The Yiddish Journalists of Argentina

A newly translated book spotlights the country’s long-forgotten Jewish journalism, and the immigrants who shaped it

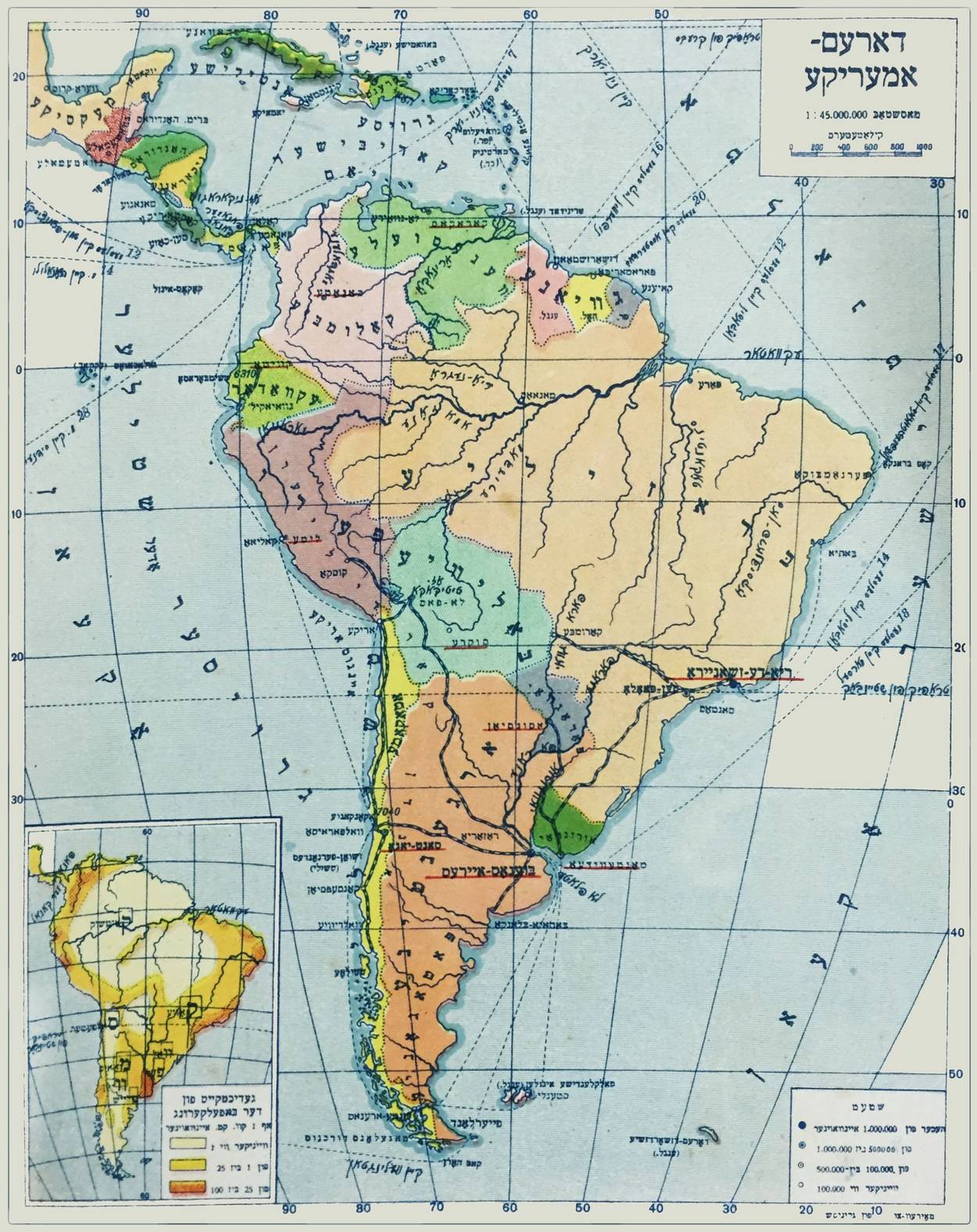

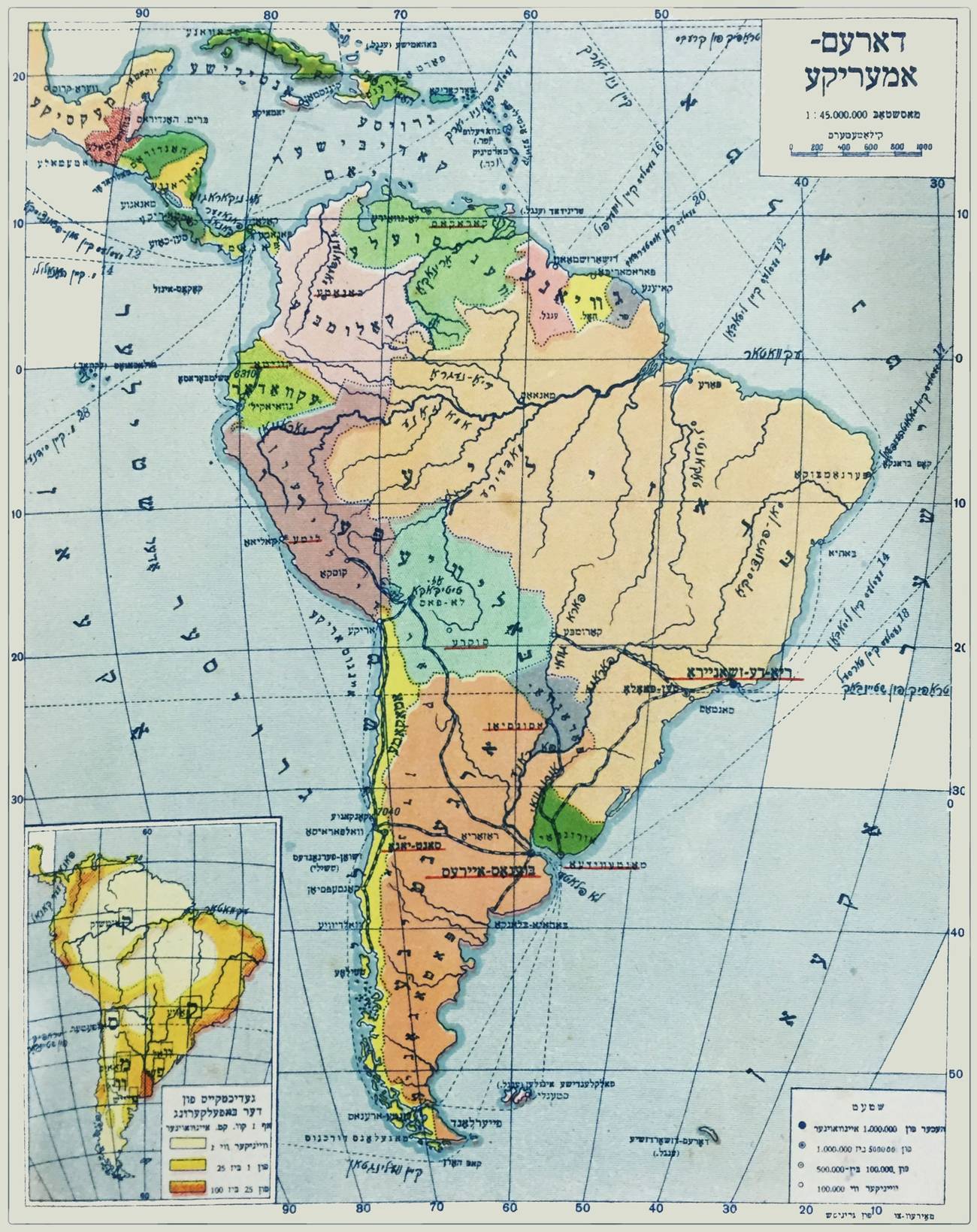

