Next Year in Halifax

On Passover, celebrating our family’s arrival in Canada

My family’s Passover Seder is always dramatic. At the end of arami oveid avi, we don’t just recite the plagues—we act them out. Rubber frogs zing across the room, sticky dots on our faces represent boils, sunglasses for darkness. Then there’s everyone’s favorite: I flip on the ceiling fan switch and hundreds of pingpong balls, which I spent all afternoon piling onto paper plates taped to the fan blades, rain down as hail.

Our Haggadah has a social justice focus, too. We include an orange on our Seder plate to welcome LGBT+ people and anyone else who has ever felt excluded, for whatever reason. During Hallel, we invite in Elijah, but also Miriam. And to round out our inclusive table, we set out a paper cup for Alan Kurdi and other refugees and displaced persons, and uncork a bottle for Sylvia Rivera.

In terms of drama, Passover 2017 was no different. Still, the holiday was significant in two other ways: We said “hello” to a new Jewish adult in our family as we gathered with others for a combined second Seder and my younger son’s bar mitzvah at Shir Hadash, a Reconstructionist congregation in Milwaukee, and “goodbye” as well when I announced that my wife and I had sold our house and were leaving our jobs, pulling the kids out of school, and moving to Canada.

Now, nearly three years later, while COVID-19, a modern-day plague, ravages the world, the last few weeks of physical distancing at home has allowed me space and time to reflect on our journey, to consider why my family left the U.S., what we found here, and the parallels of our story with Passover.

When my wife and I got married in 2008, one of my conditions was that we would eventually have children. One of hers was that we’d raise them Jewish. Having explored various religions in the past, but never having found a spiritual home, I agreed. In 2012, we adopted our older son, Liam, when he was 9 years old; we adopted DJ four years later when he was also 9. Both were born into foster care, and initially it was a struggle to parent two children with symptoms of neglect and trauma. Added to this was the harassment and prejudice our family faced due to our menagerie of racial and ethnic, gender, and, of course, Jewish identities. My wife and I, both white, had been denied health care and lost jobs for being transgender. Now, I was scared for my black and brown children as they stepped out each day into a world of violence being directed at people of color, a fear reinforced by seemingly daily reports on the news of young men being shot dead by police and others.

Despite this, we found refuge at Shir Hadash. We joined when they hired Tiferet Berenbaum, a black, female rabbi, as a way to facilitate our African American son’s introduction to Judaism. As my family grew, so did our involvement in our Jewish community. I played drums with Shir Mishugas, our congregation’s music group. My wife served on the communications committee and redesigned the shul’s website. DJ volunteered as a peer leader to the younger kids during Yavneh, Rav Berenbaum’s Jewish education program. Liam happily joined other congregants, now close family friends, for Chinese food and a movie on “Jewish Christmas.”

My “burning bush” moment came on a warm spring day. My sons wanted to take advantage of the weather for their first-of-the-season bike ride, and my wife and I promised to pull their bikes out of storage after she and I ran a five-minute errand to a neighbor’s house. In the meantime, the boys busied themselves by playing basketball in the driveway. But upon our return, as my wife and I rounded the corner, a frantic man dashed down the sidewalk past us, throwing his full coffee cup in our next-door-neighbor’s lawn and pulling a phone from his pocket.

Concerned, I called out to him, “Hey, what’s going on?”

In part to me and in part to the 911 operator who’d answered his call, he replied, “I have the black man. The one the police are looking for. He’s breaking into a house.”

I joined in his pursuit, until, surprisingly, I realized he was chasing my sons up our driveway. Within seconds, this stranger had cornered my older son in our garage and was still barking into his phone that he’d caught the dark-skinned criminal breaking into our house.

“Wait! Stop!” I shouted at him. “That’s my son! He lives here!”

Undeterred, the man snapped back, “If he’s not a criminal, why was he running?”

