The Cross and the Tallit

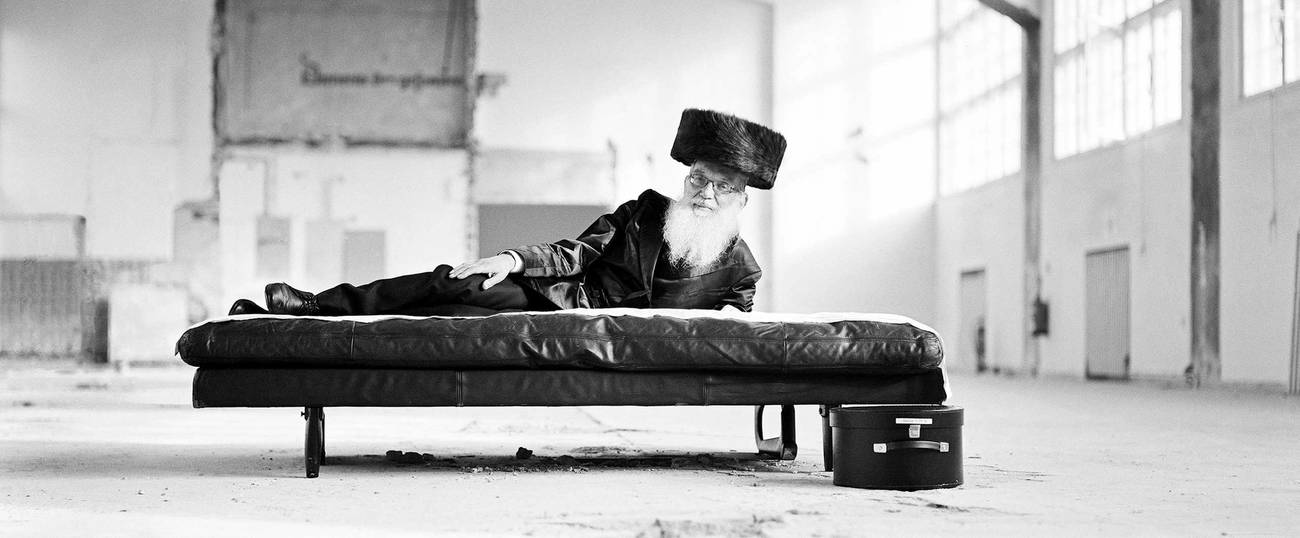

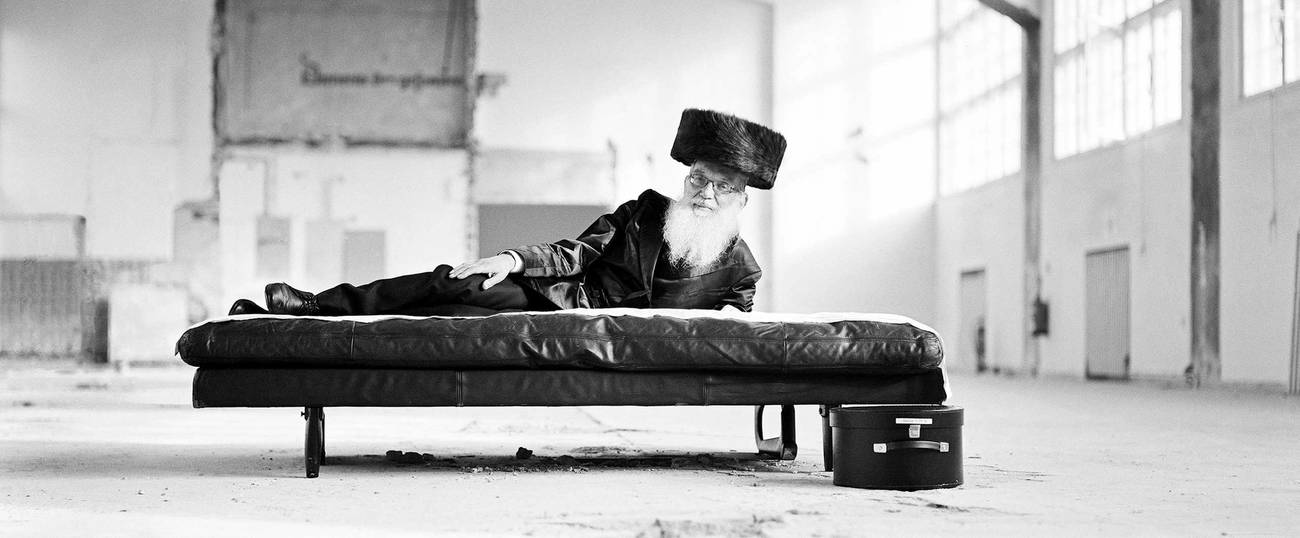

Israeli photographer Benyamin Reich channels his ultra-Orthodox upbringing into haunting images of faith and transgression

In late April 1945 American Air Force planes strafed a train carrying over a thousand Jewish prisoners in the tiny Bavarian station of Schwabhausen. It was the beginning of an extraordinary story that is being commemorated by exhibitions in both a local monastery and in Munich.

