Yakov Smirnoff Brings Reagan-Era Optimism to the Age of Trump

Investigation reveals the hardest working post-Soviet comic has clear ties to Russia and direct connection to a president. America, what a country.

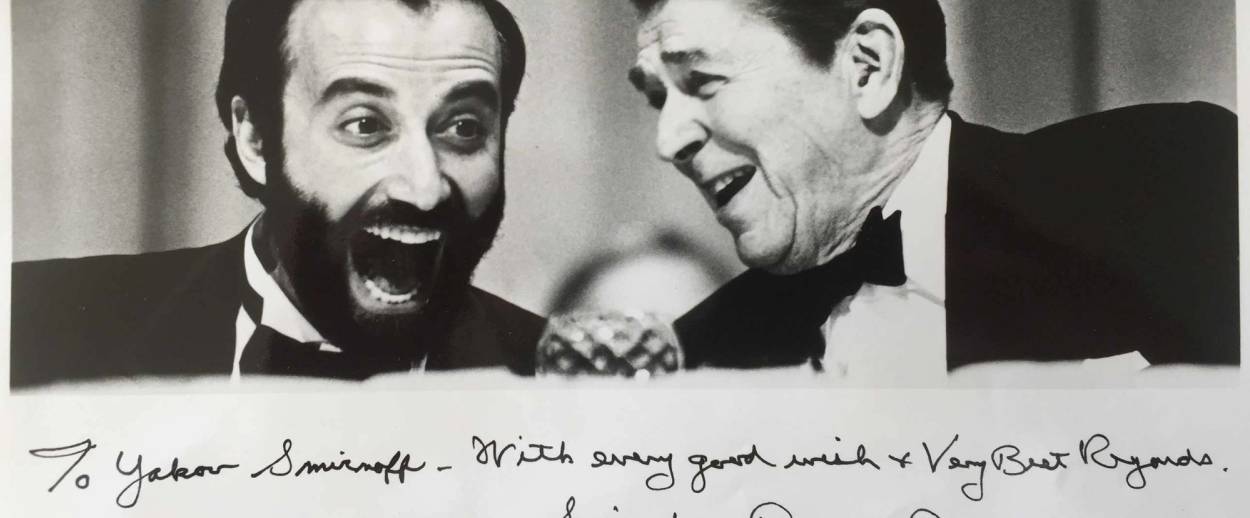

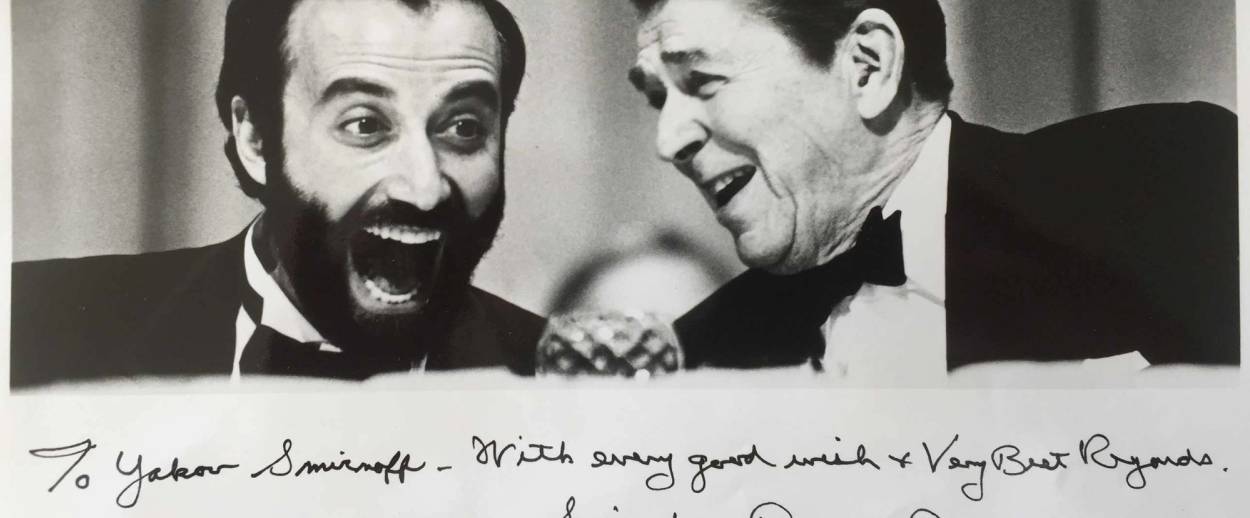

In the span of a decade, Yakov Smirnoff went from entertaining tourists on an Odessa cruise ship to dining with President Ronald Reagan. He became, as former Reagan speechwriter and now Congressman Dana Rohrabacher told me on the phone, “one of the inner circle” of advisers who offered insight, context, and punch lines for the president’s speechwriting team, putting words in the mouth of “The Great Communicator.” “He was giving us information and material that was very well-done, valuable, and poignant—things that we could actually use.” A few years later, Yakov Smirnoff was often a punchline himself. Now, the Russian comedian is mounting what may be a timely comeback.

On a recent drive due north on the Van Wyck Expressway into Manhattan from JFK airport, Smirnoff was sitting in the passenger seat, looking svelte, tanned, well-groomed, and oddly color-coordinated, with his lime-green button-down shirt, lime-green cellphone case, and a lime-green luggage set, which he had just tossed in the trunk. The conversation was moving much faster than we were; it took us nearly three hours to get to Smirnoff’s hotel in Times Square, for a gig at Gotham Comedy Club at 7.

We had been in the car for less than an hour and we had already arrived at Smirnoff’s theory on why marriages fail. His new tour and accompanying PBS Special, Happily Ever Laughter: The Neuroscience of Romantic Relationships, is a venture in what he terms “transformational comedy.” In other words, it’s not comedy that’s meant to poke fun at Donald Trump or make observations about the incongruities and ironical truths of our lives. It’s motivational speaking or self-help with a patina of stand-up: Yakov Smirnoff wants to save your marriage, for it is too late to save his own.

