A.B. Yehoshua Should Pipe Down

The Israeli novelist and liberal icon regularly disparages Diaspora Jews. So, why do Americans still give him an ear, and a platform?

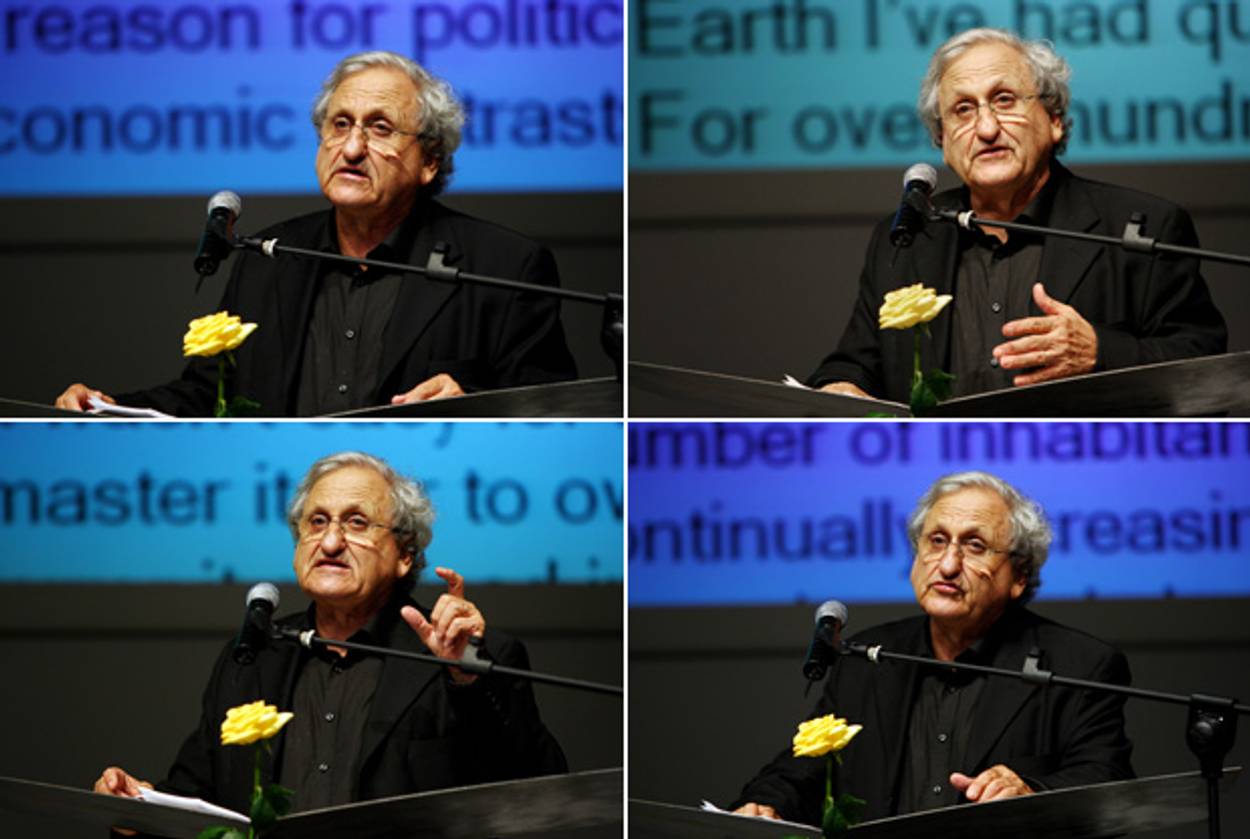

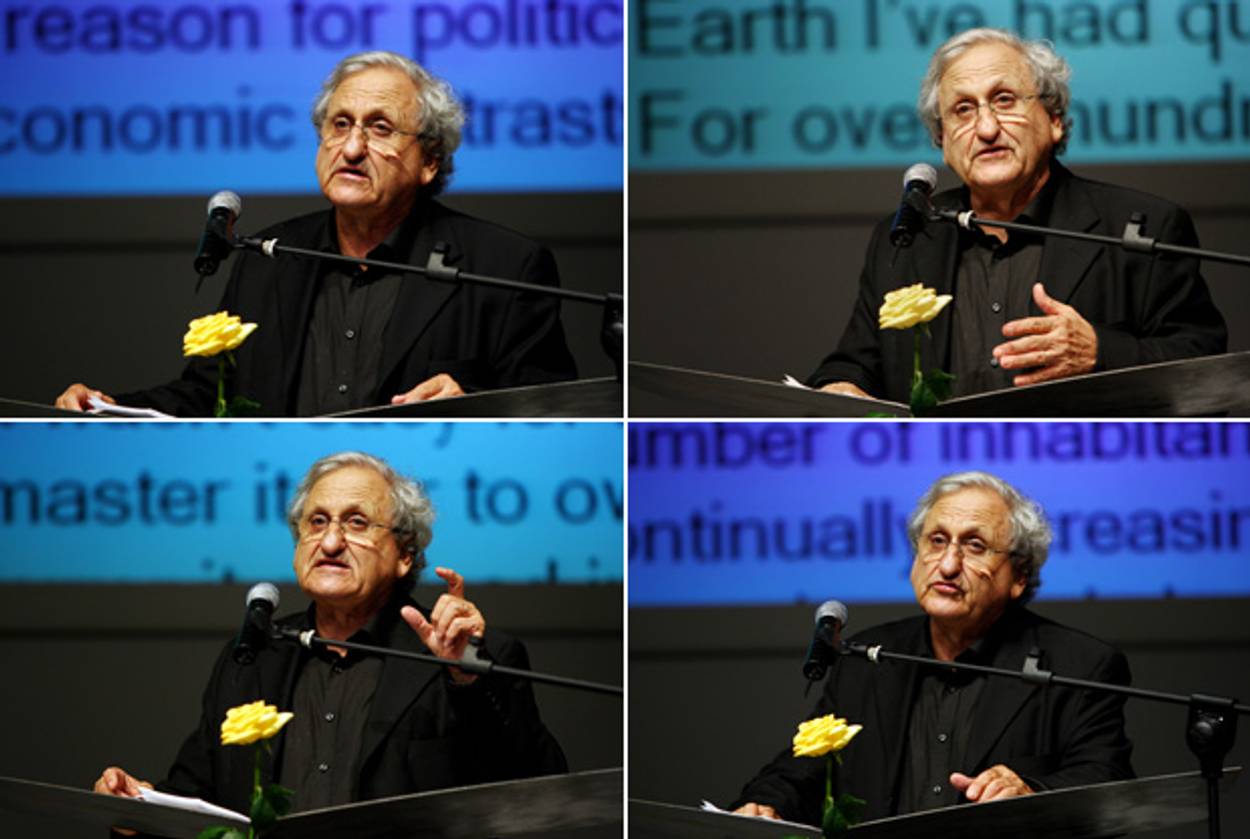

Every few years, the Israeli novelist A. B. Yehoshua writes an outrageous op-ed or delivers the same ideas in a public speech, invariably directed at an English-speaking audience. The message has been the same for quite some time now: Israeli Jews are “complete” Jews, living as they do in an environment defined by pervasive Jewishness—with a Jewish calendar, Hebrew in the public square, and responsibilities for every aspect of building and sustaining a Jewish civilization. Diaspora Jews—especially Americans—are “partial” Jews, living as they do in a pervasively non-Jewish environment and capable of turning off and on their Jewishness in their local institutions and the sites with which they affiliate. Since he is an excellent author, Yehoshua’s better-developed versions of this stump speech come with memorable turns of phrase; in the most famous version, delivered several years back at American Jewish Committee headquarters, Yehoshua located Diaspora Jewish identity in “a fancy spice box that is only opened to release its pleasing fragrance on Shabbat and holidays.” A more frivolous analogy to Jewish practice, and a more demeaning take on a vibrant Diaspora Jewish community, cannot be found.

