Two Becomes One

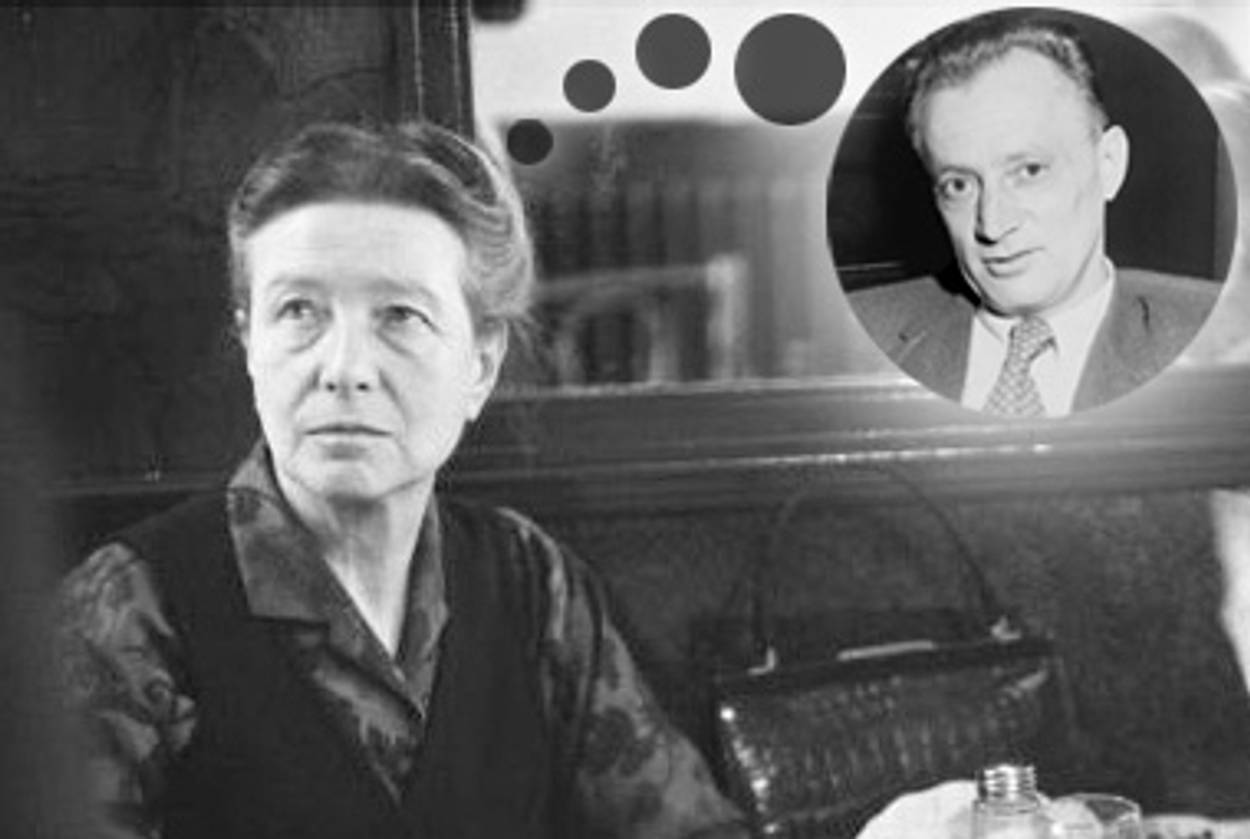

It is no accident that Simone de Beauvoir wrote The Second Sex while having an affair with Jewish novelist Nelson Algren

After Simone de Beauvoir’s father confronted his daughter and her boyfriend Jean-Paul Sartre about their more or less open cohabitation, Sartre proposed marriage, and Beauvoir haughtily told him not to be silly. Judith Thurman, in her introduction to the new translation of The Second Sex, attributes Beauvoir’s refusal to her flouting of bourgeois mores. I submit that something rather less heroic was behind Beauvoir’s rebuff. First, there is the matter of feminine vanity. Intellectual companionship is one thing, but for the turban-and-pearls Beauvoir, calling herself wife to the five-foot-tall, wall-eyed existentialist may have proved insupportable. Second, she intuited early on in the relationship that Sartre “did not have the vocation for monogamy,” that he would never truly, solely, be hers. Their relationship lasted half a century, and he never was.