Pictures by Israeli photographer Benyamin Reich tell the story of the hundreds of Jewish slave laborers who were being moved from the Kaufering subcamp of Dachau as U.S. forces entered Germany.

Reich’s work explores the dichotomy between his ultra-Orthodox Israeli hometown of Bnei Brak and his open artistic gay life in Berlin, discovering he says, “the contradictions, humanity and erotic tension in my community and myself.”

As a result the Jewish Museum in Munich felt he was the perfect artist to capture the dynamics of Jewish and Christian religious life that collided in the spring of 1945 at the monastery of St. Ottilien not far from Schwabhausen.

The survivors of the attack on the train found sanctuary in the Benedictine monastery where they established a Jewish hospital. As they recovered, their community underwent a Zionist renaissance in the most unlikely surroundings.

To capture the images for a recent exhibition in St. Ottilien and the Jewish Museum in Munich, 41 year-old Reich moved into the monastery. Watching the monks at prayer he found the experience similar to the time he spent in yeshiva.

He began hunting in the attics and disused buildings of the vast complex, where he found an old hospital bed and a tattered blanket on which he placed a handmade Star of David similar to the ones Jews were forced to wear by the Nazis.

By accident he met Father Marinus who was cleaning up the former maternity home where over 400 babies were born to Jewish Holocaust survivors in the years after the war.

“He knew a lot about Judaism and was curious. He could read Hebrew and was the perfect person to hold the St. Ottilien Talmud that was printed in the monastery by the survivors.” The result is an arresting image. It takes a moment to realize that the monk holds in his hand the Jewish holy text.

Reich recalled: “It was Hanukkah and I lit candles on the windowsill looking out over the cloister, as the survivors would have done, hearing the church bells as they blessed the candles.”

‘I think I was always ashamed of my religion, which is closed and afraid of aesthetics.’

Reich pictured a cart in the monastery’s farmyard similar to the one that appeared on the cover of the St. Ottilien Talmud. “Placing the cross and the tallit on it was like closing the gap between the two religions,” he said.

“The world I was brought up in is literally black and white. Men wear white shirts on top and black pants on the bottom.” The starkness of that world attracted Reich “to Catholicism because of the beauty of its churches—the singing and the art. I think I was always ashamed of my religion, which is closed and afraid of aesthetics.”

Reich’s father is an ultra-Orthodox Manchester-born rabbi but his family refuses to fit into the black-and-white conception of Orthodoxy and those who reject it. Reich’s father is, he said, “my best model.” Although his community is ultra-Orthodox, Reich said his father is very open-minded. “He rebelled against his own parents to become more religious but his soul is humanist.”

“One of my pictures of a half-naked boy with teffilin was chosen for an exhibition in a church in Hamburg but was almost pulled as the curator felt it would offend the Jewish community,” he said. “But my father wrote a letter in its defense.”

Challenging perceptions drives Reich forward. He points to the picture he took of his sister and himself posing as Adam and Eve. “It breaks the classic universality of the tale as it looks romantic holding hands in nature but I am gay and she is queer and here we are free in nature.”

Being part of and set apart from the people of Bnei Brak gives Reich a unique insight. “When I go into the community with my camera I can break down some of these walls.” His own emotions sit in the gray zone. “I have an admiration for them as they hold on to tradition, which is romantic, but I feel pity as they do not consider there is another world outside.”

He continued: “I took a picture of a newly married couple. I asked to photograph them on the same bed and for her to put her hand on his. They were very young and it seemed right at the time even though I wondered if I had the right to push them to do this. They are proud and show no conflict but we see they are enclosed in their tradition, above them is the window, dark at night like a prison, and we see in the picture something that will break.”

Rosie Whitehouse is the author of The People on the Beach: Escaping Europe After the Holocaust, which will be published by Hurst in September 2020.

Rosie Whitehouse is the author of The People on the Beach: Journeys to Freedom After the Holocaust.