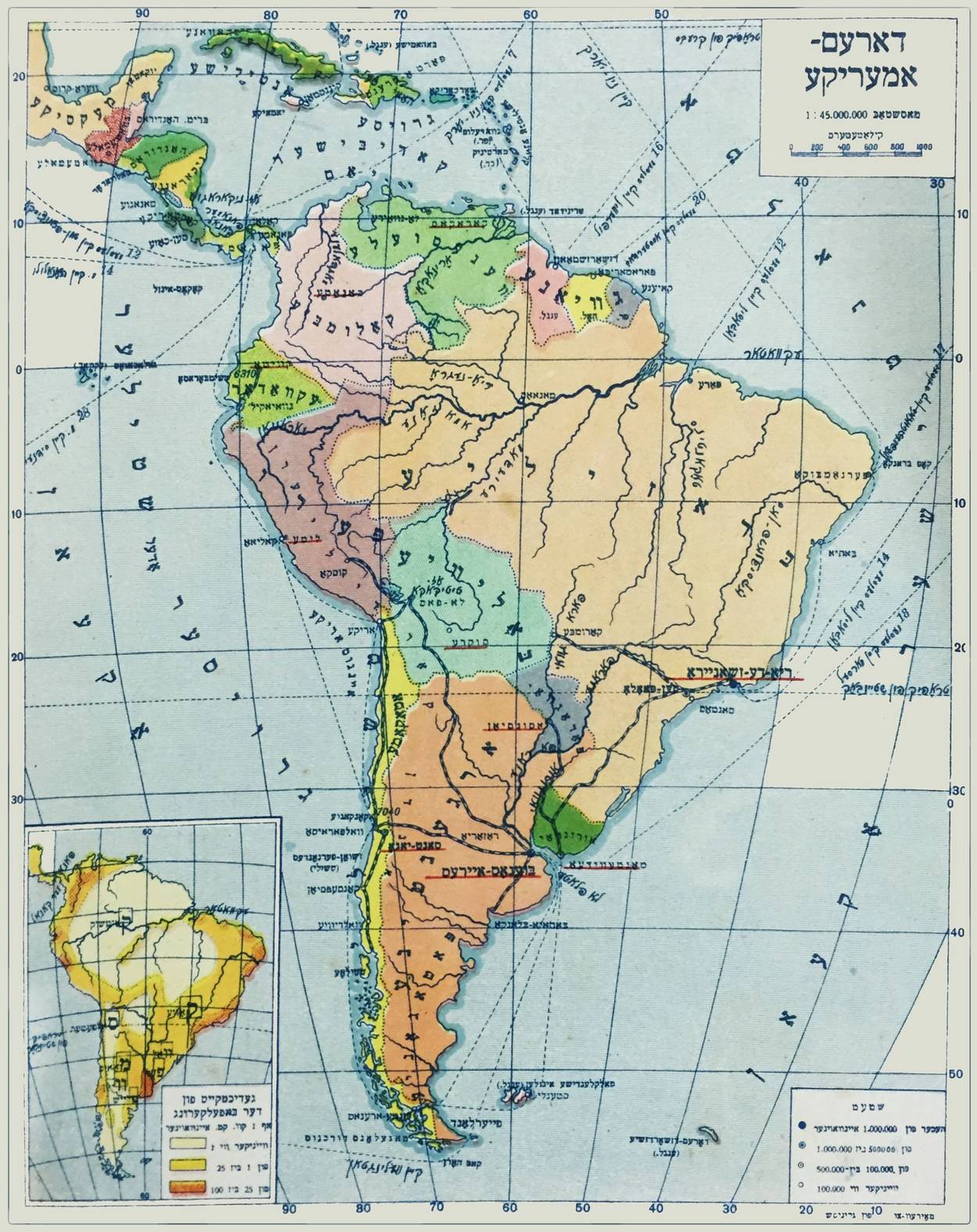

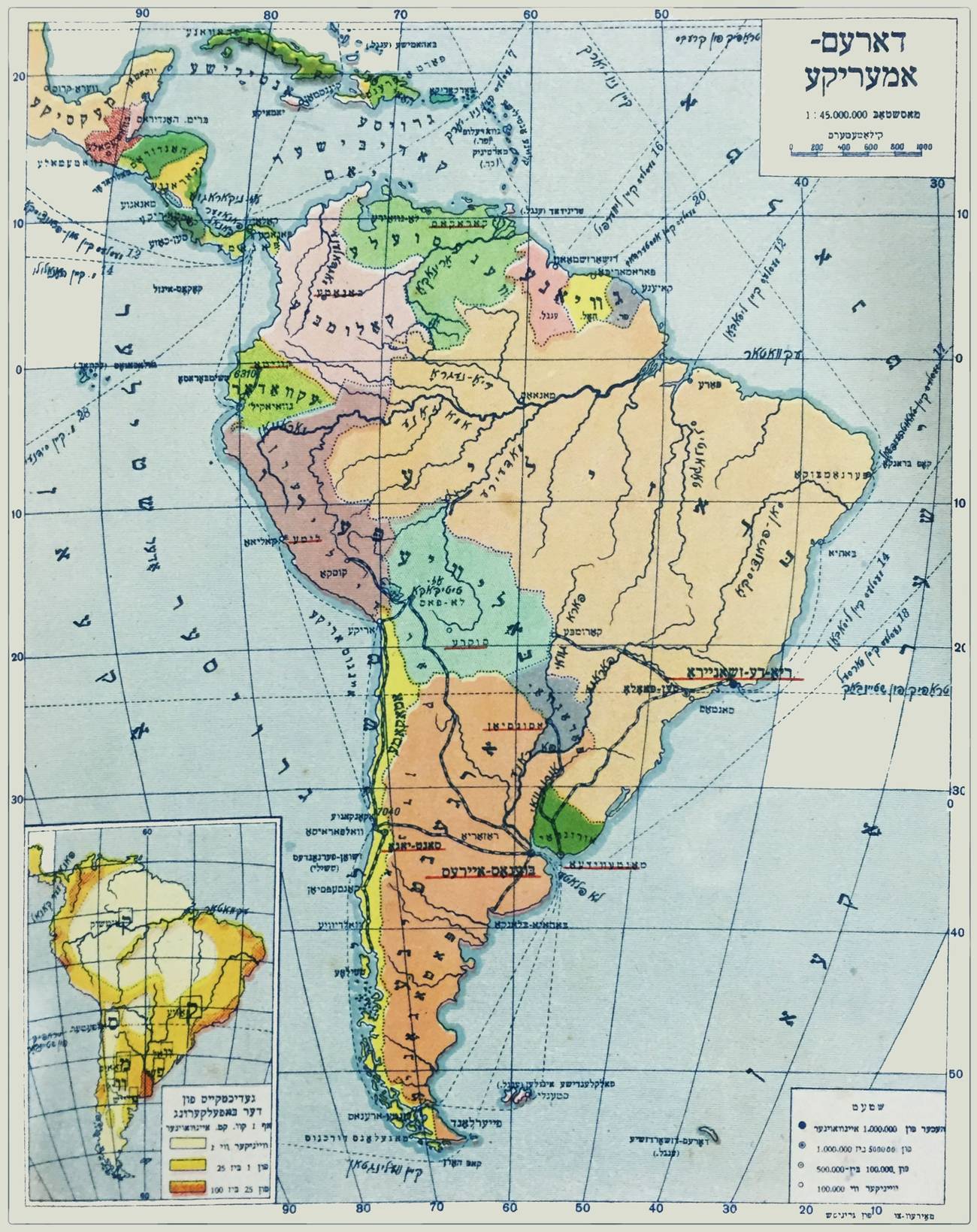

In February of 1898, 4,824 immigrants arrived at the port of Buenos Aires: 2,919 Italians, 1,284 Spaniards, 166 French, 137 Turks, 84 Russians, 47 Austrians, 46 Germans, 42 Brits, 35 Portuguese, 23 Swiss, 15 Belgians, 13 Moroccans, five Americans, four Danes, three Swedes, and one Dutch. In Buenos Aires, 1 out of every 2 people on the streets had been born elsewhere, at least one ocean away.

