Coming to America

Thirty years after making waves with her children’s book ‘Heather Has Two Mommies,’ author Lesléa Newman traces a young Jewish immigrant’s ‘Journey’

You wouldn’t think a sweet, celebratory picture book about a little girl’s first day of preschool would trigger such rage. Or maybe you would, if the little girl in question happened to have LGBT parents. When Heather Has Two Mommies debuted in 1989, it rocketed up the American Library Association’s list of most frequently banned and challenged books in the United States. In the 1990s, it was the ninth most contested book of the decade; it was burned, pooped on, returned to libraries with the pages glued together.

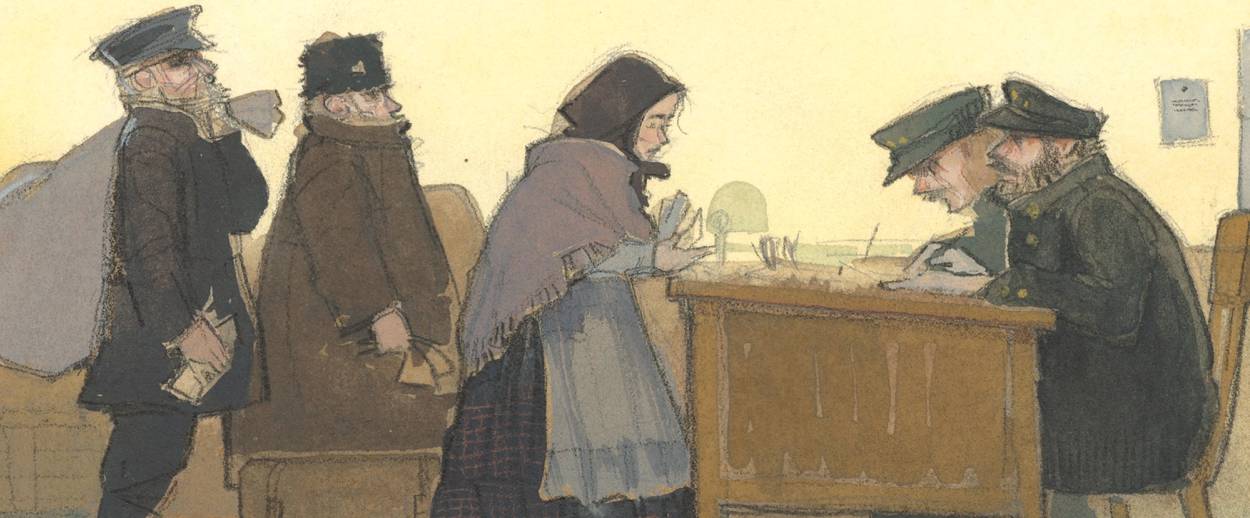

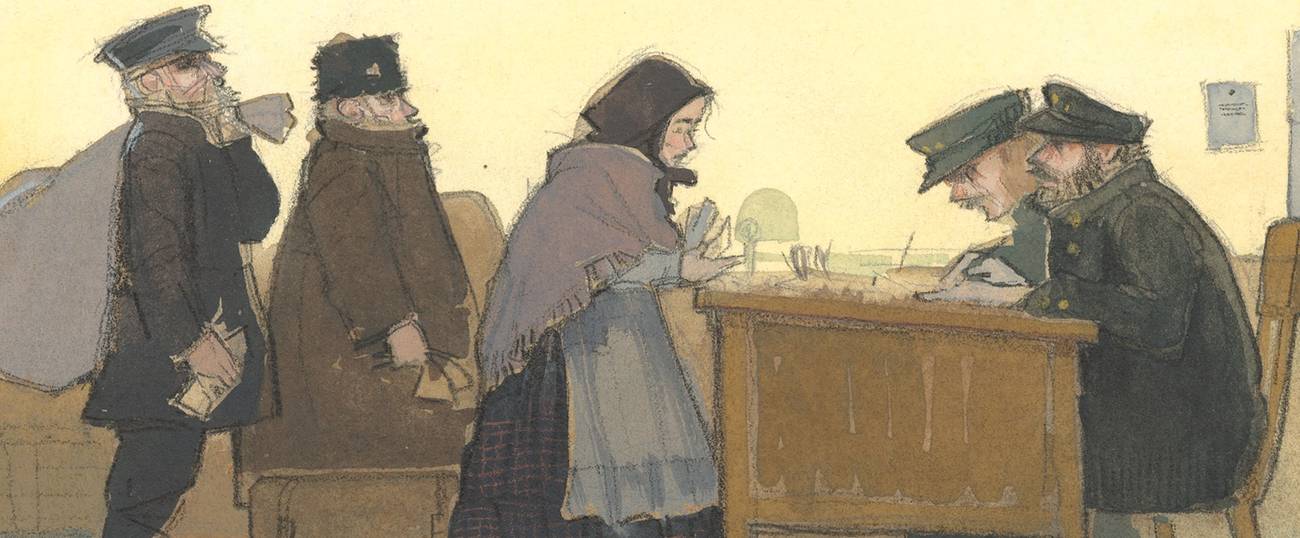

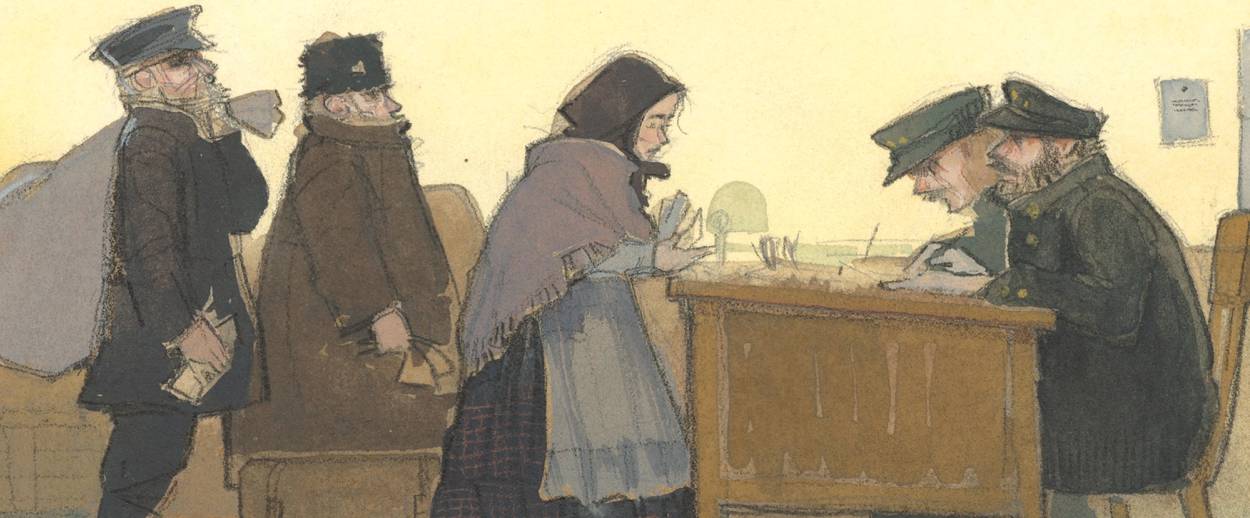

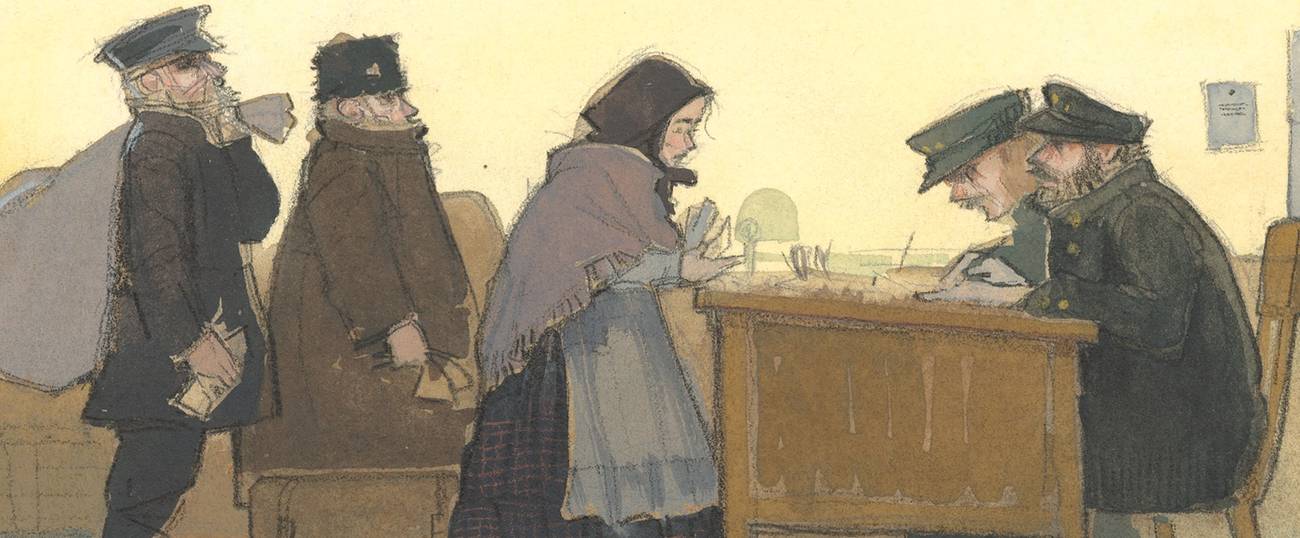

Heather’s author, Lesléa (pronounced Les-LEE-ah; you’re welcome) Newman, has never been deterred by haters. The author of over 70 books for kids and adults (several of which have appeared on Tablet’s best Jewish children’s books of the year lists), she looks forward. Her latest, Gittel’s Journey, illustrated by Amy June Bates, is the story of a little girl’s solo trip to America at the turn of the last century. Gorgeously published on heavy paper, sprinkled with Yiddish and spiked with bits of Newman’s own family lore, the book is luminous, both visually and narratively. Nine-year-old Gittel finds herself alone and at sea and afraid, but she keeps encountering kindnesses. And soft light pours through the windows at Ellis Island, making characters’ faces glow, as gorgeously stamped woodblock carvings and frames provide a sense of history.