Never mind the real relevance of the mutterings of an ornery author as he veers unpleasantly into public policy; I am more mystified as to why American Jews continue to give Yehoshua an audience before which to air these grievances. The AJC example is the best one: Yehoshua’s original speech making this audacious claim about the relative merits of Israeli and American Jewry was by invitation at the centennial celebration of the American Jewish Committee itself. Once the flagship institution of American Judaism and the site of a proud assertion of Jewish political strength in the Diaspora, the AJC celebrated its strength by inviting a polemicist to mock them to their faces. Shocked by the content of Yehoshua’s presentation, the AJC then invited Yehoshua back some months later for a symposium built around his remarks, during which time he exacerbated his critique with the above analogy, even going so far as to say that equivocating between American and Israeli Jewry undermined “the moral significance of the historic Jewish grappling with a total reality.” Put differently: Not only is Israeli Judaism fundamentally and even empirically superior; but it is also unethical to even call this hierarchy into question.

And now again last month Yehoshua gave a similar speech to Diaspora Jews and got the requisite write-up, and more Diaspora Jews—or possibly the same ones who were agitated the first time—are up in arms. So, what is this about for A. B. Yehoshua? And why are we still paying attention?

A generous approach to this ideology—that is, one that seeks to understand its foundations irrespective of its pernicious motives and consequences—finds two classical foundations for this idea. The first and most basic is the fundamental premise of biblical Judaism: Jews were meant to live in the land of Israel, their promised destination and the site at which their covenantal dreams would be realized, and the various destructions and dispersals were painful hiccups that never mitigated this original vision. Accordingly, since the opportunity to “return” has reappeared, this vision becomes once again not only an option for Jews but essential and defining. The failure to do so is just that, a failure; Diaspora was always an inferior state to the ideal condition of living in the land of Israel, and voluntary Diasporism is somewhere between folly and criminal.

The more positive or hopeful approach to understanding Yehoshua and making sense of why this ideology still matters focuses less on its foundations in the ancient Jewish past and more on what a Jewish state actually surfaces as possibilities in the present. A Jewish civilization makes certain features of Judaism possible in ways that Diaspora does not—from land-specific biblical commandments, to a calendar that moves out of the realm of the liturgical to something bigger, and to the most ambitious: a Jewish society that requires and is predicated on Jewish values about politics and ethics. The state becomes a testing ground for a set of ideas and theories that otherwise were merely the fodder for study-house debates and dusty volumes. Yehoshua’s lament about the failure of American Jews to immigrate to Israel stems, in part, from his seeing a failed opportunity to animate a Jewish public conversation with as many and as diverse voices as possible.

Of course, both of these conceptual foundations can be critiqued (and are deserving of it). The critique of the first is that it misunderstands the depth of Jewish wanderlust, and the extent to which whenever there has been land there has been diaspora. Zionism is grand, but ain’t no land big enough for the Jewish people to all inhabit at once—a lesson learned many generations earlier by Abraham and Lot upon their arrival into Canaan. The desire for home has been a stronger literary motif for Jews than actually being at home, which—until now—has never been that successful. What’s more, it is only in the messianic age that the return to landedness goes from being an option to being a necessity; and the brokenness in which we currently live suggests that the messiah has yet to arrive. If Yehoshua is relying on a reading of classical Judaism to critique his Diaspora brethren, he is woefully under-read in the full extent of that tradition.

But if Yehoshua’s argument hinges on the second approach—that living in Israel enables certain possibilities for Judaism that are not possible without sovereignty—then he may actually be right. But he is only half right. The same case can be compellingly made for Diaspora. If a Jewish state is a live testing-ground for Jewish possibility in real time and in real conditions, Diaspora has always been the laboratory environment for the creating and testing of Jewish ideas in so-called pristine conditions. It is no wonder that the synagogue is a Diaspora creation, as Jews had to figure out how they could create concentrated community once the public square was no longer theirs to control. Even to the present, though the American Jewish community is far from perfect, there is something achievable in the realm of the private and in the status of minority that enables Jewish possibilities to emerge that entail an actualization of important Jewish ideas.

