The Fluffy Bunnies of Auschwitz

Heinrich Himmler oversaw breeding centers for Angora rabbits in dozens of concentration camps. While people were imprisoned, tortured, and murdered nearby, the prized animals were kept in luxury.

Heinrich Himmler is best remembered as the mastermind behind the Final Solution and its web of concentration camps, where millions of Jews and other prisoners were imprisoned and murdered during WWII. But as Reichsführer of the SS, Himmler also spearheaded another, quite different concentration camp project—one that demonstrated all too clearly whose life had value in the eyes of the Nazis, and whose did not.

As the Nazis pushed east into Russia in 1941, the German troops needed warm clothing. So Himmler launched Project Angora.

Ever fashion conscious, the Nazis were aware of Angora’s glamorous place in Hollywood and high fashion. Just as the SS uniforms were designed to inspire fear in their victims and give their wearers sex appeal, the German forces would be outfitted for battle in chic finery with warm, fluffy Angora. To generate this luxurious fiber, Himmler, a fanatical believer in the power of agriculture, established Angora rabbit-breeding centers at 31 death and concentration camps including Dachau, Buchenwald, Theresienstadt, and Auschwitz. Silky rabbits were raised in luxurious heated accommodations, in stark contrast to the conditions facing the human prisoners. Holocaust scholar Harold Marcuse has said that prisoners could be shot for mishandling a rabbit and that some prisoners at Dachau were killed after a rabbit was stolen and eaten.

The bunnies were prized for their fur—used to line the jackets of the Luftwaffe pilots—and for their wool, which was turned into turtleneck sweaters knitted for pilots, socks to keep cold feet warm on submarines or U-boats, and long underwear for army soldiers. (Wool is collected by shearing or brushing the animals, and is then cleaned and spun into yarn; fur requires skinning the animal.) American soldier Jack DeWitt, who was among those who liberated Dachau, took one of the “nice warm bunny jackets,” he said in a 2007 Wisconsin Public Radio interview.

Little would be known about the Angora-farming operation if not for a curious 15-by-13-inch “brag book” that belonged to Himmler. The book—which is currently in the archives of the Wisconsin Historical Society—is a photo-rich testimony to Himmler’s efforts to create a new world order with German farmers at its center. The cover is woven from luxurious Angora, which still sheds the rabbits’ long hollow fibers when touched. It’s off-white with a woven SS “seal” on the cover and the word “ANGORA” in all caps.

Journalist Sigrid Schultz, who traveled with the American First Army in the winter of 1944-45, found the book in a barn on the grounds of Himmler’s lakefront alpine villa in Tegernsee after she pursued a lead from a trusted source, according to her personal records. Schultz reported the volume was one of Himmler’s most prized books, “one of two books that had been lying on a the table in a small library for months” along with “a first edition of Mein Kampf, dedicated to Himmler, with annotations … added by Hitler himself,” according to Fredericka (“Rieke”) Richter, the on-premises doctor who treated Himmler’s wife and children, per Schultz’s notes.

The album’s images include idyllic scenes of rugged men, their button-down shirts’ sleeves rolled up, laboring to build an expanse of rabbit hutches to ensure that their fluffy friends would have ample space; hutches were sanitized or deloused, keeping the prized coats clean. The oversize Angora-covered book also contains photos of smiling, well-heeled workers in lab coats lovingly caring for the pristine white animals. Newborn bunnies were photographed in their first days of life and shown huddled in a nest lined with Angora fur.

Once the rabbit fur was collected, men in white lab coats cleaned their wool in pristine stainless steel vats. The fiber was loaded into tall brown bags and stored before it was transported to Berlin; a photo in the album shows a uniformed young man loading the giant bags of wool into all-too-familiar train cars.