Like Heather Has Two Mommies, Gittel’s Journey is a personal story. In an afterword, we see Newman’s Grandma Ruthie’s candlesticks (looking a lot like the ones that play a role in this story), learn about how Newman’s family friend Phyllis’ life story infuses the text, learn a bissel Yiddish, and read about Jewish immigration. Like Gittel, Phyllis’ mother crossed the ocean alone as a child and was reunited with family through collective effort. Published last week, the book has earned starred reviews from Publishers Weekly, School Library Journal, and Booklist.

“Gittel is special to me,” Newman told me in an interview. “Because words can’t describe what Phyllis means to me. She’s almost 91, and she’s beyond thrilled and astonished that the story of her mother as a poor young immigrant who came over with nothing has become this beautiful book that will be read and discussed by thousands of children and teachers and librarians.” Phyllis’ mother died in 1964, but her story will live on.

*

Newman lives in western Massachusetts with her wife, Mary, (who took the photo of the real-life candlesticks in the book’s afterword). Among her books—some Jewishly themed, some not; some LGBT-themed, some not—are the lovely short story collection A Letter to Harvey Milk, which became an unfortunately less lovely musical, and the autobiographical poetry collection I Carry My Mother, which follows a daughter as she copes with her mother’s illness, death, and yahrzeit. She’s written for teenagers: October Mourning: A Song for Matthew Shepard explores the Wyoming college student’s murder through a song cycle of 68 poems. She’s written for middle-grade