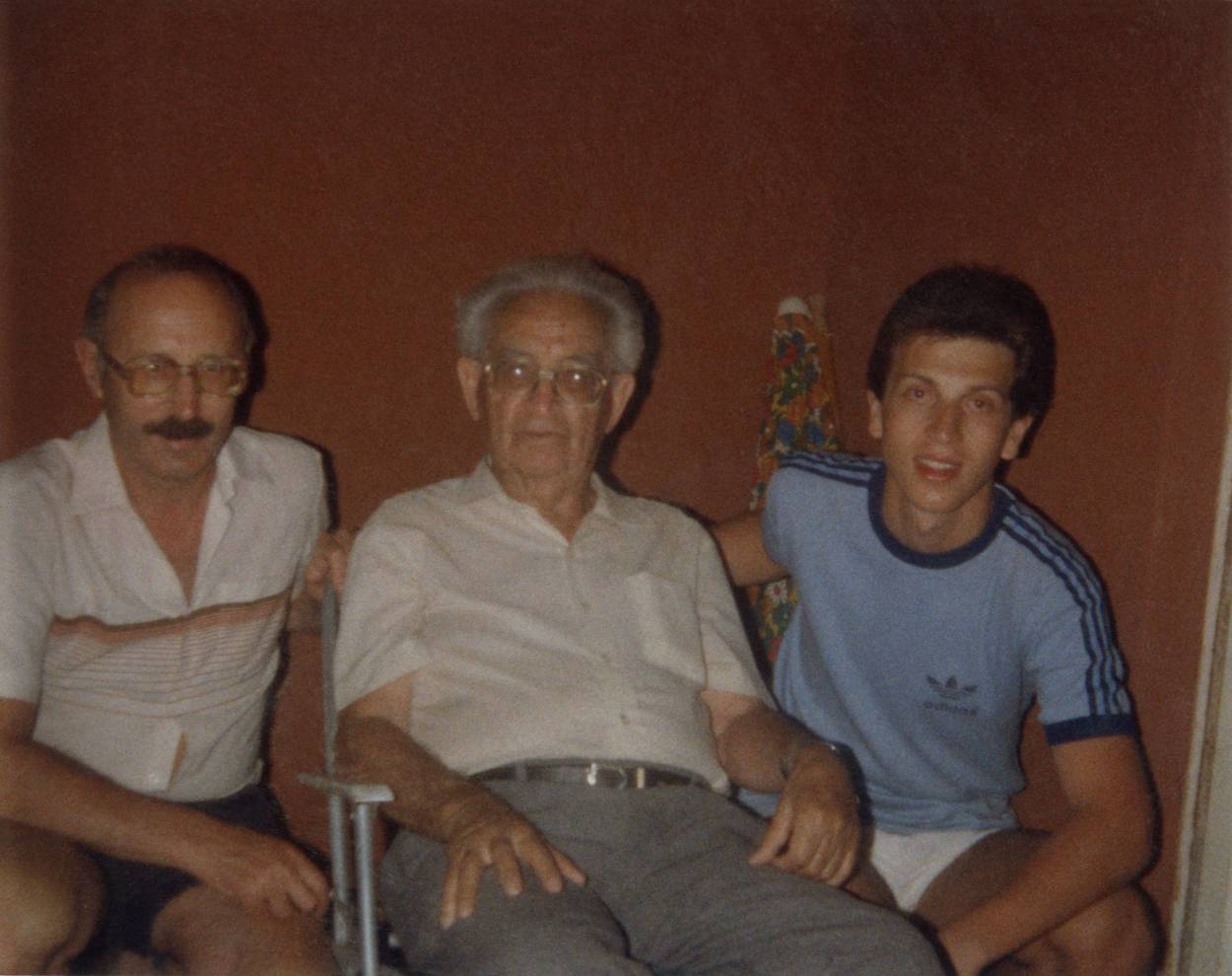

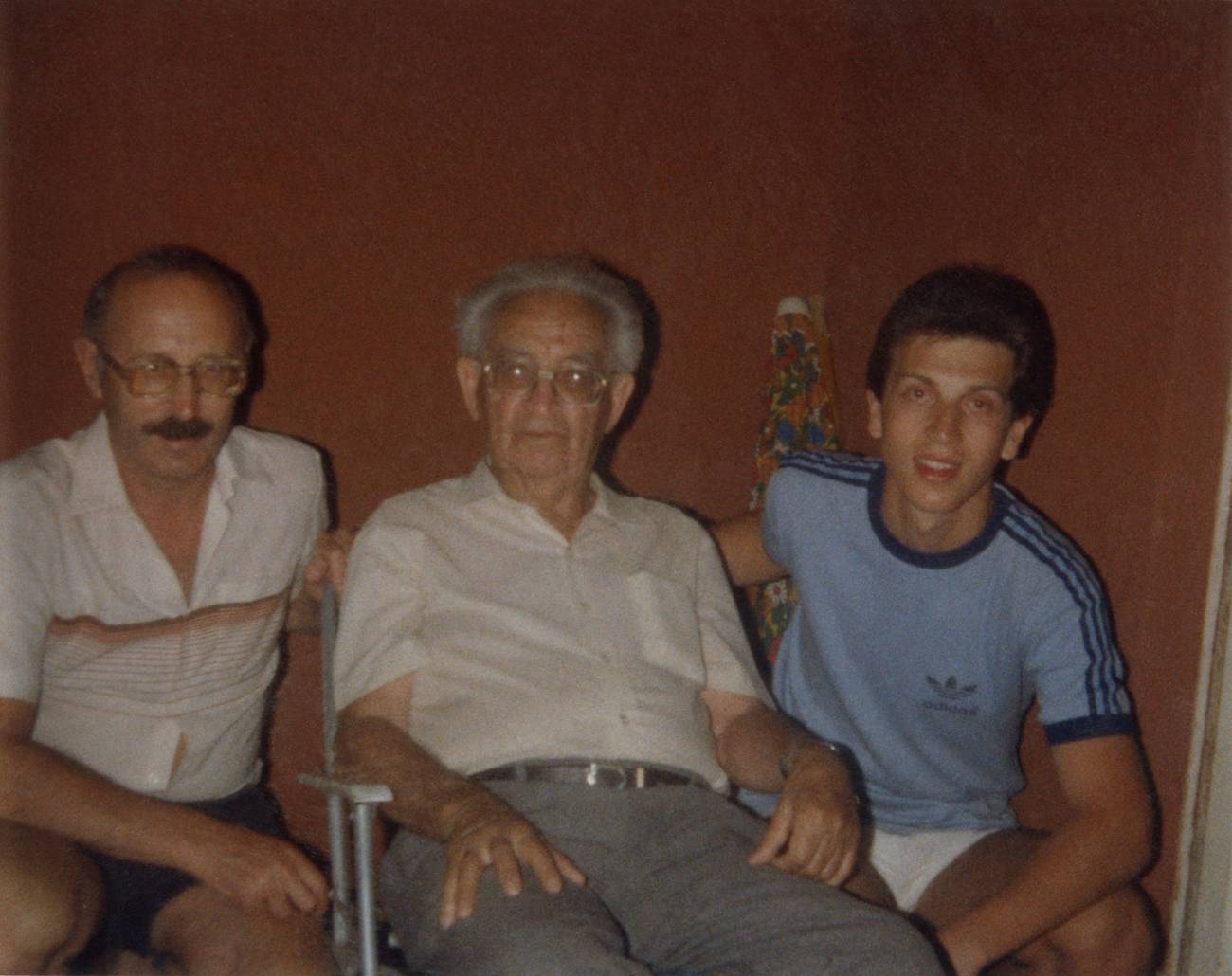

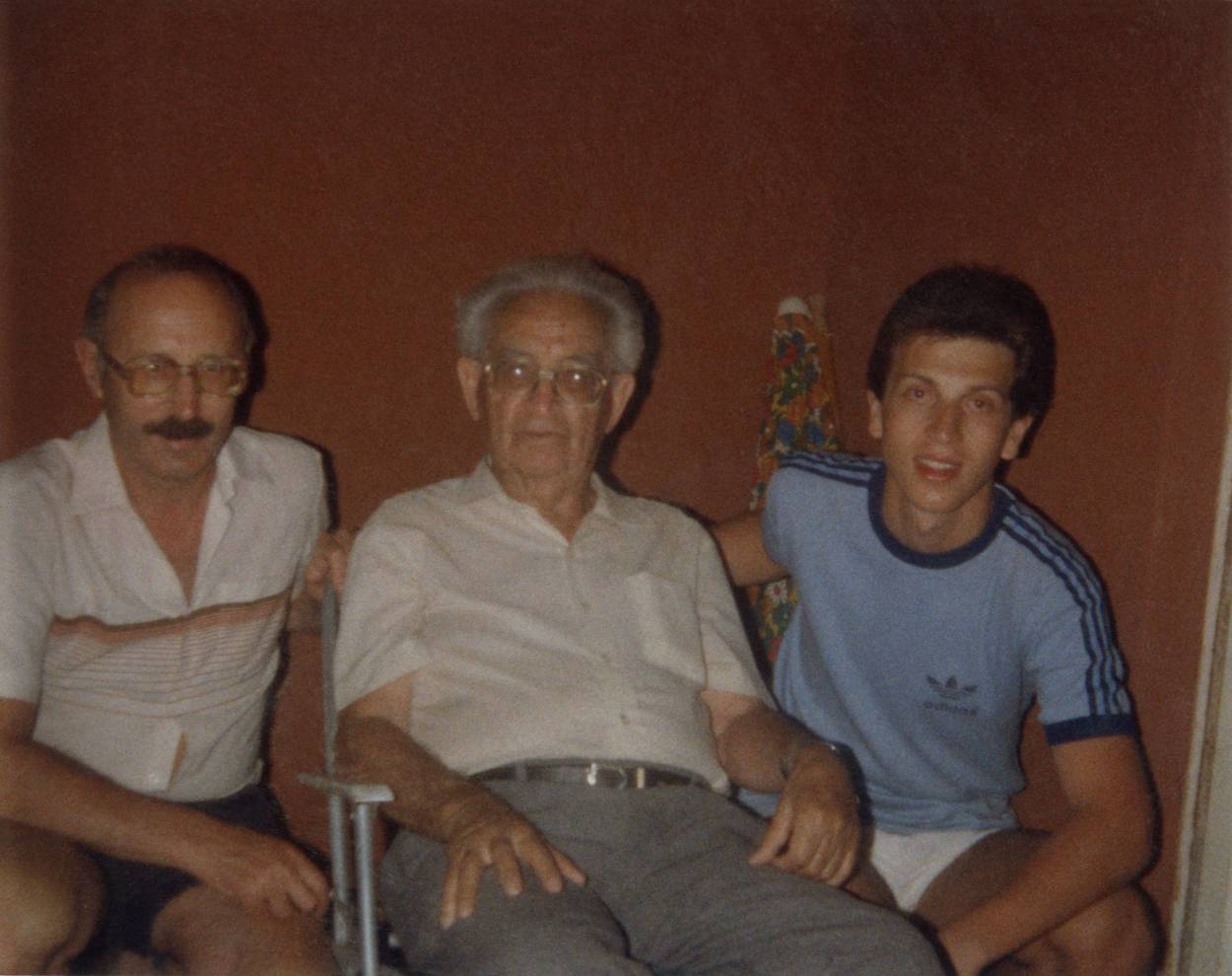

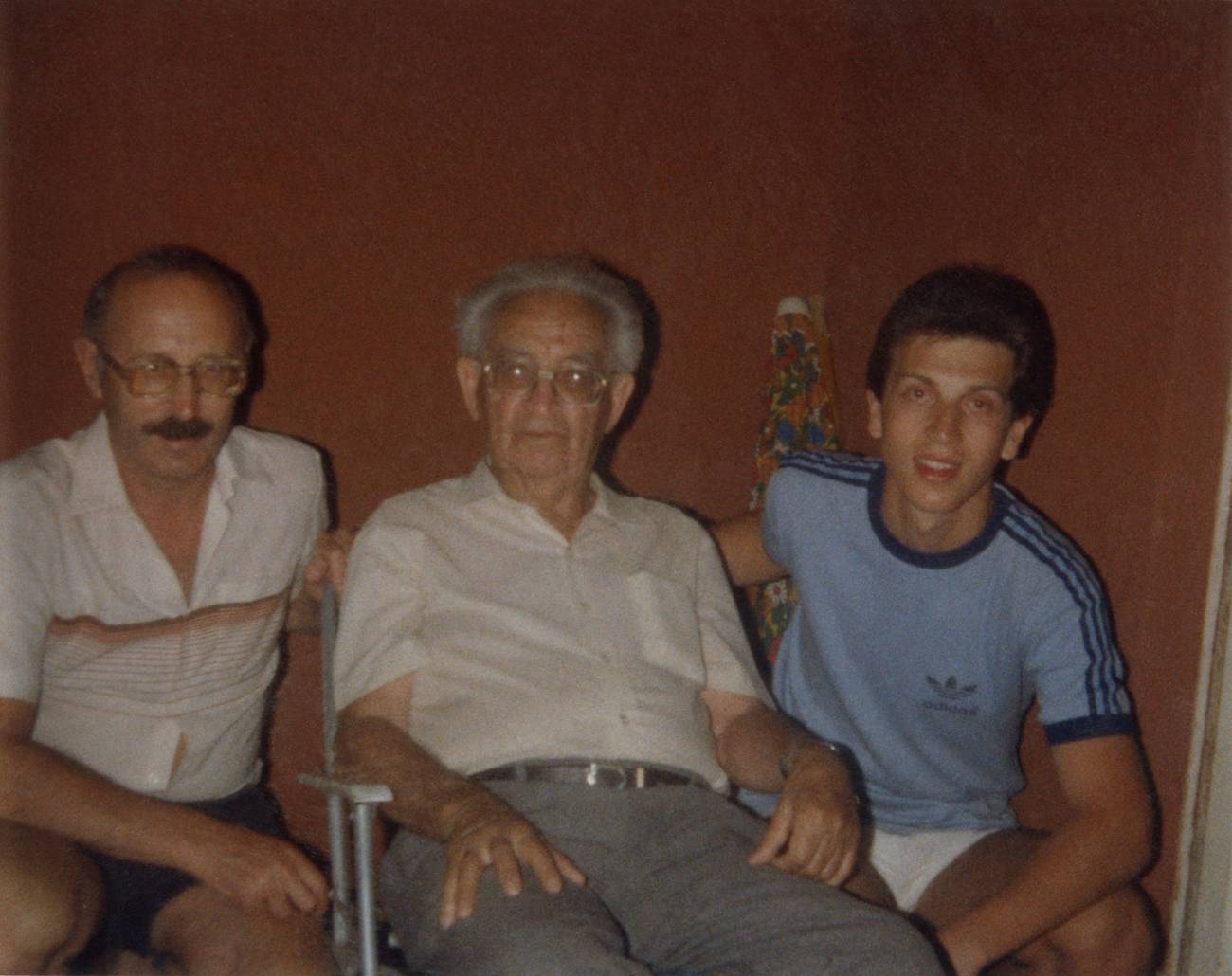

This is a good moment to describe Uncle Munia. He was about 5-foot-7, with a lion’s mane of hair. Very dry, but still very animate—like a mountain river in summer that still remembers itself turbulent and full of spring torrents. The shape of his face and his distinguished, beak-shaped nose were shaped much like those of all cousins, aunts and uncles, and nieces and nephews on my paternal grandfather’s side. However, Uncle