Convert’s Tale

A new study assesses the 12th-century memoir attributed to ‘Herman the former Jew’

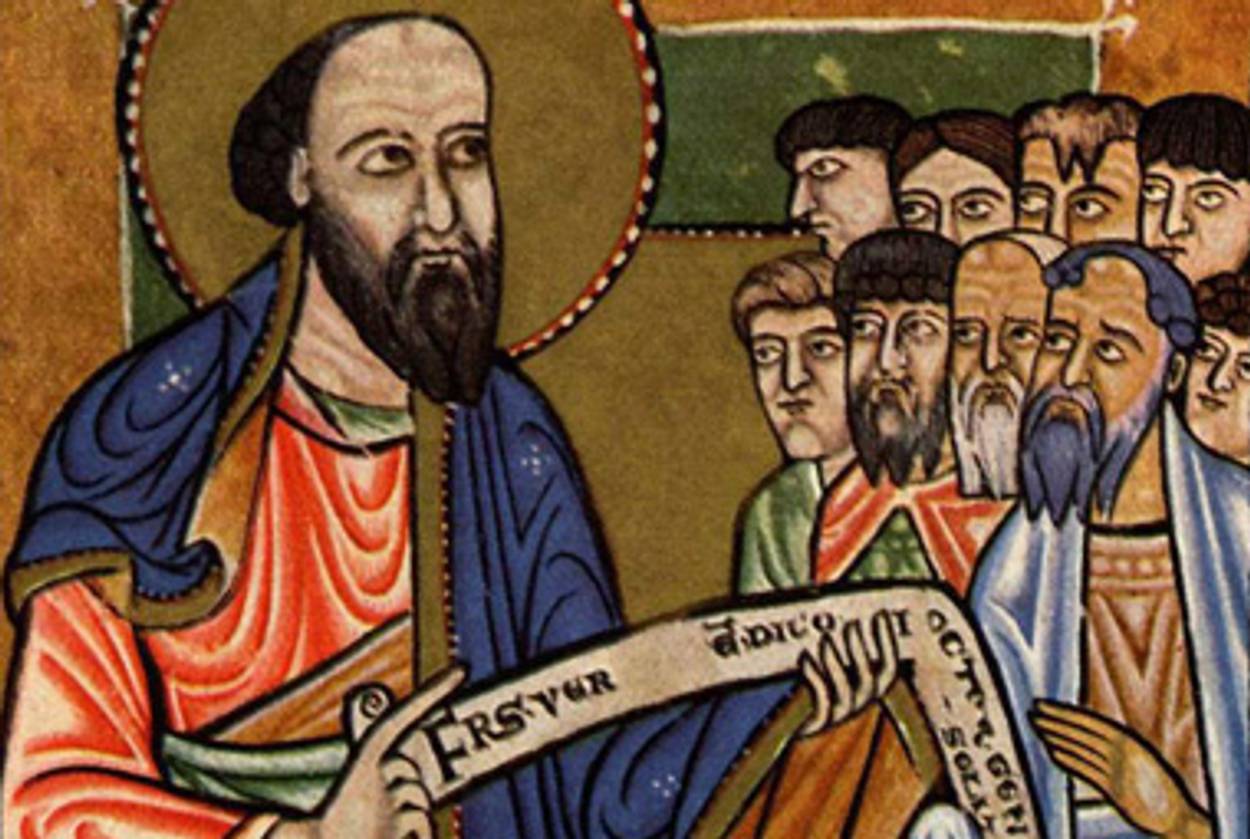

Sometime in the 12th century CE, at the monastery of Cappenberg in western Germany, a fascinating and enigmatic document was produced. Its Latin title, Opusculum de conversione sua, means “A Short Work About his Conversion,” and it is attributed to Hermannus quondam Judaeus—“Herman the former Jew.” What makes this work especially significant, writes Jean-Claude Schmitt in his newly translated study The Conversion of Herman the Jew: Autobiography, History, and Fiction in the Twelfth Century (University of Pennsylvania Press), is that it “is presented in a form that we today call an autobiography.” At a time when autobiographical writing was very rare, a memoir written in Latin by a Jew was unique.

For centuries, the Christian clerics and scholars who read Herman’s book took it at face value, as the confession of a Jew who learned to cast off the darkness and ignorance of Judaism and embrace the truth of Christianity. The Opusculum functioned, in other words, as a textual weapon in the fight against Judaism. Schmitt points out that the first printed edition of the work, in 1687, is included in an anthology of anti-Jewish polemics, whose frontispiece shows a dagger that “reaches out from a celestial cloud and threatens a terrified old rabbi.”

But in the last few decades, Schmitt shows, the Opusculum has become the subject of a new and intense debate. It began in 1988, when Avrom Saltman of Bar Ilan University published an article arguing that no such person as Herman the Jew ever existed. The text was, rather, a “work of fiction, an edifying autobiographical novel,” written by Christians for Christian audiences, in which a genuinely Jewish voice is never heard. This “radical position,” Schmitt sums up, “completely changed the terms of the historiographical debate,” and in the last 20 years medieval historians have argued over whether the Opusculum is fraudulent. If this debate is unusually heated, it is because, as Schmitt puts it, any opinion about the truth or falsehood of Herman’s account rests on “a critical question: could Jews in the past have abandoned the faith of their ancestors consciously and without the usual physical threat?”