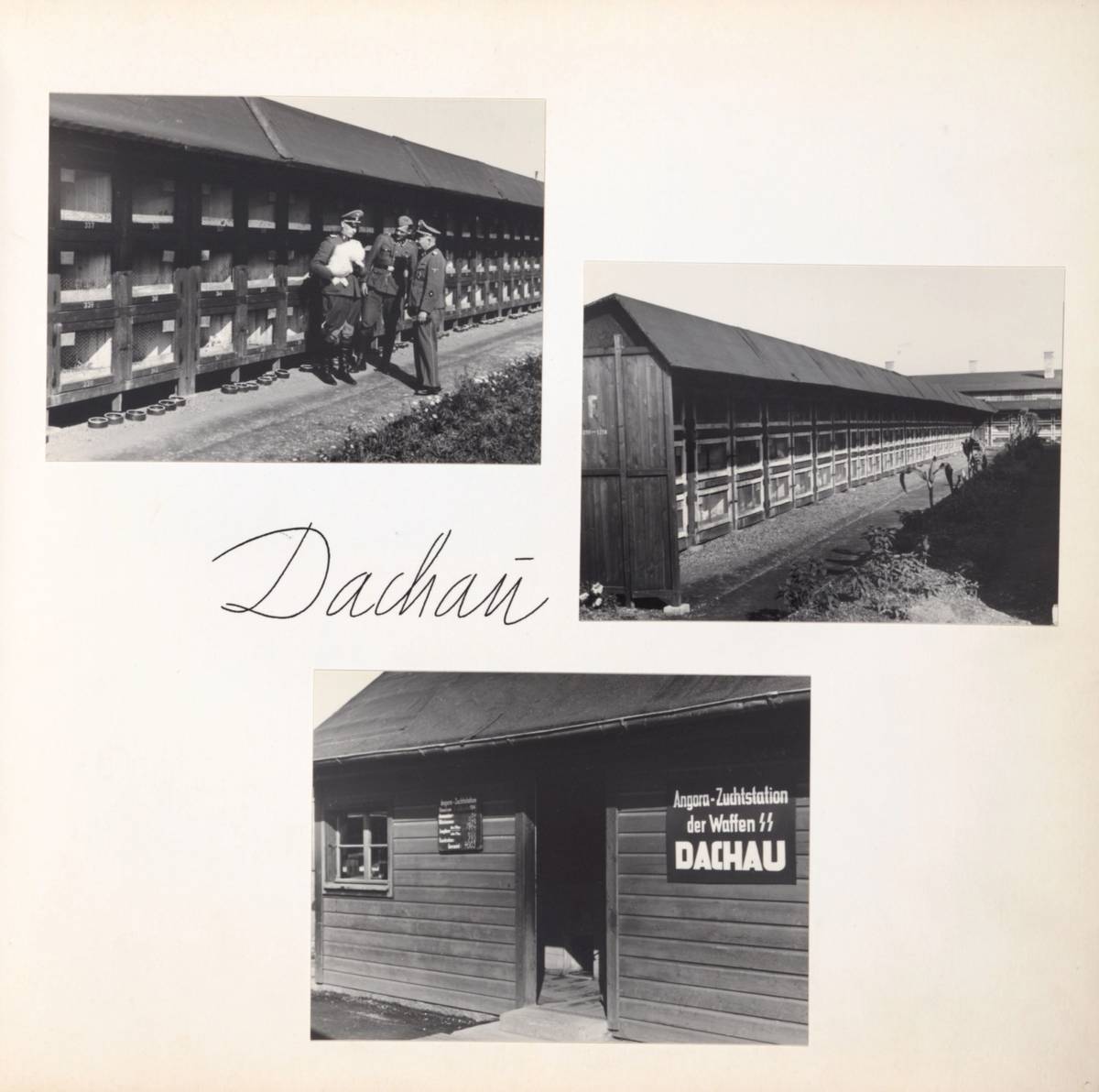

The book features images from several camps that were part of the project, with pages showing their Angora breeding facilities. The page for Dachau includes a chilling photo of an unnamed SS officer holding a fluffy bunny on his hip as he talks with two others in uniform in front of the sprawling hutches.

The book covers the period from 1941-43 and shows the rabbit population expanding from 6,500 to 25,000. This period overlaps with Operation Reinhard, the Nazi program to exterminate Jews from Nazi-occupied Poland at a rapid pace at three main killing centers: Sobibor, Belzec, and Treblinka. Himmler, an agricultural zealot, sought the “reconstruction of the Germanic heritage in the widest and most comprehensive sense,” meaning a return to a medieval Germanic ideology, a non-Christian divine order. This new morality would allow him to reject the values of Christian mercy, while ruthlessly pursuing the eastward expansion needed to create Lebensraum, or “living space.” It would also allow him to destroy so-called subhuman groups including communists, Slavs, and Jews, among others, ultimately forming a new ruling class of farmers, the SS, who would “see to it that only people of purely Germanic blood live in the East,” said Himmler, who imagined Germany as “the sole decisive power in Europe,” according to the Nazi Conspiration Aggression compiled by the American and British governments in preparation for the Nuremburg trials.