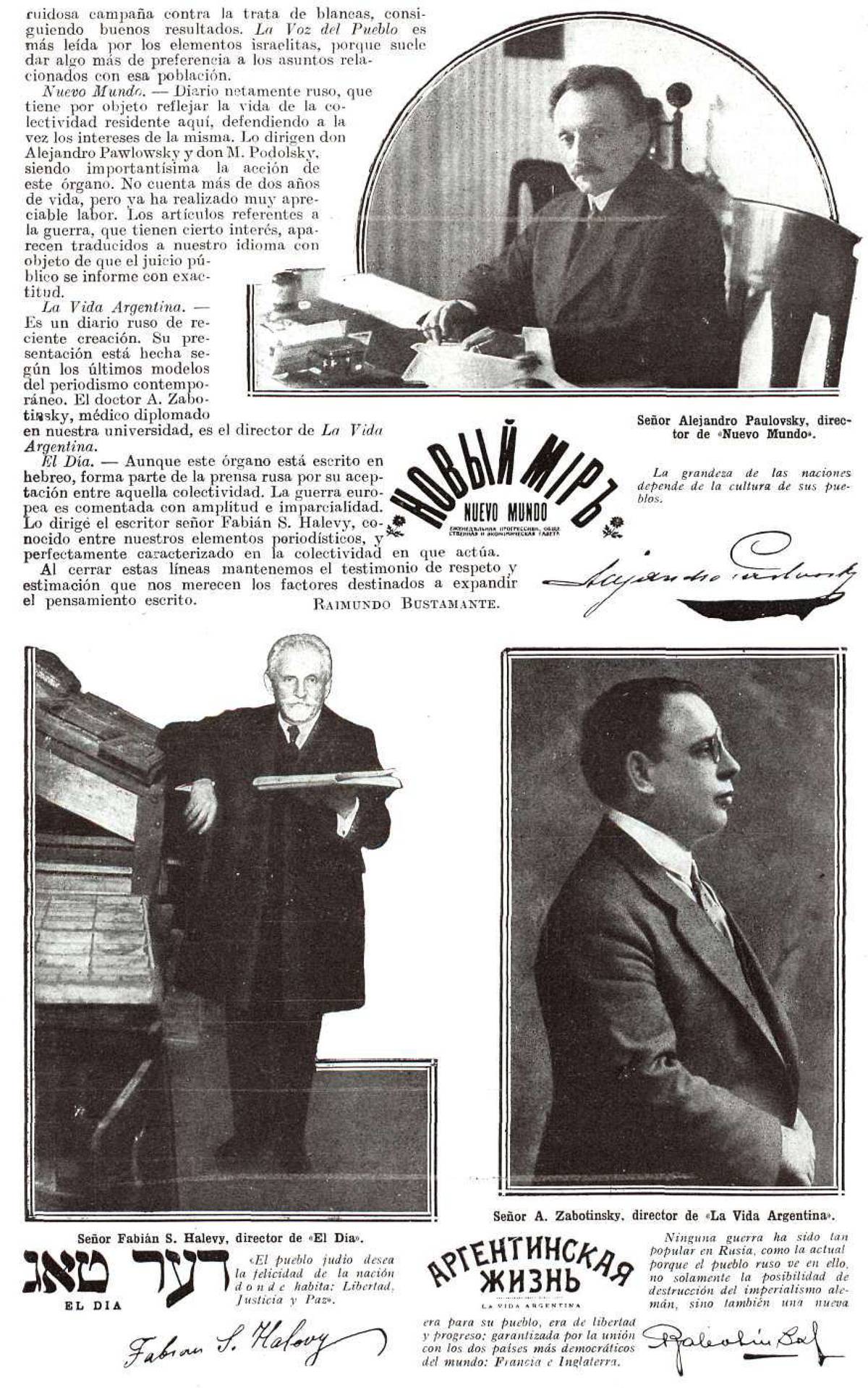

Many of these communities had their own newspapers; the Jewish community did also. We know a lot about Argentina’s Yiddish pioneers thanks to Pinie Katz, a journalist who years later, in 1929, published in Buenos Aires a book titled Tsu der geshijte fun der idisher dyurnalistik in Argentine (with a Spanish title, Apuntes para la historia del periodismo judío en la Argentina), which tells the story of the Jewish press in Argentina between 1898 to 1914. That last year, David Goldman wrote in his book Di Yuden in Argentine (Jews in Argentina) that there was a “mass of corpses in Argentina’s literary cemetery,” referring to the high number of newspapers that were short-lived. Goldman calculated that up until 1914, some 40 newspapers had sprung up, and in 1951 the magazine Der Shpigl defined that early period as “the heroic era of Jewish journalism” in Argentina.

In his book, Pinie Katz told us about those restless Quixotes and their newspapers, their reports, their intrigues, the debates they prompted within the community, and their relationship to Argentine society. However, over the years Katz and the pioneers he chronicled became figures blurred by time, or as in most cases, completely forgotten. This was especially true given that they wrote and published in Yiddish, which isolated them from anyone who didn’t speak the language. Now, though, we have translated Katz’s book into Spanish, appearing under the title La caja de letras: Hallazgo y recuperación de “Apuntes para la historia del periodismo judío en la Argentina”, de Pinie Katz, or The Box of Letters: Discovery and Recovery of “Notes for a History of Jewish Journalism in Argentina,” by Pinie Katz.

Here are eight portraits of some of the key players, based on Katz’s reporting.