The best place to start reading Schmitt’s complex but elegant study is at the end, where the full text of the Opusculum de conversione sua is included as an appendix. (In English, it runs to just under 40 pages.) “Now, then, I, Herman, who was once called Judah, am a sinner and an unworthy priest,” the account begins. “I am of the Israelite people and the tribe of Levi and I was born of David, my father, and Sephora, my mother, in the city of Cologne.” This was the heartland of Ashkenazi Jewry; Rashi lived in the nearby city of Troyes and would have died just a few years before the birth of this Judah ben David Halevi, which scholars date to around 1107 CE.

Ashkenaz was also, at this time, a community in deep crisis. Less than a decade earlier, Crusaders had ravaged the Jewish Rhineland, killing thousands and forcing thousands more to choose between conversion and suicide. This historical background does not enter directly into Herman’s text, but it might, Schmitt argues, inform his discussion of the best way to convert a Jew to Christianity. No one, Herman emphasizes, forced him to convert or threatened him. Rather, he shows a number of pious Christians patiently teaching him, reasoning with him, and praying for him to see the light. He is especially grateful to one Richmar, a kindhearted priest who “acted as a disciple of the true law of the gospel, in which it is said, ‘love your enemies, do good to them that hate you.’ ” Herman implores his readers to follow this example:

For [Richmar] did not curse me as perfidious and unworthy of Christian companionship. Instead, he most devotedly communicated to me works of charity and piety as though I were his fellow Christian. May those stirred with the zeal of piety be horrified at spitting upon the Jewish (or any other human) error, as some customarily do.

This is plausible as the voice of a former Jew, pleading for mercy for his benighted brethren. Yet later in the text, when he has made the decision to convert, we find Judah proudly kidnapping his 7-year-old half-brother, because “I most passionately wished for him to become with me a coinheritor of divine grace through the regenerative cleansing of baptism.” The misery of the boy’s mother, Herman’s stepmother, counts for nothing in comparison: “the excesses of her grief made her mad,” he writes, but though “she ran to the leading men of the city wailing bitterly, and with a sorrowful voice proclaimed that her son had been furtively abducted,” Herman managed to deposit the boy at a monastery. In the 19th century, when a young Italian Jewish boy named Edgardo Mortara was taken from his parents in this fashion, it raised a worldwide outcry; in the 12th century, even a former Jew like Herman saw nothing wrong with it.

But while these episodes seem convincingly lifelike, Schmitt shows that they are also thoroughly symbolic, since the Opusculum is totally structured by the logic of Christian anti-Judaism. Early in the account, for instance, Richmar proposes a bargain to the young Judah: “if, as a trial of his faith, he sensed no burning while carrying a hot iron in his hand (as one normally would), I would faithfully submit to the cure of holy baptism.” Before Richmar can make the experiment, however, his bishop forbids it, since “a sign that is displayed visibly to the external sight would be useless if [God] did not work invisibly through grace in the heart of a human being.”

The scene is carefully designed to drive home the central distinction between Christianity and Judaism, as Christians saw it. Jews only understand the literal and concrete, what is before their eyes—like grasping a piece of hot iron; but Christians understand that the literal is less important than the spiritual, that inward grace is better than outward fact. “This dichotomy,” Schmitt writes, “structures the entire opposition between Jews and Christians” in medieval thought, and it comes up over and over again in Herman’s text.

When Judah first enters a church, he is disgusted by the crucifix, which he considers a “monstrous idol” of the kind that God explicitly prohibited. But when he raises this objection with an abbot, he is taught that the crucifix is not an idol but an aid to piety: “externally we project the image of [Jesus’s] death through the likeness of the cross, internally we are inspired with love for him.” Later on, when his fellow Jews begin to notice Judah’s interest in Christianity, they hope to keep him in the fold by compelling him to get married—that is, by forcing him to lead the life of the body, of sex and procreation. After his conversion, however, Herman becomes a celibate monk, freeing himself from the body in order to live the life of the spirit.

If everything that happens in Herman’s account seems designed to drive home this same, classically anti-Jewish idea, does this mean that the story was invented for this purpose? Or might it mean that Herman has reinterpreted the actual experiences of his life in accordance with the logic of Christian anti-Judaism? For Schmitt, there is finally no way to decide; indeed, the question doesn’t make sense, since the idea of a factually truthful autobiography did not exist in the middle ages. To expect any 12th-century person to “sit down at his desk, alone, in order to write his memoirs,” in the way we might do today, is “totally anachronistic,” he writes. Rather, he argues that the Opusculum should be read as the collective work of a group of monks, writing for other monks, in order to communicate and reinforce their ideas of what Christianity is. Judaism, in Herman’s text as in so many Christian writings before and since, serves this purpose by being made to represent everything Christianity is not. In this way, The Conversion of Herman the Jew illustrates an age-old problem that still has not entirely disappeared: the difficulty of allowing Judaism to speak for itself in a Christian culture.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.