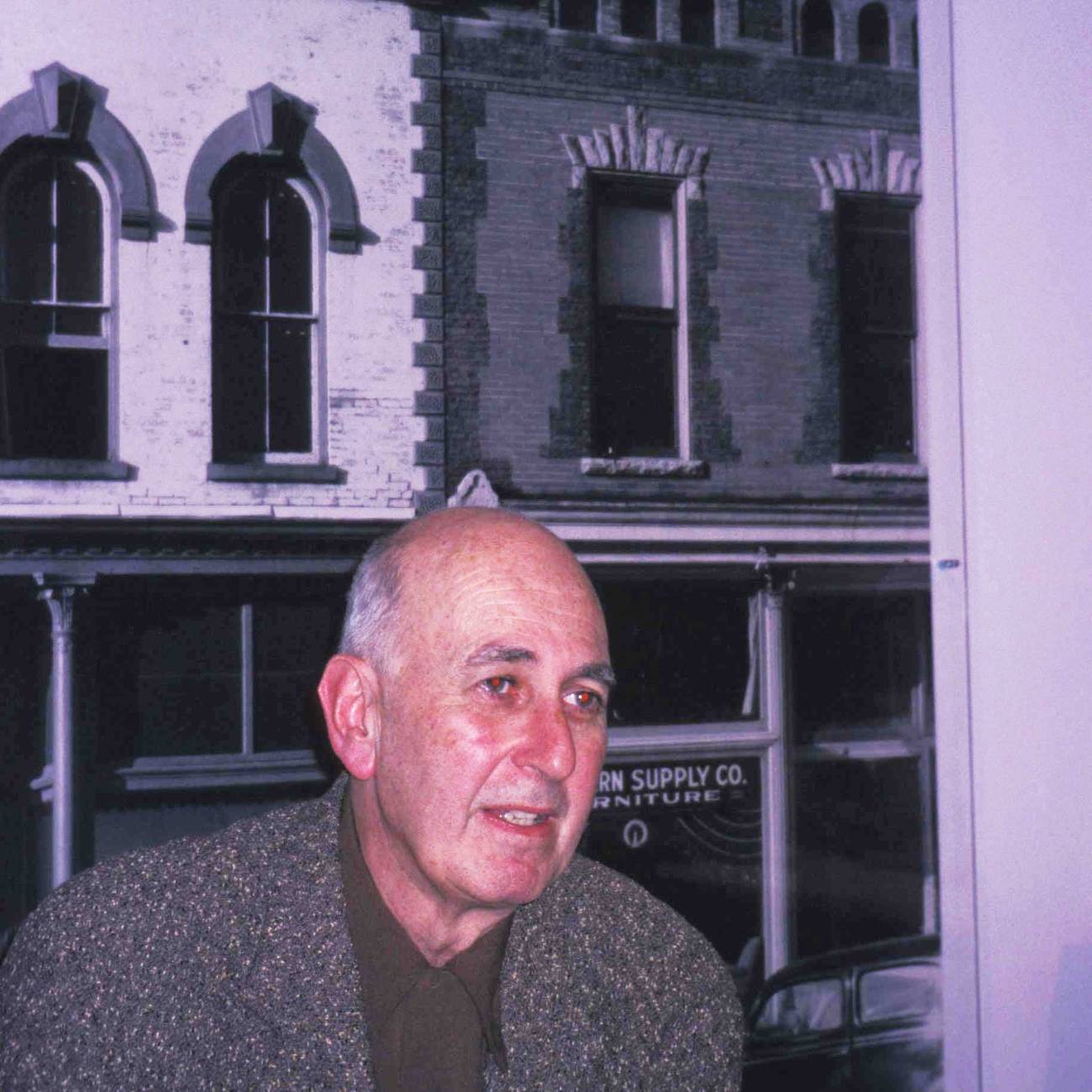

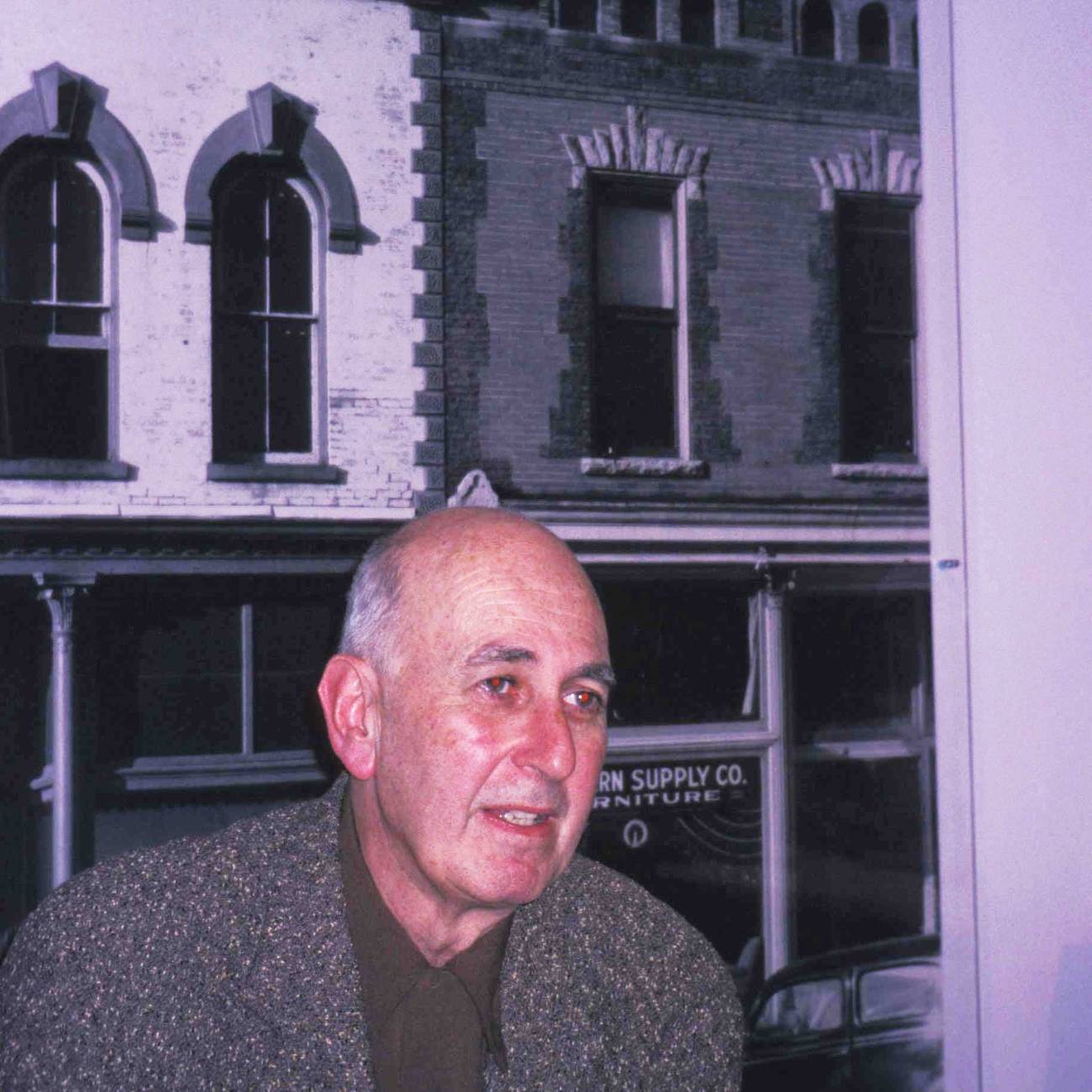

The Dark Angel of Nonfiction

After his retirement from Columbia, Phillip Lopate prepares for more books—and possibly more teaching

“I was faced with a decision: either to accept a demotion to an adjunct professor, or to retire. And I chose retirement, which is a very scary thing,” Phillip Lopate recently told the crowd in a heartfelt speech at the party celebrating his retirement from Columbia University.

Expecting to hear the usual superficial sentiments, I was shocked. I nervously scanned the room at Faculty House, filled with the acclaimed 79-year-old author’s luminary colleagues (like Lis Harris, Benjamin Taylor, Margo Jefferson, Leslie Jamison, Sam Lipsyte, Alan Ziegler, and Bill Zavatsky.) Nobody batted a literary eyelash—in fact, they laughed.

I shouldn’t have been surprised by Lopate’s candor. After all, the author of 20 books became famous as a first-personal essayist sharing raw and revealing prose, elevating short nonfiction pieces from what Morris Dickstein called a “stepchild of serious literature” to an important art form. And I’d been quoting his theory that “the problem with confessional writing in this country is that people don’t confess enough” to my writing students for decades.

Still, it was an emotional departure, since Lopate first came to Columbia in 1960 as a 16-year-old student getting his B.A. in English. “My mother, an actress, turned on the waterworks to get me a full scholarship,” he told me over the phone the next day, reminiscing about his 63-year connection to the institution that shaped his illustrious career—a career that launched a whole new genre.