So, Yehoshua is right about the possibilities for Jewishness that the state of Israel enables, but it is a mystery as to why it must be a quantitative hierarchy: why one has to be better or more complete than the other. Diaspora Zionism should aspirationally mean the ability to see possibilities for Jewishness that emerge from both a sovereign state and a vibrant minority—and further, the ways in which these can be mutually reinforcing. Ask Israelis who spend time in American Jewish communities, and many of the same people who could not breathe in the conditions of public Jewishness in Israel find comfort and warmth in Diasporic Jewish communal frameworks.

The irony is that Yehoshua’s position actually lets Israel and Israelis off the hook. By pinning Jewishness to just being in a particular place, a Jew needs not do anything to sustain this deep level of Jewishness. Yehoshua can only be right to the extent that Israelis commit themselves to building Jewish values into the fabric of the Jewish state, to be engaged in the rigorous work of building aspirational Israel as the embodiment of the best that a sovereign state enables for Judaism. As now over a million Israelis have left this work of state-building behind, and as Israel’s public Jewish face is increasingly characterized by the ugliness of Judaism’s most fundamentalist elements, Yehoshua’s “total Jewishness based on living in Israel” risks becoming thinner and thinner, code for an ethnic veneer.

And this then should put its own pressure on American Jews to apply the same aspirational rigor to our Diaspora contexts. It is interesting: Part of the reason that American Jews continue to listen to A. B. Yehoshua is that he not only plays into the unspoken ideas of many Israelis about the fundamental superiority of their assertive and public Judaism, but also that he plays into what exactly American Jews tend to like about Israel. American Jewish Zionists often embrace exactly these features of public Jewishness: Street signs in Hebrew! Shabbat is a day of the week! Kosher McDonald’s!

What’s worse, the American Jewish community perpetuates Yehoshua’s hierarchy with its educational agenda. The most widely celebrated innovation in Jewish education in decades—Birthright Israel—aims to foster positive Jewish identity by taking American Jewish kids away from their communities and to Israel, the Jewish Disneyland. Not surprisingly, the program fosters positive feelings toward Judaism and the Jewish people, but virtually no change in Jewish affiliations or behaviors.

Some ancient Jews figured this out and saved on the travel budget. Philo of Alexandria was a proud resident of his auspicious ancient homeland and wrote of his dual affiliation to the metropolis—the mother city—of Jerusalem, as well as his ancestral Alexandria. The Judaism that they produced was radically different in both places, with the Temple defining public Jewish culture in one place, and the ancient synagogue creating community differently in another. What we love about our Diaspora homelands cannot be captured in spice-boxes; in contrast to the laziness that Yehoshua’s passive identity ultimately promotes, Diaspora Jewishness requires ongoing and serious commitment to the affirmative expression of minority values in a majority culture, to the willful preservation of difference.

This is why the indignation over the Israeli Ministry of Tourism’s ads targeted at Israelis and encouraging them to return “home” was such a breath of fresh air: It represented the assertion by American Jews and their leadership that living in America was neither a holding-pattern toward inevitable return, nor a depreciated condition; that it was unfair to assume, as some of the ads did, that in addition to the loss of “Israeli-ness,” residence in Palo Alto or Cambridge meant an automatic loss of Jewishness. Would that the Israeli government ended such ads by encouraging Israelis to visit their local JCCs.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Yehuda Kurtzer is president of the Shalom Hartman Institute of North America, a Fellow of the iEngage Project, and the author of Shuva: The Future of the Jewish Past.

Yehuda Kurtzer is President of the Shalom Hartman Institute of North America and host of the Identity/Crisis Podcast.