readers: Hachiko Waits is a novel inspired by the true story of the Japanese dog who waited every day for a decade at the train station for his master’s return. And she writes frequently for little kids, as in Here Is the World, a beautiful spin through the Jewish year in verse, illustrated by Susan Gal; Sparkle Boy, illustrated by Maria Mola, about a little boy named Casey who loves shimmery skirts and glittery nails; and Ketzel the Cat Who Composed, illustrated—as Gittel is—by Amy June Bates, about composer Moshe Cotel’s fluffy musical colleague. She’s won National Endowment for the Arts fellowships, Sydney Taylor Awards, Stonewall Honors, a James Baldwin Award for Cultural Achievement, and perhaps most importantly, the Cat Writer’s Association Litter-ary Award.

“As a child, I couldn’t articulate the need I had to see myself reflected back to me in books or films or TV,” she told me. “Then when I was in my 20s I saw The Carp in the Bathtub in a bookstore. And tears came to my eyes. It was about a family like mine! I was so moved by it. And that taught me something about the direct experience of how important it is to see yourself in a book.” Such a mashup of food and Jewishness and familial love is perhaps strongest in Newman’s A Sweet Passover, illustrated by David Slonim, about a grandpa making a little girl his special matzo brei. “That’s my father,” Newman said. “He was still alive when it came out, and he was so excited that I put his recipe in the book. There was nothing special about it—it was the most basic recipe and he cooked it once a year, the Sunday of Pesach. But he’d look at the book and say, ‘here’s my recipe!’ and he was so proud.”