Munia’s skin had acquired the permanent cinnamon stain of the desert. When we strolled on the boulevard in the days following his arrival in Ladispoli, a refugee couple stopped to comment how much the grandfather, father, and son all looked alike; they had assumed that Uncle Munia was my grandfather. Uncle Munia was 81 when we met him, and under the metal frames of his unfashionable spectacles his young, hyperalert eyes led a convivial life of their own. He spoke excellent Russian, a bit outmoded and only slightly accented in the manner of educated Ukrainian Jews, and he sometimes used English words to refer to objects he must have first encountered after leaving Russia. For instance, he said gelikopter instead of the native Russian vertolet. There was something unexpectedly modern and progressive to this Israeli uncle of ours. And he wasn’t even trying to shock us with his revolutionary exhibitionism of ideas.

Before we had time to cover the most basic of the family terrains, Uncle Munia announced to us that it had always been his dream to visit Pompeii and see the famous frescos. He had with him an old Baedeker guide of Italy, and he opened it to the section on Pompeii and showed us a reproduction of a fresco from a lupanarium.

“Look, look, such sophistication,” Uncle Munia said, pressing two fingers to the deeply arched back of the woman in the picture. “They knew more about love than we’ll ever know,” he added, turning to my mother, who was slicing a huge blush peach.

“I want to stay here a couple of days, and then I want to take you all to Pompeii and also to Sorrento,” he explained, summing up his plans. “Sorrento and Capri were Maxim Gorky’s stomping ground. Did you know that, my dear boy?” Uncle Munia asked me.

