In a Box of Old Letters, a Romance Is Reborn After 70 Years

After I found a collection of love letters at a flea market, I spent years diving deep into another family’s relationships

I was trawling San Francisco’s Alemany Flea Market one summer Sunday in 2002, looking for old stamps for a crafts project, when a vendor pointed at a cardboard box beneath his table. “I bought it at a storage locker auction and haven’t had time to go through it,” he said. I unfolded the top flaps and spotted a postcard from the 1940 New York World’s Fair. Visions of eBay sales danced in my head as I asked the vendor how much he wanted for the whole box. He asked for $50. I had $35. We called it a deal.

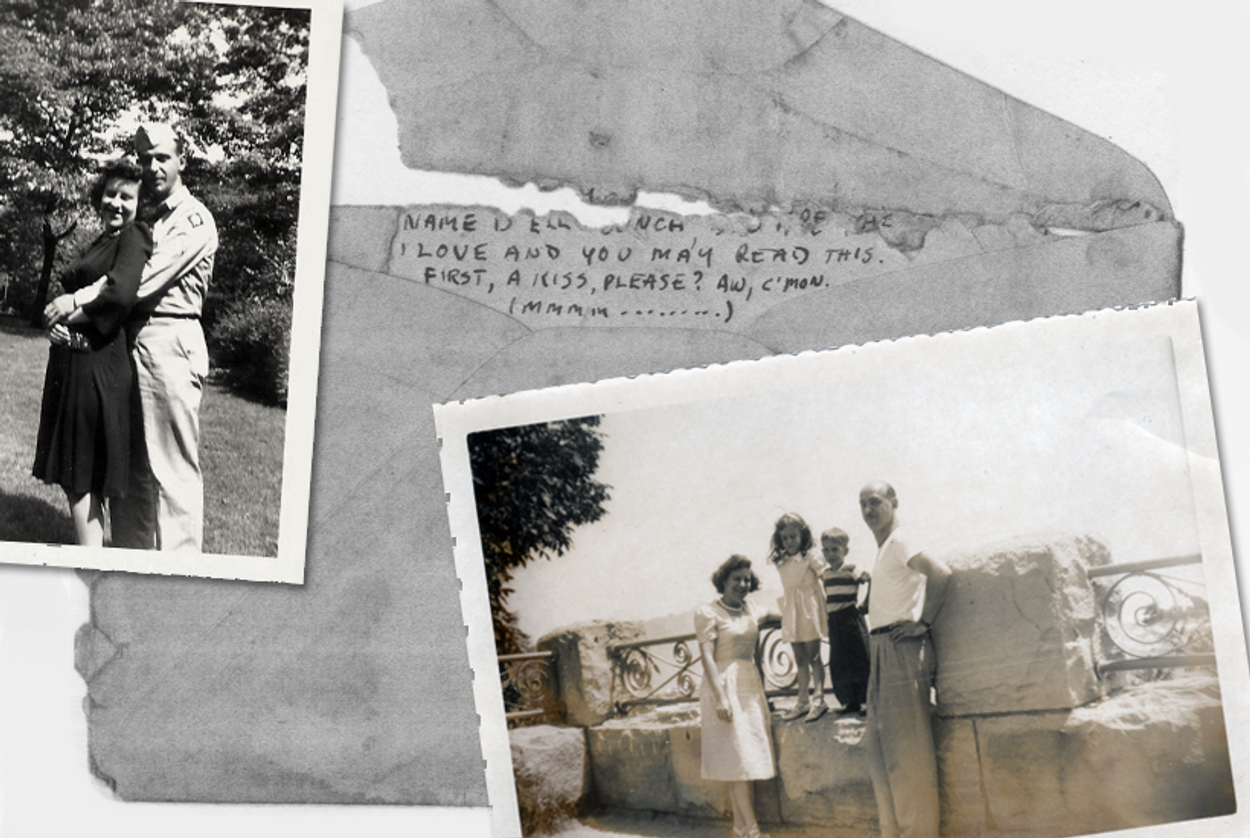

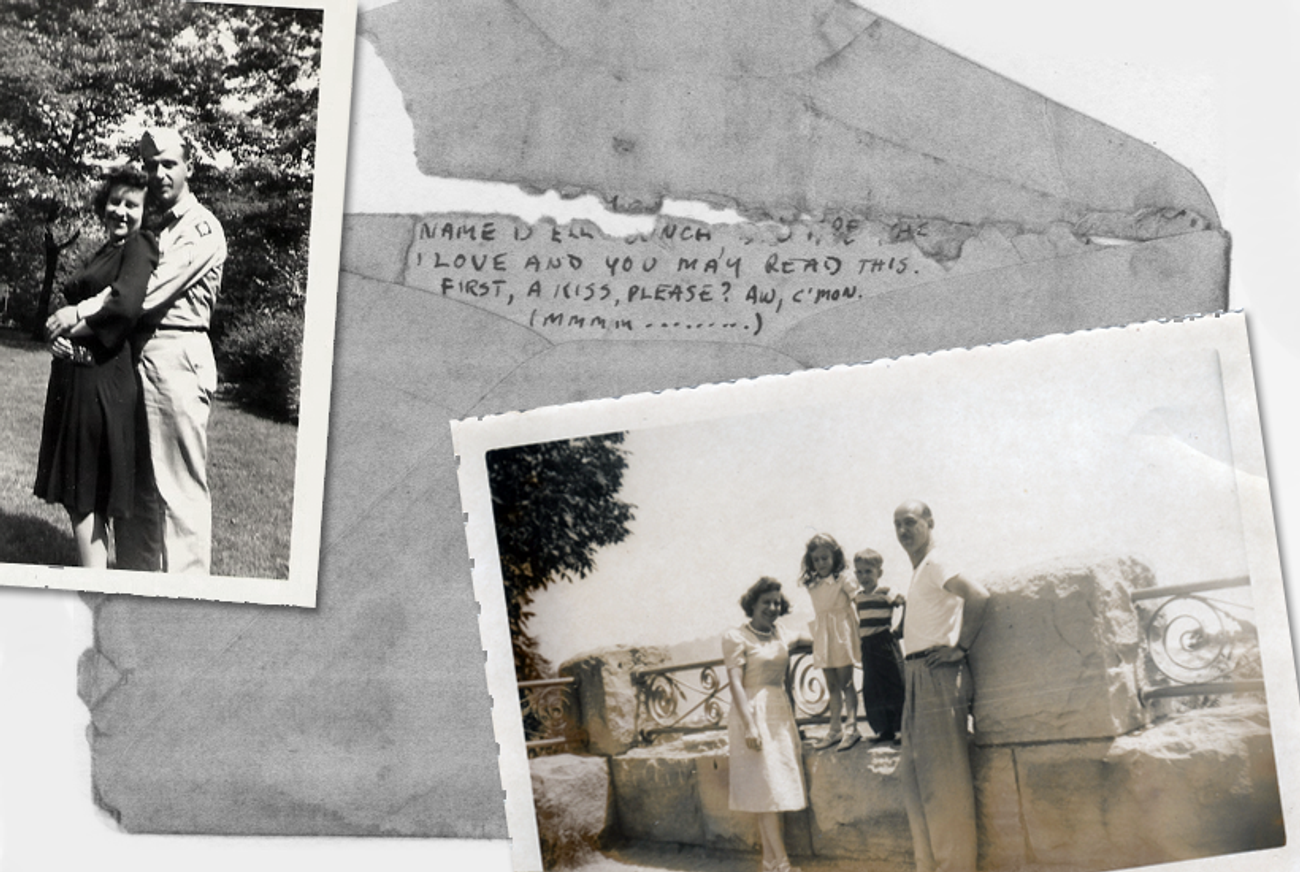

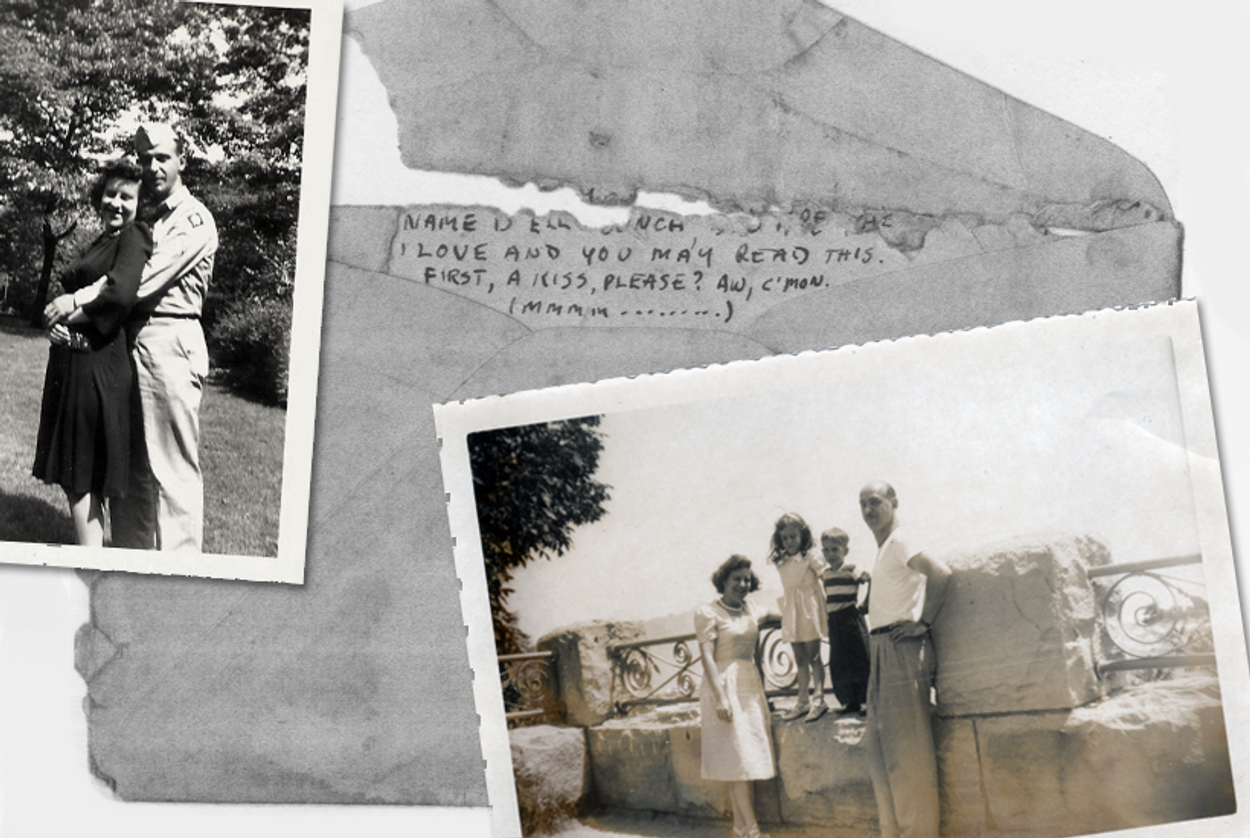

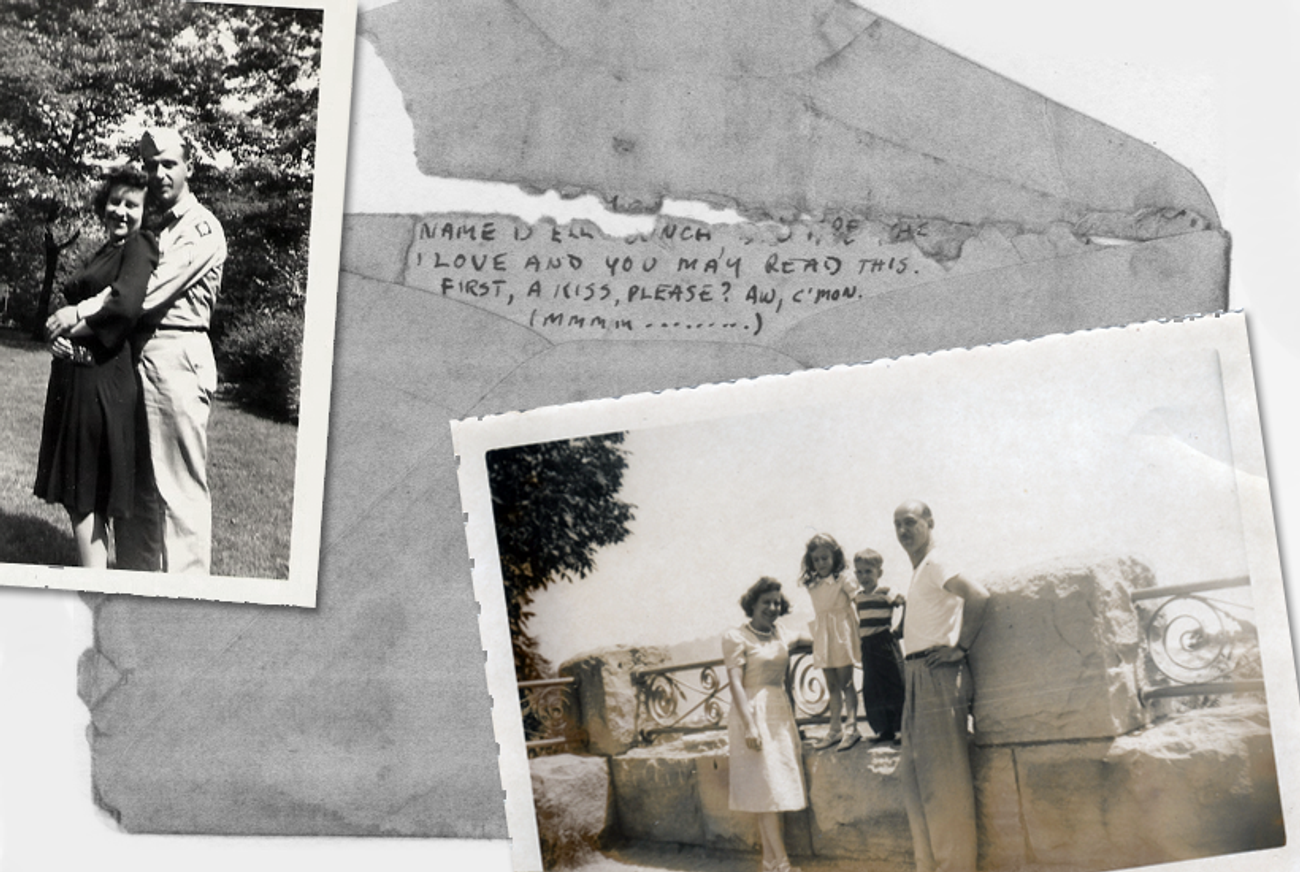