“Although Jews had been excluded from the Ivy League, Columbia admissions director David A. Dudley chose my class of 1964 based only on grades and test scores. They called it ‘Dudley’s Folly’ because there were so many Jewish New Yorkers my year,” Lopate recalled. “They decided never to do it again—and fired him.”

Making the most of college, Lopate edited the Columbia Review, founded film and jazz clubs, and worked at Ferris Booth Hall, ensuring students wore the expected jackets and ties. He idolized critic Lionel Trilling, the first Jewish professor in the English department. But studying at Columbia was a culture shock, and Lopate felt looked down on. “I’m from the slums of Brooklyn. Some of the gentlemen professors were snobbish,” he admitted. “There was class tension.”

It wasn’t easy growing up as one of four kids of his well-read, depressed, and sometimes suicidal factory-worker father Albert and narcissistic mother Frances, a candy-store owner who launched into show business at 50. Their dramatic family saga is laid bare in his poignant memoir A Mother’s Tale and intimate, darkly hilarious essay collections Bachelorhood, Against Joie de Vivre, Portrait of My Body, and Portrait Inside My Head, where he brilliantly divulges his mother’s serial infidelities and father’s physical abuse, as well as his own graphic sexual exploits and therapy.

In his essay “Willy,” he’s sitting on the bed with his mother—who’s wearing a black nylon slip—as she confides to the 8-year-old author about the unhappiness that led to her affairs:

Whenever I found myself … listening to someone (usually a woman) in torment … my mind has gone back to Mother in her black slip. When I was in the mood to rebel against her personality, I would reproach my mother for taking away my childhood by placing me in the position of her judge and pardoner, and by telling me things that perhaps were not suited to my age. But what’s the point of blaming, when it is questionable who seduced whom? She needed someone to talk to, and I would have sold out my “golden childhood” a dozen times over for a compliment like the one I received. She said, “You know, I keep forgetting that I’m talking to an eight-year-old. It’s as if I were speaking to someone older and wiser. You’ve made me feel a lot better.”

I blushed. I had a found a new way to make my mother love me.

Perhaps Lopate’s early difficulties led to his later compassion.

“Phillip is a big mensch, one of the most generous, thoughtful people I’ve ever known. He’s a giver. We’ve been close for over 50 years. I love him deeply,” said poet and translator Bill Zavatsky, a fellow Columbia alum. (I agreed with his assessment. Since my shrink warned I was too nice and had to be more “ruthless” to find success, I was stunned that someone as distinguished as Lopate took time to endorse one of my memoirs, write a job recommendation, and do literary events with me.)

Zavatsky was working at a bookstore when he first encountered Lopate, who was on the way to an anti-Vietnam War protest that got him thrown in jail. “We jumped to each other’s vibe,” Zavatsky said.

Lopate helped him get an early teaching job. When Lopate’s publishing deal for a book of poems fell through, Zavatsky, editor-in-chief of SUN Magazine and ready to start SUN press, offered to put out Lopate’s first poetry collection himself, photocopying it at a Brooklyn copy shop.

“I published so many Jewish poets that our mutual friend Harvey Shapiro called me the ‘Shabbos goy,’” Zavatsky remembered. “At a poetry reading at West End Bar, a drunken Irish Catholic guy heard Phillip read a self-revelatory poem and cried out, ‘These Jews have no shame!’ We all cracked up, the guy was carried out of the bar and Phillip went ahead with the reading.”

Lopate was broke and desperate for a job when Kenneth Koch recommended he teach at Bedford Lincoln Muse, a community arts center in Brooklyn. Then Herbert Kohl led him to Teachers and Writers Collaborative, where Lopate was “a progressive radical disrupting the education system.” His 1975 book Being with Children: A High-Spirited Account of Teaching, Writing, Theatre and Videotape chronicled teaching poetry in an urban school. In The New York Times Book Review, Vivian Gornick said the “wise and tender portrait of a small society” was “funny, touching and alive,” sparking their lifelong friendship.

Teaching at Cooper Union and Fordham was very “fly-by-night,” he said, with poetry and fiction in the foreground: “I was the dark angel of nonfiction, pushing my way into the curriculum.” His first job in “a fancy creative writing program” was from 1981-89 at the University of Houston, whose faculty boasted Stanley Plumley, Edward Hirsch, Richard Howard, Donald Barthelme, Robert Cohen, and Ntozake Shange.

“I enjoyed it there,” Lopate said. “But people in Texas used to tell me, ‘You remind me of Woody Allen,’ because that was the only New York Jew they knew.”

Yet why was the protagonist of his first well-received 1987 novel The Rug Merchant a middle-aged Zoroastrian in Manhattan who was from Iran?