Mother and Father persuaded him to rest a bit before an evening stroll and dinner. Tumbling in and rising out of the delayed siesta in the living room that I would share with Uncle Munia for the next few days, I heard him shuffling books, newspapers, and old issues of Italian and Russian magazines spread out on the coffee table. When I woke up, Uncle Munia was no longer in the room. The door to my parents’ bedroom was still closed, and after washing my face I ambled to the kitchen, where I found him, clean-shaven and beaming, violently scribbling something in a pocket notebook. Under a Chekhovian ashtray on the kitchen table I saw three crisp hundred-dollar bills—a green oasis amid the table’s arid surface.

“What’s that, Uncle Munia?” I asked.

“A troika of wild horses,” he sang out, clicking his fingers like a gypsy singer. “Wake up your lazybones parents. I’m inviting you all out to dinner, to celebrate our reunion.”

Looking for a restaurant on our first night with Uncle Munia turned out to be an ordeal. At first he made us stroll on the boulevard to work up, as he put it, a “healthy appetite.” Then he dragged us around half of Ladispoli’s central quarter, studying menus, examining the ambiance, and inquiring about vegetarian options. “Does your red spaghetti sauce have any meat?” Uncle Munia would ask, plunging my father into a fit of embarrassment. Or, “Can we have that table facing the fountain?” (pointing to what was inevitably a reserved table). Or else, “Do you have a nonsmoking section?” (in the Italy of the 1980s?!). And Uncle Munia did not seem to mind having to look further. Silver-blue hair shining in the setting sun, slacks and checkered shirt fluttering on his slight frame, Uncle Munia led his tired relatives all around the main piazza and the commercial strip and then down Via Ancona, until we finally found refuge in an open-air restaurant just around the corner from our apartment. We’d come full circle. It was an Italian restaurant with Chinese lanterns where music played at night and a Tom Jones lookalike sometimes performed standards. For some reason Uncle Munia liked the place, and after switching two or three times we finally settled at a table that was “not too close to the street or the music, but with a view of the boulevard.”

“It’s too hot to guzzle red wine, and beer is for people with no taste,” Uncle Munia declared. My poor father had to give up the hope of a drink.

The waiter brought us a sweating carafe of water, some bread, and portions of insalata verde. Uncle Munia pinched off a piece of bread, chewed on a lettuce leaf, and leaned back in his chair.

“Now I need to tell you something,” he said. “You know I don’t like to beat around the bush.”

“What’s the matter, Uncle Munia?” father asked, feeling trapped.

“Nothing’s the matter. Why are you all getting so tense?” Uncle Munia replied, putting another lettuce leaf in his mouth and chewing with maddening slowness. “I just wanted to tell you that I don’t resent you for not going to Israel. Once again, let me say that you’d feel at home there, but I don’t resent you. America is very nice! I’ve been there five times, to Washington, New York, Boston, Chicago, San Francisco—all great and fine cities. But it’s an emotional desert. People are too individualistic.”

We sat silently, backs pressed to our chairs.

“You’re my late brother’s son,” Uncle Munia said, turning to my father. “You’re practically like my son genetically, so I accept your decision. But let me say it one more time: If you change your mind, it’s not too late.”

A minute of silence felt like eternity in the outdoor restaurant, where music played and waiters scurried around like frenzied squirrels.

“OK, I just needed to get it off my chest,” Uncle Munia said jovially, clapping his hands. “Let’s not fight, my dears. Let’s eat and celebrate our reunion.” He lifted a glass of water, licked his lips as though preparing to offer a toast, but then put the glass down.

“There’s one more thing,” said Uncle Munia. Something inside me felt like a huge toad trying to leap out.

“I wanted to explain something to you, my dears, because this has come up in our correspondence, when you were still in Moscow. And already once today, when we were having tea. It’s about my political beliefs.”

That was vintage Uncle Munia: choosing salads one minute, confessing communist sympathies in the next.

“I’ve already written about it in my book Notes of a Land-Surveyor, in Hebrew, and now I would like to translate it into Russian. For now, you’ll just have to listen to my story.”

Mother, father, and I laid down our forks and knives as a sign of surrender.

“I came to Israel—you probably know this already—in 1924,” he began. “I had left Kamianets because I couldn’t stay there. I was in a youth Zionist organization. We were all idealistic boys and girls, and a Jewish acquaintance whose son worked in local law enforcement had tipped off my father that there was a signed warrant for my arrest. In haste I fled to Odessa, where we had cousins. I was 18. I didn’t know what I wanted to do. My great passion was reading. I had five or six notebooks full of drafts. I wanted to write about working people, to be a Jewish Gorky. It sounds childish today, but back then ...