But the skeleton key may be an affair that Beauvoir had with the scabrous, hardscrabble Nelson Algren, a Jewish novelist of the Chicago school. Beauvoir called herself Algren’s “wife,” a word she never used with Sartre; he gave her a ring. She signed one typical letter: “Good night, my beloved one, my friend, husband and lover. We were so happy, we shall be so happy. I love you so much, my local youth, my crocodile, my own, Nelson.” (In their private language of pet names, Beauvoir was the French frog to Algren’s toothy, toothsome crocodile.) This isn’t the voice we expect from the strong-willed, brilliant feminist, ninth woman ever to pass France’s grueling postgraduate agrégation (in 1929, the top result was Sartre’s, the second Beauvoir’s). But the compulsively prolific Beauvoir wrote over 300 letters to Algren in this tone.

The two met in Chicago in 1946 when Beauvoir was on a lecture tour of the United States with Sartre (The New Yorker gushed about France’s “No. 2 Existentialist”—Sartre being No. 1). Algren recounts:

The phone rang … a heavily accented French voice was saying that her name was, ah, ah, something. I didn’t quite catch it. I said, “Where are you at, I’ll come down.” “Leetle Café,” she told me, in “Palmer House.” … When I got down there all I saw was ‘Le Petite Café [sic].’ She wasn’t taking any chances on my understanding French it looked like.

Algren showed Beauvoir what he imagined to be the sights: “the electric chair, the psychiatric wards … cheap burlesques, a police line-up.” Beauvoir, an unreliable autobiographer but a remarkably candid interview subject, told her biographer Deirdre Bair that she had her first orgasm with Algren at the age of 39.

Being apart was difficult. He coped by gambling, she by drinking. They arranged to meet again, whenever they could; they traveled through Latin America and the Southwest together. Beauvoir’s Catholic family’s attitude toward Jews was less than charitable. She wrote of her parents that “My father was as convinced of the guilt of Dreyfus as my mother was of the existence of God” (that is, completely). But while there is anti-Christian polemic in The Second Sex (she makes much of the Church fathers voting against the indignity of having a God born of woman), her treatment of Jews is slight but fair.

More than Algren’s Jewishness, it is his machismo that startles. A bit of cognitive dissonance sets in when one learns that The Second Sex was written while Beauvoir was romantically involved with a man whose calling card was his working-class virility, his easy assumptions of male superiority. But it was Algren to whom Beauvoir broached the idea of writing on women, and it was Algren who encouraged her to expand her essays on women into a book. The year 1949 saw the publication of both The Second Sex and Algren’smost famous novel, The Man With the Golden Arm, which was made into a movie starring Frank Sinatra and Kim Novak.

The feminist tradition since Wollstonecraft has been led by women to whom men acted less than reliably. Beauvoir is no exception. Her grandfather bankrupted the family, her father didn’t trouble himself to find work, and Paul Johnson’s characterization of the formidable Beauvoir as “Sartre’s slave” is not inapt. Beauvoir cooked, cleaned, and sewed for Sartre. She looked after his money and edited his work; sometimes she wrote it. Before his reputation was established, the yellow-toothed writer had trouble attracting women and turned to Beauvoir to procure lycée students for his Saint-Germain-des-Prés seraglio (an arrangement that led to her teaching license being revoked under charges of abducting a minor).

But Algren, whatever tough-guy image he cultivated, was a loyal and estimable man, and he seems to have held out hope, at least for a while, that Beauvoir would leave Sartre to be with him in Chicago. Though his correspondence to her remains unpublished, we can guess from Beauvoir’s responses that it was solicitous, loving, and boastfully risqué. By that point—though Beauvoir had been with the domineering Sartre for 17 years and French women had gained the vote only two years earlier—she still claimed that she had no sense of inequality between the sexes and perceived it only as she began her research. The New Yorker’s Joan Acocella surmises that “the crucial research took place in Nelson Algren’s bed.”