He created the first Yiddish newspaper in Argentina, Der Viderkol (The Echo), at the age of 20. The paper was a precarious enterprise that lasted only three editions but established his journalistic credentials. Since then, Hacohen Sinay has been known as der pioner fun der yiddisher dyurnalistik in Argentine. Since no Yiddish typographical elements were available in Buenos Aires when he founded the paper, Hacohen Sinay made lithographs, creating individual etchings for each page. This made Der Viderkol something like a work of art, difficult to produce and requiring significant manual labor. The first edition appeared on March 8, 1898, and was an instant success in the area.

Mijl came from Moisés Ville, an agricultural colony of Russian Jews in the middle of nowhere, where his father, a well known rabbi, had led a failed rebellion of colonists against the administration. His father’s work galvanized him to create the first edition of Der Viderkol, which was four pages and filled with columns denouncing all the injustices of Moises Ville. He ceased publication after producing two more editions. “I couldn’t continue my work on Der Viderkol because I was sick for two months,” wrote Mijl years later. He never specified the illness.

For the rest of his life, Mijl worked as a teacher, journalist, and writer. As a journalist, he created several other publications and contributed to some 50 others from Argentina, America, and Russia. As a fiction writer, he never got far, though in his final two decades, he wrote memoirs about the first Jewish communities in Argentina.

Zalmen Reyzen, an important scholar of Yiddish culture in Eastern Europe, traveled to Argentina to meet Mijl. He wrote in a letter in 1932: “Even though you are still a young person, you’ve had such an intense life, with such important moments as a pioneer of the community and the Jewish culture of Argentina, that it falls to you to teach the current generation that knows so little of all this!”

For the last 14 years of his life, Mijl worked as an archivist at IWO, Buenos Aires. He died on Aug. 8, 1958.