“In Israel I spent some time in an agricultural commune near the Sea of Galilee. Life was very hard. I missed home and my family. I still wasn’t sure in my heart why I was there. In 1926 I joined the Department of Land-Surveying. The office was run by the British. The bosses were disciplined workers with a colonial mentality.”

The band started playing “O Sole Mio.” Uncle Munia had barely touched his food. Where does he get his boundless energy? I remember thinking.

“Very soon,” Uncle Munia continued with his story, “I was branded a left-winger and Soviet sympathizer. I was openly critical of the British and what they were doing in Palestine. The conniving. The pitting of Arabs against Jews. Broken promises. The White Papers. My bosses at the Department of Land-Surveying had difficulty making sense of my politics and also my friendships with Arabs. I was seriously studying Arabic. I didn’t fit common profiles.”

When our pasta dishes arrived, Uncle Munia wrinkled his brow, gave the waiter a stern look, and asked if the singer could sing a little softer. The waiter spread his arms, mumbled something along the lines of porco miseria, and left.

Uncle Munia continued. “I was already married and we already had a son. We were living in Tel Aviv, and I was still thinking of repatriating. In 1934 I petitioned the Soviet Consulate in Istanbul to allow me to return to the USSR. My petition was denied—otherwise who knows how things would have turned out? We might not be sitting here today.”

Uncle Munia finally tasted his penne with tomatoes and zucchini, too impatient to eat more.

“So I stayed, and we were raising our two boys. But I continued to read Soviet papers and magazines. I subscribed to Ogonyok, the weekly glossy magazine, and my younger son actually learned about Russian art from the spreads they used to print. I went to see Soviet movies at Eden Cinema, and I followed the current events. It still had a grip on me. Then, in 1938 I was fired from the Department of Land-Surveying. They had found a convenient excuse—‘staff reduction’ they called it—but it was for my left-wing political orientation all right.”

“Uncle Munia, you’re not eating your food,” said mother.

“Drop the uncle part, will you?” Uncle Munia said to my mother. “The food will wait. It’s not interesting.” (Uncle Munia used the words interesting and not interesting all the time in place of “good” and “bad.”) “I just want to finish with politics, and then we can drink and laugh like children of doubt and disbelief,” added Uncle Munia, appropriating Dostoevsky.

“What I wanted to explain to you is that it took me longer than many even among my comrades to shed illusions about the USSR. Not even after the death of Stalin. And still I couldn’t quite believe the things we were hearing. In 1968 a second cousin of mine—you probably didn’t know her—came to Israel from Odessa. She was the first relative to leave since the 1920s. I spent a week interrogating her. I exhausted her with questions about life there. She was an obstetrical nurse, a very fine and sane person. She never married, and she died of cancer just a few years after coming to Israel. I had known her since childhood, and seeing her and talking to her weaned me from my last illusions. But I still miss Kamianets and Ukraine, still today, after so many years. Terribly.”

Uncle Munia reached for a large, sky-blue handkerchief and wiped the corners of his eyes. The waiter, who came to offer us coffee and dessert, fractured the silence that had descended upon our table.

With the bill arrived the most dramatic moment of the evening. First Uncle Munia put on his spectacles and examined the contents of the bill, line by line, like a schoolboy still learning to read cursive. Then he removed a pen from his breast pocket and proceeded, right under the stare of the apoplectic waiter, to cross out items. He crossed out a line and then paused, lifting his head and commenting: “What cover charge? Bread and water should be free with dinner.” Then he crossed out another line and exclaimed: “What cheese? You think we should be paying for the crummy piece of cheese you brought for the four of us? In any case, in civilized restaurants salads come free with entrees.”

The headwaiter and two other waiters had now joined our server in front of the table, and the four of them argued with Uncle Munia in some transnational restaurant argot, interrupting each other.

“Uncle Munia, I beg of you, please stop,” my father moaned.

Undeterred, Uncle Munia added up what he thought the bill should have been, counted out the money, and put it on a little plate on top of the severely redacted bill.

As we walked out of the restaurant, the waiter yelled, “Don’t come back here, thieves.”

Uncle Munia stayed with us in Ladispoli for six days, and they felt like six months. Draining, eye-opening days, doused with trivia.

“Answer quick, my boy, what’s the difference between a village (derevnia) and a small rural town (selo)?” Uncle Munia would ask as we walked back from the beach toward siesta and the promise of quiet.

“You got me there, Uncle Munia,” I would reply.

“See, you don’t know, and I still remember: A selo must have a school and a church,” he delivered, triumphantly.

