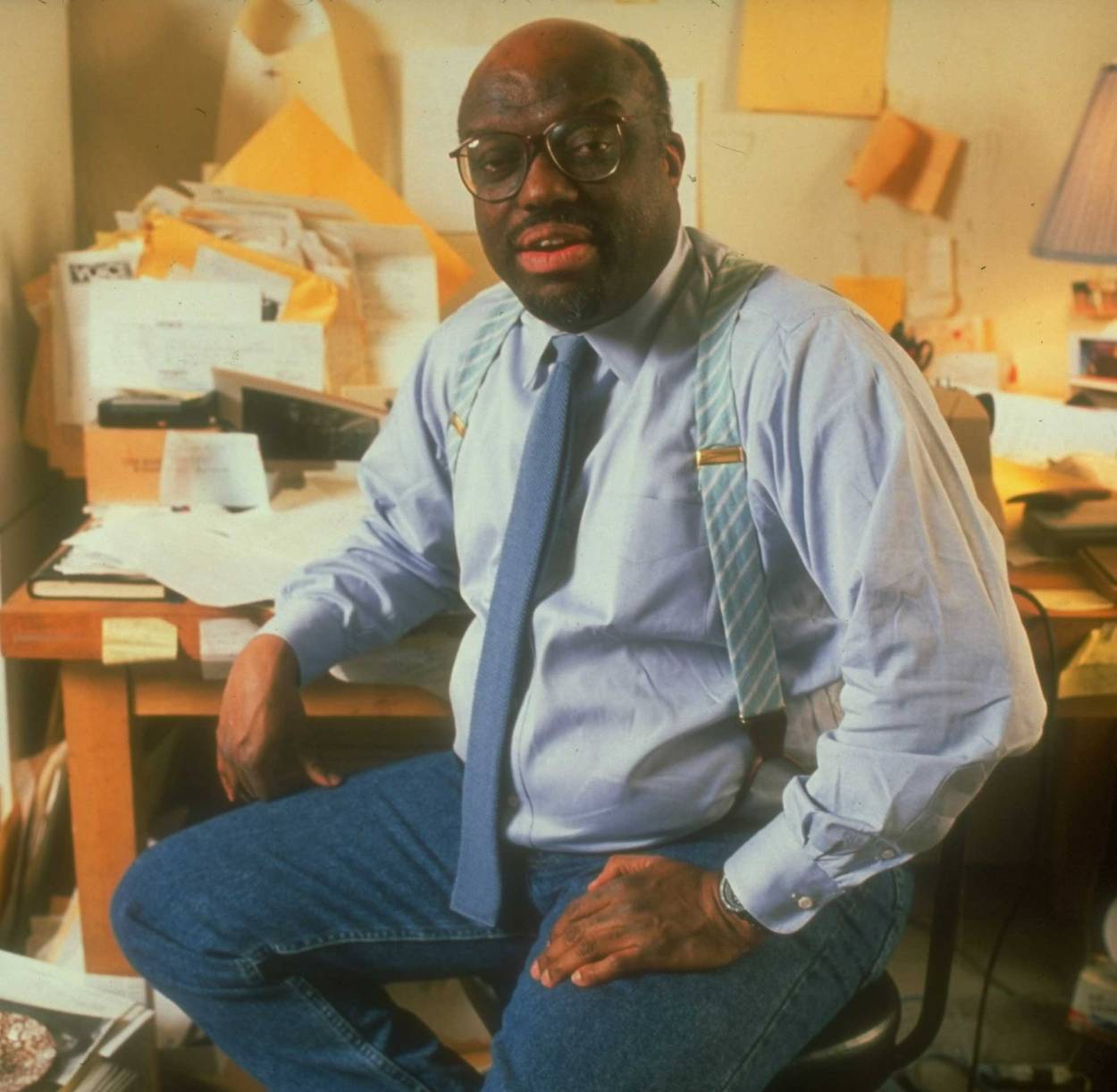

The Great Stanley Crouch

An American immigrant jazz buff expresses his gratitude to a supremely gifted critic who loved the music and loathed bullshit

If I had to name the one writer who was most pivotal for me and for my full assimilation in America, it would undoubtedly be Stanley Crouch, the famed jazz and cultural critic who died last Wednesday in New York at age 74. At this moment in American life, where anything and everything that identifies us and binds us as Americans is under direct assault, Crouch is perhaps more essential than ever, and his passing all the more devastating.

Perhaps even more than Albert Murray and Ralph Ellison, Crouch tied it all together for me. He had a terrific ear for the music I love, and his uncompromising pugnacious style spoke to me directly. For someone who came to America from a sectarian Third World society, his commentary on the Balkanization of America was penetrating and, as we’re seeing today, scarily pertinent.