***

If you’re above the age of 30, you’ll remember Yakov Smirnoff as a young, thickly accented Jewish Russian immigrant back when the Soviet Union was still America’s greatest enemy (or is that still true?). His catchphrase—“What a country!”—was, I now realize, not inorganic. On stage, the comedian had perfected a naïve yet ironic self-portrait of a Russian immigrant so inured to a nanny state that upon (mis)reading a furniture advertisement in an American newspaper that declared, “We stand behind our furniture,” he wondered why he had bothered leaving Odessa; he could have had people hiding behind his furniture there, too. But in his eyes and his famous guffaw, one could also detect a real child’s joy at being in the land of the free. In person, even 30 years later, Smirnoff is still genuinely in love with this country.

To be fair, if you came here speaking no English and a decade later were on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show and having dinner with Ronald Reagan, you too would be thinking, “What a country!” When I spoke with Galina, Smirnoff’s childhood friend, at the club bar after the show—which featured Smirnoff for a few minutes, bookending the show and introducing each comic— she told me that her and Smirnoff’s families lived in the same communal apartment in Odessa. Her family lived in one room, Yakov and his parents lived in another, and they shared a bathroom and a kitchen, along with seven other families. Galina came to the United States first and was there to welcome Smirnoff’s family when they arrived in 1977. Smirnoff was sitting across from me at the table in a neon blue shirt, a black tie with glitter sprinkled across the blade, and an Armani belt buckle. He merely smiled when Galina described the incredible insolence of the young refugee.

“He came off the plane, he’s telling me, ‘I’m going to be a comedian.’ Could you imagine?” she told me, mixing Russian and English together in a bilingual mishmash. “I cried. His mother cried. Hysterics. I said to him, ‘What are you gonna do? Your parents are going to starve!’ ” His father and mother—an inventor manqué and a teacher of Russian literature—didn’t starve, however, because Smirnoff found work at Grossinger’s Hotel in the Catskills. As a bar-back, he watched how other comics performed, worked on his English, and judged the quality of the jokes he told by the size of the tips. When the season was over, he went to California to pursue his Hollywood dream.