For me, seeing Uncle Munia was like being able to connect the lines of our family past. And it must have been the same for both my mother and father. Uncle Munia had known their fathers before my parents knew them. This is why being with him in Ladispoli finally felt like moving from a Euclidian narrative world, where stories of our family in Ukraine and Russia and stories of our relatives in the Land of Israel ran parallel to each other without ever intersecting. In the Lobachevskian world where we dwelt during Uncle Munia’s visit, the parallel lives had suddenly and unthinkably intersected.

But the excitement of intersecting family storylines came at a price. How Uncle Munia interrogated people. And his obsession with the love life of people and animals. At the Ladispoli beach, when I had gone off to buy a gelato, he sought out Irena, then my Baltic girlfriend that never was, and questioned her about our “relations,” as he put it. He was disappointed.

Twice during his stay in Ladispoli I had variations of the same dream about looking for an oasis in the desert and running into Uncle Munia dressed as a Bedouin.

“Water, water,” I tell him in the dream, speaking in Hebrew.

“Are you a member of the Second International?” he asks.

“No, I’m not. Why?”

“The cheese in the restaurant was not interesting,” says Uncle Munia and starts singing the Marseillaise in Ukrainian.

After Ladispoli I only saw Uncle Munia one more time. He never visited us in America—he had his own reasons. Father and Uncle Munia occasionally corresponded, and they saw each other in the mid-1990s in Israel, when my parents stayed at Mishkenot Sha’ananim, an artists colony in Jerusalem. It wasn’t the same Uncle Munia, my parents later told me. Physically he was still strong, but his memory was beginning to fade.

In the summer of 1998, less than a year before I met my wife and my life changed forever, I took my last long trip as a bachelor. I was on my junior sabbatical, and I didn’t have to teach for the whole year. On the road for almost seven weeks in August and September, I had visited my dear Estonia of childhood summers, and also stayed in Poland, where Jewish memories were for sale in Krakow’s Jewish town, but only a handful of elderly Jews remained. After that I went to Israel for the first time and spent three weeks touring the country and seeing family. I found it no less than enthralling. Was it a mistake we hadn’t made aliyah in 1987? I kept asking myself.

After spending time in Haifa and Upper Galilee I made my way back to Tel Aviv. On my second day in Tel Aviv, Uncle Munia’s younger son, a painter and set designer, took me to see his father.

“Phoning Abba is pointless,” Munia’s son had warned me. “We’ll just go visit him in the morning.”

Uncle Munia was living in the same “railway” apartment building in the eastern part of Tel Aviv, where he had moved with his family in the early 1950s. He refused to go to assisted living, and a Jewish Ukrainian lady from the post-Soviet wave of aliyah looked after him. Framed by the black apartment door and wearing his signature striped short-sleeved shirt and unwrinkled trousers, Uncle Munia looked desiccated like matzos. (I’ve borrowed the metaphor from the Odessan poet Eduard Bagritsky.)

“Who are you?” he asked after we kissed and embraced.

“Uncle Munia, I’m Pusia’s grandson. Remember Pusia?”

“Pusia? My brother? What do you take me for? Of course I remember him.”

And he pulled me by the T-shirt to his den, where family photos crowded the walls. I recognized many of the faces and some of the photos. After Uncle Munia had left in 1924, his parents would paste his photo into the formal family portraits, and so his head looked bigger than the heads of his four siblings.

“See how far apart the buildings are?” Uncle Munia said proudly, opening one of the windows. “Tel Aviv’s overcrowded, you know.” And he added, “There’s a waterfall nearby.”

It turned out Uncle Munia used vodopad, the Russian word for “waterfall,” instead of fontan. There was indeed a fountain erupting out of a rock in a public garden across the street.

Russian books—classics but also paperback thrillers about the Russian mob—lay scattered all around, abandoned on the sofa, the window sills, the kitchen table.

“You see how spacious this apartment is?” Uncle Munia said. “My old friend, a famous architect, designed the interior. Yes, well. Who are you again?”

“I’m your younger brother’s grandson,” I answered.

“I have two younger brothers, which one?”

“Pusia. Do you remember Pusia?”

“Of course I do,” Munia replied as I pressed my hand to the cold wall under a framed picture where the three brothers—Munia, a teenager, his brothers Pusia and Abrasha, 10 and 9—were captured by a Kamianets photo artist who dashed his name across the right bottom corner.