When I got the box home and delved into its contents, I realized I’d stumbled on more than just a flea market bargain. It contained 30 years of mementos, all from a single family: report cards, newspaper clippings, holiday greetings, notes from summer camp. Most of all, though, it contained letters—almost 100 of them dated 1940 to 1943, all from Leon Rosenberg, first addressed to Elinora Garfinkle and then, tellingly, to Elinora Rosenberg. Long-ago exposure to damp had turned a few into stained, smeared papier-maché lumps, but the rest were still perfectly legible. I pulled one out at random and started to read:

Last night another fellow and I had nothing to do … So after a while we drove to the Joosh Center just to see what was going on. There was a dance in progress and a number of not bad (not good, but not bad) females hanging around in the lobby. Already I see that “a-hah!” look gathering in your blue, blue eyes. Sure enough they was two dames sort of cuting around. So Penny — the guy with the car — followed closely by your faithful, sidles up to them and commences to howyou.

Ennehoe — and this is the good part (from your viewpoint) — the one who fell to me (definitely not for me) was married. It appeared her hubby was in N.Y. They were itching to gobitchingdancing, but neither Penny nor I were going to pay their entrance fee since it didn’t look like we’d get nuttin. So after gabbing quite a while we proposed a ride and something to eat. Well sir, you know how the latter proposition never fails. It was nice riding in the new car even if I did have to hold the married gal on my lap. Guess what, sweetheart dearest precious doll darling I love only you nobody but you sweet you (how the hell did I get into this?) The married gal turned out to be a political ‘lantzman’! Knew the songs and everything. While we were eating (she had a malted, I, a full dinner) she told me all about her hubby doll and I told her all about my Ellybunch.

A hint of leftist Jewish politics, a suggestion of long-distance romance, a compulsively readable voice—it was all catnip to my inner voyeur. I sorted the letters in chronological order by postmark and dug in.

All I was hoping for was a satisfying wallow in a stranger’s long-ago romance. I had no idea that I would meet that stranger and spend years diving even deeper into his family’s personal and political history.

***

Leon moved to Washington, D.C., in September 1940 to take a job at the U.S. Census Bureau. He wrote to Elly back home in Cleveland almost every day for the next nine months, reminding her that his goal was to “put away as much green sunshine as possible so that our marriage plant may blossom and bloom this summer.”

The letters paused in June 1941, just days before their wedding, but they started up again shortly after the newlyweds’ first anniversary. Leon was now a private in the Army, being moved from one stateside post to the next, while Elly remained in D.C., working as a secretary at the Pentagon.