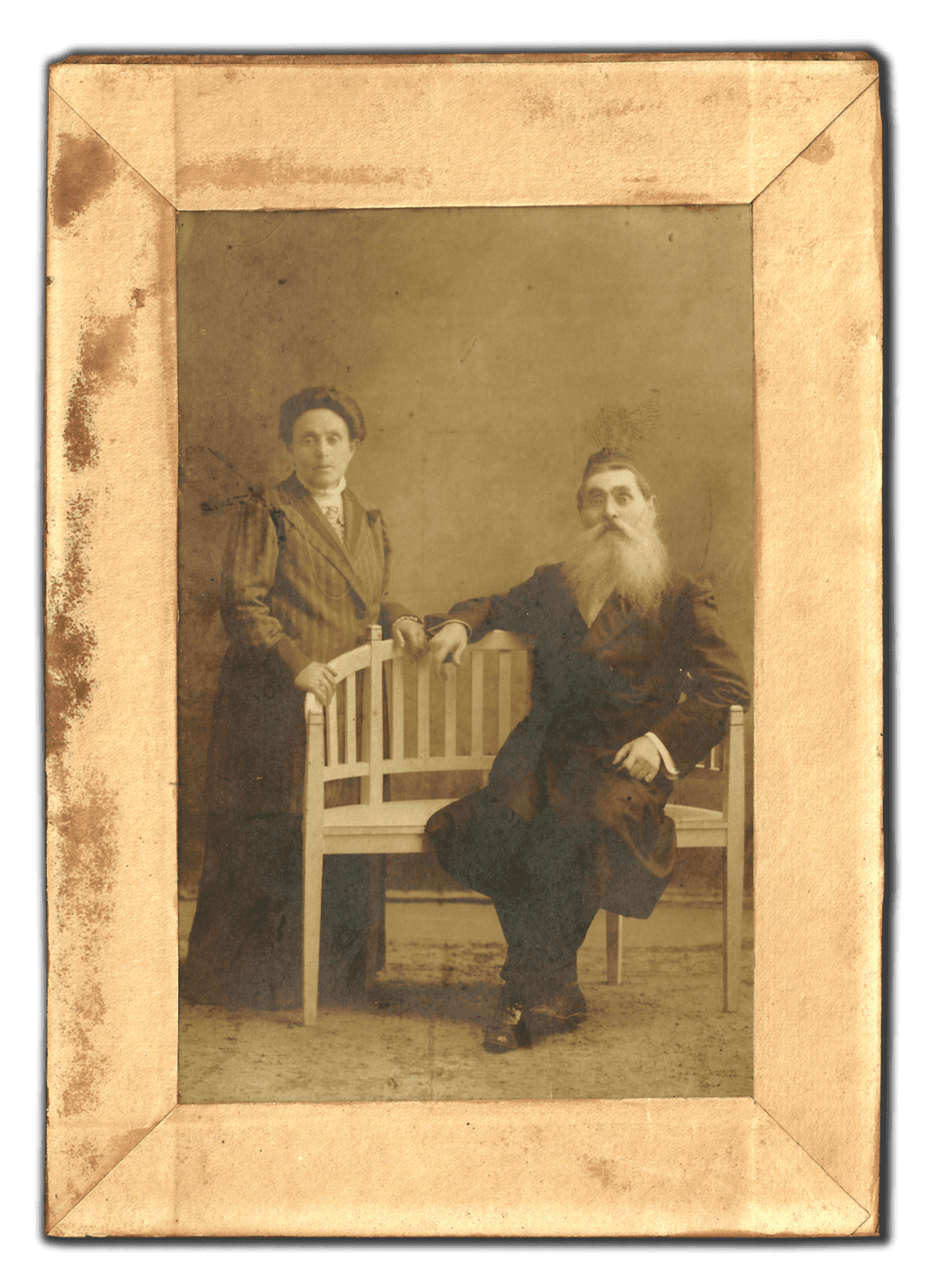

Mordejai, Mijl Hacohen Sinay’s father, was a rabbi and the son of a rabbi, born in Zabłudów, near Bialystok, in 1850. Orphaned at age 3, he was raised by his poor, ultra-Orthodox uncle, and then by another uncle, who brought him to Grodno, Belarus. A brilliant student, Mordejai trained to be a rabbi and worked for a variety of newspapers. He also wrote for Ha-Melitz and Ha-Zefira, which were covering agricultural colonies across the American continent.

As the Haskalah grew, Mordejai led a new Zionist movement, Jibat Zion, in Grodno. “He dedicated money and time to the ideal and was loyal to it over his entire life,” wrote his son. “In 1894, he left Russia and came to Argentina. What moved him to leave? Problems in Russia and the desire to see his children work the earth for a productive life.” Mordejai worked as the community leader and educator for a group of 42 families that emigrated from Grodno to Moises Ville. The trip was supervised and financed by the Jewish Colonization Association (JCA) of Baron de Hirsch, whose plan was to move millions of Russian Jews to rural South America.

But shortly thereafter, in 1897, in Argentina, Mordejai led a rebellion of colonists against the administration, protesting mistreatment and lamenting their inability to pay land debts due to plagues and damaged crops. Mordejai and two delegates traveled back across the Atlantic to the Paris headquarters of the JCA to appeal directly … but they failed. The local mutiny was put down by police, and he moved his family to Buenos Aires, where his son would document these events in Der Viderkol.

Despite that defeat, Mordejai remained tireless: In the following years, he defended the JCA, served as one of the first local Zionist leaders, and wrote op-ed style pieces for his son’s paper.

Vermont was the founder of Die Volks Stimme (The Voice of the People), the second Yiddish periodical in Buenos Aires. Launched on Aug. 11, 1898, the same year as Hacohen Sinay’s, the journal ran until 1914, covering topics from world news and local politics to Jewish community life and crime.

Vermont was a “savage journalist,” and a “journalist of chaos,” wrote Pinie Katz. According to Katz, he was one of the most controversial agitators of his day, whose influence was fundamental in the development of early Argentine Jewish journalism. Shmuel Rollansky, of the Buenos Aires IWO, agrees: “He was the first to produce an Argentine tabloid paper.”