But then he suddenly remembered my father and asked, indignantly, “Why doesn’t he send me his new books?”

So his memory hadn’t all expired.

Two days later, on a Friday afternoon, the youngest of Uncle Munia’s granddaughters picked me up near Dizengoff Center, and we drove through the swampy heat of Tel Aviv to fetch Uncle Munia and take him to her father’s house in Old Jaffa—the artists quarter near the sea. It was Uncle Munia’s weekly ritual to spend Friday nights with one of his sons and their families.

My second cousin was wearing a white linen dress with slits in the back. She had short black shiny hair and hazel eyes.

In the car on the way over I had started telling my cousin about Uncle Munia’s visit to Ladispoli. Uncle Munia sat silently in the back for most of the ride.

“I never learned Italian,” he finally said. “But I speak Arabic fluently.” And he said something as a way of demonstrating it.

Dinner was served in the large parlor room overlooking the Mediterranean. Prepared by Uncle Munia’s daughter-in-law, who had come from Bulgaria at a young age, the dinner had a distinct Balkan and Turkish flavor. Uncle Munia and I spoke in Russian.

“My first wife and I used Russian as a private language when we didn’t want the boys to know something,” Uncle Munia said to me. “But my older son picked up quite a bit. My younger son—just a couple of words here and there. My second wife and my girlfriends after her have all been from Russia.”

“Munia, how’s Verochka?” the artist’s wife asked Uncle Munia.

“Who’s that?” Uncle Munia asked, not one bit bewildered.

“Verochka. Don’t you remember?”

“Ah, Verochka,” and Uncle Munia turned to me and switched back to Russian. “Verochka is my girlfriend,” he explained to me. “She’s younger than me.”

The recent past had ceased to exist, but the distant past was a vast sea, on whose waves Uncle Munia still cavorted. I asked him about his youth in Kamianets and how he, scion of a wealthy bourgeois family, first became interested in socialism. Uncle Munia responded with a confession of feeling guilty for something he did—or rather didn’t do—as a young man. This was just before he left home for good. His father had asked him to come to synagogue with him on shabes, and Uncle Munia adamantly refused.

“I remember this day like it was yesterday. You understand, I’ve regretted it my whole life. I never saw my father again. I should have come with him. I should have strangled the principle,” he said.

Does memory feed on unabolished guilt? Or is it guilt, like a lamprey, that feeds on the memory?

Uncle Munia lived for five more years, almost to 100. And yet, an inveterate believer in telling the truth even if it meant eroding another person’s walls of privacy, Uncle Munia is still more alive than most of my deceased relatives. More charismatic, too.

On the fourth day of his Ladispoli visit Uncle Munia had awoken me at 6 in the morning. “Rise and shine, my boy. I’m taking you all to Pompeii.”

Over breakfast mother said her blood pressure was low and she didn’t have the energy, and I didn’t want to leave her alone. With panic in his eyes, father went to Pompeii with Uncle Munia. The travelers returned by the end of the next day, Uncle Munia bubbling with impressions, father looking exasperated.

Uncle Munia brought us a gift, a book I still have in my home library. I pick it up from the glass bookcase, where it shares a narrow berth with Modigliani, Malevich, and Soutine—and with exhibition catalogs of Uncle Munia’s younger son. I look at the frescos of copulating people and animals and think of the ebullient Uncle Munia and of what my father told me, sotto voce, as we came out to the balcony.

The sun had already sunk into the Tyrrhenian Sea outside our windows. Uncle Munia was in the kitchen identifying to my mother all the amazing things he had seen in the House of the Vestals and the Villa of Mysteries. While Uncle Munia leafed through the book he brought us, showing the “interesting” frescos to my mother, my father described to me how they took the Naples train from Termini and how Gorky, the patron saint of proletarian writers, must have been turning in his grave at the thought of his admirer Uncle Munia crossing almost everything off the bill at an open-air restaurant in Sorrento, the luminous Sorrento where he and my father had stopped for the night before they took a boat to Capri the next morning.

“Capri was something out of this world,” said my father. “And Uncle Munia, Uncle Munia was his own natural self.”

Early versions of sections of this piece appeared in “Waiting for America: A Story of Emigration.”

Maxim D. Shrayer is a bilingual author and a professor at Boston College. He was born in Moscow and emigrated in 1987. His recent books include A Russian Immigrant: Three Novellas and Immigrant Baggage, a memoir. Shrayer’s new collection of poetry, Kinship, will be published in April 2024.