Crouch had no patience for the self-pitying race politics of grievance and authenticity. He saw it as a hustle and had nothing but contempt for its toxic sales pitch. He arrived at this conviction the hard way, as he explains in the prologue to his fabulous Considering Genius:

The tribal appeal is always great and there is nothing more tempting to the most gullible members of a minority group than suddenly hearing that, merely by being born, one is not innately inferior to the majority but part of an unacknowledged elite. I was not so sophisticated that I could avoid the pull of those ideas and found myself reading all kinds of books about Africa, and African customs and religion. … I would have been pulled all the way into the maw of subthought, from which it might have taken longer to emerge if Jayne Cortez hadn’t introduced me to Ralph Ellison’s Shadow and Act. … Unlike those younger black people who were busy jettisoning their heritage as Americans and Western people—both of which brought the built-in option of criticism—Ellison took the place of his ethnic group and himself as firm parts of American life and a fresh development in Western culture.

This affirmation of Americanness in the face of all tribal impulses, “ethnic narcissism,” and Balkanization, reflects the influence of Ellison and Murray, and their realization, in Crouch’s words, that “America is a land of synthesis.” In The Omni-Americans, Murray builds on Constance Rourke’s description of the composite nature of the American character—“part Yankee, part backwoodsman and Indian, and part Negro.” Blackness, in other words, is a foundational element of the American national character, meaning that all Americans are culturally part Black, whether they like it or not, and that appeals to racial or cultural purity—by anyone, regardless of skin color or claimed ancestry—are sheer nonsense.

Like America, its vernacular aesthetic expression, jazz, is also a composite, an experiment in hybridity. And like America, the Black element in jazz is foundational—not something that needs special pleading or diversity coaches to promote inclusion. Crouch was uncompromising on this point. He fought vigorously against any attempt to remove from its definition the core elements of jazz, which were the contribution of Black artists—blues and swing. As Crouch explained in a superb 2002 essay, “The Negro Aesthetic of Jazz”:

Jazz has always been a hybrid. A mix of African, European, Caribbean and Afro-Hispanic elements. But the distinct results of that mix, which distinguished jazz as one of the new arts of the 20th century, are now under assault by those who would love to make jazz no more than an “improvised music” free of definition. They would like to remove those elements that are essential to jazz and that came from the Negro. Troublesome person, that Negro.

Through the creation of blues and swing, the Negro discovered two invaluable things. In the blues it was framing a melodic line within a form of three chords that added a new feeling to Western music and inspired endless variations. In swing it was a unique way of phrasing that provided an equally singular pulsation. These two innovations were neither African nor European nor Asian nor Australian nor Latin or South American; they were Negro American.

To take the Black element out of jazz is to strip it of its Americanness. Similarly, to see jazz as “universal” music is therefore to deny what makes it jazz. Crouch drives that point home in the essay:

The most recent version of the movement to neutralize the Negro aesthetic was made clear to me by a European 25 years ago. He told me that someday we would all embrace the idea of a great jazz drummer like Ed Blackwell improvising with Asian Indians, North Africans, South Americans, Europeans and so on, each playing in the language of his culture on instruments from his homeland. “This, to me, is the jazz of the future,” he said.

It sounded like the United Nations in an instrumental session to me.

And so, for Crouch, jazz was not simply “improvised music.” It is vernacular art, which like all art is born in a specific place and created by specific people—not by the U.N. It had to include certain “core aesthetic elements,” namely “4/4 swing, blues, the romantic to meditative ballad and Afro-Hispanic rhythm,” or what Jelly Roll Morton called “the Spanish tinge.” Of course, anyone can play jazz, Crouch wrote, “but understand that blues and that swing are there for you too—if you want to play jazz.”

Crouch caught a lot of flak for this view, which critics saw as too rigid and reductive. But, at least when it comes to swing, Crouch has jazz giants, like tenor saxophonist Johnny Griffin, on his side. Griffin described it as follows:

This to me is jazz. Of course, swing; the basis of the whole thing. It’s like Duke Ellington says, I believe if there’s no swing, there’s no jazz. It don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing. I mean, you can say improvisational music, and you can go into all kinds of forms, but I don’t think they should really call it jazz unless it swings. Unless that pulse is there.

That pulse, to quote Griffin further, is “a feeling of how you walk, how you talk, how you approach other people.”

The great drummer Billy Hart elaborated on the meaning of swing in a recent Zoom presentation (yes, one of those), where he clarified that swing is not merely an isometric exercise. Rather, he said, swing “is a philosophy that causes joy and optimism.” That’s the flip side of Murray’s understanding of the blues: “It’s not self-pity music.”

Swing is fundamental to the American character. It is the opposite of self-pity, which is the essence of the resentment of identity and grievance politics, which form the core of the Third World sensibility—the same sensibility that undergirds the toxic anti-American garbage of The New York Times’ 1619 Project. Swing is the contribution of Black Americans, and an affirmation of their foundational place in the shaping of America’s sound and rhythm, its feel and strut.

