Marvin Schick, 1934–2020

A pioneer of Jewish education, and the larger communal health he believed it fostered

Dr. Marvin Schick, a pioneering Jewish communal activist, died last night. The cause was a heart attack, suffered at his home in Borough Park. He was regarded by many as the Jewish communal curmudgeon par excellence, though at times this obscured the real truth, which is that Schick deeply loved the Jewish people, even (or especially) those with whom he fundamentally disagreed.

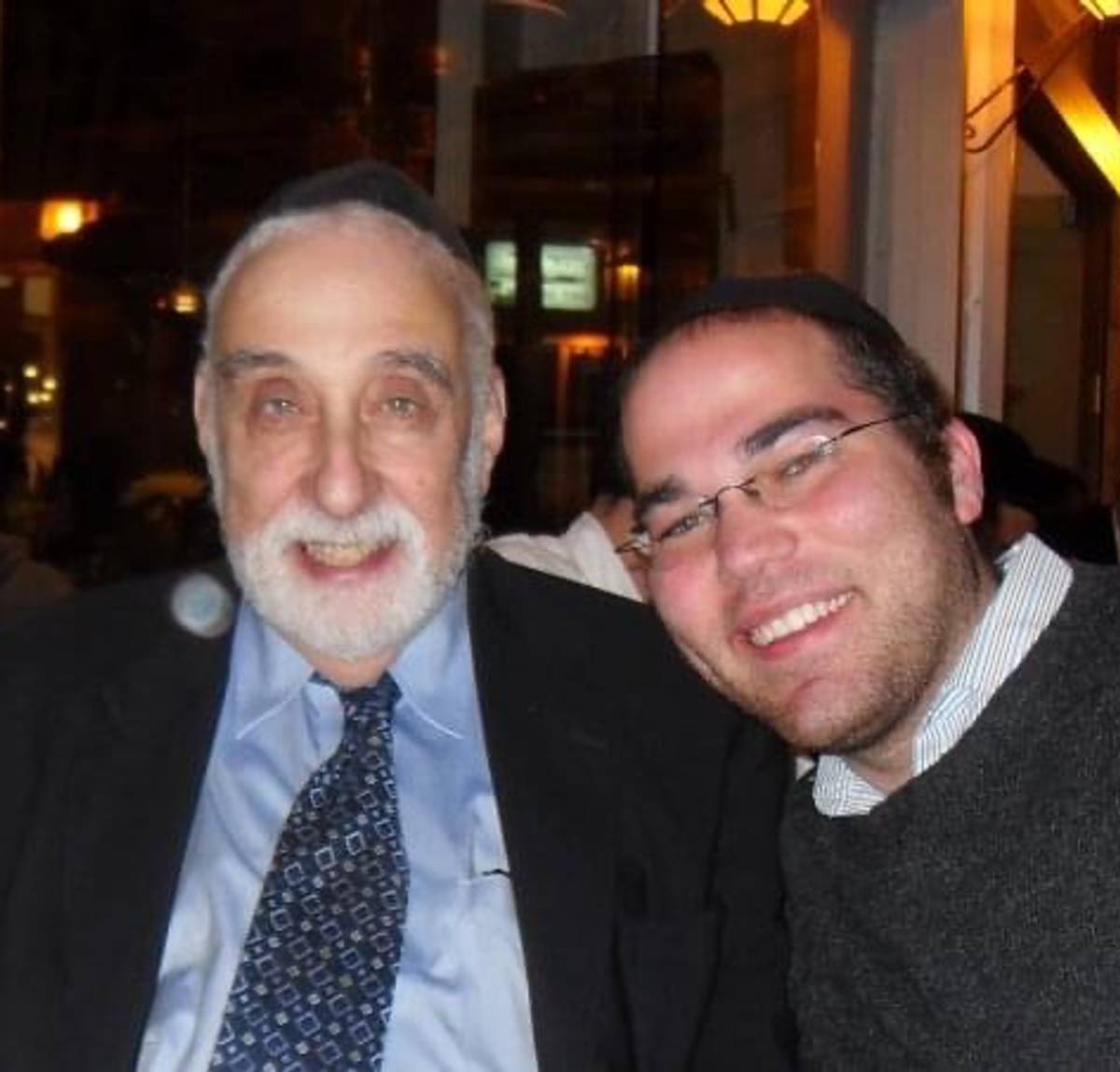

In addition to his public work, for more than 15 years Dr. Schick was also my mentor, then my friend—and soon a man I adoringly called “Uncle Marvin.” He was always available to answer any question by phone or email, and not infrequently dished out criticisms—always with love, always brutally honest. He often told me that his mission in life was to help others, and to think of the unity of the religious community, and not to focus on the internal boxes of the religious community that otherwise divide us—“even if these boxes have validity for sociological study, they don’t have validity in the real life.” He pushed me to break away from the categories arbitrarily established by others. “It’s not easy to be iconoclastic,” he would say.

He was a lifelong resident of Borough Park and loved its every street, shtiebel, and store. He was a collector of rare seforim and a dozen years ago proudly told me of his dream to own an entire set of the Bomberg Shas, which he would purchase volume by volume at auction. The last time we spoke about it, he noted that he had 31 out of 45 of the volumes.

Marvin was fond of saying that he was born 15 minutes before his twin brother, Allen, on July 3, 1934. Their Romanian immigrant father, Rabbi Dr. Joseph Schick, served as the rabbi of the West Side Jewish Center on West 34th Street (between 8th and 9th avenues in Manhattan), and died on Purim in 1938—which fell on St. Patrick’s Day that year. Marvin and Allen were just 3 years old. Their mother, Rebbetzin Renee Schick, was widowed and without any relatives to assist in raising the children. When his mother died in 1998, Marvin wrote, in a moving obituary for her, of the trauma of his early childhood spent living in an orphanage and attending public school:

My father had died penniless; three weeks later she was served with eviction papers. She had no close relatives in this country, no parents or siblings or nieces and nephews, only cousins and four young children, ages 3 to 7. Allen and I were placed in an orphans’ home. In 1939, I was hospitalized critically ill with diphtheria. The next year was Allen’s turn with pneumonia. She turned to people for help and some of the responses added to her pain. A handful of people who assisted in a modest way could not forget to remind her of what they had done. Already in 1938 she had written to a saintly relative in Europe, asking whether she could send Arthur and Ruth to be cared for back home and also for advice. He responded that there were darkening clouds in Europe and told of a widow who, faced with a similar situation a century earlier, had provided for her children by baking challahs for Shabbos. Late in the year she moved to Borough Park where there were cousins who helped. Out of a small oven in her apartment, she began to bake, four challahs at a time. Skilled in all ways with her hands, her challahs and cake quickly gained acceptance. In 1943, the year of Arthur’s bar mitzvah, the family was reunited and my mother opened what would become perhaps the most famous kosher bakery in the world.

At the age of 17, Marvin met and become a devoted disciple of Rav Aharon Kotler. For the next dozen years, he traveled with Rav Aharon to meetings and conferences and learned how to think and act like a Jewish leader. Uncle Marvin would tell me that Rav Aharon would regularly go to the beis medrash where the teenage Marvin was learning and he would pluck him out of the beis medrash, and that there was no question in his mind that Rav Aharon Kotler felt that a Marvin Schick outside of the beis medrash would mean less “bitul Torah” inside of the beis medrash.

Marvin earned his doctorate in political science from NYU, and taught very briefly at Yeshiva University in the early 1960s. Then for many years he taught at Hunter College, Lehman College, and the New School for Social Research, where he taught political science and constitutional law. He also worked as a lawyer in private practice and founded the National Jewish Commission on Law and Public Affairs (COLPA).

While still single in his early 20s, Marvin was given the task of fundraising thousands of dollars for the Chinuch Atzmai organization, an educational movement in Israel established by the Agudah, though independently run under the spiritual auspices of Rav Aharon in the United States. Chinuch Atzmai focused on providing an Orthodox Jewish education for children from secular or irreligious homes in Israel.