Mitzi Shore, the owner of the legendary Comedy Store in Los Angeles, let him take the stage once for amateur night. After his few minutes, she gave Smirnoff encouragement. “There’s always room for good and different,” she told him. He should come back. And because she owned a house next door to the club that she rented to comics, she added, “If you want it, you can have one of the rooms.” She told Smirnoff to bring his parents West, gave his father work doing odd jobs around the club, and from there, Smirnoff’s trajectory was rocket-like, and his act still bears the imprint of the decade that made him. He’s a punchline guy, in many ways the wildly successful king of kitsch, and an utterly family-friendly comic. He’s the guy whose jokes will never offend, and while you may roll your eyes at the hygienic puns, he’s clever and funny.

To illustrate this point about just how different Smirnoff is from most comics of his era, he tells a story about the Comedy Store house, called Cresthill. Its roof gave shelter and a sort of spiritual-comedic succor to some of the greatest partiers of the century: Sam Kinison, Robin Williams, Richard Pryor, Andrew Dice Clay. But Smirnoff was never into that. He went to sleep at 11 or 12 each night and would come downstairs in the morning to find a mirror on the table, with powder on it. And he’d think to himself, they’ve been eating jelly doughnuts again. He’d say, “Guys, why don’t you use plates?” It took a few weeks before they finally told Smirnoff that it wasn’t sugar but cocaine.

Smirnoff remembers Rodney Dangerfield in a big bathrobe, together with Kinison, sitting in front of a pile of cocaine 6 inches high. “Come on,” Dangerfield, built like a sedan, cajoled. Smirnoff, who today is well-toned but back then was economy-sized, politely demurred. Amid the blue-comedy revolution of the 1980s, Smirnoff’s was a wholesome and unique voice (literally: he was the only famous stand-up who had a thick Russian accent) that slaked the public’s thirst for knowledge about what went on beyond the Iron Curtain, and simultaneously tickled America’s patriot bone.

And then this happened: One night in the late 1980s, after doing a show at Comedy Café, a comedy club attached to a strip joint, Smirnoff was approached by Arnaud de Borchgrave, who was then editor in chief of the Washington Times. As Smirnoff tells it, de Borchgrave “said that President Reagan is going to be a dinner guest at his house a couple of weeks from now and he thought it would be cool if I wanted to be one of the guests. I thought he was full of it.” Attendees included Jim Baker, “the Ambassador of France, and a few other dignitaries.” When Reagan was introduced to the Odessa comic, he looked at Smirnoff and said, “Well, have you heard this joke?” They exchanged anecdotes all night.

Reagan himself was a natural joke teller; one of the president’s speechwriters reached out to Smirnoff a few months later to ask for help writing material for Reagan’s historic visit to the Soviet Union.

“I was honored but I’m also thinking if this doesn’t work I don’t have any more countries to go to,” Smirnoff told me as we inched closer to the mile-high billboards of Times Square. (You can see some of Smirnoff’s jokes for Reagan here). Smirnoff tells me he is responsible, at the very least, for the one about shooting the curfew breaker and a speeding Gorbachev.

***

“First of all, everybody loved him,” remembers Rep. Rohrabacher, who claims to have written more speeches for the president than anybody else over his seven-year tenure. When he left the White House to run for an open House seat in Southern California, Rohrabacher called on an old friend to do a desperately needed fundraiser: Yakov Smirnoff “raised a lot of money” for the budding lawmaker’s campaign. And then, almost as quickly as the Soviet Union collapsed, so did Smirnoff’s career. He went from being relevant to a relic. Big-city gigs dried up; TV contracts weren’t renewed; Letterman, Yakov claims, poked fun at him in a top-10 list (though I couldn’t confirm this); and Ben Stiller cruelly mocked him on his short-lived MTV show, falling to his knees crying, “I am cold, I am frightened, what will the new world order bring for Yakov?”

But if Smirnoff is anything, he’s resilient: This is a guy who learned English well enough at 26 to become a famous Russian comedian in America. A few people mentioned a place called Branson, Missouri, and 60 Minutes had just aired a spot about the city in the Ozarks which, the program claimed, “may be, person for person, the richest town in the country.” So, desperate for work, Smirnoff and his then-wife, Linda Dreeszen, moved from Los Angeles to the middle of the country, eventually opening their own theater, where he performed up to 400 times a year. Late-night TV might have had enough of Smirnoff, but the faithful visitors to Branson, Missouri, the mecca of clean fun, couldn’t get enough of him. His website claims he performed for 4 million people over 23 years.