Incidents like this seemed to be the new normal after the U.S. presidential election in 2016; the experiences of discrimination and marginalization we’d experienced beforehand were exacerbated in frequency and fervor. Bomb threats at our Jewish Community Center, vandalism at local Jewish cemeteries, and police presence required at High Holiday services were worrying. Living on the edge, as we did, in our misaligned and liminal, brown and black bodies, the incident brought us to an edge, and the sense of safety we felt at Shir Hadash came crashing down with emboldened strangers threatening my family’s existence. I had invested a lot in keeping my kids safe and happy. There was no way I was going to throw that all away by remaining in the U.S.

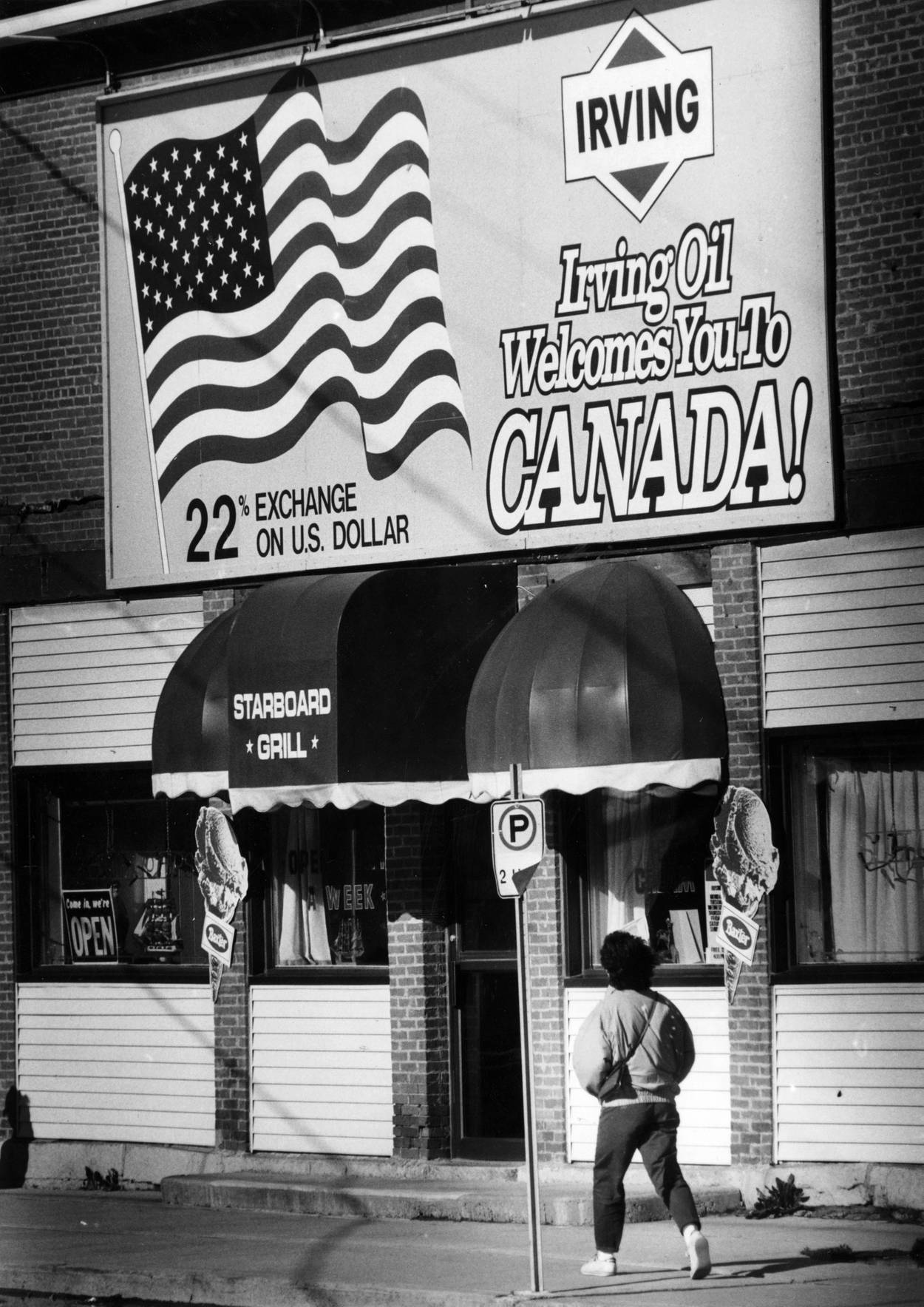

In spring 2017, after our final night in our now-empty house, we deflated our air mattresses, and assembled the kids in the car. We set off on our journey east, stopping in Buffalo, New York, and Amesbury, Massachusetts, to stay with friends and family along the way. On May 22, we crossed the border at St. Stephen into Canada. Like the ancient Israelites crossing the parted Red Sea to reach the Promised Land, the four of us boarded the ferry in our final leg of the journey, to cross the Bay of Fundy to land on the shores of Nova Scotia.

In the three years since, we’ve adjusted to our new schools, jobs, friends, and neighborhood. While Canada has its own struggles with racism, transphobia, and anti-Semitism, I no longer fear we will be denied medical treatment or become victims of gun violence. However, what we gained in safety and freedom, we lost in terms of Jewish community. There is no Shir Hadash of Halifax, the city we now call home. In fact, there are no Reform, much less Reconstructionist, shuls in the entire province. There are no Jewish day schools or JCCs. It’s next to impossible to find pomegranates on Rosh Hashanah or candles for Hanukkah. Nearly every Chinese restaurant is closed on Christmas Day.

Still, while sparse, opportunities for engagement with Judaism in Atlantic Canada are not altogether missing. The mezuzah attached to our front door has been a beacon for secular Jews, including neighbors, our real estate agent, and colleagues and classmates alike. In July 2019, it was standing room only at the Atlantic Jewish Council Halifax Pride Shabbat service, and after Hurricane Dorian slashed through Nova Scotia in September 2019, we joined other Haligonians, who flocked to the South End to one of the few grocery stores on the peninsula that had remained with power—and discovered its kosher section! And each year at Passover, friends new and old, Jewish and gentile, are invited to our table for Seder, including our friend from New York, who brings a separate suitcase packed with matzo in regular and gluten-free varieties. (The Canadian Border Services agents were puzzled by the term “matzo” and her telling of the story of Exodus, so she learned to simply describe them as big crackers.)