Algren’s Jewish background is itself interesting. He describes his mother’s family as “West Side [Chicago] German Jews who knocked themselves out to repudiate their Judaism immediately.” His paternal grandfather and namesake was a Swede named Nels Ahlgren who came to America at the age of 18, just before the Civil War, having plucked out of thin air the idea that he was Jewish. He changed his name to Isaac Ben Abraham and adopted an idiosyncratic, literal-minded faith that appears to have been sincere and that lasted for decades.

Algren’s grandfather’s Zionist fervor prompted him to move the family to San Francisco, where in two or three years he saved enough money to move the family to Israel. In Israel he made a thorough nuisance of himself, being more knowledgeable than the scholars and holier than the rabbis, and left the business of earning money to his wife. Eventually his wife had enough and arranged for the family to return to America. But the money that the American Consulate gave her had pictures of presidents on it. If man is made in the image of God, reasoned Isaac Ben Abraham, and we are forbidden from making graven images of God, then by the transitive property, there are forbidden graven images of God on the bills. He flung the passage money overboard, pauperizing his family.

Beauvoir wrote voluminously about her relationship with Algren, both nonfiction (America Day by Day) and barely disguised fiction (The Mandarins, the novel which won her the Prix Goncourt, has a character based on Algren and is dedicated to his real-life inspiration). After five years, the Beauvoir-Algren relationship, mostly conducted through the mail, began to fray. He subjected her to his dark moods and his jealousies; she wrote a strange and possibly not unrelated defense of the Marquis de Sade. She had exploded on the international scene; his literary reputation seemed to be waning. By the time the third volume of her autobiography was published, with a full description of the affair, Algren’s feelings had soured and he was enraged. “She’s fantasizing a relationship in the manner of a middle-aged spinster,” he said. “Will she ever quit talking?”

However foundational The Second Sex is, Beauvoir’s reputation is far from secure. These days she is routinely called “masculinist” and sexist. When her Letters to Sartre came out, with its revelations about Beauvoir’s luring philosophy students to the lecherous Sartre, she was called a pimp and a lesbian (Beauvoir sometimes participated in the sessions). Further, the book has not aged well: Existentialism is extinct as a school of philosophy, and modern women find Freudian descriptions of the terror struck in the hearts of menstruating girls trite and untrue. The imperious thesis—”On ne naît pas femme, on le devient;” “One is not born a woman, one becomes one”—parallels the first line of Rousseau’s Social Contract;today it has been raised as a banner of transgenderism by Judith Butler and other feminist scholars. I would love to know if Beauvoir would see this as distortion or logical extension.

What is almost guaranteed is that if Beauvoir lived today, in the wake of The Second Sex, her personal life would be very different. In 2005, Kurt Vonnegut described in a poem “the world-class novelist Nelson Algren, /onetime lover of Simone de Beauvoir.” Algren surely didn’t expect, however the dust settled, to be referenced in an ancillary way to his “Frog wife,” but then Beauvoir probably would have had mixed feelings about being remembered as “Sartre’s girlfriend.” Beauvoir survived Sartre by six years; she had her final say in Adieux: A Farewell to Sartre,in which she laid bare the details of Sartre’s debilitated last decade: his drool, his drunkenness, his incontinence, his loss of mind (revelations about his ineptitude as a lover came later). Sartre had secretly adopted his Algerian Jewish mistress, Arlette Elkaïm, as a daughter and bequeathed everything to her: his money, his property, and control of his literary estate. In this, Sartre was effectively spitting in the face of Beauvoir’s decades of devotion. One is not born self-refuted and disgraced, one becomes so. But whatever she tolerated from Sartre, she never forgot Algren, “the only truly passionate love in my life,” and she never took off the silver ring he had given her. In the joint grave in Montparnasse Cemetery (the first name on the headstone is Sartre’s, the second, Beauvoir’s), she is buried in it.

Margot Lurie is associate editor of Jewish Ideas Daily. She last wrote for Tabletabout her grandfather, Yeshiva University’s first Sephardic student.

Margot Lurie is associate editor of Jewish Ideas Daily. She last wrote for Tablet about her grandfather, Yeshiva University’s first Sephardic student.