Not much is known of Vermont: He was born in 1868 in today’s Romania, and his father was a kosher butcher. He is said to have studied in a school run by Greek priests that doubled as a home for disadvantaged youth, and to have lost his Judaism while living in various cities in the Balkans and then London, only to rediscover it after moving to Buenos Aires. He was a no-frills man who lived off only two coffees a day (according to Katz) and inhabited a small, dark room where he used newspapers for blankets.

In “Abraham Vermont: Memoirs of a Very Interesting Person,” an article in Der Shpigl, Mijl Hacohen Sinay remembers Vermont’s notable appearance: thin, of a pallid complexion, with cloudy, sickly eyes, sunken cheeks, a pointed nose, and fat lips. “Voltaire’s proverb applies,” wrote Hacohen Sinay. “If Vermont didn’t exist, it would have been necessary to invent him.”

Although he gave everything for his journal, Vermont was hardly an unimpeachable champion of the press. He was well known for getting involved in personal problems, intrigues, and gossip. “It was just as easy for Vermont to praise someone in his periodical one day as to insult him in the worst manner the next,” Katz writes. He was also thought to be involved in sex trafficking, like other Jews of the day, though Katz doesn’t give that rumor credence.

Vermont died in 1916, leaving behind a complicated and colorful legacy.

Levin lived in Buenos Aires for only two years before moving to Brazil, where he worked as a doctor. But in those two years he battled Abraham Vermont with a newspaper called Der Pauk (The Drum), which first appeared in 1899. Zalman Levin was the editor, and Mijl Hacohen Sinay occasionally wrote for the paper. Der Pauk was a satirical paper, but Levin’s humor consisted mostly of attacks on Die Volks Stimme. In fact, Levin published pamphlets like “Vermont and the Tmeeim,” using the word for the religiously impure to reference traffickers of women, and “Judgment of Vermont in the Afterlife.” Thanks to the pamphlets, Hacohen Sinay writes, “Vermont, who had been a hero to many for some time, stopped being considered one.”

In 1901, a year after the last edition of Der Pauk had come out, Levin found a new medium to continue his persecution of Vermont: He organized a play titled Vermont oif der catre, or Vermont in the catre, which is a small rustic bed. It ran in a salon, with Levin playing the role of Vermont. “This was the first instance of Yiddish theater in Buenos Aires,” writes Katz—no small feat given that Yiddish theater went on to have a grandiose presence in the city. Mijl Hacohan Sinay also remembers the play: “Levin imitated Vermont so accurately, in his costume and his mannerisms, that the public couldn’t believe it wasn’t Vermont himself.”

“Each of his articles stood out as virtuous, a breath of fresh air after the daytchmerish and Balkan wordiness of Vermont,” writes Pinie Katz. In an era of pre-modern newspapers, Joselevich was a wealthy man who in his youth in the 1880s had worked as a locksmith and was part of the socialist intelligentsia in Warsaw and Odessa, where he met Mendele Mocher Sforim and Sholem Aleichem. In Buenos Aires he worked crafting objects out of nickel, which made his fortune. “He then left socialism and began agitating with his love for Zion,” Katz writes.

He launched Der Idisher Fonograf, a newspaper from 1898, writing Zionist propaganda using his excellent Yiddish, which he edited himself so that no one else could ruin his columns. Katz writes, “Joselevich was a very meticulous, humble, quiet, and careful person who cared about honor,” which were traits not shared by other journalists and editors of that generation.

In addition, he became a local Zionist leader. “As he aged,” Katz writes, “and as his Zionism grew, Joselevich, with his silver beard, would get close to the new young immigrants, creating the left-wing Zionist organization Tiferet Tzion.” From there, in August 1908, he founded the newspaper Di Idishe Hofenung, or The Hope of Israel, as it was officially called in Spanish.

In the fifth edition, from October, Joselevich began serializing Sholem Aleichems’ Di Goldschpiners, which the paper had commissioned. “The manuscript arrived with a funny note from Aleichem,” Katz recalls. “The letter made the rounds at the organization. Even I, who wasn’t really a member there, had it in my hands to read once. As I remember it, it was written on very thin paper, like cigarette paper.

Halevy was on an agricultural colony in Entre Rios, working as a schoolteacher for the Jewish Colonization Association, when Soli Borok—the richest Jew in Buenos Aires—asked him to be the editor and publisher of the paper Der Idisher Fonograf. The Fonograf had launched on the same day as Die Volks Stimme, Aug. 11, 1898, and as such shared the title of second Yiddish newspaper in Argentina.

Fabian Sh. Halevy (the “Sh.” is for Shrayber, writer) was a dedicated student of Torah, born in Płock. He was cultured, and understood the theories of Alexander von Humboldt’s and Zelik Slanimsky’s articles. He wrote for Albanon, Ha-Magid, and Ha-Zefira, and spoke Russian, German, French, and Spanish, but his Yiddish was only passable. Shlomo Leibeschutz, another man of culture, explained that it wouldn’t be a problem: “Just write in German using Hebrew letters and that’s the jargon.” And indeed that’s how it worked.