Leon clearly identified as Jewish—declaring a movie “SHTINKTABISSLE” and planning to “come home for Pesach”—but he also loved pork chops and agreed only grudgingly to be married by a rabbi, after which he insisted he would worship only his new wife. He poured on the endearments, but not without the occasional tactical error, as when he told Elly defensively, “Does wanting your sweetheart to look as ravishing as possible— and therefore suggesting that the hip-line be watched—mean that her boychik doesn’t love her or ‘loves her less?’ ”

He wore his heart on his sleeve politically as well as personally, urging his future wife to involve herself in a Marxist study group and wishing her sister a happy birthday by saying, “May you and all your children’s children celebrate a good number of them in a new type society.” Yet he also understood the value of discretion. If he wanted a permanent Civil Service position when he and Elly returned to D.C. after their wedding, he needed to avoid running afoul of the Smith Act, the 1940 law that penalized membership in or affiliation with the Communist Party with fines, prison time—and a ban of up to five years on working for the Federal Government. With a background check pending, he warned Elly that they needed to stop writing about politics:

Keep cool about the investigation. They can learn naught more than they already know which is everything except factual proof. What is significant, however, is their distinction between present affiliation and past. This is a very hopeful note as my present is worthy of the D.A.R. (sic!-ening) One new precaution, however. From this letter on all replies to me must contain no references to people or ideas connected with the above.

Their caution must have paid off, because although the letters pause just before their wedding, they resume with Elly living and working in D.C. Unfortunately, Leon was not. A month after the couple’s first wedding anniversary, he was in basic training at Fort McClellan, Ala., grumbling about how the heat there made him “puff, pant, perspire, profane, piss, etc.” as he learned to shoot a rifle and ram a bayonet through a straw dummy. In mid-1943, he wrote from Fort Collins, Colo., describing his first encounter with the enemy: “We have NAZI prisoners out here now! They work at the G.I. Laundry and I watched them line up after work to march to their stockade. The dirty, murderous bastards! They look like ordinary ‘pool-room’ hoodlums to me.”

That was his last letter. I was left hanging at what felt like the middle of the story. The other papers in the box proved that Leon had survived the war and returned to Elly to raise a family. A handful of holiday cards proved the Rosenbergs had spent the 1950s in Cleveland. A daughter named Robin popped up in a note from summer camp, while a son named Roger appeared as an elementary school report card. These scraps only hinted at Leon and Elly’s postwar life, but couldn’t explain what happened in the decades since. Nor did they reveal how Leon’s letters had ended up in an abandoned storage locker half a continent away. Did his children know these precious family heirlooms still existed? Did the family itself still exist? If so, I thought I owed it to them to give the letters back—but how?

***

By the time I finished reading, I felt like I knew Leon and Elly, but I still had no clue how to find them other than calling every Rosenberg in Ohio, a notion I gave up as soon as I discovered how many there were. I was seriously considering hiring a private investigator when I discovered a loose sheet of paper dated 1965 at the bottom of the box. Written to “Mom and Dad” and signed “Robin” in a young woman’s looping scrawl, it talked about studying in Paris through the University of California-Berkeley.

I called the school’s alumni office and asked if they had any record of a student named Robin Rosenberg who would have graduated some time in the 1960s. As vague as my request was, it was enough. A few audible keyboard clicks later, I knew that Leon and Elly’s daughter had graduated in 1966. I knew her married name. I even knew that the alumni office had her current address. Privacy laws prevented them from sharing it, but they were happy to forward something to her if I wanted. Later that day, I hurried to the mailbox with a note that began, “I’m hoping you’re the former Robin Rosenberg, daughter of Leon Rosenberg and Elly Garfinkle of Cleveland, Ohio. If you are, I have your parents’ love letters.”

Three weeks later, Robin called me. In an awkward, breathless conversation, she told me that the family had moved to California in 1960. Elly had died in 1998, never having told anyone that she’d placed a number of things in a storage unit. The very existence of the letters was news to her children—and their survival was news to Leon, who, to my astonished delight, was still alive. Better yet, he was living just a few miles from me, and he wanted to meet me.

Not long after, I met the entire clan—Leon, his two kids, and his two grandkids—at Spenger’s Fresh Fish Grotto, a Berkeley institution older than his letters. Over shrimp cocktails, I told him that half a dozen friends with whom I’d shared excerpts from his letters were willing to go on a date with him, sight unseen, on the basis of his writing skills alone. He hiked up his pants legs and exclaimed, “Boy, it’s getting deep in here.”