The Angora rabbits, like the SS, were emblems of Himmler’s vision of Nazi superiority: a pure race bred through German agricultural excellence. The breeding centers are likely to have played a role in the propagation of massive German Angora rabbits, the largest of the Angora breeds today.

As the end of the war drew near, Richter noted, Himmler wanted to remove the “animal book” from the house. The reason is clear: The book was a prized science-fair diorama of sorts, showing the power of German racial engineering to breed pure stock, a master race of rabbits, an embodiment of his Germanic orthodoxy and something that “would repel every foreigner who had seen concentration camps” and could make them “aware of the real role Himmler’s SS played in WWII,” writes Schultz.

Schultz’s notes about Himmler’s book were compiled by the Wisconsin Historical Society, which also houses her archives. She wrote: “In the same compound where 800 human beings would be packed into barracks that were barely adequate for 200, the rabbits lived in luxury in their own elegant hutches. In Buchenwald, where tens of thousands of human beings starved to death, rabbits enjoyed beautifully prepared meals. The SS men who whipped, tortured, and killed prisoners saw to it that the rabbits enjoyed loving care.”

The juxtaposition the Angora book’s map of breeding centers with the Holocaust museum-style wall maps showing the locations of camps and their death tolls is, at first look, a study in cognitive dissonance. If one didn’t know of the mass murder and forced labor at those places named on the map, they might see the Nazis as a fastidious and nurturing group who provided rabbits as pet therapy for their troops.

At the infamous death camp Sobibor, the Nazis established a knitting barrack called the Strickstube, where prisoners were forced to harvest scraps of used wool from the clothing taken from those who’d been killed and create new garments for the Germans. Sobibor survivor Regina Zielinski recounted her experience in a U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum interview before she died in 2014. But Himmler’s Angora breeding centers seemed to operate in a different way: The rabbits’ luxurious wool and fur were, for the most part, collected and shipped elsewhere for processing. But even if the official system kept the carefully tended animals away from the horrible human conditions inside the camps, some informal arrangements may have been made.

Today, a growing group of women connect their own Holocaust remembrance to the knitting projects in the concentration camps. Helena Weinrauch, a survivor of three camps, the death march, and torture by the SS, wears a bright blue Angora sweater to a Passover Seder every year—and has for more than 70 years. The sweater was knit after the war by Weinrauch’s friend Ann Rothman, who stayed alive by knitting for Nazi wives while a prisoner in the Lodz Ghetto.

Rothman was, as Weinrauch tells it, “so good at knitting that she knitted coats for the wives of the German people” and “it became known that Ann can knit skirts, a blouse—anything you want she can knit it.” The sweater is bold, metallic, and its voluminous sleeves have a fuzzy Angora halo. It’s every bit as glamorous as one Lana Turner would wear. Weinrauch calls it her “Passover sweater.” The fiber that once stood for luxury now serves as a ritual object, an essential part of her Passover observance, cloaking her in a fabric once reserved for free people. When Rothman gave the sweater to Weinrauch she asked her to “wear it to remember them,” referring to those both women lost.

I read about Helena’s sweater in Moment magazine and couldn’t get it out of my mind. In February 2022, I hired the young Jewish knitwear designer Alix Kramer and together we published a sweater pattern inspired by Weinrauch’s story. Other knitters of all ages are crafting their own blue Passover sweaters as “a way to connect the past with the present, and the future,” said Judy Ehrenstein of Silver Spring, Maryland. The experience of knitting the sweater creates feelings of continuity and “connection with our survival as a Jewish people in both biblical times and in recent times,” said Sara Kober of Scarsdale, New York.

The Passover sweater is not the only object that has united communities of knitters. In 2003, Lea Stern saw a green child’s sweater at the Hidden Children exhibit at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. Years later, Stern reverse-engineered the sweater so that knitters could replicate the one worn by Krystyna Chiger Keren when she was a small girl hiding in the sewers of Lvov, Poland—now Lviv, Ukraine. Stern launched the Green Sweater Project and knitters responded. This comes as no surprise to Jodi Eichler-Levine, Berman Professor of Jewish Civilization at Lehigh University, who notes that “these crafters are engaged in honoring and nurturing the fortitude, memory, and community of the Jewish people.” The knitters of Nazi-controlled Europe did not have a choice—they had to craft to survive. Now, these sweaters bring others the chance to knit their own tributes to freedom and survival.

Tanya Singer is the general manager of Tablet Studios and a co-host of Beautifully Jewish.