Der Idisher Fonograf was never sensationalist, just the opposite. Shmuel Rollansky, writing in Dos yiddishe gedrukte vort un teater in Argentine, notes that “The editor of Der Idisher Fonograf was a man of peace. A verse out of a book or a German writer moved him more than everyday life, and it showed in his paper. He wasn’t one to speak of the tmeeim [the impure], or seek out a war with the bureaucrats of the JCA. What would someone living a pious Jewish life need to know about that stuff?”

A man like that lacks enemies and odysseys, and in his later years, Halevy set to translating Jean Racine’s lyric drama Esther into Yiddish, and writing a novel, Der Farlorener (The Last). He died in Buenos Aires in 1932.

“He was the most exuberant founder of periodicals in Yiddish and a pioneer of the Jewish press in Spanish,” wrote the historian Boleslao Lewin of Liachovitzky. Shmuel Rollansky put it this way: “Liachovitzky was the first to bring strength and personality to the work. His creations were so unique that no one could remain neutral about them.”

Born in Pruzhany, near Grodno, in 1874, he emigrated to Argentina in 1891. “From 17 years old, the pen was my colleague,” he wrote in 1919. “My articles found audiences in Hebrew, Polish, Russian, German, and Spanish.” In Argentina he got his start at Mijl Hacohen Sinay’s Der Viderkol, and later founded weeklies and dailies. “I used all the letters of the alef-bet, and all those of the ABCs, using 6 different pseudonyms. I also worked in the Argentinian press in Spanish, and I edited the first bilingual Spanish-Yiddish papers.” Between 1898 and 1905 he collaborated on Die Welt, Theodor Herzl’s paper, sending reports on the Jews of Argentina. He also helped create charities, libraries, and schools. In his book Tsu der geshijte fun der idisher dyurnalistik in Argentine, Pinie Katz notes, not without irony, that Liachovitzky was so generous and expansive that he was simultaneously an anarchist, a socialist, a Zionist, and a friend of Argentine political power.

The first Yiddish daily to appear under Liachovitzky’s direction was Der Tog, which launched on Jan. 1, 1914. Pinie Katz was one of the collaborators, and he recounts that shortly after there was a scandal when some money destined for starving colonists was robbed. “All the money that came into the newspaper, from readers or from advertisements, would get lost if it landed in Liachovitzky’s hands.” Liachovitzky left Der Tog in November of that year, to found Di Ydische Zaitung, an important Yiddish daily that lasted for several decades.

Author of an intense, agile, and indiscreet history of the Jewish press in Argentina, Tsu der geshijte fun der idisher dyurnalistik in Argentine (Apuntes para la historia del periodismo judío en la Argentina), which was published in Yiddish in Buenos Aires in 1929. Katz was a journalist, writer, union leader, creator of cultural institutions, and translator (among many works translated to Yiddish he counts Cervantes’ Don Quijote and Sarmiento’s Facundo). He was, according to Shmuel Rollansky, “a rabbi of letters” and “the last of the first of the Jewish press in Argentina.”

Born in 1881 in Groseles (Grossulov, today known as Velikaya Mikhailovka), near Odessa, he arrived in Argentina in 1906, after the defeat of the socialist revolution in Russia in 1905. In South America, before becoming a journalist, he worked as a painter and Jewish educator. Zalmen Sorkin, the leader of the Zionist workers organization Poalei Tzion, brought Katz into the movement, which led to his writing for some papers. In 1914, he joined Di Ydische Zaitung—a huge paper—but after a labor strike he left with a group of journalists to found in 1918 Di Presse, a leftist pro-Soviet paper, which he directed until 1952. Di Presse became the main competition to Di Ydische Zaitung for nearly half a century. As a journalist, Katz distinguished himself, according to an obituary that ran in Mundo Israelita, “for the gallantry of his language, the sobriety of his style, and the sharpness of his commentary.”

Katz was always active in society, and in April of 1941, he founded the Argentine branch of the ICUF (Idisher Culture Farband, the federation of Jewish cultural institutions). Four years prior he had been in Paris, at the inaugural world congress of that federation, which was born of a proposal from Jewish intellectuals in the French Communist Party, in service of anti-fascism and Jewish culture, and against antisemitism. Katz represented 23 Argentine and five Uruguayan institutions. As a communist, though, he lived through a period in which the Soviet Union’s hostility to Jews was difficult to hide from, or explain away.

Katz died Aug. 7, 1959, but years before that he was able to oversee the publication of his complete works in nine volumes, a privilege reserved for few writers.

Translation from Spanish by Matthew Fishbane.

Javier Sinay, a Buenos Aires-based journalist, is the author of three books, including, most recently, Los Crímenes de Moisés Ville. The book will be published by Restless Books as The Murders of Moisés Ville in February of 2022.