Since moving to Nova Scotia, we’ve also added to our own Passover traditions. Now, next to Elijah’s and Miriam’s glasses, Alan’s cup, and Sylvia’s bottle, we set out a glass for Canadian civil rights activist Viola Desmond, where we collect pennies (hard to come by in Canada!) to symbolize the injustice faced by people of color in our new country and elsewhere. We acknowledge Mi’kma’ki, the ancestral and unceded territory of the Mi’kmaq people, the land upon which our house sits from which we derive great and unearned benefit. From our table, we commit to using our newfound privileges to confront racism and sexism and ableism as it appears in front of our grateful immigrant eyes.

Passover 2020 has brought a real-life plague to the lives of people across the globe. But, unexpectedly, for our family, the coronavirus pandemic has brought even more opportunities our way to engage and, thankfully, derive comfort from Jewish community. We attended our first Shabbat service in years with Rabbi Elyse Goldstein at City Shul in Toronto via Zoom videoconferencing. The Atlantic Jewish Council is now advertising a slew of virtual offerings including Hebrew lessons, readings, and films. And we’re busy preparing for this year’s Seder by attending virtual classes on “making Pesach in the season of COVID-19.” Ironically, the pandemic that is separating us from each other, with provincial mandates limiting the number of people around our Passover table this year, has reignited what we had feared was a dwindling sense of connection to Judaism. Although we decidedly will not be acting out the plagues this year with our usual fervor in light of the current crisis, the four of us will still celebrate the freedom immigrating to Canada brought our family—not to mention, the gratitude that results when you do whatever it takes to keep loved ones safe.

If G-d had brought us out from the U.S.A., and had not led us to Canada – Dayenu.

If G-d had led us to Canada, and had not given us permanent residency – Dayenu.

If G-d had let us stay here permanently, and had not introduced us to welcoming neighbors – Dayenu.

If G-d had introduced us to new friends, and not reinvigorated our connection to Judaism – Dayenu.

Les Tyler Johnson is a teacher and writer living in Halifax, Nova Scotia.