Jazz, Albert Murray once told an interviewer, is a “metaphor for the truth of the American experience.” As a perpetually forward-looking nation, the American experiment perennially needs to fend off chaos and entropy. Because, too often, what is touted as “progress” is merely cover for toxic hucksterism.

What is scary about the present American moment is that what is being widely marketed as a revisiting or reinterpretation of our story in a time of great social stress is in fact a year-zero, systematic erasure of the past and the ties that bind Americans together. Once the grievance-driven sectarianism that Stanley Crouch and his intellectual forefathers Albert Murray and Ralph Ellison rightly loathed becomes the norm, it entrenches mutual suspicion and vilification, perpetual conflict, separation, and the severing of ties. After all, how can Americans of various backgrounds share anything in common when America is gleefully shattered into pieces, and the concept of assimilating into a common culture is refigured as an act of violent racism?

How can Americans of various backgrounds share anything in common when America is gleefully shattered into pieces, and the concept of assimilating into a common culture is refigured as an act of violent racism?

Inasmuch as jazz is a metaphor for America, it too must contend with the dialectic of structure and chaos, navigating improvisation while maintaining its swing. One of my favorite scenes with a jazz elder (may he live to 120), the wonderful Barry Harris, whom pianist Emmet Cohen—himself a fine example of the joy of swing—lovingly and appropriately refers to as our guiding light, is from a 1985 documentary. Harris, having listened to a band play at his Jazz Cultural Theater, comes up to the stage and goes off on an impassioned riff, giving the band and the audience a piece of his mind on jazz and tradition: “if you’re gonna call this music, I’m gonna insist that it’s not jazz. It’s gonna be jazz according to tradition.”

Reinterpretation—dialogue with tradition—is different from the embrace of chaos. “We want a bulwark against entropy,” as Murray put it.

In that regard, Crouch was tough on John Coltrane’s late period. Most interesting is Crouch’s speculation about what, to his mind, led Coltrane astray:

What Coltrane’s late music does prove, however, is that he might well have been caught up in the ‘hysteria of the times,’ as Cecil Taylor once wrote of him. During that period of the 1960s, everything traditional was under fire, from politics to ethnic identity, for both rational and irrational reasons. It is not impossible to believe that Coltrane was attracted to the romantic fantasies about Africa that black nationalists attempted to impose on both Negroes at large and Negro artists. This was when Negroes sought what should now be recognized as a laughable version of “authenticity” that never assessed jazz itself with any actual depth.

In fact, much black nationalism was really about enormous self-hatred and contempt for Negro-American culture. Its vision misled certain black people into denying the depth of the indelibly rich domestic influences black and white people had had on each other, regardless of all that had been wrought by slavery and segregation. The greatest of John Coltrane’s music reflects that confluence of races and influences.

Using jazz as an explanatory model, Crouch directly addressed the allure of “authenticity” and the search for it in the Third World and ethnic narcissism in his own writing. In “Segregated Fiction Blues,” Crouch wrote how with “the rise of ethnic, female, and sexual preference studies on our college campuses, the idea of being an American writer shrank when it should have expanded.” “From academe,” Crouch went on, illustrating what has become our present-day American sectarian reality, “ethnic groups … talked of ‘their’ history and ‘their’ people as cultural possessions that shouldn’t be tampered with by others for fear of distortion. So-called minorities should be the only ones to handle that material, to assess it, to let everybody know what it means. Whites, forever ready to justify their wrongdoing and praise themselves, couldn’t be trusted.”

Passages such as this one resonated with me, as I was familiar with the underlying Third World toxicity of the phenomenon it described, and saw it firsthand in my own professional field—which was becoming colonized by what another great American writer, Fouad Ajami, labeled “professional ethnics.” Crouch opened up a different world for me. In addition to teaching me about the creators and performers of jazz music, and how to listen to it—a drummer, he had a keen ear for rhythm and rhythmic innovation and its relationship with harmonic movement—and how to see the rhythm in the prose of American writers. He deepened my love for America and enriched my understanding of it. His uncompromising affirmation of individuality solidified my aversion to the pull of the ethnic hustle, identity politics, and the Third World sensibility.

I am sad that I never got a chance to express my gratitude to Stanley Crouch in person. This clumsy attempt, which cannot come close to doing justice to the man or his work, is all I got. But if you’re still reading this piece, I would like to direct you to a beautiful tribute written by Ethan Iverson, who knew and was friends with Crouch. In addition to being a superb pianist, Iverson is a chronicler of jazz tradition, both in his writing and interviews with the jazz masters, preserving tradition and passing down their stories and observations, as well as in his playing, including his collaboration with the masters—collaborations which have allowed me, in the time before COVID-19, to listen in person, meet and talk to my heroes, and to feel America’s joyful pulse: swing.

Tony Badran is Tablet’s news editor and Levant analyst.