It was at this point that he realized the need to focus on providing a deep Jewish education, so that every possible Jewish child could maintain a strong connection with his or her faith and traditions. He served as the voluntary president of the Rabbi Jacob Joseph School system for nearly a half-century, responsible for the fundraising of a network of schools in Staten Island and New Jersey. (One of his proudest acts was that he wrote personal handwritten notes to each of the several thousand supporters of the Rabbi Jacob Joseph School each year before Rosh Hashanah.)

Indeed, Marvin became a lifelong believer of the importance of a strong Jewish educational system across every denomination—he was particularly pained when non-Orthodox schools shuttered—and served as an early and lone voice to philanthropists to place Jewish education high on the communal agenda. As senior adviser to the Avi Chai Foundation, he conducted many pathbreaking studies on Jewish education, and his innovative “Census of Jewish Day Schools in the United States” remains the best source of information about Jewish education over the past generation—available online.

Several years ago, I presented Marvin and his family with thousands of pages of his weekly newspaper columns from the late 1960s until the early 1990s, which I had come across during the course of my own research into this era. In these articles—many of which were published under the “In The City” column—Marvin would weigh in on every single issue that impacted the Jewish community, and during his years of service (1969-1973) in Mayor John V. Lindsay’s administration, these columns were seen as the official City Hall mouthpiece of outreach to the Jewish community.

After decades of writing his formal newspaper columns in The Jewish Press, The Jewish World, and The Jewish Week, Marvin’s final foray as a weekly columnist came in the form of his op-eds released as paid advertisements. For several years, he maintained a blog that served as an autobiography-in-process, of sorts, and where he would share his various ruminations on communal topics. Several months ago Marvin published an article in Tablet magazine that shed light onto an otherwise overlooked chapter in the history of Jewish education in New York, when the Board of Regents adopted a resolution that “private or parochial schools that operate with a program providing a session carried on in a foreign language during the forenoon, with only an afternoon session in English, be advised that such practice violates the compulsory education law.” For the first time ever, Marvin shared how the plan was thwarted, and if not, it “would have meant the end of yeshiva education in New York.”

In 2009, I was studying at Yeshiva University’s branch in Jerusalem, and I invited Marvin to deliver an evening lecture to my friends on his reflections on Jewish education in North America. It was an evening where he shared some of his most cherished stories of his own journey, and I regularly relisten to the talk and gain renewed inspiration.

At the end of the late-night conversation, Marvin shared with us a story about the teacher, Rabbi Nachman Mandel, who taught him and his brother when they switched into RJJ in fourth grade for secular studies, and placed in the first grade for Judaica studies with younger students. Marvin told us what it was like to run into his teacher more than a half-century later. After embracing each other, Marvin joked that he had a problem with a grade that he received in the first grade. Rabbi Mandel responded: “Mir ken dos m’saken zein”—it can be fixed. It was this phrase that Marvin described to us as a philosophy of Jewish education: that children and their education must never be discarded and that everything must be done to create a more lasting and sustained Jewish community. In Marvin’s earlier years of Jewish communal service, he was active in nearly every major and minor Orthodox Jewish organization—proudly being the only activist in both the (Haredi) Agudath Israel and the (modern Orthodox) Orthodox Union organizations during the 1960s and ’70s. Others saw it as a conflict; he saw it as a fusion and part of his individualistic personality. He established organizations that worked across communal boundaries and would fight for the individual Jew however they needed to be helped—regardless of ideological labels.

Later that trip, Marvin took me out of the beis medrash and we enjoyed a delicious dinner at Café Rimon—because, as he told me, “a Menachem Butler outside of the beis medrash would mean less ‘bitul Torah’ inside of the beis medrash.” I will cherish that moment for the rest of my life.

Menachem Butler, an associate editor at Tablet Magazine, is the program fellow for Jewish Law Projects at the Julis-Rabinowitz Program on Jewish and Israeli Law at the Harvard Law School, and a co-editor at the Seforim blog. Follow him on Twitter @MyShtender.