As I handed over the box of family papers, I told him that I had made photocopies of his letters so I could read them without further damaging the originals. I said that while I would destroy the copies if he wanted, I very much hoped he would let me write about them. He grinned, winked, and said he would give his consent if and only if I agreed to have lunch with him again.

Over the next two years, we had half a dozen “dates” to discuss the people, places, and events in his letters. Our conversations also included Elly’s childhood as an orphan, Leon’s as the son of a single mother, and Leon’s military service—he never saw combat, which he blamed on his politics, yet he spent his final months in the Army working as a clerk in Gen. Eisenhower’s Berlin office. He offered to lend me several obviously treasured and heavily annotated books about socialism. I declined those, but I eagerly accepted his loan of Elly’s diary from 1940, the year leading up to their engagement. Unlike Leon, whose letters were long and intended to be read, Elly was writing to herself in a diary allowing her just a few lines a day, but her take on their courtship suggests that she was the more practical of the two. On March 30, for example, she wrote, “I blasted all his dreams of our future happiness with some talk on ambition, vocation, & security. He felt he had no right to ask any girl to marry him but down deeper he feels that if I loved him enough I’d marry him on what he earns now & work too.” By the time he left for D.C. in late September, he thought they had an understanding if not a formal engagement, but on Nov. 13, she was writing, “I’m thinking of incompatibilities again—building up a case against him—or us. Oh my flexible moods. Which are right?” Still, the diary ends on Dec. 20 with a note that she “took care of personal stuff till late—to be ready for my Leon.” He arrived the next day and presented her with a ring.

***

Originally, I just intended to compile Leon’s letters into a book to show off the raw verve of his writing to other people who enjoy well-written letters as much as I do. As I started to transcribe them, though, I discovered they were full of references that would have made perfect sense to Leon and Elly, but demanded more research 70-plus years on. I found myself footnoting comments about leftist Jews in the 1930s, an asbestos heir who was a Kardashian of his day, and a teaching assistant at Elly’s university who eventually became an early opponent of McCarthyism in academia. At that point, I decided I wanted to write a book putting Leon’s letters (and Elly’s diary) into a larger context.

What makes these letters so compelling? It’s not just that there are enough to construct an entire narrative from them, or that they survived long enough for me to return them to their author, although those are both part of it. It’s also Leon’s distinctive writing style, which makes reading his letters like having an intimate chat across the decades. Top that with an undisguised political point of view that doesn’t get a lot of attention in popular depictions of the 1940s, and what you get is an irresistible combination: letters that are somehow commonplace and extraordinary at the same time. And their sheer besotted romanticism doesn’t hurt, either. I would marry a man who wrote to me like that, too.

Although Leon died in 2007, he and Elly are getting a second chance at courtship as I research their lives and the context they lived in. Over the last two years, I’ve used genealogy resources like Census data and vital statistics records to start building a family tree and timeline. I’ve spent hours online looking up everything from current photos of Leon’s first apartment in Washington to the reason why the Communist Party of the USA switched abruptly from opposing the war to supporting it. And of course, I’ve spent time talking to the couple’s children and grandchildren, both by email and in person.

Any awkwardness I might have felt about peering into the Rosenberg family history is long gone. The Rosenberg kids treat me like I’m part of the family—maybe a distant cousin, albeit one who knows a lot about their parents and is blogging about her research. Robin has chosen so far not to read the details of her parents’ romance, but she’s delighted to share old photos and always tells me when my research confirms or contradicts some longstanding family legend. Roger, who was afraid at first that the letters would reveal something he didn’t want to know, says the only surprise they contained was how head-over-heels his parents were about each other.

What continues to surprise me is how I stumbled across them in the first place. The family thinks that maybe, when the couple sold their large house in the early 1990s, Elly rented a storage unit for things that didn’t fit into their much smaller new condo. Since no one knew about it, no one continued paying the rent after she died, and the storage company would have auctioned off the contents after a few months. I may never know what happened to the letters in the four years between Elly’s death and my flea market find, but “ennehoe,” as Leon might say, I’m not sure that mystery needs to be solved. What matters is that I found them and saw them for what they were: a story that deserved telling, one that still doesn’t have an end.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Fawn Fitter has written hundreds of articles for publications ranging from Cosmopolitan to Entrepreneur, and one book, Working in the Dark: Keeping Your Job While Dealing With Depression.

Fawn Fitter has written hundreds of articles for publications ranging from Cosmopolitan to Entrepreneur, and one book, Working in the Dark: Keeping Your Job While Dealing With Depression.