Heather, though, was where Newman’s journey in children’s literature began. In 1988, a young lesbian mom in Northampton, Massachusetts, where Newman lived, told her how much she wanted children like hers to see themselves in literature. “I knew how those kids felt,” Newman recalled to Publishers Weekly. “When I grew up in the 1950s there were no books about a Jewish girl eating matzo ball soup with her bubbe on Shabbat. I definitely felt like an outsider. It struck a chord with me.” Newman’s friend Tzivia Gover ran a desktop publishing company called In Other Words; the duo “stuffed envelopes and licked stamps and begged for $10 donations to raise $4,000 to publish a book about a little girl with two moms,” Newman told me. It came out in December 1989. It wasn’t the first picture book about a kid with lesbian moms, but it was the first happy one.

“Representation matters,” Rabbi Rachel Weiss, a lesbian rabbi and mom of two kids, ages 5 and 10, told Tablet. “I first read Heather in 1996, as a college student, when I brought Lesléa to speak on campus and she gifted me and my then-girlfriend—now wife!—with a copy of the book. Since then, reproductive technologies have changed, gender expressions and diversities have only expanded, and those are good things … but the reality is that the number of children’s books that we as a two-mom family can turn to with our children to show them reflections that look like them is sparse. Heather Has Two Mommies was the first to show families that look like mine, and I am always grateful to stand on the shoulders of those who pushed to put our families in the public eye and continue to inspire others.”

Heather went out of print in around 2012. But Candlewick Press brought it back, with lively new illustrations by Laura Cornell, in time for its 25th anniversary. “I’m fond of the old art,” Newman said. “It’s such a part of me. But I knew it looked kind of dated. We couldn’t afford full-color illustrations then. Some kids thought it was a coloring book! It was fine with me if they colored it in. But it needed new art, and I love the new art. I love Heather’s purple cowboy boots.”

“I also rewrote it,” Newman added. “There was a line about how at story time, when Heather wondered if she was the only kid without a daddy, ‘Heather’s forehead crinkled up and she began to cry.’ I took it out. She’s a happy kid from a happy family! And when all the kids draw pictures of their families, I added a kid being raised by a grandparent. That’s not uncommon; I wanted it in there. And I tightened up the text a bit. I hope that in 25 years I’ve learned something about the craft of writing.”

“With every book I write,” Newman continued, “I want to tell the reader, ‘you matter, and you belong.’” Which led to the question: Do Jews belong—or rather, are they embraced—in the movement to increase diversity in children’s books? She paused for a long moment. “It’s puzzling to me,” she said. “I feel sad. I wonder why Jews are left out … except that we’re always left out?”

Newman offered an anecdote. “Maybe 20 years ago at a workshop there was a warmup exercise: ‘If you like strawberry ice cream go to that side of the room! If you like pistachio go to this side of the room!’ Things like that. And then it was, ‘If you’re a person of color go to that side of the room, and if you’re white go to this side!’ And a bunch of people congregated in the middle, saying, ‘We’re the Jews!’ We didn’t plan it. We didn’t talk to each other. We just knew we didn’t belong anywhere except together. It still feels that way.”

Of course, LGBT children’s books aren’t universally embraced either, even 30 years after Heather’s debut. Last month, a guy brought a gun to Drag Queen Story Hour at a Houston library. In October, a man checked several LGBT-themed children’s books and YA novels out of an Iowa library and publicly burned them, along with a toddler-size orange dress to represent Morris Micklewhite and the Tangerine Dress. “A dress is a piece of cloth,” Newman said with a sigh. “It doesn’t have a gender. If a boy or girl or a child who doesn’t identify in binary terms wants to put on a piece of clothing, why is that so threatening?” She added dryly, “I read thousands of books about heterosexual people when I was a child, and none of them kept me from growing up to be a lesbian.”

Next year, Newman will welcome a new book called Welcoming Elijah: A Passover Tale With a Tail. “It involves a cat, and that’s all I’ll say,” she said. Then she amended: “It takes place at a Seder with a lot of grown-ups and a lot of kids. I didn’t use the word mother or father anywhere in the book, and you can look at the pictures and create any kind of family constellation you want. At a Seder everyone is welcome. That’s important. It’s important to welcome the stranger.”

Which brings us back to Gittel’s Journey, a book about a whole country welcoming a very small stranger. “When my grandparents came over, there were whole societies set up to welcome immigrants and provide services and make them feel at home, with language classes and night school,” Newman said. “Not that those things don’t exist now … but the other things going on, in terms of breaking up families and snatching people and photos of kids in cages—it’s infuriating. It’s a hard time for anyone who has a heart, but especially for anyone who has a similar history. I had my grandmother until I was 33 years old. That’s my history. And what I can do is write a book that will hopefully get people of all ages talking about how important it is to be compassionate and welcoming.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.