“As a kid, I was an Orthodox atheist,” Lopate told me. Frequenting only frum synagogues in Williamsburg, he’d joined a Hebrew choir and considered being a cantor. While soon entranced with Philip Roth, Saul Bellow, Norman Mailer, Bernard Malamud, and Primo Levi, Lopate said he “feared they had the territory all sewn up. So I focused on international literature.” Eventually he couldn’t help “pillaging the magic barrel” of Jewish humor, he said, unable to “fight my lineage.”

Indeed, he even joined a weekly Genesis group with Rabbi Burt Visotsky, authors Max Apple, Cynthia Ozick, Harvey Shapiro, “and scholars who knew Hebrew traditions better than the writers.”

He finished his Ph.D. at Union Graduate School. Along with delving into his own traumas, he became “an amateur scholar, a library rat endlessly curious and investigating and nibbling at different subjects,” with sub-specialties in film, architecture, urbanism, literature, and the essay itself. Among his opus is the popular craft book To Show and To Tell, and bestselling anthologies The Art of the Personal Essay, Writing New York, and The Contemporary American Essay, which is used in many writing classrooms, including mine.

“Initially, for my literary nonfiction courses, I had to photocopy different essays for my students to read,” he told me. “There were no good anthologies to teach from. I had to make them myself.”

In 1989, when Lopate returned to New York, Robert Towers hired him as an adjunct at Columbia. He became a professor there and in 2008, the director of their graduate writing program’s nonfiction concentration, where he hired me to teach. His students seemed to adore him and found studying with him unforgettable.

“He just introduces you to totally different time periods, worlds, depths of knowledge. He hasn’t read five Montaigne essays, he’s read them all. Besides being energetic, curious, and well-read, he wears it lightly,” said the award-winning novelist Rivka Galchen, a New Yorker staff writer who took his class in 2005. “Most writers are melancholic. He’s joyful, with infectious energy. He helped me grow intellectually. He’s beloved and special. There’s no replacement Phillip Lopate.”

That hasn’t changed, according to current student Sarah Swinwood: “Having him as my thesis adviser was such a gift. He thoroughly went over every word I wrote, offering insight in a direct, clear, honest way, helping me believe in myself and enhance my work. He’s a model for what a writing professor should be.”

His peers appear to agree.

“Phillip and I taught a seminar together twice. We had a fine old time, conversing with each other and our students. I enjoyed watching him with the class: He’d speculate, analyze, question, and urge them to question right back,” Columbia professor and Pulitzer Prize-winner Margo Jefferson told the crowd at his party. “Once, when he was teaching Diderot on painting and acting, he told them, ‘You’ll enjoy these. He’s brilliant and he’s a scamp.’ So is Phillip.”

While Lopate has been honored by the Academy of Arts and Letters, Guggenheim Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Arts, he was hurt that Columbia didn’t continue his contract.

“It might be a financial decision,” he conceded. “They seem to be on a mission to get rid of older professors making good salaries. I think it’s cheaper to hire young, up-and-coming writers. My mistake was leaving Hofstra, where I had tenure, for a contract at Columbia. I assumed it wouldn’t be a problem to keep renewing it. But they chose not to.”

He’ll continue writing from his Carroll Gardens brownstone in Brooklyn, where he lives with his second wife of 32 years, Cheryl Cipriani, a graphic designer and creator of several of his book jackets. His daughter Lily—who had her bat mitzvah at Kane Street synagogue—is now a 28-year-old writer and editor. “Where did she get that from?” he joked.

“When I was a trembling freshman, I had two modes in my head,” Lopate told the university paper. “One was to become a great writer like Dostoevsky and the other was to be an utter failure. I didn’t imagine being a successful ‘minor writer.’ I have my place in the culture, not a huge place, but it’s respectable.”

He’s not resting on his laurels, with two new books: A Year and a Day, an essay collection, will be published by The New York Review of Books in the fall. And ironically, his first book with Columbia University Press, My Affair with World Cinema, comes out after he leaves his alma mater, where he’s taught off and on for 34 years.

Not that he’s ruling out another university gig. “Being back at Columbia was the highlight of my academic career,” Lopate said. “About to turn 80, little did I know I still had some life in me … and some more teaching.”

Susan Shapiro, a Manhattan writing professor, is author of several books her family hates like Barbie: Sixty Years of Inspiration, Five Men Who Broke My Heart, The Forgiveness Tour, and her writing guide, The Book Bible. Follow her on Twitter at @Susanshapironet and Instagram at @profsue123.