In a way, Branson was the perfect place for Smirnoff—the Christian version of the Catskills, with patriotic country-and-western and gospel concerts, the Creation Experience Museum, and the Sight and Sound Theater, which has played host to musicals based on the lives of biblical figures Jonah and Noah. Smirnoff’s show, in one iteration, was called I Bet You Never Looked at It That Way, and it consisted of jokes, storytelling, and Russian folk dancers. At one point, dressed in full rhinestone-cowboy regalia, he rode a horse called Boris onto the stage and sang a twangy tune, then trotted onto the wings after making a crack about needing more horsepower. When he came back on, he was driving a red Ferrari. “Thank you very much, ladies and gentleman,” he would say. “When you have your own theater you can pretty much park anywhere you want to.” This was (mostly) good, clean fun. And it played very, very well in Middle America.

But Branson also brought with it personal challenges. Smirnoff’s marriage fell apart. By that time, he had two small children. He and his wife weren’t laughing together anymore, they weren’t having fun in their relationship. The divorce hit him hard. “There was no drinking, no drugs, nothing obvious that made us go, ‘Well, of course, look at that.’ It was just slow separation.” In his new show, Smirnoff talks about a moment that propelled him onto his quest for the holy grail of relationships, which he believes boils down to being able to answer this to satisfaction: “Why didn’t you and Mommy live happily ever after?” That’s what his 7-year-old daughter asked him one night after he read her a fairy tale. As he tells me the story, his voice quavers with the typical Smirnoffian mix of pathos and humor. “I came up with a great answer,” he says. “I said, ‘Go to sleep.’ ”

Eventually, his quest took him to the University of Pennsylvania, where in 2006 he received a master’s degree in psychology. His thesis adviser was Martin Seligman, one of the fathers of positive psychology, which might otherwise be called the science of self-help. Smirnoff’s theory—which he’s now going to pursue in the doctoral program at Pepperdine University—is that laughter is quantifiable, and if it is quantifiable, then it can be used as a gauge to let us know when our relationships are failing. Think of it like a gas tank, he tells me. If your tank is only a quarter full, you know you’ve got to find a gas station soon or you’ll be stranded on the side of the road.

I emailed Seligman a series of questions about Smirnoff’s work. Seligman is not convinced that laughter can be quantified, though he does believe it’s a good indicator of the health of a relationship. He wrote that Smirnoff “marched to his own drum” and was “one of a kind, original, constructive, funny.”

“Have you done work yourself on laughter as medicine, per se?” I asked him.

“Yes,” he wrote back. “It failed.”

Still, Smirnoff is strongly convinced that laughter can be measured, and to help spread his gospel, he has turned this message into a one-man show. He has a convenient acronym—GIFT (I can’t possibly tell you what the letters stand for)—to describe the steps we need to take to improve our relationships, and he’s joined on stage by a handful of props, including a poster of a smiling Einstein, a screen display of a woman jumping into the arms of a man on a sandy beach, a living-room chair, an old bureau, and several paintings he himself created. Watching it, I can’t make up my mind whether it’s a comedy hour or an infomercial. But, either way, I want to see it till the end.

When I met Smirnoff at the Marriot Marquis in Times Square a few days after his Gotham show, he was dressed down in shorts, a T-shirt, and a NASA baseball cap. We kept moving seats to avoid the sun that seemed to be following us through the massive windows of the 8th-floor atrium. I asked him if he was planning on writing a book about his new comedy project. No, he said, he doesn’t want to do that until he finds a partner who truly understands him, and vice versa. “Our last frontier in this world really ends up with finding a consciously sustainable happy and loving romantic relationship.”

As I got up to leave, he told me something like a religious parable: God wanted to hide happiness in a difficult spot so that humans would have to work hard to achieve it, and thus treasure it. The angels suggest a few places—the top of a mountain, the bottom of the ocean. But God knows that humans will be smart, and it won’t take them long to find it way up high or way down low. After rejecting all the whisperings of the angels, God has his or her eureka moment: “I’m going to hide it inside of them. It’ll take them forever.”

“Which I think is where it is,” the Russian comedian concluded.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Ross Ufberg is a writer, translator, and cofounder of New Vessel Press. He’s a staff writer at BreakGround Magazine covering technology and design.